The Relationship between Government Information Supply and Public Information Demand in the Early Stage of COVID-19 in China—An Empirical Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

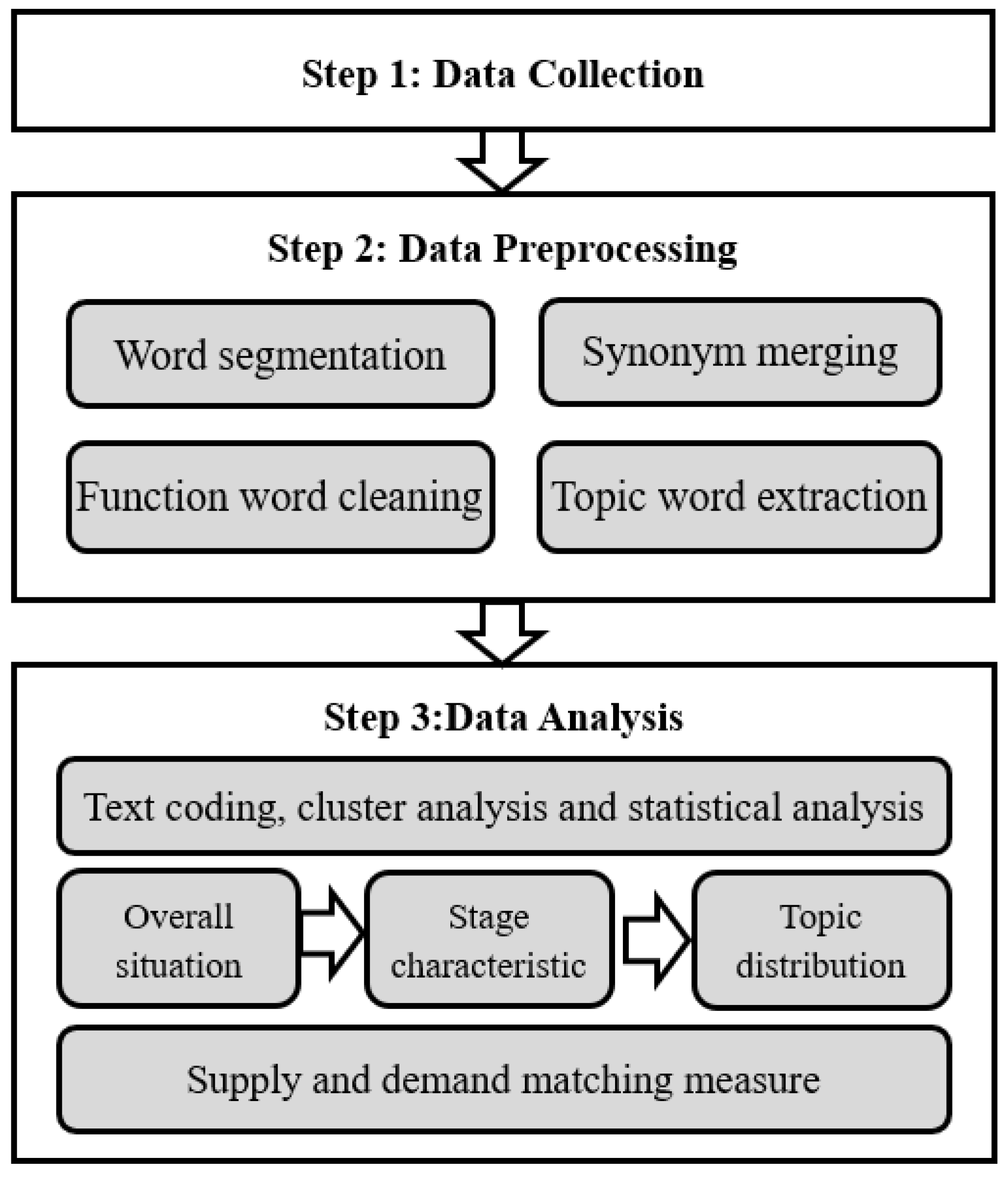

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

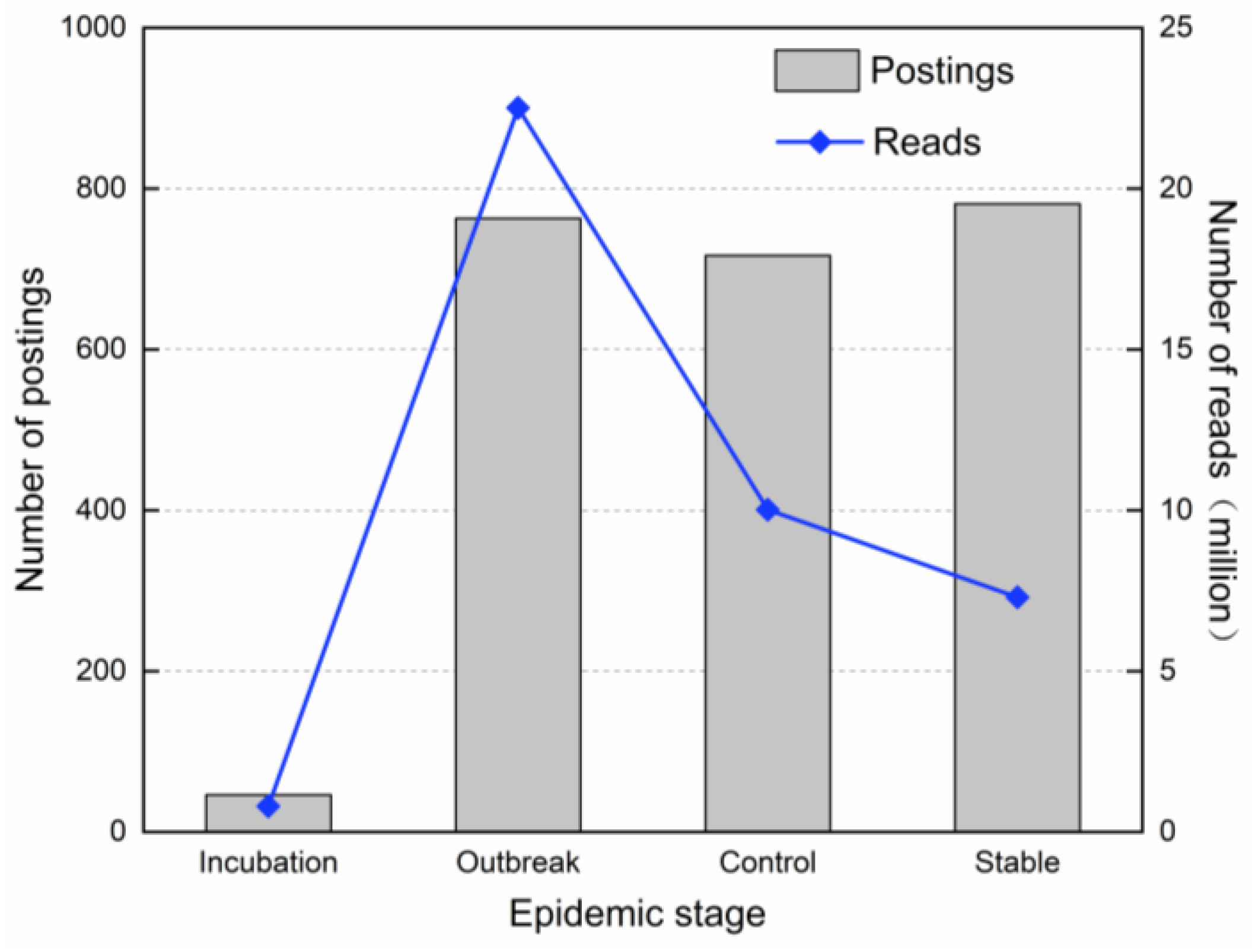

3.1. Overall Situation

3.2. Stage Characteristics

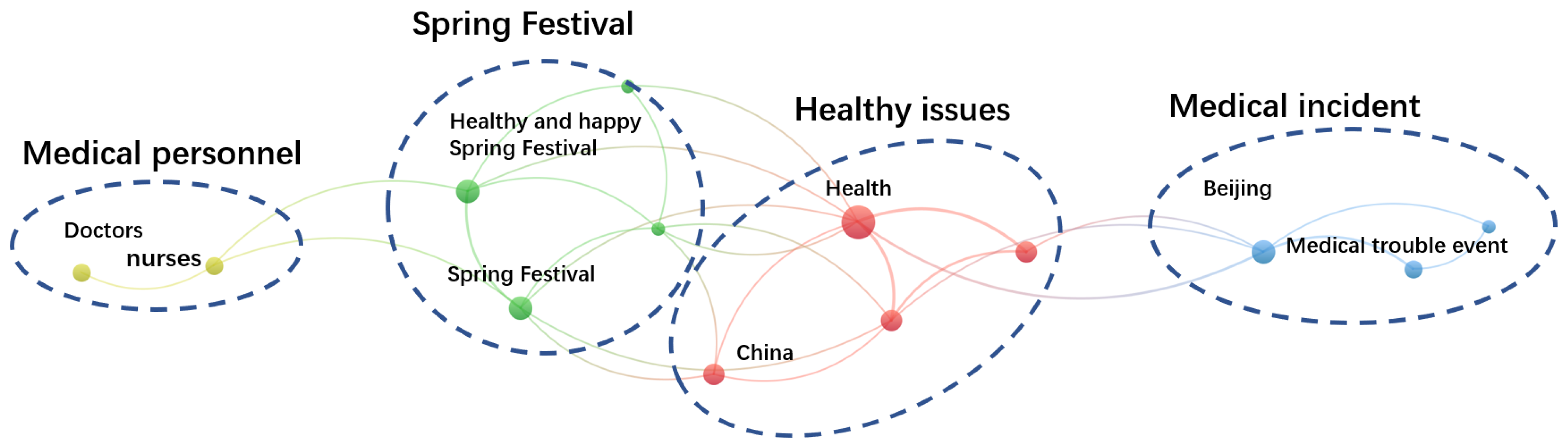

3.2.1. Incubation Stage

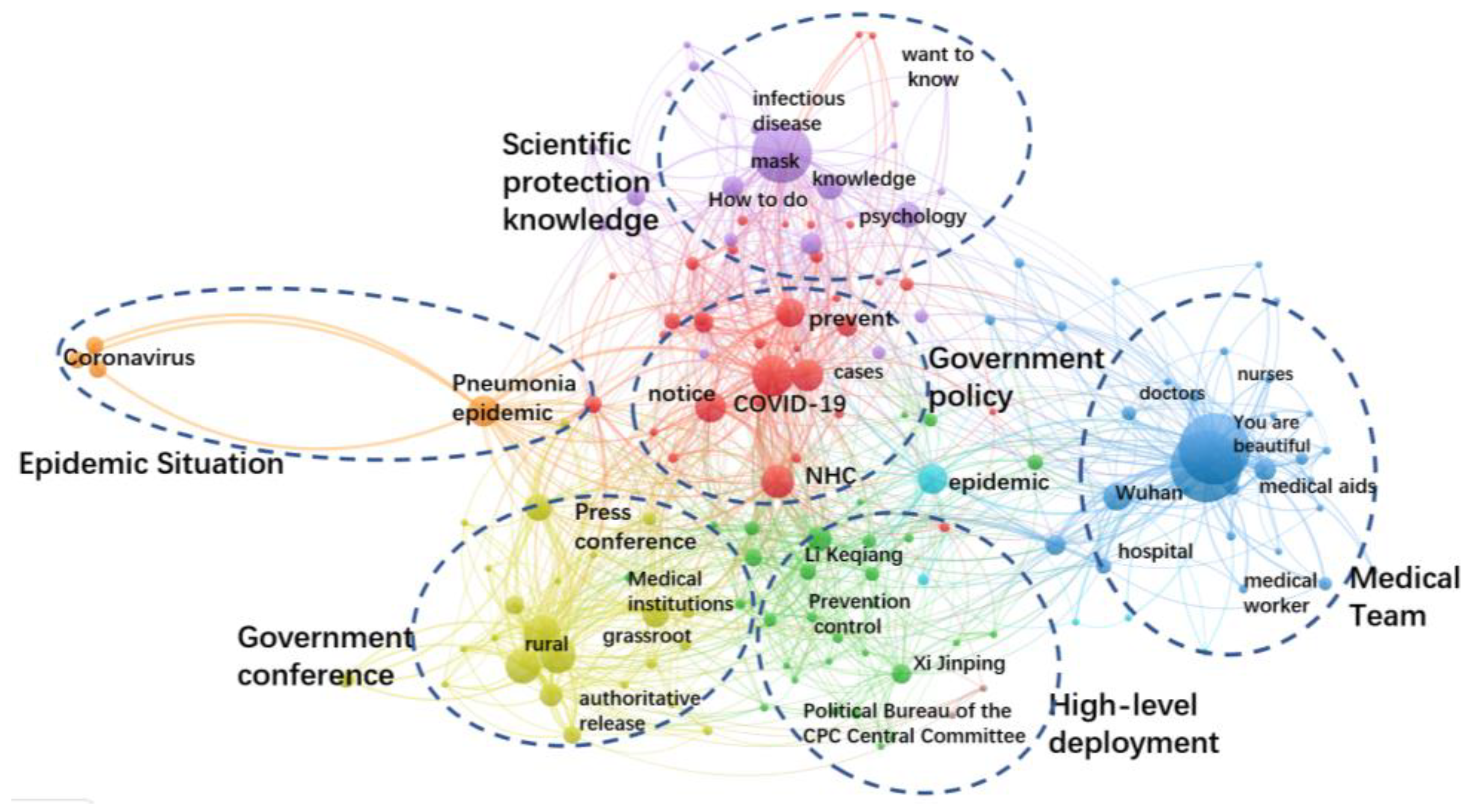

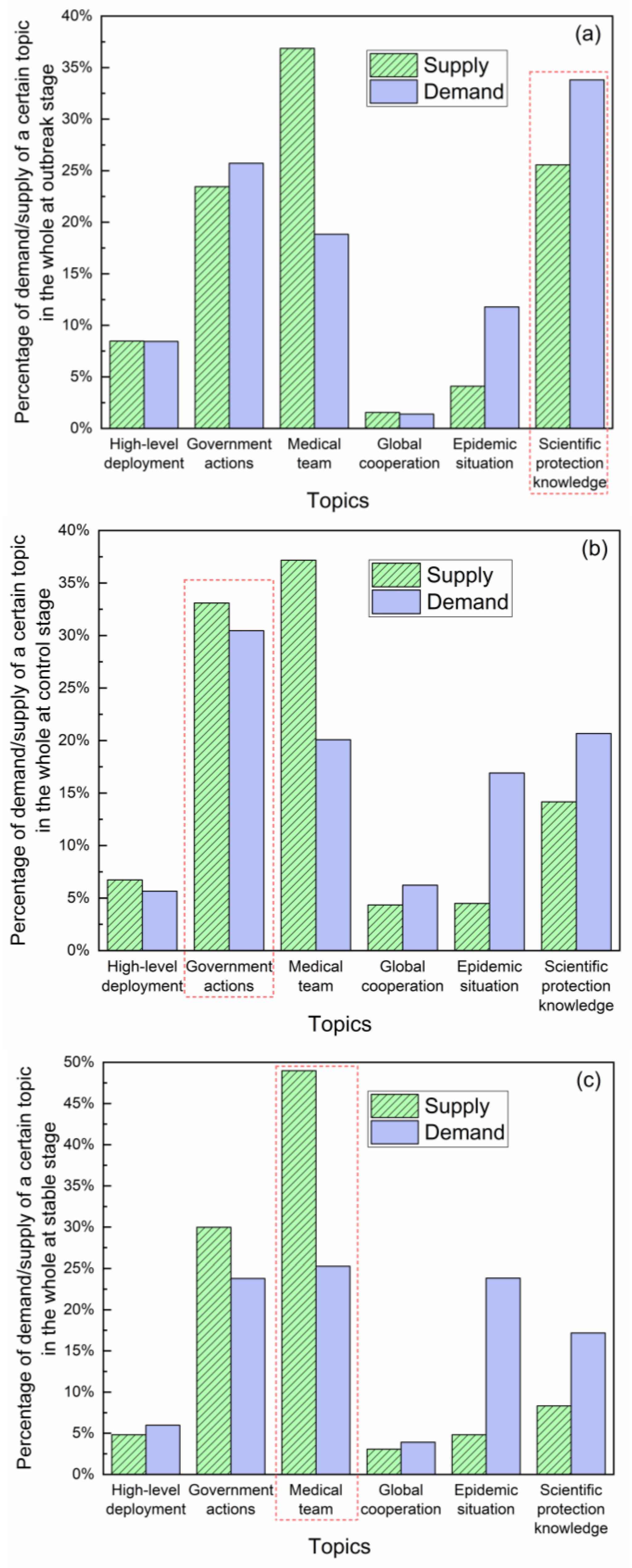

3.2.2. Outbreak Stage

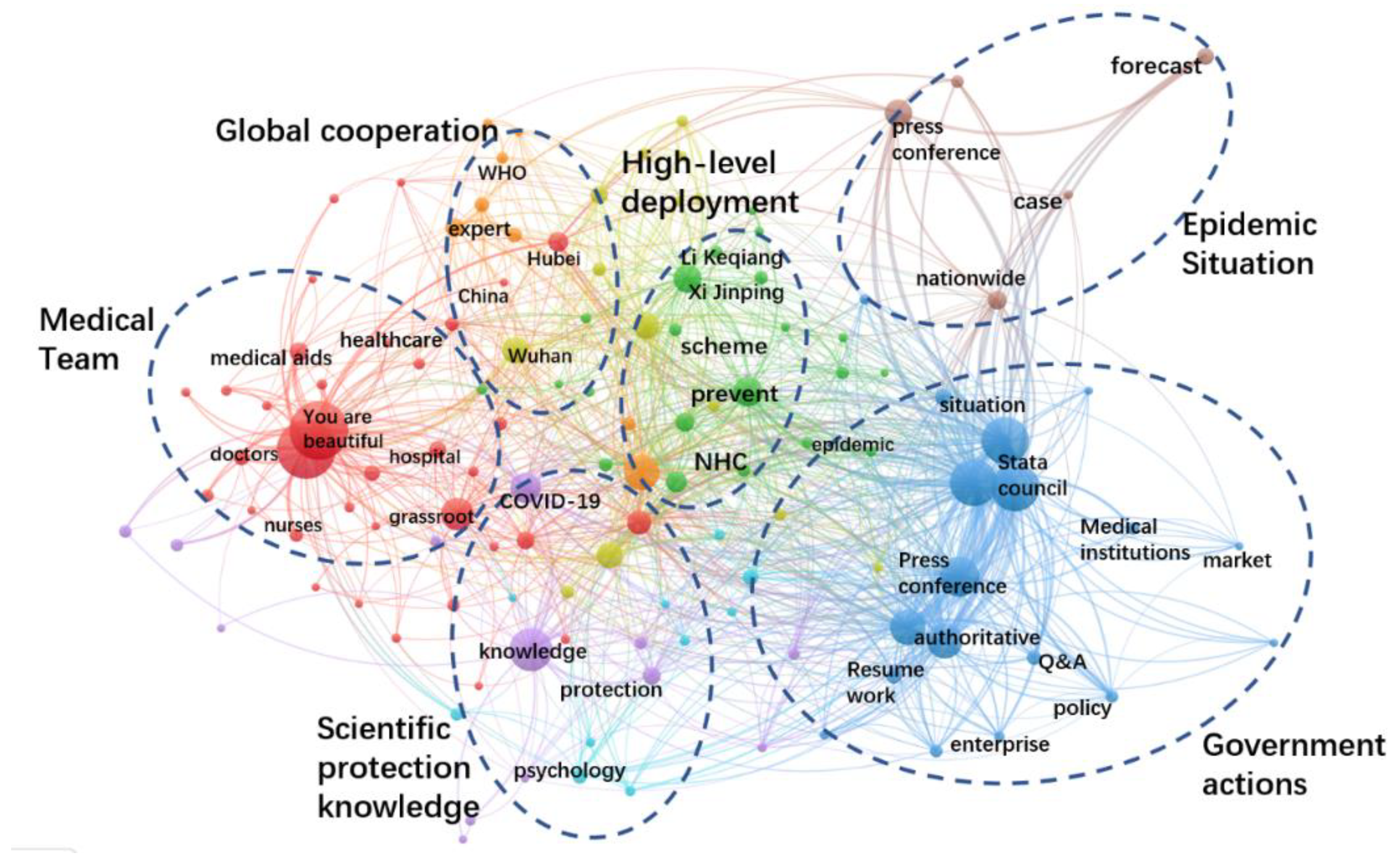

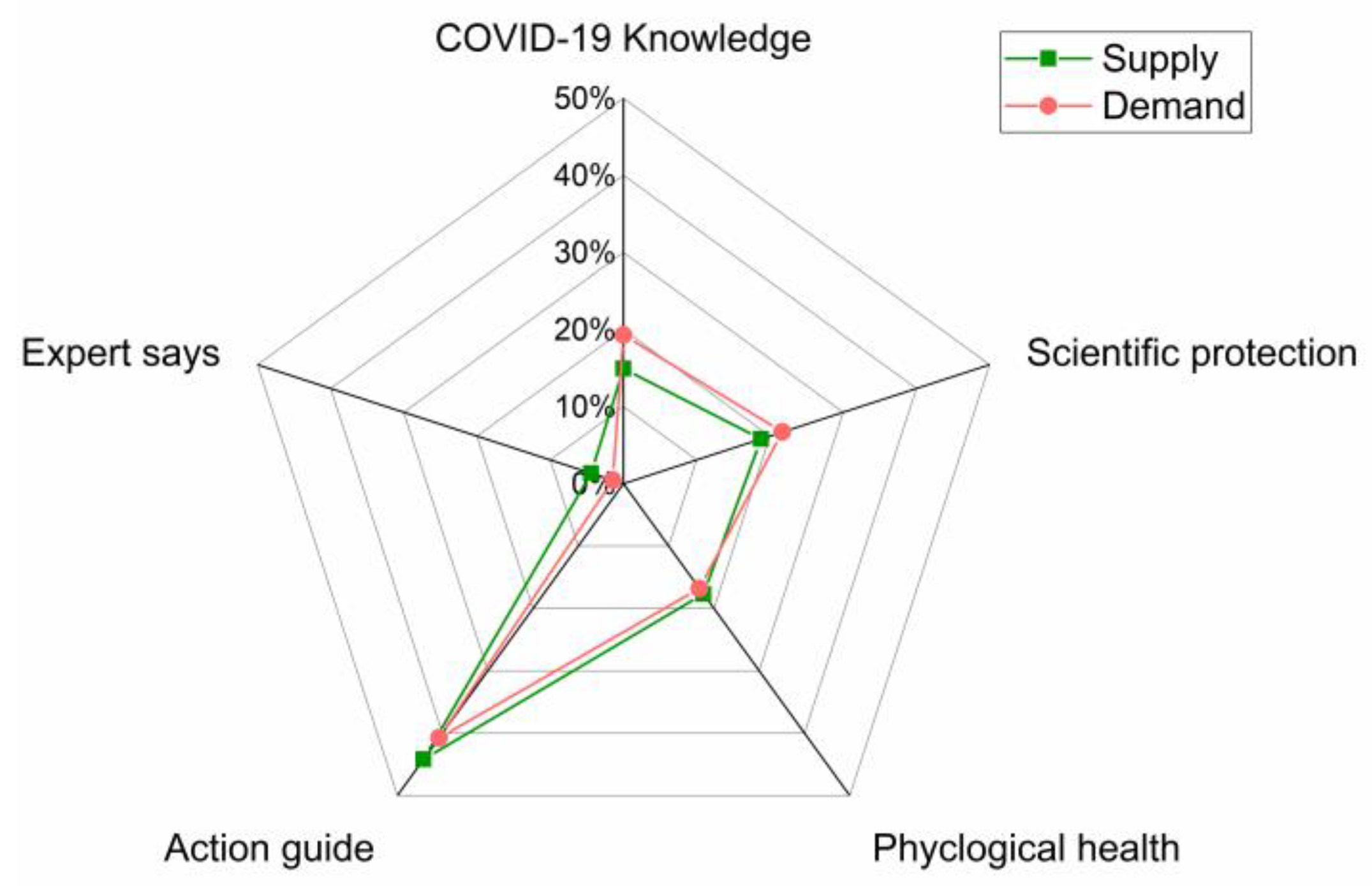

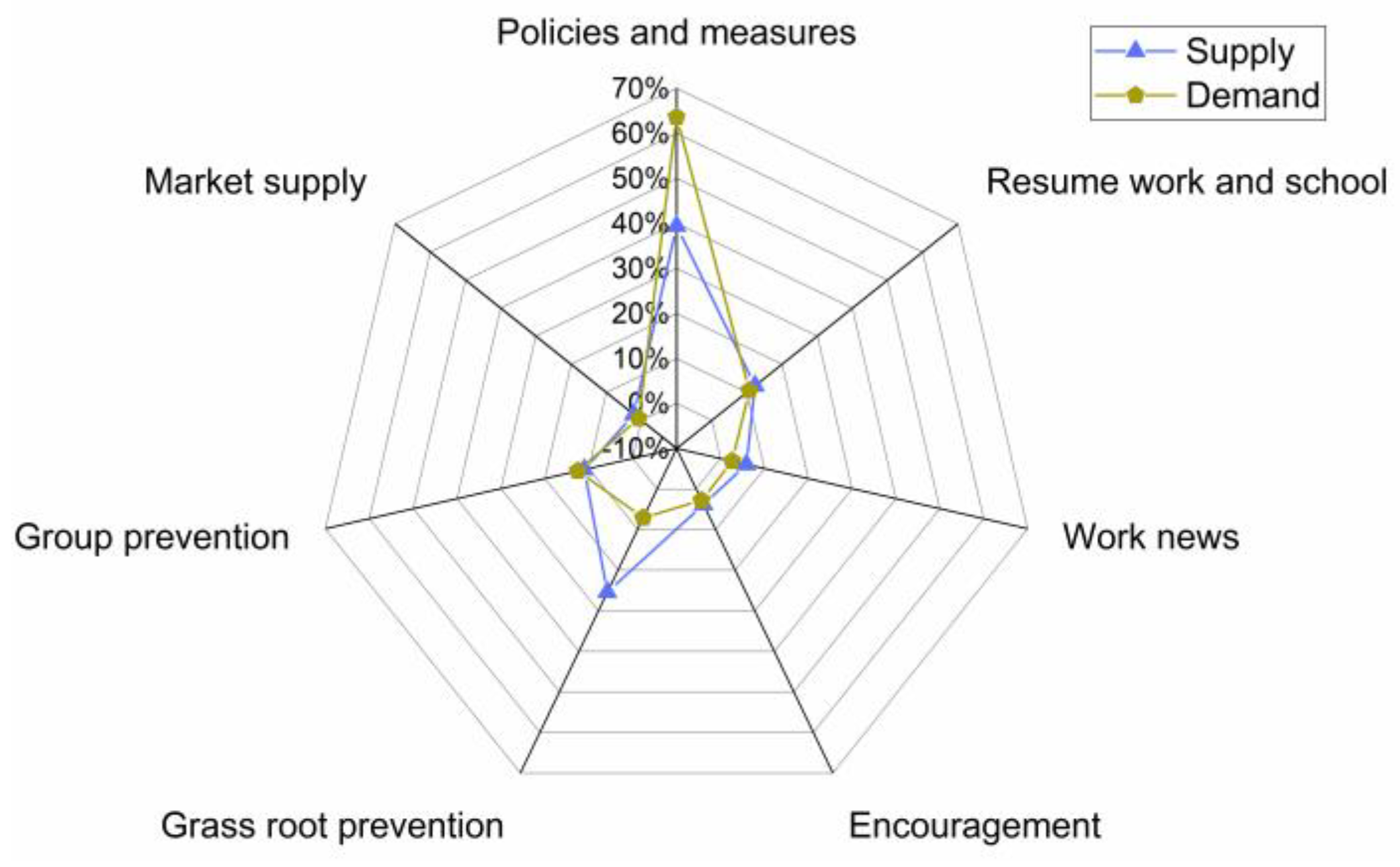

3.2.3. Control Stage

3.2.4. Stable Stage

