Identifying Decisive Socio-Political Sustainability Barriers in the Supply Chain of Banking Sector in India: Causality Analysis Using ISM and MICMAC

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To determine the key barriers for socio-political sustainability in the supply chain of financial service firms

- To use ISM to establish the hierarchical structural model of the key barriers

- To classify the barriers on the basis of MICMAC results and to determine the most influencing barriers.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Evolvement of Socio-Political Sustainability

2.2. Socio-Political Sustainability in Supply Chain of Banks

3. Methodology

3.1. Identification and Determination of Barriers to Socio-Political Sustainability

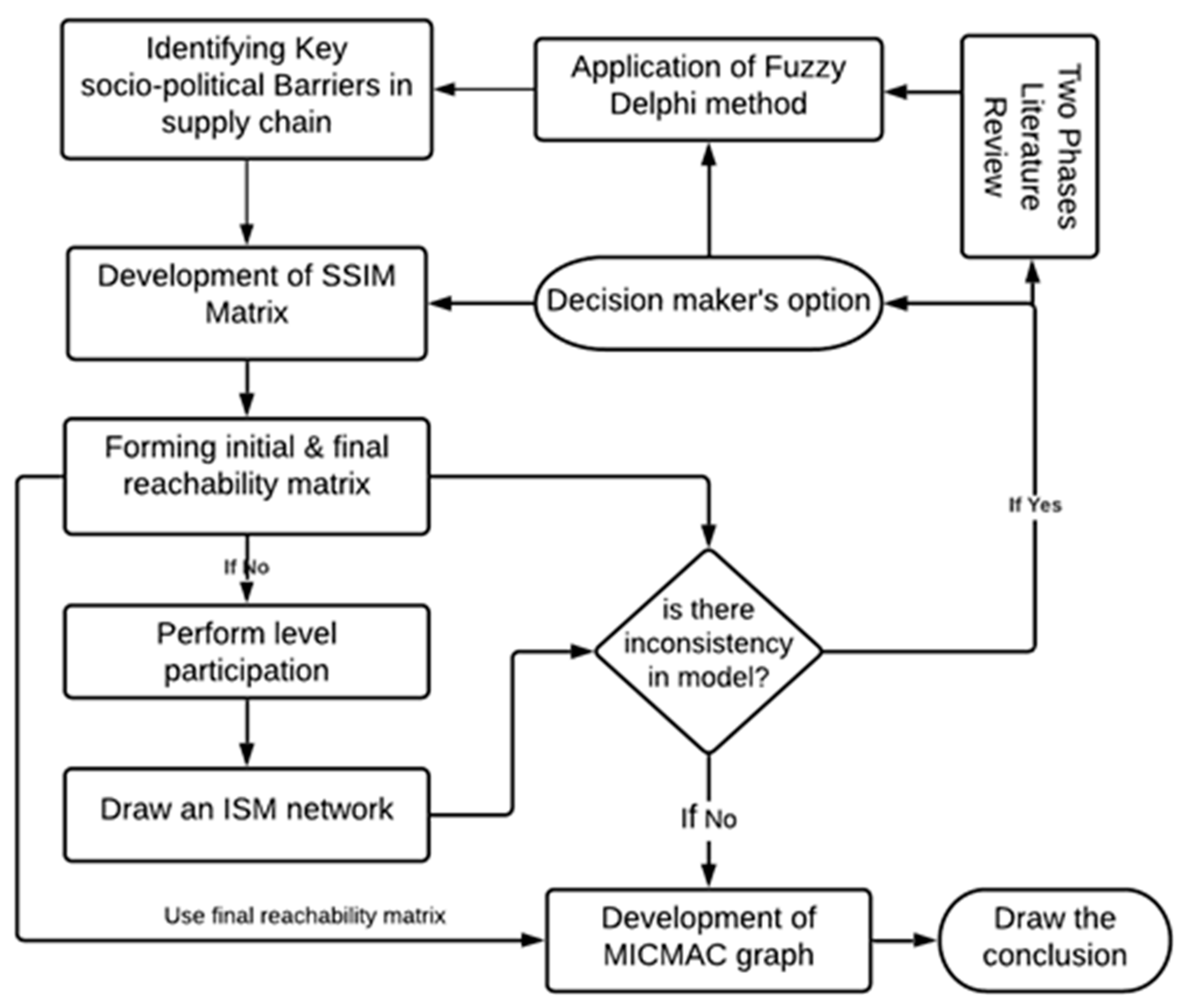

3.2. Adoption of FDM and ISM Approaches

3.2.1. FDM Approach and Results

3.2.2. ISM Approach

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Interpretive Structural Modelling

4.1.1. Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

- V barrier i influences barrier j;

- A barrier i is influenced by barrier j;

- X barrier i and j influence each other; and

- O barrier i and j are unrelated.

4.1.2. Development of the Initial Matrix and Final Matrix for Reachability

4.1.3. Level Partitions

4.2. Development and Results of ISM Structural Model

4.3. Results of MICMAC Analysis

4.4. Discussion of Results

4.4.1. ISM Analysis

4.4.2. Results of MICMAC Analysis

4.4.3. Managerial Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Barriers | Reachability Set R (Bi) | Antecedent Set A (Bi) | Intersection Set R (Bi) ∩ A (Bi) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1,B3,B4,B6,B7,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | ||

| B2 | B1,B2,B3,B4,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B3 | B3,B4 | B1,B2,B3,B4,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B3,B4 | I |

| B4 | B3,B4 | B1,B2,B3,B4,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B3,B4 | I |

