Abstract

This paper examines the positive aspects of aging. Some items, such as valuable and rare stamps, old coins, works of art, and antiques, become more expensive over time. More popular examples demonstrating the positive effect of aging that influences price are the aging of boutique wine and artisan cheese. The present paper examines the wine aging process that brings about quality improvement. This process also leads to determining (i) optimal aging periods for different wines; (ii) optimal grape juice inventory allocations and prices for different wines; (iii) optimal quantities of different kinds of wine; and (iv) the time durations of wine production and consumption from each vintage. These aspects are considered in an environment in which the demand increases over time due to the aging and rarity of the product.

JEL Classifications:

D2; D21; D4; L12

1. Introduction

The issue of optimal pricing and inventory policy for perishable products has been considered for decades. In a recent paper Avinadav, Herbon, and Spiegel (AHS) [1] discuss the optimal pricing, ordered quantity, and replenishment period for perishable items. The basic presumption of the AHS model is that the perishability or deterioration of the consumed products over time is due to their loss of freshness. The AHS paper is cited by several authors, including Janssen et al. [2], Ek Peng et al. [3], and others. They extend the issue of the optimal dynamic pricing and ordering policy of perishable products under various scenarios. Change in the scent of perfume with aging [4] is a good example of product deterioration. It is explained by the interactions between a range of perfume materials and alcohol, water, air, elevated temperatures, and daylight. In their review, Turek and Stintzing [5] provide a summary of a possible deterioration process in oils and the factors affecting their stability. Temperature, light, and oxygen availability are recognized to have a crucial impact on essential oil integrity.

Food products such as dairy, fruit, vegetables, or meat, including beef, chicken, and other meat items, and food products in general are subject to spoilage. Gram et al. [6] claim that food spoilage is a complex process and that excessive amounts of foods are lost due to microbial spoilage, even with modern preservation techniques. Moreover, the heterogeneity of raw materials leads to different processing conditions and thus to food spoilage. Based on knowledge of the origin of food, the spoilage process can be predicted by considering temperature, atmosphere, etc.

However, the list can be extended to many other items, such as medical products, drugs, and batteries. Jian et al. [7] discuss the inventory management of deteriorating medical products and drugs. They establish a stochastic lead time inventory model for deteriorating drugs with fixed demand. Marr et al. [8] investigate the issue of batteries used for light or electric vehicles (EV). They examine the battery voltage over time.

In addition, the deterioration process has also been considered with regard to cosmetic items such as special perfumes, soaps, and other perfume products. During their shelf-life period, both the quality and the price of these items are reduced. Other examples are cigars and cigarettes. The aroma of tobacco deteriorates over time, reducing the quality of the product and the benefit from its consumption. In all of the abovementioned items, as well as in many similar items, price discounting due to the age of the product is considered. The basic axiom is that product aging negatively affects the price. In these examples, the possibility of positive effects of aging does not exist at all.

The positive aspect of aging is rare. Several products described below reveal the positive effects of aging.

For example, due to their aging and rarity, antiques become more expensive over time. In addition, for collectible items such as valuable stamps, old coins, art objects, and antiquities, positive aging may exist. The most popular examples that demonstrate the positive effect of aging that influences price are the aging of wine and cheese. Durham et al. [9] discuss the case of artisan cheese and determine how to utilize an economic model to achieve the highest net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return in these kinds of cheese production. Another example of the positive effect of aging over time is in the aging of fine red wine. The process of wine aging preserves and magnifies the wine properties. For this purpose, the use of oak barrels generates chemical reactions that modify the final quality and leads to better aroma from wood, flavor, stability, and clarification [10,11,12,13]. The aging process can vary with the type of wine, origin of the grapes, wine age, etc. [14,15]. The use of oak wood barrels is not only very beneficial but also very expensive, extending over long periods from 6 to 18 months and generating economic costs. This issue is discussed extensively by Morata [16], Tao et al. [17], and Rasines-Perea et al. [18]. It is difficult to assess and decompose all components of the final product of bottled red wine, since there are many factors that should be considered. Different issues regarding cost management have been discussed by Ciaponi [19], González-Gómez and Morini [20], and Biondi et al. [21], among others. Marone et al. [22] use the full-cost method, which is also implemented by Ghelfi [23], Torquati [24], and Antonelli and D’Alessio [25].

In recent decades, new approaches have been developed for barrel aging in order to find new alternatives that are more suitable, affordable, and feasible for sanitizing the process. Two examples are the use of materials other than wood or the use of wood chips [10]. In recent years, wine aging technologies have been developed to shorten and reduce the cost of the aging process, i.e., to accelerate the aging process [26]. For example, new materials such as acacia [27], cherry [28], chestnut [29,30], mulberry [28], and Spanish oak [31,32,33] are considered in order to replace the common use of American and French oak barrels, which are both expensive and limited in supply. Although oak barrels are used as a traditional method to improve wine quality, new technologies have also been developed that are designed with wine quality in mind—for instance, the use of wood fragments [34,35] or stainless-steel tanks as a substitute for the oak barrel [36,37,38,39]. Physical methods such as ultrasound have been suggested by Chang and Chen [40] and Leonhardt and Morabito [41].