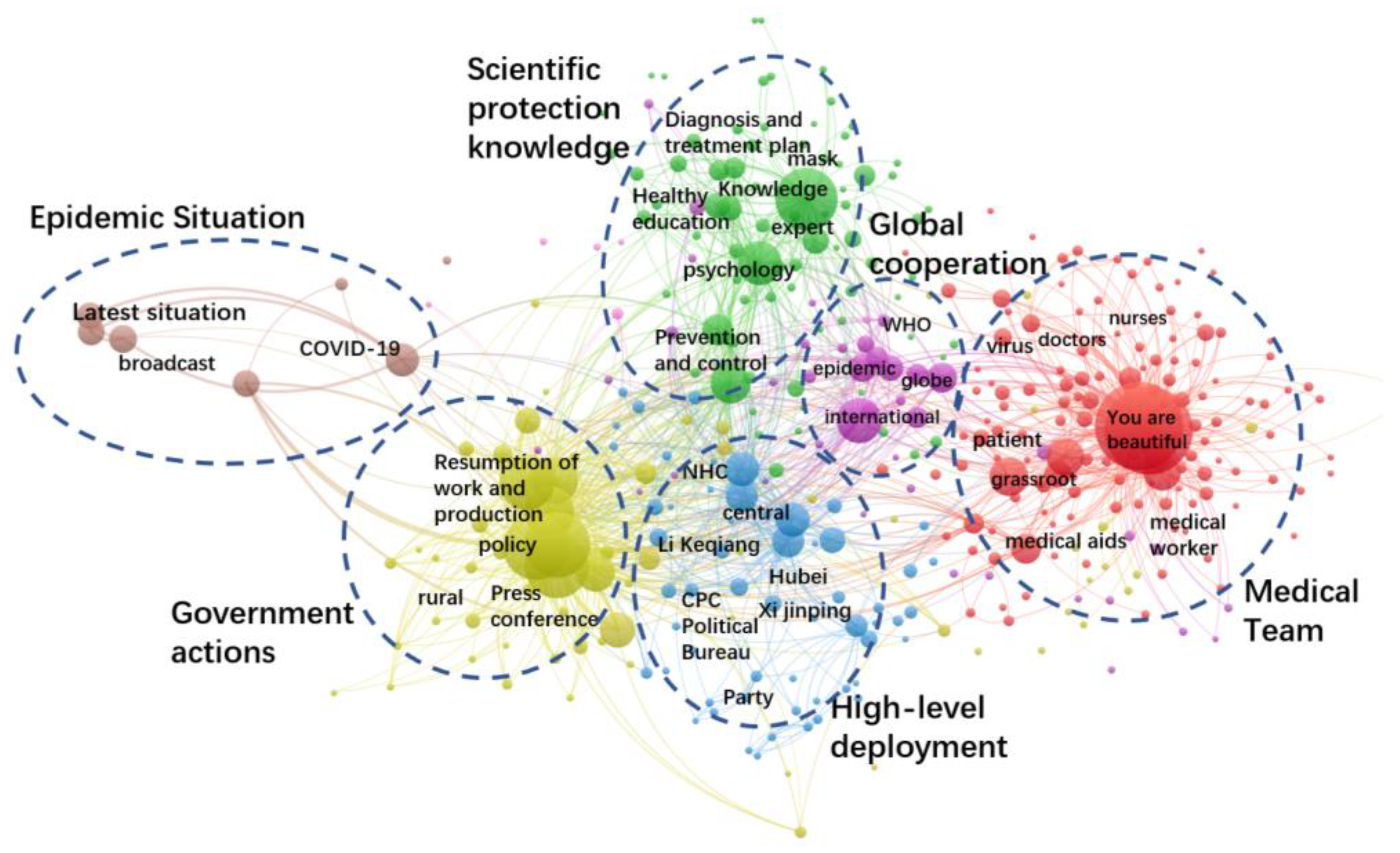

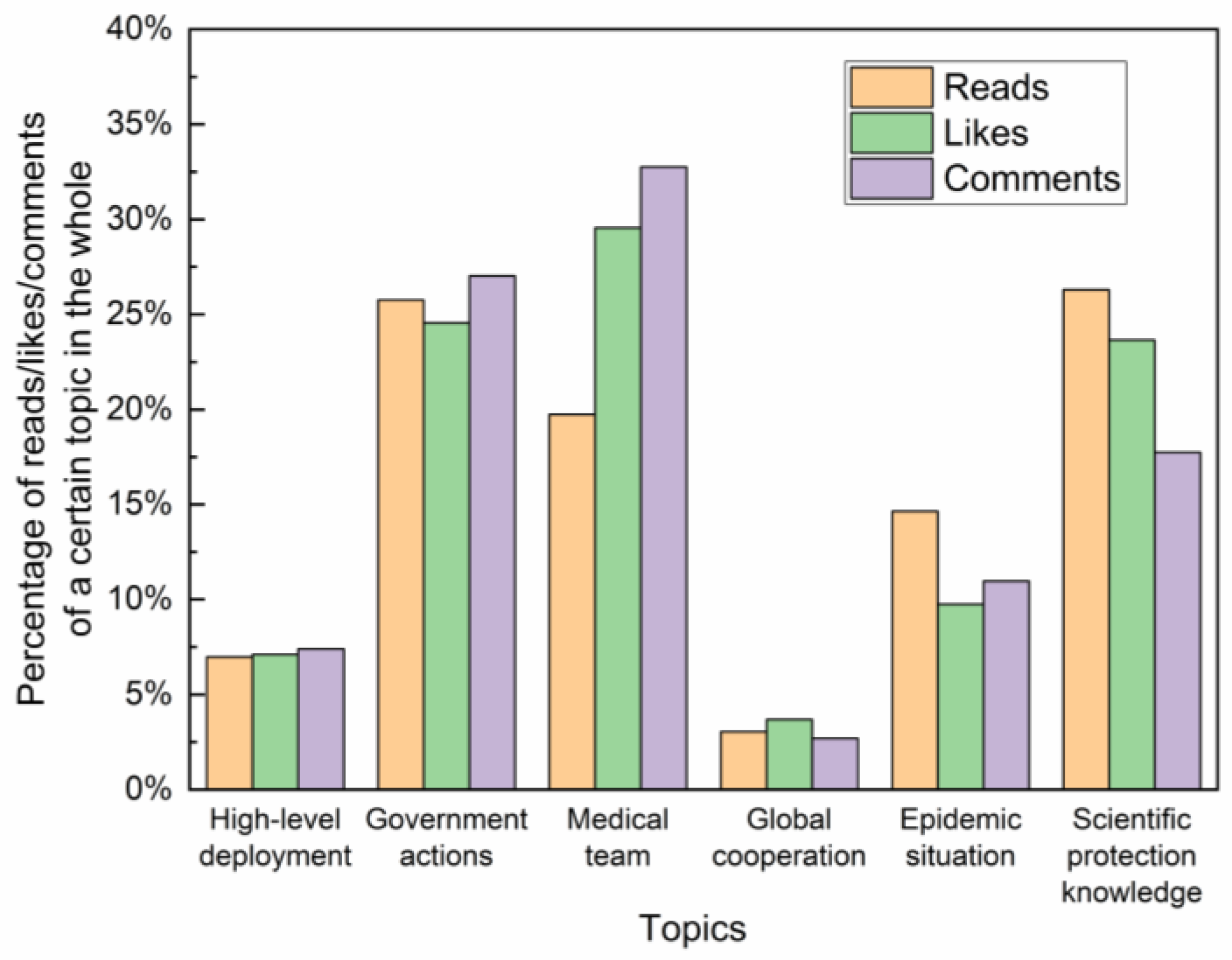

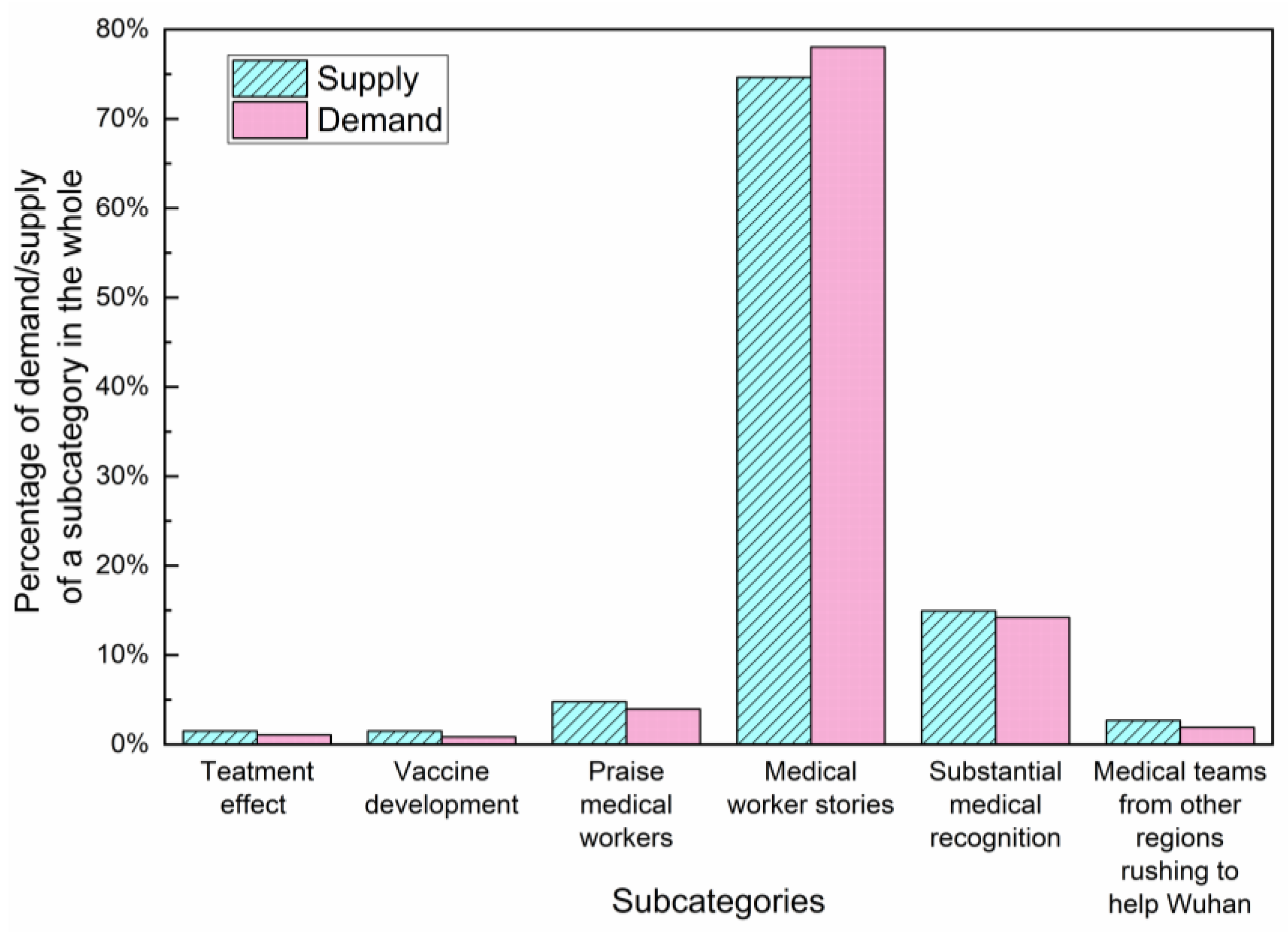

3.3. Topic Distribution Characteristics

3.3.1. “Scientific Protection Knowledge” in the Outbreak Stage

3.3.2. “Government Actions” in Control Stage

3.3.3. “Medical Teams” in Stable Stage

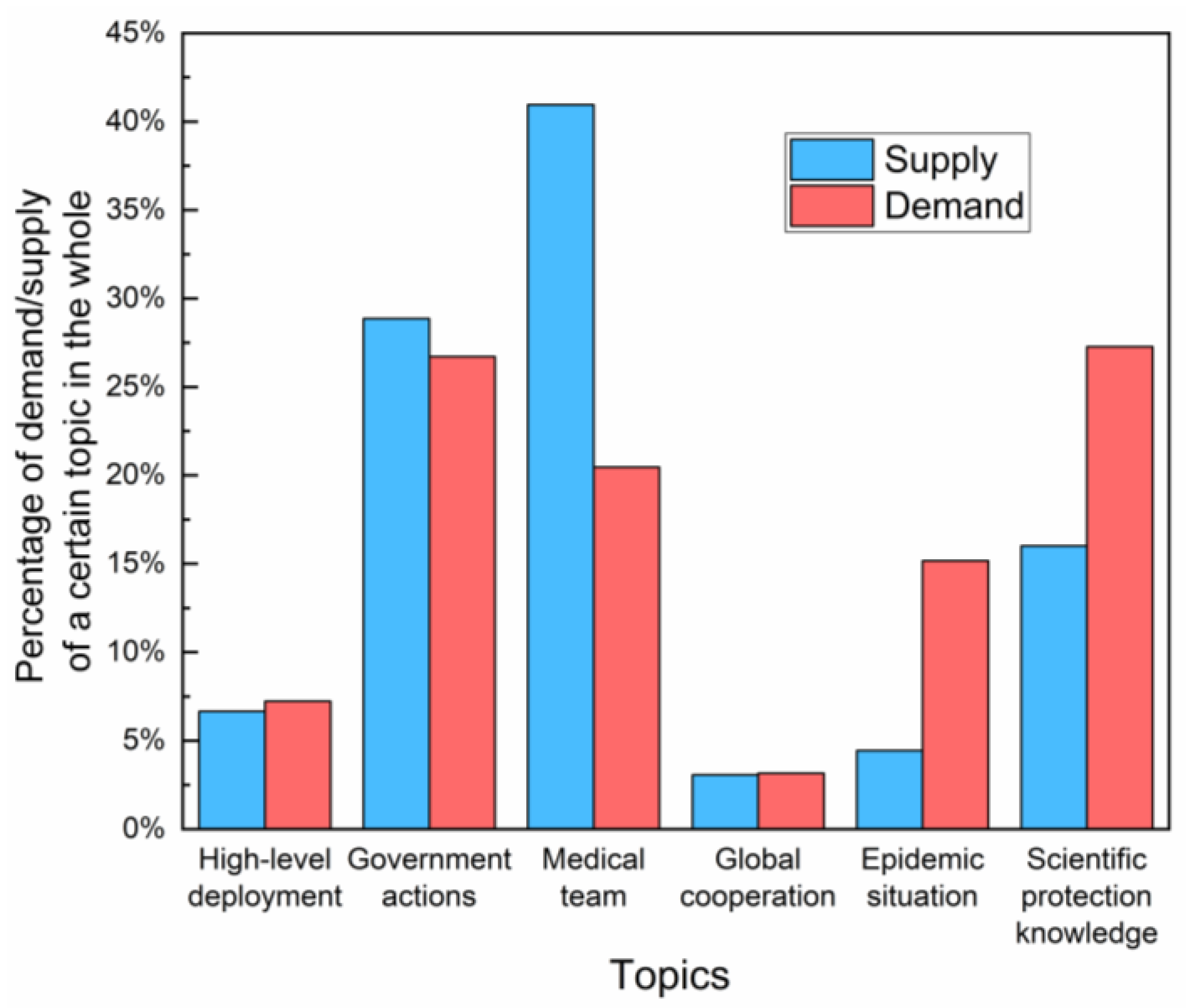

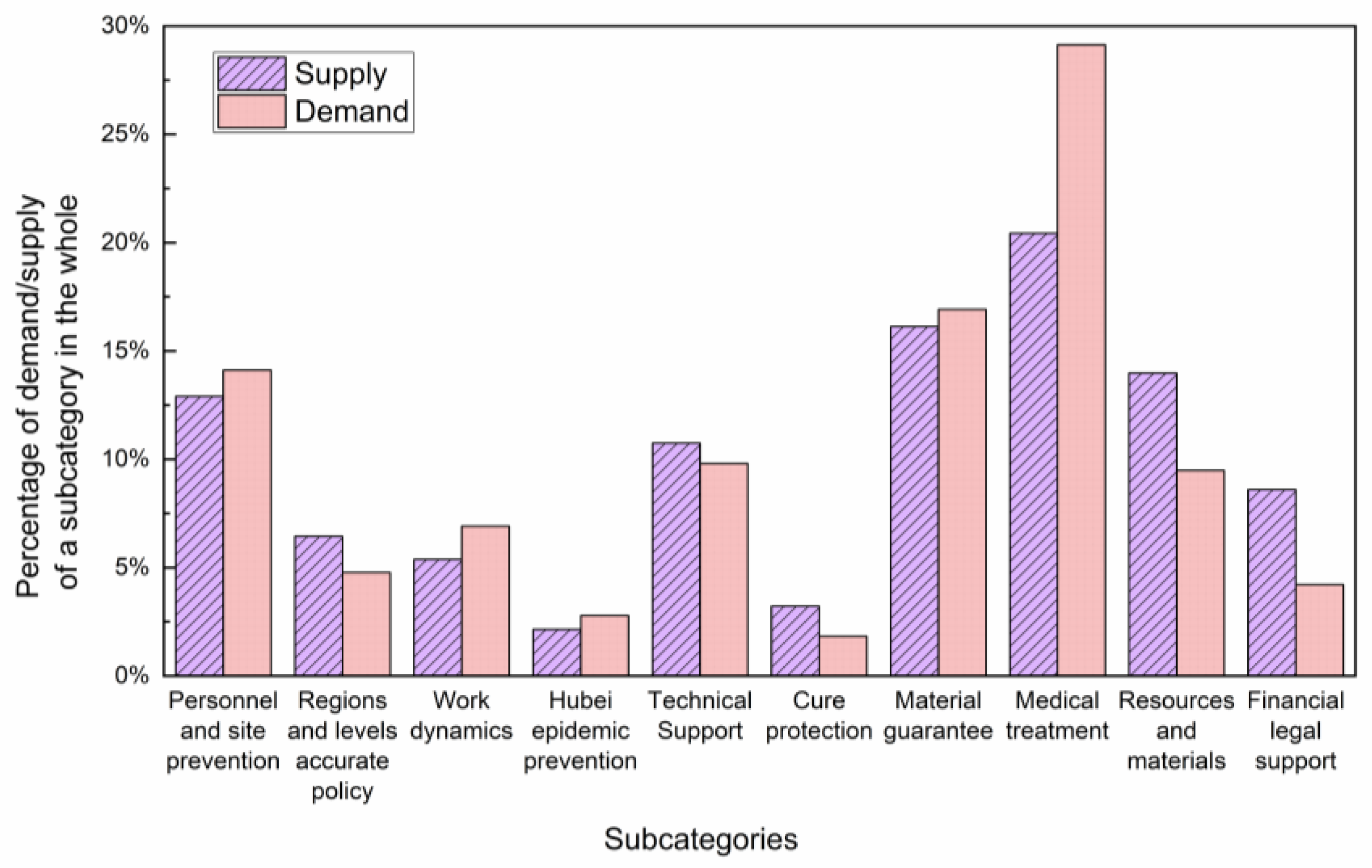

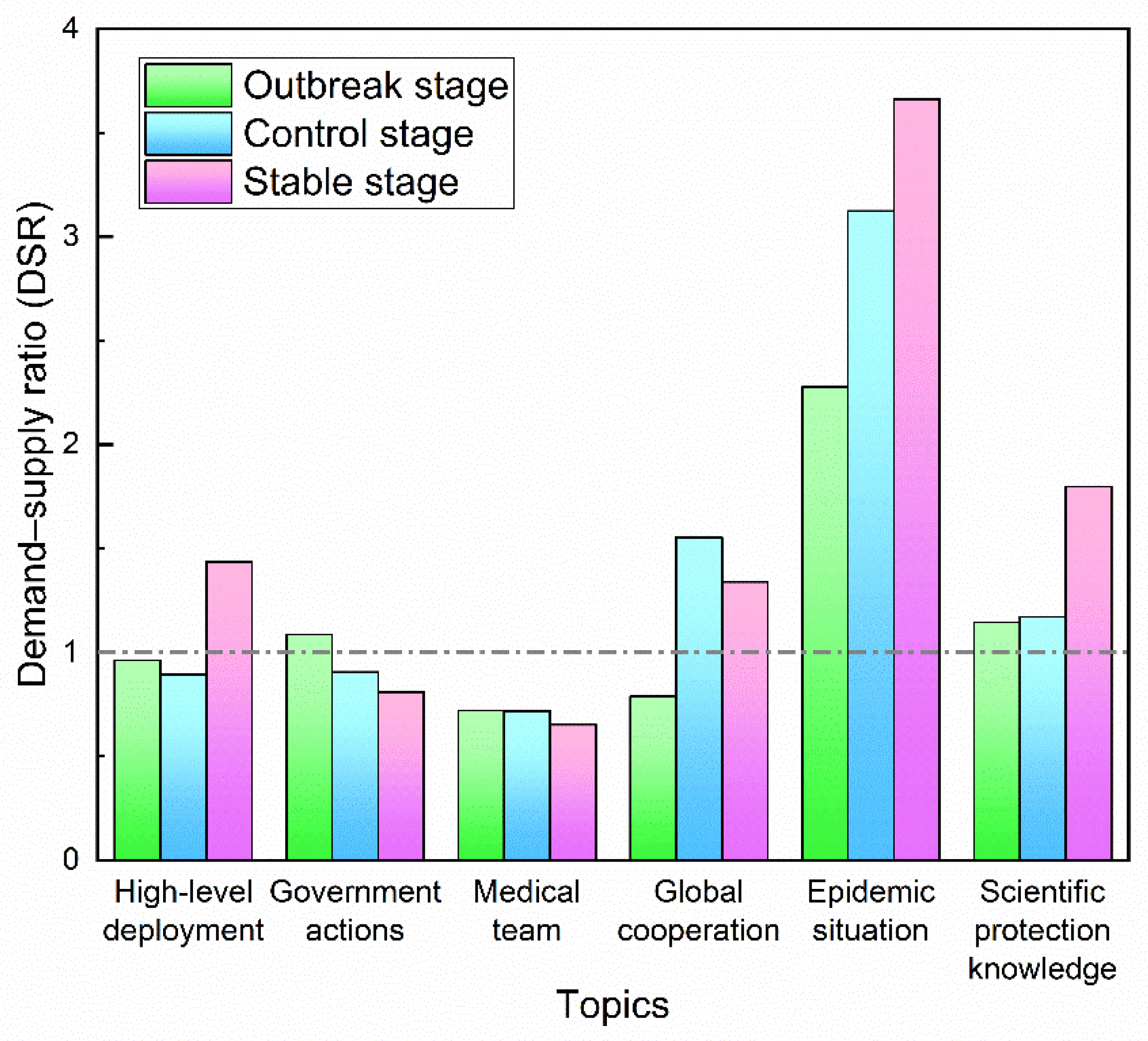

3.4. Measure of Demand–Supply Ratio

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Text Coding Results

| Categories | Sub-Topics | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| High-level deployment | High-level deployment | Speeches and various instructions of China’s top leaders on the deployment of epidemic prevention and control. |