| B5 | B1,B2,B3,B4,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B6 | B3,B4,B6 | B1,B2,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | ||

| B7 | B3,B4,B6,B7 | B1,B2,B5,B7,B8,B9 | ||

| B8 | B1,B3,B4,B6,B7,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | ||

| B9 | B1,B3,B4,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5,B9 |

| Barriers | Reachability Set R (Bi) | Antecedent Set A (Bi) | Intersection Set R (Bi) ∩ A (Bi) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1,B6,B7,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | ||

| B2 | B1,B2,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B5 | B1,B2,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B6 | B6 | B1,B2,B5,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B6 | II |

| B7 | B6,B7 | B1,B2,B5,B7,B8,B9 | ||

| B8 | B1,B6,B7,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | ||

| B9 | B1,B6,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5,B9 |

| Barriers | Reachability Set R (Bi) | Antecedent Set A (Bi) | Intersection Set R (Bi) ∩ A (Bi) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1,B7,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | ||

| B2 | B1,B2,B5,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B5 | B1,B2,B5,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B7 | B7 | B1,B2,B5,B7,B8,B9 | B7 | III |

| B8 | B1,B7,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | ||

| B9 | B1,B7,B8,B9 | B2,B5,B9 |

| Barriers | Reachability Set R (Bi) | Antecedent Set A (Bi) | Intersection Set R (Bi) ∩ A (Bi) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | B1,B8 | Ⅳ |

| B2 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B5 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | B2,B5 | ||

| B8 | B1,B8 | B1,B2,B5,B8,B9 | B1, B8 | Ⅳ |

| B9 | B1,B8,B9 | B2,B5,B9 |

| Barriers | Reachability Set R (Bi) | Antecedent Set A (Bi) | Intersection Set R (Bi) ∩ A (Bi) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2 | B2,B5 | B2,B5 | B2,B5 | VI |