The model introduced below discusses wine aging that is generated during the period in which the wine remains in the barrel. Marone et al. [22] distinguish between different stages of wine production costs. These stages include grape production, vinification, aging, bottling, and marketing. Bottling is sometimes an important stage for wine aging, when wines are directly aged in bottles [42,43]. Among the factors that affect the quality of wine during bottling are temperature [44,45,46], the nature of the glass bottle [47,48], and oxygen content [49,50]. When the wine is bottled, its quality and taste also improve so that wine bottling can be regarded as a second phase of wine aging [17]. However, this further phase of aging is beyond the scope of the model presented in this paper.

The aging process using barrels may bring about quality improvement and leads to several important matters for consideration: (1) the optimal aging period for different kinds of wine; (2) the optimal inventory allocation and prices for the different kinds of wine; and (3) the optimal quantity of the different kinds of wine consumed from each vintage.

In the model below, T represents the time constraint for each vintage. During the entire vintage period, T, some of the time is devoted to the production period, i.e., the aging process during which the product is not consumed. In the remaining time, the improved wine is consumed.

In recent years, researchers have considered the optimal inventory policy trajectory when demand is sensitive to and negatively affected by price and time [51].

The primary question examined in these papers concerns the number of ordered units that are sold over time, assuming that inventory which is held for a longer time becomes more expensive as it approaches the expiration date. The demand for the product also decreases due to loss of product freshness, deterioration of its quality, etc.

The current paper presents an applied case of demand in which opposite effects exist. The demand over time increases due to the aging and rarity of the product. Similar circumstances may be found in the cases of valuable collections as mentioned above. The example discussed in this paper considers the case of grapes that are first converted into wine, whose quality is then improved by the aging process.

The discussion includes the phenomenon of quality improvement over time. It deals with a variety of grape of a specific year (vintage) that can be used for the production of either simple grape juice or several qualities of wines. An additional factor that affects fine wine quality and prices is the weather, in terms of the temperature and precipitation fluctuation during the year in which the grape was grown.

Findings that relate to wine quality and climate are presented in the early work of Amerine and Winkler [52]. Much later, Gladstones [53] discusses extensively the weather conditions of temperature and precipitation that impact grape growing. Empirical work that examines weather influences on the prices of fine wine such as Bordeaux has been conducted by Ashenfelter [54,55,56,57]. Jones and Storchmann [58] confirm the findings of Ashenfelter and support the hypothesis that global warming positively affects Bordeaux wine. In recent decades, Chevet et al. [59] and Ashenfelter and Storchmann [60] find the same result regarding temperature and wine price.

The impact of temperature on wine is also essential to the wine storage model. The optimal temperature for wine storage was discussed recently by Cadeddu and Cauli [61]. They examine the issue of optimal storage temperature and optimal cellar depth to achieve the highest quality of the wine. Researchers also extend their investigations of the wine industry with questions regarding wine tasting that includes three stages of analysis. The first stage is evaluation of the appearance based on the color, elasticity, and transparency of the wine. The second stage is based on the strength of the aroma, where more varieties of aroma indicate the greater complexity and sophistication of the wine. The third stage includes gustative analysis and the analysis of ingredients such as sugar, alcohol, tannins, and acids; see De Marchi [62]. This kind of analysis does not consider the aging aspects that are focused on in the current paper.

In the last several years, there has been a growing body of economic literature that assesses the return on as well as the risk of investing in fine wine. In general, cross-section models are distinguished from time-series models. The studies of Ashenfelter [63] and Ashenfelter et al. [64] are cross-section analyses based on an earlier work of Ashenfelter [65] that was published in Liquid Assets. Ashenfelter et al. [64] suggests an econometric model that explains mature wine prices that are related to the wine’s age and to the weather. The model proves the assessment of the quality of the Bordeaux vintages and predicts prices of mature wines. The research of Ashenfelter et al. [64] is used as a basis for other research in which investments in wine are compared to an alternative financial asset in terms of rate of return and risk. Haeger and Storchmann [66] and Jones and Storchmann [58] report the cross-sectional real rate of returns for selected wines. Wood and Anderson [67] analyze three unique wine prices: “when the wine is young, plateauing out around optimal drinking time, before increasing again in value as the wine becomes an ‘antique’ wine” (p. 146). Krasker [68] conducts the first economic time-series analysis of the rate of return on aging wine. Based on his findings, a significant gap exists between the rate of return on holding wine and risk-free U.S. Treasury bills. Jaeger [69] found that for a wine portfolio similar to that of Krasker [68], wine had better performance compared to Treasury bills due to the different time period and the lower storage cost. Weil [70] compares the rate of return of a hypothetical investor that invests in the stock market according to the Dow Jones with investments in fine wine during the same time period. Weil concludes that the former return is higher than the latter. Similar results are found by Burton and Jacobsen [71], who compare the returns from storing Bordeaux wines during the years 1986 to 1996 and investments in Treasury bills. They report that wine yields lower returns than stock and that wine investment is even riskier. Similarly, Fogarty [72] finds “…that despite the return to Australian wine being lower than the return to standard financial assets, wine does provide a modest diversification benefit” (p. 119). Masset and Henderson [73] find that wine can provide diversification risk reduction benefits and calculate optimal portfolio shares for equity, wine, and art for investors with different preferences. Similar results are found by Masset and Weisskopf [74], who show that adding fine wine to the portfolio during the 2008 crisis was beneficial for private investors.