| Government actions | Policies and measures | Policies, measures and interpretations of epidemic prevention and control, including site measures, traffic measures, technical support, material support, market dynamics, etc. |

| Resume work and school | Information about the resumption of work, production and schools in the middle and later stages of the epidemic. | |

| Work news | The NHC updated its epidemic prevention and control work, etc. | |

| Encouragement | Boost the morale of epidemic prevention and control through letters, speeches, songs, videos and other forms. | |

| Grass root prevention | Actions of urban community, rural and other grass-roots units in epidemic prevention and control, etc. | |

| Group prevention | Preventing suggestions for special groups such as the elderly, rural people, pregnant women and children, etc. | |

| Market supply | Material resources guarantee and market conditions during the epidemic period, etc. | |

| Professional prevention and control plan | The professional prevention and control plan was formulated and issued by the State Council of China to guide the epidemic prevention and control work of local governments, etc. | |

| Medical team | Medical teams from other regions rush to help Wuhan | Medical teams from all over China rushed to Wuhan to provide medical assistance during the most severe period of epidemic prevention and control. |

| Medical guide | Guidelines issued by various localities to facilitate people’s medical treatment. | |

| Safeguard measures for medical staff | Measures to protect the safety and health of front-line medical staff | |

| Amy’s aid | The CPC Central Military Commission sent medical staff to Wuhan for medical assistance | |

| Substantial medical recognition | The list of people who went to Hubei for medical assistance from all over the country, and the people on the list will be rewarded substantively. | |

| Medical worker stories | Touching stories of a wide variety of medical workers at all levels and places during the COVID-19 | |