| B5 | B2,B5 | B2,B5 | B2,B5 | VI |

| B9 | B9 | B2,B5,B9 | B9 | V |

References

- Behl, A.; Pal, A. Analysing the barriers towards sustainable financial inclusion using mobile banking in rural India. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nambiar, B.K.; Ramanathan, H.N.; Rana, S.; Prashar, S. Perceived service quality and customer satisfaction: A missing link in Indian banking sector. Vision 2018, 23, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Freeman, S.; Cavusgil, S.T. Service quality delivery in a cross-national context. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, R. Making innovation more competitive: The case of Fintech. UCLA Law Rev. 2018, 65, 232. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, E.V.; Weber, T.B.B.; Bomfim, E.L.; Kato, H.T. Measuring customer experience in service: A systematic review. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C. The influence of e-banking service quality on customer loyalty. Int. J. Bank Market. 2019, 37, 1119–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirati, N.; O’Cass, A.; Schoefer, K.; Siahtiri, V. Do professional service firms benefit from customer and supplier collaborations in competitive, turbulent environments? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 55, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paujik, Y.M.; Miller, M.; Gibson, M.; Walsh, K. ‘Doing’socio-political sustainability in early childhood: Teacher-as-researcher reflective practices. Glob. Stud. Child. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Tang, O.; Price, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, W. Supply chain collaboration for sustainability: A literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 194, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palacios-Marques, D.; Guijarro, M.; Carrilero, A. The use of customer-centric philosophy in hotels to improve customer loyalty. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laari, S.; Töyli, J.; Ojala, L. The effect of a competitive strategy and green supply chain management on the financial and environmental performance of logistics service providers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Ajmal, M.M.; Gunasekaran, A.; Khan, M. Exploration of social sustainability in healthcare supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H. Citizen Participation and Political Accountability for Public Service Delivery in India: Remapping the World Bank’s Routes. J. South Asian Dev. 2018, 13, 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Environmental sustainability in the service industry of transportation and logistics service providers: Systematic literature review and research directions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 53, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Tsai, P.H.; Wang, J.L. Improving financial service innovation strategies for enhancing china’s banking industry competitive advantage during the fintech revolution: A Hybrid MCDM model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adebanjo, D.; Teh, P.L.; Ahmed, P.K. The impact of supply chain relationships and integration on innovative capabilities and manufacturing performance: The perspective of rapidly developing countries. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 1708–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, E. The politics of electricity reform: Evidence from West Bengal, India. World Dev. 2018, 104, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A. India’s Unlikely Democracy: Economic Growth and Political Accommodation. J. Democr. 2007, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochor, J.; Arby, H.; Karlsson, I.M.; Sarasini, S. A topological approach to Mobility as a Service: A proposed tool for understanding requirements and effects, and for aiding the integration of societal goals. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2018, 27, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherp, A.; Vinichenko, V.; Jewell, J.; Brutschin, E.; Sovacool, B. Integrating techno-economic, socio-technical and political perspectives on national energy transitions: A meta-theoretical framework. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, R.; Gopalakrishna-Remani, V. Management, social sustainability, reputation, and financial performance relationships: An empirical examination of US firms. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez-Sousa, A. The problems of tourist sustainability in cultural cities: Socio-political perceptions and interests management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rock, M.; Murphy, J.T.; Rasiah, R.; van Seters, P.; Managi, S. A hard slog, not a leap frog: Globalization and sustainability transitions in developing Asia. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicic, S.L.; Lenk, M.M.; Hazen, B.T. A global meaning of supply chain social sustainability. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 988–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puroila, J.; Mäkelä, H. Matter of opinion: Exploring the socio-political nature of materiality disclosures in sustainability reporting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 1043–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirodkar, V.; Beddewela, E.; Richter, U.H. Firm-level determinants of political CSR in emerging economies: Evidence from India. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, B.D.O.; Guarnieri, P.; Camara, S.L.; Alfinito, S. Prioritizing Barriers to Be Solved to the Implementation of Reverse Logistics of E-Waste in Brazil under a Multicriteria Decision Aid Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Have, R.P.; Rubalcaba, L. Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Hazen, B.; Dubey, R. Supply chain social sustainability for developing nations: Evidence from India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 111, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G. Environmental sustainability through green banking: A study on private and public sector banks in India. Oida Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar, R.; Badola, S. Modelling the barriers to online banking in the Indian scenario: An ISM approach. J. Model. Manag. 2018, 13, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A.; Singh, M.; Venkatesh, V.G. Enablers and barriers of mobile banking opportunities in rural India: A strategic analysis. Int. J. Bus. Excel. 2016, 10, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A. The Politics of Social-ecological Resilience and Sustainable Socio-technical Transitions. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 1. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26268112 (accessed on 10 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Vormedal, I.; Ruud, A. Sustainability reporting in Norway–an assessment of performance in the context of legal demands and socio-political drivers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; Van Der Hel, S.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Barau, A. Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarrant, S.P.; Thiele, L.P. Practice makes pedagogy–John Dewey and skills-based sustainability education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.B.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Rezaei, J. Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Sharif, A.; Golpîra, H.; Kumar, A. A green ideology in Asian emerging economies: From environmental policy and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D.; Castro-Fresno, D. Methodology for the development of a new Sustainable Infrastructure Rating System for Developing Countries (SIRSDEC). Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 69, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouzon, M.; Govindan, K.; Rodriguez, C.M.T.; Campos, L.M. Identification and analysis of reverse logistics barriers using fuzzy Delphi method and AHP. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 108, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Ali, S.M.; Rajesh, R.; Paul, S.K. Modeling the interrelationships among barriers to sustainable supply chain management in leather industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.; Lynch, N. Ecological modernization, techno-politics and social life cycle assessment: A view from human geography. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable development: A bird’s eye view. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, A. Beck’s sociology of risk: A critical assessment. Sociology 2002, 36, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.K. Indian power sector reform for sustainable development: The public benefits imperative. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2001, 5, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.L. Achieving Urban Food and Nutrition Security in the Developing World (No. 571-2016-39077). 2000. Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/16037 (accessed on 31 August 2000). [CrossRef]