As discussed above, wines require time for quality improvement through aging, while the wine is stored in wooden barrels in the winery. The aging of the wine over time “generates” different qualities of wine. A longer aging process enhances the quality of the liquid that began as grape juice and becomes improved wine.

A longer aging period affects the demand and supply sides, i.e., the required production costs. Thus, several questions need to be considered by the winemaker:

- (a)

- What is the optimal quantity of grapes that should be produced, and its allocation as a raw material for simple grape juice, wine of simple quality, and high-quality wine?

- (b)

- Since the different wine quality levels are affected positively by the duration of aging of the wine, the question is how the total time, T, of the vintage is allocated between the production time of the wine inventory aging process and the consumption time of the final goods (fine red wines).

- (c)

- The answers to (a) and (b), above, determine the pricing of the three different grape beverages.

- (d)

- The last question for consideration is how the sensitivity of demand towards the quality of the products affects other variables beyond optimal quantity, including prices, the time allocated for quality improvement, and the time of consumption of the products. In order to answer these questions, the present paper develops a model with several basic characteristics.

2. The Model

The model that is developed is an extension of a previous model of Goodhue et al. [75]. The differences between the model of Goodhue et al. [75] and the current model are summarized below:

- (a)

- The demand and the cost functions of Goodhue et al. [75] are both continuous, while in our model, both are discrete.

- (b)

- In the current model, the demand curve represents a negative linear relationship between price and quantity demanded, while the Goodhue et al. [75] model demonstrates how the price affects the quantity demanded that is diminishing exponentially.

- (c)

- The current model deals with the question of how the price and the quality of the wine are determined simultaneously in a monopolistic environment where the price is diminishing with respect to quantity and increasing with respect to the aging of the product. In the model of Goodhue et al. [75], the producer that is also the seller maximizes profit in a competitive market where the price is determined externally to the producer. The producer achieves the maximization target by determining aging that leads to the desired price.The previous points can be explained in further detail as follows.The model of Goodhue et al. [75] develops a special case of a wine producer that faces a competitive market, where the market price is given and constant, i.e., the producer is a price taker and has to determine the optimal quality and quantity for a given price. The quality is affected by determining aging duration in order to achieve optimal quality and quantity that maximize profit at the given market price.In the present model, the market demand encompasses price, quantity, and quality (including duration of both production and consumption periods as simultaneously determined decision variables). Both the price and the other variables mentioned above are influenced by the winemaker’s decisions. They are derived not only on the demand side but also on the production costs side, as presented in (f) below.

- (d)

- The present model assumes for simplicity a discount rate, r, of zero, while the Goodhue et al. [75] model assumes that r is positive.

- (e)

- In the model of Goodhue et al. [75], the grape juice production decision is determined at the beginning of the vintage, only for the purpose of supplying one kind of wine with a specific quality. In the present model, the grapes may be produced for three purposes. They may be used for simple grape juice sales, or as a raw material for the production of a simple wine and a high-quality wine.

- (f)

- According to Goodhue et al. [75], cost of production is decomposed into two components. The cost of grape juice production as a raw material for wine is assumed to be positive and constant, i.e., in our model , while in the Goodhue et al. [75] model, the marginal costs of wine production are increasing . In the current paper, the marginal cost of grape juice production either as a final good or as wine input is positive and constant. Other costs of non-grape inputs (required to control for wine grape heterogeneity) are constant for each unit of the wine during the storage period. This is determined for simplicity and in order to obtain an analytical solution.

- (g)

- In the model developed below, the production cost function with respect to grape juice differs from the cost of the aging process. This distinguishes between three kinds of costs:

- (I)

- costs that increase linearly with the quantity of grape juice that is used as raw material for any kind of wine.

- (II)

- costs that are related to the aging process and increase with the generated aging time and the output of the final good that is fine wine. While the aging incurs greater costs, it generates higher quality and thus more consumer satisfaction from the use of the fine wine.

- (III)

- other costs of wine production that are not affected by the total output of wine and are thus considered as fixed costs. These costs are similar to the costs used by Goodhue et al. [75]. This kind of cost, such as temperature control, is assumed to be a fixed cost with respect to the quantity of grape juice stored for each given period. This is also the basic assumption of Goodhue et al. [75].

- (h)

- Goodhue et al. [75] assume that the wine price is an increasing concave function of quality. In contrast, in the present model, the wine price increases linearly with respect to quality. A discussion about fine wine price in which the price of fine wine indicates quality was presented in recent decades by D’Alessandro and Pecotich [76], Hopfer et al. [77], and Juan et al. [78].

The aging process also varies depending upon the type of wine [10]. It is emphasized that the model developed below relates to the case of red wines such as Bordeaux and not necessarily to white or rose wine. Red wine is well aged. With regard to white wine, it was believed for many years that the aging process was not adequate. White wine suffered a decrease in quality since wood masked the white wine components and contributed to oxidative processes [79]. The same argument is used by several additional authors, such as Rashmi Urkude et al. [80], stating that white wines are not stored for a long period, contrary to red wines. Van Wyk and Silva [81] also argue that white wines do not improve during storage, while red wines can remain in storage for several decades under a stable temperature.

