Prospect Theory: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review in the Categories of Psychology in Web of Science

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

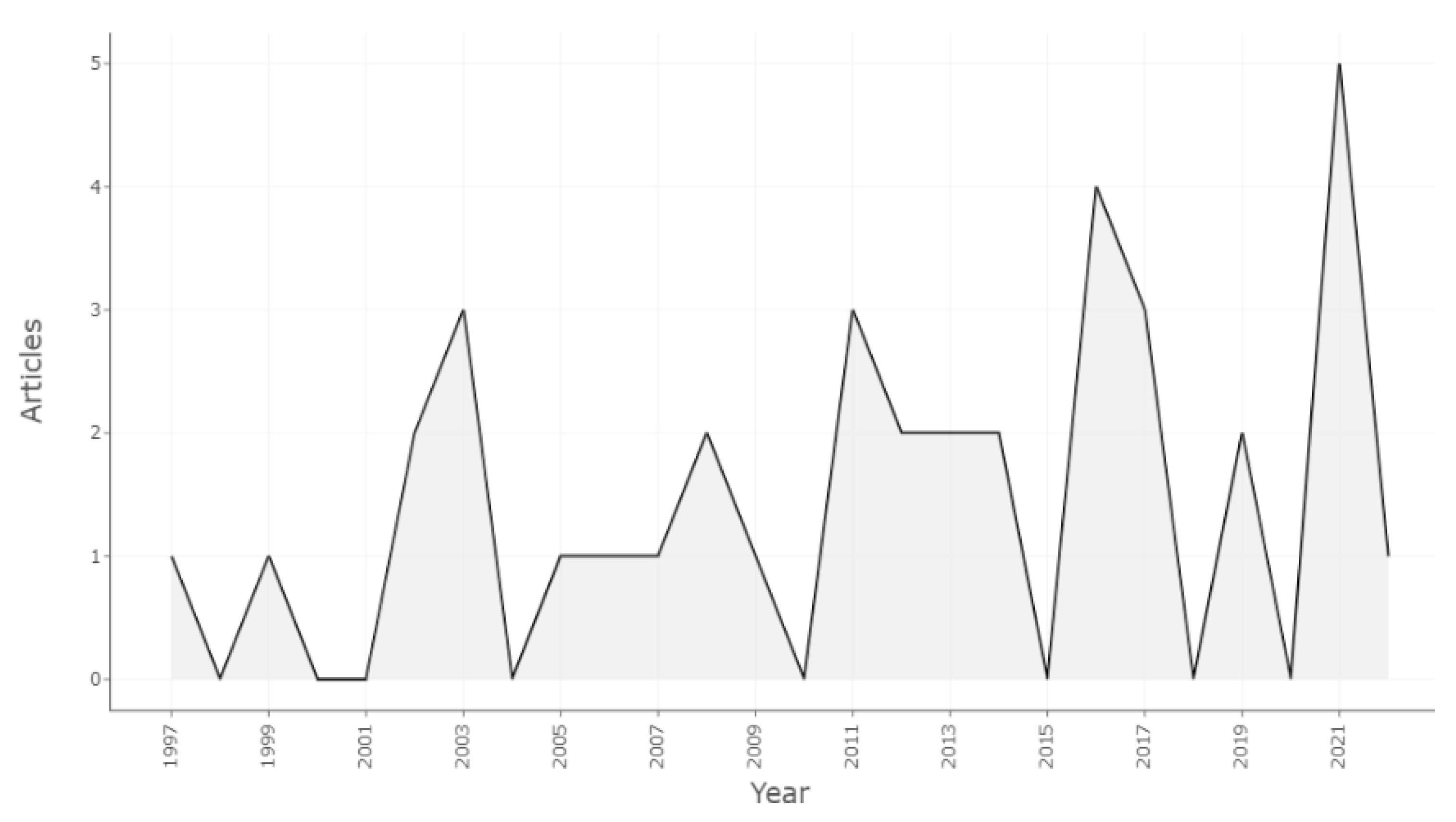

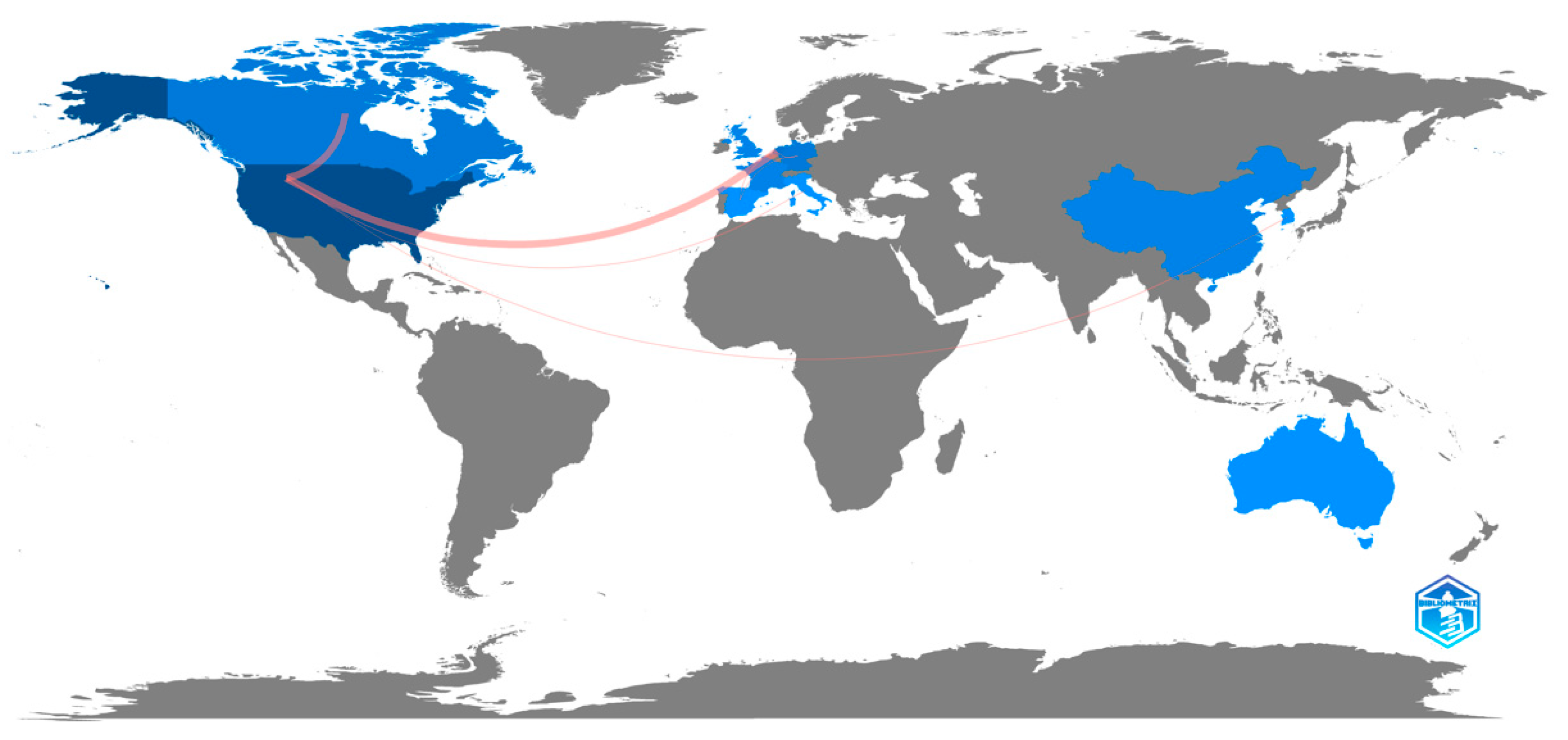

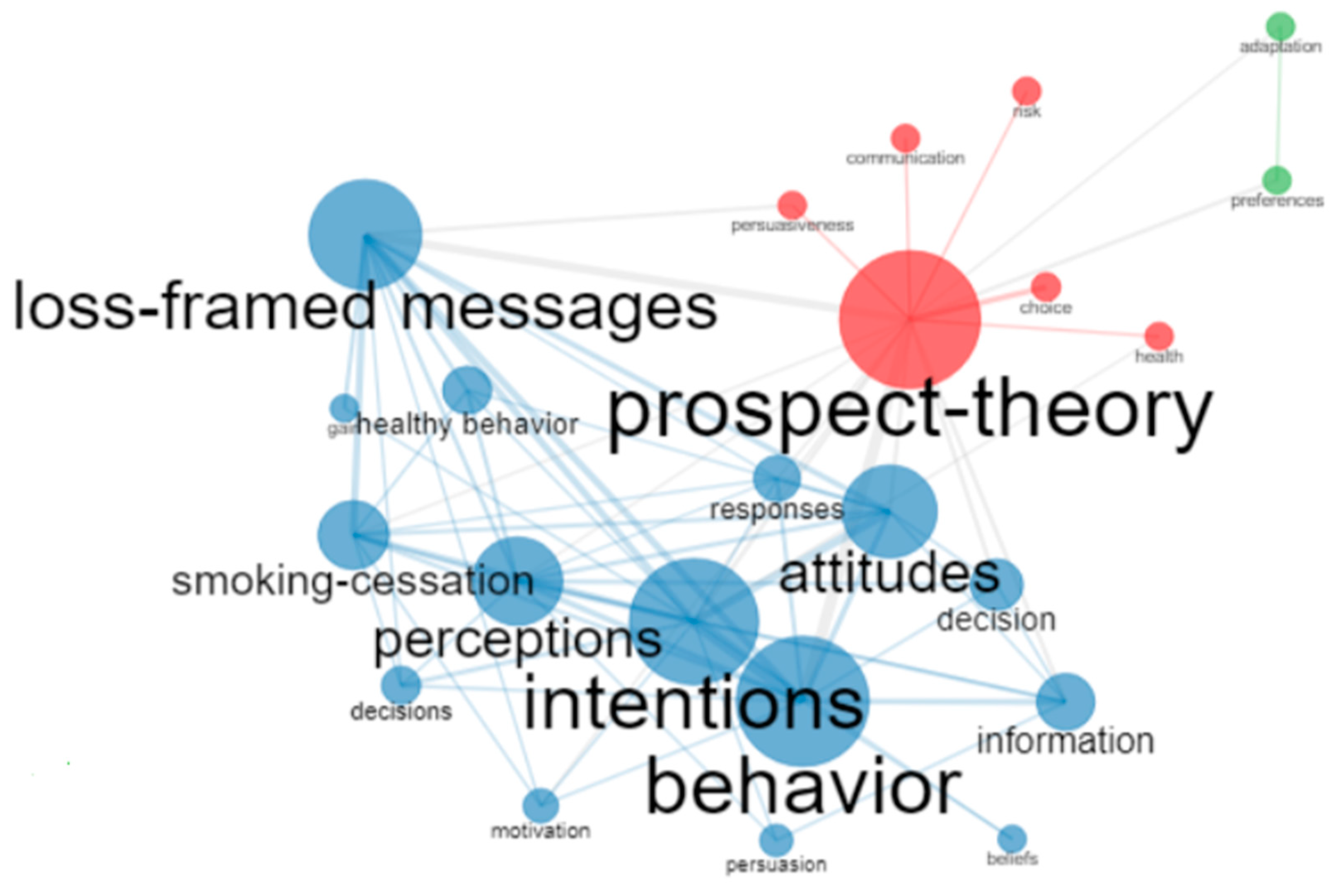

3.1. Results of Bibliometric Review

3.2. Results of Systematic Review

3.2.1. Prospective Theory and Health Care Field

3.2.2. Prospect Theory on Promoting Healthy Habits

3.2.3. PT, COVID Pandemic, and Social Behaviors

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Author | Main Aim | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Edwards [24] | Literature from behavioral economic, heuristic, and behavioral analysis in relation to explaining how cognitive biases in public health messaging, and how best to improve the effectiveness of PH messages | Review |

| 2021 | Kocas [32] | To apply PT and the anchoring heuristic to demonstrate how donors’ initial exposure to information during recruitment, as well as the way in which risk is framed throughout, may influence their perception and decision making | Theoretical |

| 2019 | DeStasio et al. [18] | To describe how health psychology and neuroeconomics can be mutually informative in the study of preventative health behaviors | Theoretical |

| 2016 | Van’t Riet et al. [39] | To examine the validity of the risk-framing hypothesis anew by providing a review of the health message-framing literature | Review |