- Fukuda-Parr, S. From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: Shifts in purpose, concept, and politics of global goal setting for development. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatar, S. Politics, power, poverty and global health: Systems and frames. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2016, 5, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. Development Co-operation Report 2020: Learning from Crises, Building Resilience; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/development-co-operation-report-2020_f6d42aa5-en (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Overman, S. Great expectations of public service delegation: A systematic review. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 1238–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.J.; Kitsis, A.M. A research framework of sustainable supply chain management: The role of relational capabilities in driving performance. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 1454–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobler, M.; Lajili, K.; Zéghal, D. Corporate environmental sustainability disclosures and environmental risk: Alternative tests of socio-political theories. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Grin, J.; Pel, B.; Jhagroe, S. The politics of sustainability transitions. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dasgupta, P. The economics of common property resources: A dynamic formulation of the fisheries problem. Indian Econ. Rev. 2019, 54, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. Analyzing consumer online group buying motivations: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Telemat. Inf. 2018, 35, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Foguet, A.; Lazzarini, B.; Giné, R.; Velo, E.; Boni, A.; Sierra, M.; Trimingham, R. Promoting sustainable human development in engineering: Assessment of online courses within continuing professional development strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4286–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia, S.; Cintra, Y.; Rita de Cássia, S.R.; Lima, F.G. Corporate sustainability management: A proposed multi-criteria model to support balanced decision-making. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, V. Supplier selection using social sustainability: AHP based approach in India. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2014, 2, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kagawa, F. Dissonance in students’ perceptions of sustainable development and sustainability: Implications for curriculum change. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Wells, P. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z. Institutional pressures, sustainable supply chain management, and circular economy capability: Empirical evidence from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.D.; Zuo, J.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zillante, G.; Gan, X.L.; Soebarto, V. Evolving theories of sustainability and firms: History, future directions and implications for renewable energy research. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. Social and political dimensions of environmental protection in Central America. Dev. Chang. 1994, 25, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Carbonara, N.; Costantino, N. Public guarantees for mitigating interest rate risk in PPP projects. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 9, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Županović, I. Sustainable risk management in the banking sector. J. Cent. Bank. Theory Pract. 2014, 3, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Das, S. Status and direction of corporate social responsibility in Indian perspective: An exploratory study. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Gupta, K.; Rani, L.; Rawat, D. Drivers of sustainability practices and SMEs: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kadavil, S.M. Private Labelling, Governance, and Sustainability: An Analysis of the Tea Industry in India. In Business Responsibility and Sustainability in India; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugova, S.; Mudenda, M.; Sachs, P.R. Corporate social responsibility in challenging times in developing countries. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Times of Crisis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedar, B.A.O. The Power of Synthesis: The Pursuit of Environmental Sustainability and Social Equity through Design Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Molombe, J.M.; Mertens, K.; Parra, C.; Poesen, J.; Che, V.B.; Kervyn, M. Socio-political drivers and consequences of landslide and flood risk zonation: A case study of Limbe city, Cameroon. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 707–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.L.; Gunasekaran, A.; Morris, J.; Obayi, R.; Ebrahimi, S.M. Conceptualizing a circular framework of supply chain resource sustainability. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 1520–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.C. Effects of socially responsible supplier development and sustainability-oriented innovation on sustainable development: Empirical evidence from SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Bernardo, M.; Presas, P.; Simon, A. Corporate social responsibility in a local subsidiary: Internal and external stakeholders’ power. Eur. Med. J. Bus. 2019, 15, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathivathanan, D.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A.N. Sustainable supply chain management practices in Indian automotive industry: A multi-stakeholder view. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A.; Delgado, C. Enhancing supply chain performance through supplier social sustainability: An emerging economy perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkkey, H.; Tyson, A.; Choiruzzad, S.A.B. Palm oil intensification and expansion in Indonesia and Malaysia: Environmental and socio-political factors influencing policy. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 92, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Goyal, P.; Kumar, V. Prioritizing CSR barriers in the Indian service industry: A fuzzy AHP approach. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2019, 66, 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chlela, M. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in the Lebanese Banking Sector: A Reality or a Myth? Ph.D. Thesis, Notre Dame University-Louaize, Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Micheli, P.; Bolzani, D. The evolution of sustainability measurement research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 661–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, R.; Agrawal, R. Building a society conducive to the use of corporate social responsibility as a tool to develop disaster resilience with sustainable development as the goal: An interpretive structural modelling approach in the Indian context. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhya, B. CSR Reporting Practices in Indian Private Sector Banks. Sumedha J. Manag. 2018, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Prakash, A. Developing a framework for assessing sustainable banking performance of the Indian banking sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, A.S.M.; Eldahan, O.H. Assessing the Level of Sustainability in the Egyptian Banking Sector. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S. Determinants of the credit risk in developing countries after economic crisis: A case of Turkish banking sector. In Global Financial Crisis and its Ramifications on Capital Markets; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Aneja, R.; Ahuja, V. An assessment of socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 pandemic in India. J. Public Aff. 2020, e2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, H. Banking deregulation around the world, 1970s to 2000s: The impact on unemployment. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2012, 24, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.K.; Das, M.C. Selection of the barriers of supply chain management in Indian manufacturing sectors due to COVID-19 impacts. Oper. Res. Eng. Sci. Theory Appl. 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Saunoris, J.W. Unemployment and international shadow economy: Gender differences. Appl. Econ. 2017, 49, 5828–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, M.; Naseem, F.; Masso, I.C. Teacher-directed learning to self-directed learning transition barriers in Pakistan. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2019, 61, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisuria, A. Neoliberal development and struggle against it: The importance of social class, mystification and feasibility. Aula Abierta 2018, 47, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, C.A. Barriers to Accessing Higher Education. In Widening Participation, Higher Education and Non-Traditional Students; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Muchangos, L.S.; Tokai, A.; Hanashima, A. Analyzing the structure of barriers to municipal solid waste management policy planning in Maputo city, Mozambique. Environ. Dev. 2015, 16, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaba, S.; Bhar, C. Analysing the barriers of lean in Indian coal mining industry using integrated ISM-MICMAC and SEM. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 2145–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; He, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Iqbal, M. Green, lean, six sigma barriers at a glance: A case from the construction sector of Pakistan. Build. Environ. 2019, 161, 106225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Barua, M.K. Flexible modelling approach for evaluating reverse logistics adoption barriers using fuzzy AHP and IRP framework. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 30, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodh, S.; Asokan, P. ISM and Fuzzy MICMAC application for analysis of Lean Six Sigma barriers with environmental considerations. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2018, 9, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Almubark, S.; Qattan, A.M.; Cenkier, A.; Kosycarz, E.A. Barriers to the implementation of public-private partnerships in the healthcare sector in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233802. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, S.; Nehra, V.; Luthra, S. Identification and analysis of barriers in implementation of solar energy in Indian rural sector using integrated ISM and fuzzy MICMAC approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Shankar, K.M.; Kannan, D. Achieving sustainable development goals through identifying and analyzing barriers to industrial sharing economy: A framework development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso-Cerón, A.M.; Kafarov, V. Barriers to social acceptance of renewable energy systems in Colombia. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2015, 10, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A.; Sharma, V.; Agrawal, R.; Dwivedi, A.; Dwivedi, P.; Joshi, K.; Barthwal, M. Prioritization of barriers to energy generation using pine needles to mitigate climate change: Evidence from India. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Sekhar, C.; Vyas, V. Barriers to internationalization: A study of small and medium enterprises in India. J. Int. Entrep. 2016, 14, 513–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, F.; Rahman, Z. Modeling the barriers of Indian telecom services using ISM and MICMAC approach. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2017, 11, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.H.; Kristensen, M.A.N.; Wenzel, K.; Agustín, L.S.R. Barriers for Economic, Political and Social Empowerment in Relation to Financial Inclusion of Urban Women Workers in Faridabad. Master Thesis, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 2019; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Battams, S.; Townsend, B. Power asymmetries, policy incoherence and noncommunicable disease control-a qualitative study of policy actor views. Crit. Public Health 2019, 29, 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Malhotra, V.; Kumar, V. Identification of key barriers affecting the cellular manufacturing system by ISM approach. Int. J. Process Manag. Benchmarking 2017, 7, 466–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil “Modified ISM/TISM process with simultaneous transitivity checks for reducing paired comparisons”. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2017, 18, 331–351. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Dhillon, V.S.; Singh, P.L.; Sindhwani, R. Modeling and analysis for barriers in healthcare services by ISM and MICMAC analysis. In Advances in Interdisciplinary Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastrollo-Horrillo, M.A.; Rivero Díaz, M. Destination social capital and innovation in SMEs tourism firms: An empirical analysis in an adverse socio-economic context. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1572–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C.L.; García, J.L. Evaluating the impact of ERP systems on SC performance with ISM. Wpom-Work. Pap. Oper. Manag. 2017, 8, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.; Narkhede, B.E.; Gardas, B.B.; Luong, H.T. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing sustainable practices. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, G.; Srivastava, S.K.; Srivastava, R.K. Analysis of barriers to implement additive manufacturing technology in the Indian automotive sector. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.E.; Sridharan, R.; Kumar, P.R. Analyzing the interactions among barriers of sustainable supply chain management practices. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 937–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Suresh, M. Total interpretive structural modelling: Evolution and applications. In International Conference on Innovative Data Communication Technologies and Application; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Roshani, K.; Owlia, M.S.; Abooie, M.H. A research note on the article of “Quality framework in education through application of interpretive structural modeling”. Tqm J. 2019, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayant, A.; Azhar, M. Analysis of the barriers for implementing green supply chain management (GSCM) practices: An interpretive structural modeling (ISM) approach. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daneshgar, M.; Abdolvand, M.A.; Heidarzadeh Henzaei, K.; Khoon Siavash, M. Modeling Corporate Brand Identity in the Banking Industry. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 652–678. [Google Scholar]