The scope of the model does not cover white wine. The present paper provides a mathematical model relevant only to red fine wine since white wines typically do not age as long as red wines.

Let us present the model:

Assume that a wine producer that is also a seller purchases grape juice at a given unit price of , either for selling it as a final product or as a raw material for producing different qualities of wineThe total amount of grape juice Q is distributed among the three following items. units are sold as a final good (grape juice), at each unit of a time period during the entire period T of a given vintage of the grapes. A portion of the remaining units of the grape juice is used for a final simple wine, and units of the grape juice are used for high-quality wine.

The demand at each time period for wine or grape juice is linear and equal to the following:

Therefore, the profit from selling the grape juice as a final good is:

where T is defined as a duration period of the vintage for any type of winery beverage.

The revenue from selling units of simple wine is calculated as follows:

where is defined as the consumption period of the simple wine.

The left term in the bracket represents the price of each unit of the simple wine. The price increases with aging. The initial reservation price for each unit is . It is assumed that it is greater than the initial reservation price of the grape juice as a final good. In addition, due to the aging process, the quality of the wine increases during aging time t, increasing the final price per unit by We ignore the possibility of that represents the deterioration of quality during aging process of white wine. is the quantity of simple wine consumed at each unit of time.

Similarly, the revenue from selling units of high-quality wine over time is:

In order to find profit maximization, we have to subtract costs that are decomposed into two parts:

- Production cost of grape juice as a raw material is:

- Additional cost includes quality improvements due to aging. This cost function per unit increases linearly over the aging time. Thus, is the total cost of quality improvement of each unit of simple wine over time. Similarly, is the total cost of high-quality wine improvement, where is defined as the consumption period of the high-quality wine.

The producer’s revenues are decomposed into three parts that depend on the quality of grape juice. The grape juice produced is distributed among simple grape juice, simple wine, and high-quality wine. The quality of wine depends on the aging process. A longer aging period improves the quality of wine. Aging time positively influences the demand for wine, i.e., the increased price of the wine that is sold. Aging time also influences the production cost of the wine. A longer duration of aging positively influences the costs. The cost of aging the wine includes the construction cost of the winery, which increases with the time that the wine remains in oak barrels. In addition, the costs include the maintenance costs of the winery, which are also affected by the aging time of the wines. The production costs are affected by the output as well as by the duration of the production. Furthermore, for simplicity, it is assumed that the cost is positive and increases linearly with respect to aging duration and production. The positive effect of aging on demand and the cost effect of aging lead to the question regarding the optimal decision variable, i.e., the optimal aging that has to be determined by the producer. Based on the preceding discussion, the objective function is profit maximization with respect to several decision variables: the optimal quantities, pricing, and aging duration that determine production and consumption durations. Therefore, the objective is to maximize the profit function, , as follows:

The maximization of is with respect to several dependent variables that also determine optimal pricing , which are introduced below, using F.O.C. of equilibrium, defining C4 as fixed cost.

From this derivative, the optimal quantity of units of grape juice sold is introduced by:

The next derivations are with respect to and :

From this derivative, the optimal quantity of simple wine at optimum is:

The derivative with respect to is:

or

Based on Equations (5) and (7), we find the optimal aging time period, :

and the optimal quantity of simple wine,, as follows:

The same procedure is followed for variables that include high-quality wine:

Therefore, the optimal quantity of high-quality wine,, is as follows:

Based on Equations (11) and (13):

and

Based on the results of all five parameters, above, the optimal prices of the three kinds of grape beverages are:

where is the price of each sold unit of the grape juice.

and are the optimal prices of simple and high-quality wines, respectively.

Based on the above 5 optimal decision variables, the following additional results are derived:

The grape juice is consumed over the entire vintage period T.

The consumption period of simple wine is:

The total consumption of the simple wine is:

The time duration of the high-quality wine is:

and the total consumption of the high-quality wine is:

Based upon the optimal values of , the total profit, , from all three kinds of grape beverages is:

or

3. Comparative Static Analysis

This section considers the question of how changes in the parameter α, as well as other independent variables, affect the values of the dependent variables t2, Q2, P2, T-t2, Q2(T-t2), and π. The effect is presented in Table 1 and Table 2 below.

Table 1.

The effect of independent variables on the decision variables.

Table 2.

The effect of independent variables on the decision variables.

Table 2 illustrates the effect of an increase in the independent variables and their influence on the values of dependent variables t3, Q3, P3, T-t3, Q3(T-t3), and π. These influences relate to high-quality wine, .

Based on the comparative static analysis presented in Table 1 and Table 2, Appendix A, and Equations (8), (9), (14), (15) and (17)–(22), several implications and results are discussed below.

While some results are straightforward, others require certain further explanation and investigation.

First, we discuss the effect of :

- The parameter determines the benefit or satisfaction from drinking a simple wine after a certain aging time. An increase in encourages the seller to produce more wine, leaving less juice for grape juice consumption; to charge a higher price for the wine; and to enjoy a higher quality of simple wine by increasing the aging time, thereby shortening the period of simple wine consumption.