| Praise medical workers | Praise and salute the medical staff through language, painting, photography and other forms. | |

| Vaccine development | Vaccine and drug development in response to COVID-19. | |

| Epidemic judgement | Epidemic judgment released at the press conference of the joint prevention and control mechanism of the State Council. | |

| Diagnosis and treatment plan | Notification and interpretation of the diagnosis and treatment plan for the issuance of COVID-19 | |

| Treatment effect | Cure and treatment effect of COVID-19. | |

| Global cooperation | Global cooperation | Active international exchanges and cooperation on fighting COVID-19 that conducted by Chinese government. |

| Epidemic situation | Epidemic situation | Daily broadcast of the latest epidemic situation of COVID-19 in China. |

| Scientific protection knowledge | Introduction of coronavirus | Knowledge and introduction of new coronavirus. |

| Scientific protection | How to carry out scientific protection? Government publishes related knowledge. | |

| Phycological health | Knowledge of mental health, how to overcome bad emotions, debug mental state, deal with psychological pressure, etc. | |

| Action guide | Appropriate behavioral guidelines for dealing with COVID-19, including personal protection guidelines for traffic behavior, home behavior, etc. | |

| Expert says | The voice of medical experts, such as academician Zhong Nanshan, Academician Li Lanjuan, etc. |