| 2016 | Detweiler-Bedell & Detweiler-Bedell [25] | To explore the application of message framing, regulatory focus, construal level and psychological minds to goal setting and self-regulation, and they illustrate the powerful role of subjectivism in determining the effectiveness of health communication. | Theoretical |

| 2012 | Gallagher & Updegraff [44] | To distinguish the outcomes used to assess the persuasive impact of framed messages (attitudes, intentions, or behavior) | Review |

| 2011 | Mace & Le Lec [37] | To show that this fatalistic behavior can be explained through prospect theory by modeling this overly pessimistic view of old age as a failure to predict the change in the reference point due to hedonic adaptation | Theoretical |

| 2008 | Schwartz et al. [27] | To develop two approaches to reducing disutility by directing the decision maker’s attention to either (actual) past or (expected) future losses that result in shifted reference points, on the basis of PT | Theoretical |

| 2007 | Siu [45] | To examine effective message design in the promotion of exercise through PT and other theories | Theoretical |

| 1997 | Rothman & Salovey [19] | To consider how health recommendations are framed, focusing on the differences in how message framing is operationalized in formal decision problems and experiments in applied domains To examine the impact of message framing on health-relevant decision To explore if the persuasiveness of a framed recommendation relies on the extent to which the message is accepted or deflected by its recipient | Review |

| Year | Author | Aims | Sample | Methodology | Control Group | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Neumer et al. [58] | To use a health message intervention to motivate customers to engage in distancing behavior | N1 = 206 (M = 32.99, SD = 13.87, age range 14–78) N2 = 268 (M = 43.68, SD = 17.14, age range 15–86) | Online and field experiment 2 × 2 (gain-loss framed messages and targeting different beneficiaries) | No-intervention baseline | The intervention was more effective when targeting customers than citizens (Exp. 1–2) Loss-framed messages were more effective than gain-framed ones (Exp. 2) Perceptions of risk/worry statistically mediated the effect of messages targeting self-benefits on distancing intentions and behavior | (1) Loss-frame manipulation represents the worst-case consequence (2) Self-developed shortened items (3) Not assess demographics for the Exp. 2 |

| 2021 | Reinhardt & Rossman [43] | To investigate the effects of framing on younger and older adults’ reactance arousal, attitudes toward the coronavirus vaccination, vaccination intention, and recognition performance | N = 281 (M = 50.1, SD = 23.5) | Online experiment 2 × 2 (gain-loss frame and participants’ age) | Control variables | Loss framing positively influenced vaccination attitudes and led to stronger vaccination intentions among younger adults, but decreased recognition accuracy No framing effects In older adults | (1) Cross-sectional data (2) Higher predisposition to vaccination in older adults (vulnerability for infectious diseases) (3) Possible socially desirable responding (4) Text-only stimuli |

| 2021 | Doerfler et al. [56] | To investigate the effects of message framing and personality in relation to risky decision-making during the COVID-19 crisis | N = 294 (M = 39.01, SD = 13.75, age range: 18–78) | Asian Disease Problem (modified) and Dirty Dozen Scale (personality) | No | Both gain- and loss-framing influenced risk choice in response to COVID-19, with more risk-averse in the loss condition Psychopathy emerged as a significant predictor of risk-taking | (1) 40-year-old instrument (2) Brief measure of the Dark Triad traits (3) Sample limited to US-located participants |

| 2021 | Fridman [26] | To explore the association between words related to gains or losses and patients’ choices following physician–patient consultations | N = 208 | Analysis of transcribed consultations and pre-post treatment decisions | Control variable | Physicians who recommended immediate cancer treatment for cancer used fewer words related to losses and significantly fewer words related to death from cancer Physicians’ use of loss-related words correlated with recommendations for cancer treatment, and loss words were associated with patients’ choice of treatment | (1) Automated text analysis (2) Focus on “gains” and “losses”, just related to cancer survival or cancer death (3) Only male patients |

| 2019 | De Bruijn [54] | To explore the effects of message framing to promote dental hygiene | N = 549 (M = 47.4, SD = 16.1, age range 18–87) | 2-weeks online experimental study 2 × 2 (behavioral function (detection or prevention) and message frame (gain or loss)) | No Baseline | Participants were more likely to select a mouth rinse product that had a preventive function when that prevention function message emphasized gain-framed information Message frame did not impact choice in the detection function condition | (1) Self-reported post-intervention measurement (2) 20% of participants were excluded (3) Priming task to induce either a general non-behavior specific risk-seeking or averse mindset |