- Consuming more units of the simple wine during a shorter period may increase or decrease the total consumption of the simple wine during the entire period. If the percentage decrease in the period of consumption at each time unit is larger than the percentage increase in consumption at each period, then the total consumption during the entire vintage period decreases and vice versa. This depends upon the value of parameter in combination with the other influential variables, such as , , and T.

- has the same effect on the profit of the wine producer. At certain values of ,, , , and T, improvement of the aging process on the demand and benefit may lead to profit reduction. This means that the aging process is not necessarily desired. This negative effect of the influence of may exist in cases of shorter vintage period T, and/or high reservation price , and/or low costs of production of and .

- An increase in the value of affects consumption and profit.

Changes in represent the subjective consumer evaluation of wine aging. A larger represents higher evaluation due to aging, which has a larger positive effect on the perceived quality of the wine. However, the benefit is obtained by extending the aging production period of the wine. This is achieved by lower consumption time and higher production time (aging). Therefore, the increase in leads to an increase in the price of the wine at each unit of time, and to an increase in consumption at any unit of consumption time but during a shorter consumption period.

- It is possible that the consumption period decreases very significantly due to the increase in , so that the total profit is reduced.

- This is a very important implication from the point of view of the producer. It indicates whether to control and sometimes partially reduce or eliminate the positive effect of if is indeed endogenous for the producer.

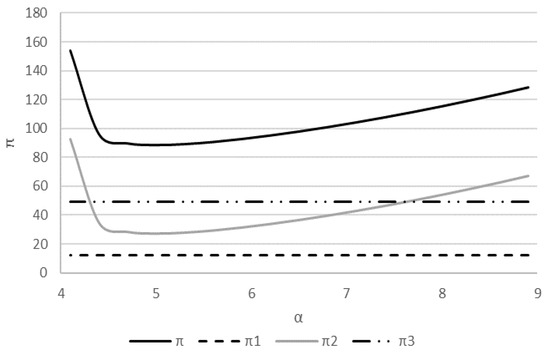

The above ambiguous effect of on revenues or profits is illustrated graphically in Figure 1. The figure is based on certain values of A1, A2, A3, and Ci. It shows negative and positive effects of on profits at different ranges of .

Figure 1.

The effects of changes in parameter α on profits. π1 measures the total profit from grape juice sales; π2 measures the total profit from low-quality wine sales; π3 measures the total profit from high-quality wine sales.

In the discussion below, we illustrate the ambiguous effect of parameter on profits for the following specific values: A1 = 8, A2 = 10, A3 = 12, C1 = 4, C2 = 4, C3 = 4, T = 3, and β = 5. Figure 1 presents the effects of changes in parameter α on profits.

At a given that is determined exogenously, the seller that faces the parameter has to respond and determine aging production duration as well as wine quality and consumption duration. Two conflicting impacts of may influence the decision variables and, as a result, the profit that is derived by . On one hand, an increase in more significantly supports the aging process, increasing the quality and price of simple wine. This may encourage the tendency to shorten the duration of higher-quality wine consumption. On the other hand, a higher value of means that by accelerating aging, the seller can achieve a certain quality level of wine by a shorter duration of production for the sake of a longer consumption duration. These conflicting effects may bring about different results of the decision variables. This may lead to different results of the effect of values on the final profits. These are also demonstrated in Figure 1. It indicates how changes in values may either increase or decrease profits for different gaps between the aging processes of and β (see also Equations (A6) and (A7) in the Appendix A).

Another implication arises from technological improvement, i.e., reduction in. It is expected that generating improvement in the production process or implementing less expensive and more efficient methods results in an increase in profit. This occurs by extending the aging process time that allows for the benefits of innovative technology and the consumption of fewer units of wine sold at a higher price during a shorter consumption period.

Technological improvement and/or reduction in the input prices lead to the following results: a. a shorter consumption period of high-quality wine; b. increased high-quality wine consumption at any point during the consumption period; c. an increased price of high-quality wine; and d. an ambiguous effect on the total consumption and profit during the entire consumption period.

An additional important implication is the question of how the monopoly power of a firm may affect profit from sales of aged wine. Monopoly power is measured and increases according to potential profit maximization (. As expected, a monopoly gains more profit under greater monopoly power. This can be achieved by reducing the aging period, charging a lower price during a larger consumption period, and selling a larger quantity at any time during the consumption period.

These results lead to important conclusions. In the case of the wine market, where the aging process has a positive effect on quality, a monopoly market of wine is preferable to a competitive market structure. The monopoly solutions lead to a more efficient situation. By utilizing a shorter aging period, the monopoly increases not only its profit but also the total high-quality output and decreases prices. This increases the benefit for consumers. Thus, the total social welfare also increases.