Appendix B. DSR and Topic Distribution at Different Stages

References

- COVID-19 Map—John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Liao, Q.; Yuan, J.; Dong, M.; Yang, L.; Fielding, R.; Lam, W.W.T. Public engagement and government responsiveness in the communications about COVID-19 during the early epidemic stage in china: Infodemiology study on social media data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islm, T.; Meng, H.; Pitafi, A.H.; Ullah Zafar, A.; Sheikh, Z.; Shujaat Mubarik, M.; Liang, X. Why DO citizens engage in government social media accounts during COVID-19 pandemic? A comparative study. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 62, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. Social media institutionalization in the U.S. federal government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. An interplay model for rumour spreading and emergency development. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2009, 388, 4159–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Sattar, U. Conceptualizing COVID-19 and public panic with the moderating role of media use and uncertainty in china: An empirical framework. Healthcare 2020, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J. E-Participation, transparency, and trust in local government. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbeck, J.; Grimes, J.M.; Rogers, A. Twitter use by the U.S. congress. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeemering, E.S. Functional fragmentation in city hall and Twitter communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Atlanta, San Francisco, and Washington, DC. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.D.; Kreps, G.L. An analysis of government communication in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recommendations for effective government health risk communication. World Med. Health Policy 2020, 12, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, H.; Platt, L.S. Examining risk and crisis communications of government agencies and stakeholders during early-stages of COVID-19 on Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland-Wood, B.; Gardner, J.; Leask, J.; Ecker, U.K.H. Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.A.; Can, S.H. Linguistic analysis of municipal twitter feeds: Factors influencing frequency and engagement. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Guan, X. The governance strategies for public emergencies on social media and their effects: A case study based on the microblog data. Electron. Mark. 2016, 26, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L.; Lengel, R.H.; Trevino, L.K. Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: Implications for information systems. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1987, 11, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. The social media innovation challenge in the public sector. ICT Public Adm. Democr. Coming Decad. 2013, 17, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darwish, E.B. The effectiveness of the use of social media in government communication in the UAE. J. Arab Muslim Media Res. 2017, 10, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wei, Y. Government communication effectiveness on local acceptance of nuclear power: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, W. Evaluating Crisis Communication. A 30-item Checklist for Assessing Performance during COVID-19 and Other Pandemics. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veil, S.R.; Husted, R.A. Best practices as an assessment for crisis communication. J. Commun. Manag. 2012, 16, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Luque, S.; Afanador, P.N.A.; Fernández-Rovira, C. The struggle for human attention: Between the abuse of social media and digital wellbeing. Healthcare 2020, 8, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon-Itt, S.; Skunkan, Y. Public perception of the COVID-19 pandemic on twitter: Sentiment analysis and topic modeling study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e21978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.R.; Vemprala, N.; Akello, P.; Valecha, R. Retweets of officials’ alarming vs reassuring messages during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for crisis management. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Alhuwail, D.; Househ, M.; Hai, M.; Shah, Z. Top concerns of tweeters during the COVID-19 pandemic: A surveillance study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Shi, H.; Wu, X.; Jiao, L. Sentiment analysis of rumor spread amid COVID-19: Based on weibo text. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L. Government, public, media relations and government crisis management in the New Era—Thinking triggered by the SARS incident. CASS J. Political Sci. 2003, 3, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M.S.; Hideki, N.; Yasuyuki, N. The incorporation of social media in an emergency supply and demand framework in disaster response. In Proceedings of the SocialCom 2018, Melbourne, Australia, 11–13 December 2018; pp. 1152–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S. Identifying features of related information release when facing public health emergency. Libr. Inf. 2020, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Lv, L. The application of text analysis to public management and policy research. China Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 148, 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Su, J.; Liang, C. Evolution of topics in education research: A systematic review using bibliometric analysis. Educ. Rev. 2020, 72, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uretsky, M. Planning for the inevitable crisis. Natl. Product. Rev. 1991, 10, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Z. Promoting public engagement during the COVID-19 crisis: How effective is the wuhan local government’s information release? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, J.D.; Espeleta, J.F.; Klausmeier, C.A.; Mcgroddy, M.E.; Thomas, S.A. A conceptual framework for ecosystem stoichiometry: Balancing resource supply and demand. OIKOS 2005, 109, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardenheuer, H.; Schrader, J. Supply-to-demand ratio for oxygen determines formation of adenosine by the heart. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 1986, 250, H173–H180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; An, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, X. Multiattribute supply and demand matching decision model for online-listed rental housing: An empirical study based on Shanghai. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2020, 2020, 4827503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Meng, X.; Wu, Y.; Chan, C.S.; Pang, T. Semantic matching efficiency of supply and demand texts on online technology trading platforms: Taking the electronic information of three platforms as an example. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Monge, E.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. Measuring the consumer engagement related to social media: The case of franchising. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.C.; Hasan, S.; Sadri, A.M.; Cebrian, M. Understanding the efficiency of social media based crisis communication during hurricane Sandy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wells, C.; Wang, S.; Rohe, K. Attention and amplification in the hybrid media system: The composition and activity of Donald Trump’s Twitter following during the 2016 presidential election. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 3161–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ángeles Oviedo-García, M.; Muñoz-Expósito, M.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Sancho-Mejías, M. Metric proposal for customer engagement in Facebook. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2014, 8, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Expósito, M.; Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M. How to measure engagement in Twitter: Advancing a metric. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 1122–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.R.; Guggenheim, L.; Jang, S.M.; Bae, S.Y. The dynamics of public attention: Agenda-setting theory meets big data. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, E.J. Public information officers’ social media monitoring during the Zika virus crisis, a global health threat surrounded by public uncertainty. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Saffer, A.J.; Liu, W.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Zhen, L.; Yang, A. How Public Health Agencies Break through COVID-19 Conversations: A Strategic Network Approach to Public Engagement. Health Commun. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowacki, E.M.; Lazard, A.J.; Wilcox, G.B.; Mackert, M.; Bernhardt, J.M. Identifying the public’s concerns and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s reactions during a health crisis: An analysis of a Zika live Twitter chat. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 1709–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Chen, K. Effective risk communication for public health emergency: Reflection on the COVID-19. Healthcare 2020, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yu, X.; Xu, H. Chinese public’s attention to the COVID-19 epidemic on social media: Observational descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, I.K.; Heyl, J.; Lad, N.; Facini, G.; Grout, Z. Evaluation of Twitter data for an emerging crisis: An application to the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Noh, E.B.; Choi, S.H.; Zhao, B.; Nam, E.W. Determining public opinion of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea and Japan: Social network mining on Twitter. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2020, 26, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Epidemic Stage | Timeline | Key Event |

|---|---|---|

| Incubation | 1 January to 19 January | On 20 January, expert in National Health Commission (NHC) confirmed that the virus spreads from person to person. |

| Outbreak | 20 January to 15 February | On 15 February, the press conference reported: the overall epidemic situation has become positive. |

| Control | 16 February to 6 March | On 16 February, the government deployed the resumption of work and production. |

| Stable | 7 March to 31 March | On 7 March, government started to establish strict policies to prevent imported COVID-19 cases from abroad. |

| Public Focus | Representative Postings Topics | Main Content |

|---|---|---|

| High-level meeting | 2020 National Health Work Conference held in Beijing (7 January) | The government summarized its work of 2019, studying and strengthening the construction of the health system, and deployed key tasks for 2020. |

| High-level deployment | The National Health Commission is actively carrying out the prevention and control of the pneumonia epidemic caused by the new coronavirus infection (19 January) | NHC established an epidemic response and handling leading group to guide and support Hubei Province and Wuhan City in carrying out case treatment, epidemic prevention and control and emergency response. |

| Medical incident | Sun Wenbin sentenced to death (16 January) | Outcome of the case of Sun Wenbin’s intentional homicide (medical incident) |

| Healthcare worker | To do popular science for everyone, the medical staff are really talented! (9 January) | The song “Wild Wolf Disco” was released for the medical care version of Dongguan, Guangdong, to make medical science popularization for everyone. |

| Healthcare worker | Attention, medical candidates! Register tomorrow for the 2020 National Medical Qualification Examination (8 January) | In 2020, registration matters for the medical qualification examination will be held nationwide. |

| Order | Sub-Topic | Number of Postings | Number of Reads |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical Worker Stories | 138 | 1,326,366 |

| 2 | Policies and measures | 82 | 2,745,852 |

| 3 | Action guide | 80 | 2,895,514 |

| 4 | Medical teams from other regions rush to help Wuhan | 66 | 712,263 |

| 5 | Scientific protection | 34 | 1,542,802 |

| 6 | Phycological health | 32 | 1,193,447 |

| 7 | Epidemic situation | 29 | 2,478,094 |

| 8 | Introduction of coronavirus | 27 | 1,371,355 |

| 9 | Encouragement | 23 | 459,726 |

| 10 | Praise medical workers | 23 | 438,501 |

| Order | Sub-Topic | Number of Postings | Number of Reads |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical Worker Stories | 218 | 1,069,732 |

| 2 | Policies and measures | 93 | 1,290,945 |

| 3 | Grass root prevention | 60 | 335,533 |

| 4 | Action guide | 33 | 710,056 |

| 5 | Epidemic situation | 32 | 1,677,119 |

| 6 | Global cooperation | 31 | 618,685 |

| 7 | Resume work and school | 29 | 506,190 |

| 8 | Scientific protection | 29 | 869,504 |

| 9 | Group prevention | 25 | 584,980 |

| 10 | Phycological health | 24 | 215,447 |

| Order | Sub-Topic | Number of Postings | Number of Reads |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical Worker Stories | 250 | 965,182 |

| 2 | Policies and measures | 61 | 596,512 |

| 3 | Grass root prevention | 52 | 154,172 |

| 4 | Substantial medical recognition | 49 | 334,185 |

| 5 | Resume work and school | 33 | 144,871 |

| 6 | Epidemic situation | 33 | 1,570,448 |

| 7 | Global cooperation | 21 | 2,576,53 |

| 8 | Group prevention | 18 | 274,176 |

| 9 | Scientific protection | 16 | 486,822 |

| 10 | Phycological health | 16 | 193,206 |

| Stage/Topic | High-Level Deployment | Government Actions | Medical Team | Global Cooperation | Epidemic Situation | Scientific Protection Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak | 1,772,850 | 5,406,542 | 3,959,285 | 292,337 | 2,478,094 | 7,106,485 |

| Control | 560,890 | 3,021,249 | 1,991,282 | 618,685 | 1,677,119 | 2,049,422 |

| Stable | 393,786 | 1,567,892 | 1,666,012 | 257,653 | 1,570,448 | 1,132,168 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Yu, L. The Relationship between Government Information Supply and Public Information Demand in the Early Stage of COVID-19 in China—An Empirical Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010077

Zhang T, Yu L. The Relationship between Government Information Supply and Public Information Demand in the Early Stage of COVID-19 in China—An Empirical Analysis. Healthcare. 2022; 10(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Tong, and Li Yu. 2022. "The Relationship between Government Information Supply and Public Information Demand in the Early Stage of COVID-19 in China—An Empirical Analysis" Healthcare 10, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010077

APA StyleZhang, T., & Yu, L. (2022). The Relationship between Government Information Supply and Public Information Demand in the Early Stage of COVID-19 in China—An Empirical Analysis. Healthcare, 10(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010077