| 2017 | Lim & Noh [48] | To examine the effect of message framing on users’ intentions to adopt fitness applications | N = 100 (M = 22.3, age range 18–31) | Laboratory experiment employing a designed fitness app (gain- and loss-framed) | No | Advantage of gain-framed messages over loss-framed messages in increasing user’s intentions to use the app Gain-framed messages on users’ intentions to use the fitness app was mediated through exercise self-efficacy and outcome expectations of exercise | (1) No long-term tracking of the behavioral change (2) One period of data collection (3) Text-based message intervention (4) Exercise limited to simple sit-ups |

| 2017 | Vezich et al. [53] | To extend predict real-world behaviors (sunscreen use) from neural activity by making direct links to select theories relevant to persuasion | N = 37 women (M = 20.43, SD = 2.44) | Questionnaires, fMRI and 40 text-based ads promoting sunscreen use | No Control ads | Greater MPFC activity to gain- vs. loss-framed messages, and this activity was associated with behavior Stronger relationship for those who were not previously sunscreen users results reinforce that persuasion occurs in part via self-value integration | |

| 2016 | Malhotra et al. [33] | To compare attitudes of community- dwelling older adults and patients with advanced cancer for length and quality of life and assess whether these attitudes change with age | N = 1067 CDOAs N = 320 stage IV cancer patients | Quality-quantity (QQ) questionnaire | No Control for differences in sociodemographic characteristics | Lower proportion of CDOAs (26%) than patients (42%) were relatively more inclined towards length over quality of life. With increasing age, the difference in relative inclination between CDOAs and patients increased | (1) Not representative sample (2) Response rate could not be calculated (3) Possible differences in patients (4) Decisions possibly influenced by recommendations |

| 2016 | Burns & Rottman [50] | To examine how evaluations of healthiness change as participants consider eating increasing quantities of fruit and to explore how additional contextual features | N = 55 (M = 21.98) N = 72 (M = 20.6) | A 5 (quantity: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) × 2 (variety: same, variety) × 5 (fruit type: apple, pear, orange, banana, peach) within-subjects design | No | Health benefits that people assign to eating increasing quantities of fruit seem to increase, but only if eating a variety of fruits throughout the day is considered | (1) Lack of ecological validity (2) Individual differences may interact with the manipulations employed |

| 2016 | Lucas et al. [28] | To examine the effect of gain versus loss-framed messaging as well as culturally targeted personal prevention messaging on African Americans’ receptivity to colorectal cancer (CRC) screening | N = 132 African-American sample | Online education module about CRC, and exposition to a gain-framed or loss-framed message about CRC screening (2 × 2 × 2) | Yes | Cultural difference in the effect of message framing on illness screening White Americans were more receptive to CRC screening when exposed to a loss-framed message and African Americans were more receptive when exposed to a gain-framed message | (1) Statistically significant differences were not always observed for the reported health messaging differences (2) Small sample size and specific sociodemographic sample (3) CRC screening behavior was not presently assessed |

| 2014 | Van’t Riet et al. [40] | To examine the validity of the risk-framing hypothesis | N1 = 282 (M = 23.3, SD = 4.55, age range = 18–53) N2 = 542 (M = 31.8, SD = 9.96, age range = 18–75) N3 = 672 (M = 44.7, SD = 14.6, age range = 15–82) N4 = 679 (M = 44.4, SD = 13.9, age range = 18–79) N5 = 80 (M = 21.6, SD = 4.25, age range = 18–49) N6 = 125(M = 22.9, SD = 5.94, age range = 18–58) | Six empirical studies on the interaction between perceived risk and message Framing (two different countries and employed framed messages targeting skin cancer prevention and detection, physical activity, breast self-examination and vaccination behavior) | No | No evidence in support of the risk-framing hypothesis | (1) Behavioral intention as primary outcome (weak evidence that framing affects behavioral outcomes differently than attitudinal/intentional outcomes) (2) Some samples are women only |