4. Conclusions

The present paper examines the issues of optimal pricing, production, and consumption of products that exemplify the process of “positive aging”. The aging over time occurs due to a factor that is measured and determined exogenously. The effect of parameter on production and consumption periods as well as on profits is discussed. Some results are straightforward, while others are surprising and counterintuitive. One result reveals the possibility that an increase in the aging process by exogenous “shock” such as technological or logistic improvements may, under certain conditions, lead to profit reduction, while under other conditions, the profit results move in the opposite direction. This paper can be extended in future research to a case in which parameter α becomes endogenous due to costs of and efforts towards technological improvement. Such research could consider the optimal aging determination with respect to dependent variables that are discussed in this paper in addition to decision variable . This variable can be affected endogenously based on the cost functions of generating technological improvement and of marketing innovation to promote the aging process. They are combined simultaneously with aging duration and together may enable a more comprehensive and modified analysis that may be considered in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; methodology, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; validation, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; formal analysis, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; investigation, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; writing—review and editing, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; visualization, L.D.G., T.T. and U.S.; supervision, U.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Several conclusions are derived from the tables and the following algebraic discussion:

An increase in parameter represents greater benefit from the aging process and encourages its extension, i.e., shortening the time period of higher-quality wine consumption.

Improvement of the aging process (due to higher leads to an increase in the quantity of wine at any point in time.

The consumption period of wine is shorter due to an increase in parameter

The effect of an increase in parameter on the total consumption at each vintage is ambiguous. It can be either positive:

or negative:

The effect of an increase in parameter on the price of the high-quality wine is positive, as shown in Equation (A6) below.

The effect of an increase in parameter on the total profit at each vintage is ambiguous. It can be either negative:

or positive:

The reduction in the production cost due to technological improvement or reduction in the inputs price is introduced in Equation (A9).

A reduction in production cost expands the time period of consumption of higher-quality wine.

Technological improvement also increases the quantity of consumed wine at any point in time.

Technological improvement reduces the consumption period of high-quality wine. The effect of reduction in the production costs is ambiguous. It can either be positive if Equation (A12) holds or negative under Equation (A13).

For a profit maximizer winemaker, the technological improvement of the aging process encourages a larger volume of high-quality wine and thus leads to a price reduction of the wine.

As a result, the technological improvement may lead to a profit increase if Equation (A15) holds.

or to profit reduction if Equation (A16) holds.

The last discussion of the influences of independent variables on the dependent variables concerns the question of how the monopoly power that is measured by affects the decision variables. It is shown in Equation (A17).

A producer with higher monopoly power shortens the aging process.

This monopoly increases the production of high-quality wine due to higher monopoly power.

In addition, Equation (A19) holds:

The monopoly extends consumption duration based on the above Equations (A18) and (A19). The total consumption during the entire period definitely increases:

This leads to the surprising result that the price of aging wine decreases in an environment of a monopoly market, where the winemaker has significant monopoly power as obtained in Equation (A21).

The last item that is examined is the effect of monopoly power on the profits.

A winemaker that has more monopoly power desires a larger sales volume of higher production and consumption at lower prices to guarantee more profits.