- Bux, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ahmad, N. Promoting sustainability through corporate social responsibility implementation in the manufacturing industry: An empirical analysis of barriers using the ISM-MICMAC approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S. Barriers to blockchain adoption in health-care industry: An Indian perspective. J. Glob. Oper. Strat. Sourc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwane, V.S.; Yadav, V.S.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B.E.; Gardas, B.B. Sustainable development challenges of the biofuel industry in India based on integrated MCDM approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, A.J.; Chawla, V.; Sunder, M.V.; Kumar, R. Barriers to service recovery in B2B markets: A TISM approach in the context of IT-based services. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Tyagi, M.; Garg, R.K. Assessment of Barriers of Green Supply Chain Management Using Structural Equation Modeling. In Recent Advances in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 441–452. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, N.U.; Kashiramka, S.; Singh, S.; Sushil. A hierarchical model of the determinants of non-performing assets in banks: An ISM and MICMAC approach. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 3834–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Al-Zabidi, A.; AlKahtani, M.; Umer, U.; Usmani, Y.S. Assessment of Supply Chain Agility to Foster Sustainability: Fuzzy-DSS for a Saudi Manufacturing Organization. Processes 2020, 8, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubric, M. Drivers, barriers and social considerations for AI adoption in business and management: A tertiary study. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y. Active conflict or passive coherence? The political economy of climate change in China. Environ. Politics 2010, 19, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duclos, L.K.; Vokurka, R.J.; Lummus, R.R. A conceptual model of supply chain flexibility. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2003, 103, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibin, K.T.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Luo, Z.; Papadopoulos, T.; Roubaud, D. Frugal innovation for supply chain sustainability in SMEs: Multi-method research design. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Classification | |

|---|---|---|

| Employer | Financial service organization | |

| Type of the organisation | Public | Private |

| Number | 8 | 15 |

| Year(s) of experience in the present organisation | >2 Years | |

| Year(s) of experience within the sector | >5 Years | |

| Educational qualification | All have Bachelor degree | |

| Barriers | Definition of Factors | References |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty of implementing CSR (corporate social responsibility) (B1) | This factor refers to the no-mutual trust relationship of firms and governments liaise which impede CSR implementation in banks. | [83,84] |

| Antisocial considerations (B2) | This factor refers to the non-supportive social responsively of a bank that will impede the bank to achieve organisational objectives. | [85,86] |

| Unemployment (B3) | This factor refers to the unemployment fluctuations that affect the healthiness of the market. | [87,88,89,90,91] |

| Class-system (B4) | The class-system refers to the distinction of the social stratum of society which discourages the promotion of autonomy and can ultimately lead to a lack of interest and motivation. | [92,93,94] |

| Unstable political climate (B5) | The institutional weakness and the lack of cooperation between banks or banks’ stakeholders contributed to the instability. | [28,95,96] |

| Lack of infrastructure considerations (B6) | This factor refers to the lack of basic infrastructure in rural areas such as power, roads, skilled workers, and resource availability. | [97,98,99] |

| Lack of regulatory framework for service sector (B7) | This factor stands for the ineffective regulatory frame, regulations inadequate to promote services, lack of a favourable provision for the banking sector. | [1,100,101,102,103] |

| Lack of government regulations (B8) | Incentives and benefits provided by the government do not support the adoption of sustainability in the service supply chain. | [1,95,103,104,105,106] |

| Lack of political coherence (B9) | Lack of political coherence refers to how the political leaders implement the policies for banking sector growth. | [28,107,108] |

| Profile | Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employer | Financial service organisation | |||