References

- Avinadav, T.; Herbon, A.; Spiegel, U. Optimal inventory policy for a perishable item with demand function sensitive to price and time. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 144, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, L.; Claus, T.; Sauer, J. Literature review of deteriorating inventory models by key topics from 2012 to 2015. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 182, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek Peng, C.; Chulung, L.; Rujing, L.; Ki-Sung, H.; Anming, Z. Optimal dynamic pricing and ordering decisions for perishable products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 157, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeway, J.M.; Frey, M.L.; Lacroix, S.; Salerno, M.S. Chemical reactions in perfume ageing. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1987, 9, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turek, C.; Stintzing, F.C. Stability of Essential Oils: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, L.; Ravn, L.; Rasch, M.; Bruhn, J.B.; Christensen, A.B.; Givskov, M. Food spoilage—Interactions between food spoilage bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 78, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, L.; Liu, L.; Hu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, L. An Inventory Model for Deteriorating Drugs with Stochastic Lead Time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, W.W.; Walsh, W.J.; Symons, P.C. Modeling Battery Performance in Electric Vehicle Applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 1992, 33, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, C.A.; Bouma, A.; Meunier-Goddik, L. A decision-making tool to determine economic feasibility and break-even prices for artisan cheese operations. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 90, 8319–8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, M.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Wine Aging Technology: Fundamental Role of Wood Barrels. Foods 2020, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gil, A.; del Alamo-Sanza, M.; Sánchez-Gómez, R.; Nevares, I. Different Woods in Cooperage for Oenology: A Review. Beverages 2018, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Alamo-Sanza, M.; Nevares, I. Recent Advances in the Evaluation of the Oxygen Transfer Rate in Oak Barrels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Arenzana, L.; López-Alfaro, I.; Gutiérrez, A.R.; López, N.; Santamaría, P.; López, R. Continuous pulsed electric field treatments’ impact on the microbiota of red Tempranillo wines aged in oak barrels. Food Biosci. 2019, 27, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Dipalmo, T.; Rizzello, C.G.; Corbo, F.; Crupi, P. Emerging technology to develop novel red winemaking practices: An overview. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 38, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Montalvo, F.J.F.; Cámara, E.M.; de la Parte, M.M.P.; Jiménez-Macías, E.; Blanco-Fernández, J. Economic-environmental impact analysis of alternative systems for red wine ageing in re-used barrels. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata, A. Red Wine Technology; Elsevier: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780128144008. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; García, J.F.; Sun, D.-W. Advances in Wine Aging Technologies for Enhancing Wine Quality and Accelerating Wine Aging Process. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasines-Perea, Z.; Jacquet, R.; Jourdes, M.; Quideau, S.; Teissedre, P.-L. Ellagitannins and Flavano-Ellagitannins: Red Wines Tendency in Different Areas, Barrel Origin and Ageing Time in Barrel and Bottle. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaponi, F. Il Controllo di Gestione delle Imprese Vitivinicole; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gómez, J.I.; Morini, S. An Activity-Based Costing of Wine. J. Wine Res. 2006, 17, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, L.; D’Alessio, L.; Francese, U.; Gulluscio, C.; Rossi, A. How can SMES’ winemakers know the cost of their product? Evidence from an Italian case study. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Performance Measurement and Management Control, Barcelona, Spain, 18–20 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marone, E.; Bertocci, M.; Boncinelli, F.; Marinelli, N. The cost of making wine: A Tuscan case study based on a full cost approach. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelfi, R. Evoluzione delle metodologie di analisi dei costi aziendali in relazione alle innovazioni tecniche ed organizzative. In Atti del XXXVII Convegno di Studi Sidea, Innovazione e Ricercar Nell’Agricoltura Italiana; Avenue Media: Bologna, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Torquati, B. Economia e Gestione Dell’Impresa Agraria; Edizioni Agricole: Bologna, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, V.; D’Alessio, R. Casi di Controllo di Gestione; Wolters Kluwer: Milano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eustis, R.H. System for Non-Deleterious Accelerated Aging of Wine or Spirits. US Patent 11/856,893, 23 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovic, G.; Jeromel, A.; Maslov, L.; Pollnitz, A.; Orlić, S. Use of acacia barrique barrels—Influence on the quality of Malvazija from Istria wines. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.D.; Panighel, A.; Vedova, A.D.; Stella, L.; Flamini, R. Changes in chemical composition of a red wine aged in acacia, cherry, chestnut, mulberry, and oak wood barrels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Mateus, A.M.; Belchior, A.P. Flavour and odour profile modifications during the first five years of Lourinhã brandy maturation on different wooden barrels. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 563, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Capuano, R.; Lisanti, M.T.; Strollo, D.; Moio, L. Effect of aging in new oak, one-year-used oak, chestnut barrels and bottle on color, henolics and gustative profile of three monovarietal red wines. Eur. Food Res. Sci. 2010, 231, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simón, B.F.; Cadahía, E.; Jalocha, J. Volatile compounds in a Spanish red wine aged in barrels made of Spanish, French, and American oak wood. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7671–7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Simón, B.F.; Cadahía, E.; Sanz, M.; Poveda, P.; Perez-Magariño, S.; Ortega-Heras, M.; González-Huerta, C. Volatile compounds and sensorial characterization of wines from four Spanish denominations of origin, aged in Spanish Rebollo (Quercus pyrenaica Willd.) oak wood barrels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9046–9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Simón, B.F.; Hernández, T.; Cadahía, E.; Dueñas, M.; Estrella, I. Phenolic compounds in a Spanish red wine aged in barrels made of Spanish, French and American oak wood. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003, 216, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, E.D.; Mejías, R.C.; Marín, R.N.; Bejarano, M.J.R.; Dodero, M.C.R.; Barroso, C.G. Accelerated aging of a Sherry wine vinegar on an industrial scale employing microoxygenation and oak chips. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 232, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartini, E.; Arfelli, G.; Fabiani, A.; Piva, A. Influence of chips, lees and micro-oxygenation during aging on the phenolic composition of a red Sangiovese wine. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1599–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja-Soares, J.; Roque, R.; Cabrita, M.J.; Anjos, O.; Belchior, A.P.; Caldeira, I.; Canas, S. Effect of innovative technology using staves and micro-oxygenation on the odorant and sensory profile of aged wine spirit. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Ortín, A.B.; Lencina, A.G.; Cano-López, M.; Pardo-Mínguez, F.; López-Roca, J.M.; Gómez-Plaza, E. The use of oak chips during the ageing of a red wine in stainless steel tanks or used barrels: Effect of the contact time and size of the oak chips on aroma compounds. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2008, 14, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.L.; Benitez, B.; Troncoso, A.M. Accelerated aging of wine vinegars with oak chips: Evaluation of wood flavour compounds. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Heras, M.; Pérez-Magariño, S.; Cano-Mozo, E.; González-San José, M.L. Differences in the phenolic composition and sensory profile between red wines aged in oak barrels and wines aged with oak chips. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.C.; Chen, F.C. The application of 20 kHz ultrasonic waves to accelerate the aging of different wines. Food Chem. 2002, 79, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, C.G.; Morabito, J.A. Wine Aging Method and System. US Patent 11/043,121, 22 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ancín-Azpilicueta, C.; González-Marco, A.; Jiménez-Moreno, N. Evolution of esters in aged Chardonnay wines obtained with different vinification methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 2446–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segade, S.R.; Vázquez, E.S.; Rodríguez, E.V.; Martínez, J.R. Influence of training system on chromatic characteristics and phenolic composition in red wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 229, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernanz, D.; Gallo, V.; Recamales, Á.F.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; González-Miret, M.L.; Heredia, F.J. Effect of storage on the phenolic content, volatile composition and colour of white wines from the varieties Zalema and Colombard. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Marsellés-Fontanet, A.R.; Arias-Gil, M.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C.; Martín-Belloso, O. Effect of storage conditions on the volatile composition of wines obtained from must stabilized by PEF during ageing without SO2. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2008, 9, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.; Kotseridis, Y.; Brindle, I.D.; Inglis, D.; Pickering, G.J. Effect of light and temperature on 3-alkyl-2-methoxypyrazine concentration and other impact odourants of Riesling and Cabernet Franc wine during bottle ageing. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, P.; Castro, R.; García Barroso, C. Changes in the polyphenolic and volatile contents of “fino” sherry wine exposed to ultraviolet and visible radiation during storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6482–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, M.; Emanuele, L.; Racioppi, R. The effect of heat and light on the composition of some volatile compounds in wine. Food Chem. 2009, 117, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, A.; Puig, J.; Lladoa, N.; Zamora, F. Sealing and storage position effects on wine evolution. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillé, S.; Samson, A.; Wirth, J.; Diéval, J.B.; Vidal, S.; Cheynier, V. Sensory characteristics changes of red Grenache wines submitted to different oxygen exposures pre and post bottling. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2010, 660, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinadav, T.; Herbon, A.; Spiegel, U. Optimal ordering and pricing policy for demand functions that are separable into price and inventory age. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 155, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerine, M.; Winkler, M. Composition and quality of musts and wines of California grapes. Hilgardia 1944, 15, 493–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstones, J. Viticulture and Environment; Winetitles: Underdale, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter, O. Why we do it. Liquid Assets 1986, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter, O. Objective vintage charts: Red Bordeaux and California Cabernet Sauvignon. Liquid Assets 1987, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter, O. Vintage advice: Is 1986 another outstanding Bordeaux vintage? (No! And you heard it here first). Liquid Assets 1987, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter, O. Just how good are wine writers’ predictions? (Surprise! The recent vintages are rated highest!). Liquid Assets 1990, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.V.; Storchmann, K. Wine market prices and investment under uncertainty: An econometric model for Bordeaux crus classés. Agric. Econ. 2001, 26, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chevet, J.-M.; Lecocq, S.; Visser, M. Climate, grapevine phenology, wine production, and prices: Pauillac (1800–2009). Am. Econ. Rev. Pap. Proc. 2011, 101, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ashenfelter, O.; Storchmann, K. Using a hedonic model of solar radiation to assess the economic effect of climate change: The case of Mosel valley vineyards. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2010, 92, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadeddu, L.; Cauli, A. Wine and maths: Mathematical solutions to wine-inspired problems. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 49, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, S. Mathematics and wine. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 192, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenfelter, O. Predicting the prices and quality of Bordeaux wines. Econ. J. 2008, 118, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenfelter, O.; Ashmore, D.; Lalonde, R. Bordeaux wine vintage quality and the weather. Chance 1995, 8, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenfelter, O. Fine wine trading tips: California Cabernet wine-aging mutual find. Liquid Assets 1987, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Haeger, J.W.; Storchmann, K. Prices of American pinot noir wines: Climate, craftsmanship, critics. Agric. Econ. 2006, 35, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.; Anderson, K. What determines the future value of an icon wine? New evidence from Australia. J. Wine Econ. 2006, 1, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasker, W.S. The rate of return to storing wines. J. Polit. Econ. 1979, 87, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, E. To save or savor: The rate of return to storing wine. J. Polit. Econ. 1981, 89, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R. Do Not Invest in Wine, at Least in the U.S., unless You Plan to Drink it, and maybe Not even then. Or: As an Investment Wine is a no Corker; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, B.J.; Jacobsen, J.P. The rate of return on investment in wine. Econ. Inq. 2001, 39, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, J.J. Wine investment and portfolio diversification gains. J. Wine Econ. 2010, 5, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masset, P.; Henderson, C. Wine as an alternative asset class. J. Wine Econ. 2010, 5, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masset, P.; Weisskopf, J.-P. Raise Your Glass: Wine Investment and the Financial Crisis; AAWE Working Paper No. 57.; American Association of Wine Economists: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhue, R.E.; LaFrance, J.T.; Simon, L.K. Wine Taxes, Production, Aging and Quality. J. Wine Econ. 2009, 4, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, S.; Pecotich, A. Evaluation of wine by expert and novice consumers in the presence of variations in quality, brand and country of origin cues. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfer, H.; Nelson, J.; Ebeler, S.E.; Heymann, H. Correlating wine quality indicators to chemical and sensory measurements. Molecules 2015, 20, 8453–8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, F.S.; Cacho, J.; Ferreira, V.; Escudero, A. Aroma chemical composition of red wines from different price categories and its relationship to quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5045–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Heras, M.; González-Sanjosé, M.L.; González-Huerta, C. Consideration of the influence of aging process, type of wine and oenological classic parameters on the levels of wood volatile compounds present in red wines. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urkude, R.; Dhurvey, V.; Kochhar, S. Pesticide residues in beverages. In Quality Control in the Beverage Industry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 529–560. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, S.; Silva, F.V. Preservatives and Preservation Approaches in Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 203–235. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).