| Type of the organisation | Public | Public | ||

| Number | 11 | 4 | ||

| Position | Department Head | Manager | Researcher | |

| 5 | 8 | 2 | ||

| Year(s) of experience in the present organisation | <2 Years | >2 Years | ||

| 2 | 13 | |||

| Year(s) of experience within the sector | <5 Years | >5 Years | ||

| 6 | 9 | |||

| Educational qualification | Bachelor | Master | Ph.D. | |

| 4 | 9 | 2 | ||

| Barriers | B9 | B8 | B7 | B6 | B5 | B4 | B3 | B2 | B1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | A | X | V | V | A | V | O | A | |

| B2 | V | V | V | V | X | V | V | ||

| B3 | A | A | O | A | A | X | |||

| B4 | A | A | A | A | A | ||||

| B5 | V | V | V | V | |||||

| B6 | O | A | A | ||||||

| B7 | A | A | |||||||

| B8 | A | ||||||||

| B9 |

| (i, j) Values in SSIM | Conversion Value in IRM | |

|---|---|---|

| (i, j) | (j, i) | |

| V | 1 | 0 |

| A | 0 | 1 |

| X | 1 | 1 |

| O | 0 | 0 |

| Barriers Bi | Barriers Bj | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | |

| B1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B9 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Barriers Bi | Barriers Bj | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | B8 | B9 | Driving Power | |

| B1 | 1 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| B2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| B3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| B4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| B5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| B6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| B7 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| B8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| B9 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Dependence | 5 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 48 |

| Barriers | Reachability Set R (Bi) | Antecedent Set A (Bj) | Intersection Set R = R (Bi) ∩ A (Bj) | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1, B8 | B1, B2, B5, B8, B9 | B1, B8 | IV |

| B2 | B2, B5 | B2, B5 | B2, B5 | VI |

| B3 | B3, B4 | B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7, B8, B9 | B3, B4 | I |

| B4 | B3, B4 | B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7, B8, B9 | B3, B4 | I |

| B5 | B2, B5 | B2, B5 | B2, B5 | VI |

| B6 | B6 | B1, B2, B5, B6, B7, B8, B9 | B6 | II |

| B7 | B7, B9 | B1, B2, B5, B7, B8, B9 | B7, B9 | III |

| B8 | B1, B8 | B1, B2, B5, B8, B9 | B1, B8 | IV |

| B9 | B9 | B2, B5,B9 | B9 | V |

| Barriers | Driving Power | Dependence | Driving Power/Dependence | MICMAC Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 6 | 5 | 1.2 | 3 |

| B2 | 9 | 2 | 4.5 | 1 |

| B3 | 2 | 9 | 0.222222222 | 6 |

| B4 | 2 | 9 | 0.222222222 | 6 |

| B5 | 9 | 2 | 4.5 | 1 |

| B6 | 3 | 7 | 0.428571429 | 5 |

| B7 | 4 | 6 | 0.666666667 | 4 |

| B8 | 6 | 5 | 1.2 | 3 |

| B9 | 7 | 3 | 2.333333333 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.-K.; Nalluri, V.; Lin, M.-L.; Lin, C.-T. Identifying Decisive Socio-Political Sustainability Barriers in the Supply Chain of Banking Sector in India: Causality Analysis Using ISM and MICMAC. Mathematics 2021, 9, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9030240

Chen W-K, Nalluri V, Lin M-L, Lin C-T. Identifying Decisive Socio-Political Sustainability Barriers in the Supply Chain of Banking Sector in India: Causality Analysis Using ISM and MICMAC. Mathematics. 2021; 9(3):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9030240

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wen-Kuo, Venkateswarlu Nalluri, Man-Li Lin, and Ching-Torng Lin. 2021. "Identifying Decisive Socio-Political Sustainability Barriers in the Supply Chain of Banking Sector in India: Causality Analysis Using ISM and MICMAC" Mathematics 9, no. 3: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9030240