| 2014 | Li et al. [47] | To compare message-framing effects on physical activity (PA) across age and gender groups | N = 111 younger adults (M = 2.31, SD = 3.04, age range = 18–35) N = 100 older adults (M = 71.66, SD = 7.48, age range = >60) | Questionnaires (IPAQ pre-post, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Subjective evaluation of the messages), accelerometer during 14 days, | No Manipulation check (demographics) | Significant age-by-gender by-framing interactions predicting self-report and accelerometer- assessed PA Older men may benefit particularly from gain-framed PA promotion messages | (1) Self-report items (2) Limited generalizability (3) Not representative groups in terms of the demographic and health-related variables (4) More physical than social benefits |

| 2013 | Mathur et al. [29] | To investigate the effectiveness of health message framing (gain/loss) depending on the nature of advocacy (prevention/detection) and respondents’ implicit theories (entity/incremental) | N1 = 68 N2 = 93 N3 = 251 | Exp 1. Two-part experiment randomly assigned to a gain or loss frame condition Exp 2. 2 × 2 (implicit theory × frame) between-subjects experiment Exp 3. 2 × 2 × 2 (implicit theory × frame × advocacy) between-subjects design | No | For detection advocacies, incremental theorists are more persuaded by loss-frames. For prevention advocacies, incremental theorists are more persuaded by gain-frames. For both advocacies (detection and prevention), entity theorists are not differentially influenced by frame Entity theorists are message advocacy sensitive, regardless of the message frame. | |

| 2013 | Churchill & Pavey [51] | To explore whether autonomy moderated the effectiveness of gain-framed vs. loss-framed messages encouraging fruit and vegetable consumption | N = 177 (M = 21.46, SD = 5.89, age range = 18–57) | Prospective design involving two waves of data collection Questionnaires (demographics, baseline fruit and vegetable consumption, autonomy, framed messages, BMI) | No | Autonomy moderated the effect of message framing. Gain-framed messages only prompted fruit and vegetable consumption amongst those with high levels of autonomy | (1) Self-report measure |

| 2012 | Foster et al. [38] | To test the empirical implications of competing theories about how expectations of outcomes affect utility | N = 13,479 (M = 46.05, SD = 16.70) | 6-year survey (demographics, SF-36 and health relevant behaviors scale) | No Baseline | Expecting good health in the future increases happiness now | (1) No direct effect of expected outcomes (2) Not clearly if it is sufficiently controlled for current health (3) Individuals relate their health to their prior expectations or to their actual health in the past |

| 2011 | Verlhiac et al. [55] | To examine if preventive-behavior framing and outcomes of action framing moderate behavioral intention to stop smoking when health messages are illustrated by pictures | N = 11 (M = 2.1, SD = 0.65) | 2 (Preventive Action: presence vs. absence) × 2 (Outcome Behavior: gain vs. loss) × 2 (Outcome Pictures: healthy mouths vs. unhealthy mouths) between-subjects factorial design and questionnaires (State anxiety, behavioral intention) | Yes | Behavioral intention was higher when pictures of unhealthy mouths were presented, regardless of framing, and when pictures of healthy mouths illustrated the presence of preventive action | (1) External validity issues |

| 2011 | Gallagher & Updegraff [44] | To examine the effect of fit between the frame and the type of outcome emphasized in a message on subsequent physical activity | N = 192 sedentary adults (M = 19.0, SD = 1.91, age range 16–35) | 2 × 2 (frame and extrinsic or intrinsic outcomes) and questionnaires (18-item Need for Cognition (NC) Scale, Exercise Attitudes, Follow-up Exercise, Past Exercise) | No | The predicted interaction between frame, outcome and NC was found such that a ‘fit’ message promoted somewhat, but not significantly, greater exercise for those with high NC, but a ‘non-fit’ message promoted significantly greater exercise for those with low NC | |

| 2009 | Winter et al. [34] | To examine through PT if sicker people evaluate quality of life in future health status more positively, compared to healthier people | N = 230 elderly people (M = 76.8, SD = 5.5, age range 69–95) | YDL questionnaire, ADL and IADL (current physical functioning) and demographics | Yes | Interaction between current health status and health scenario supported the relative acceptability of poor-health prospects to sicker individuals | (1) Relatively healthy sample (2) Cross-sectional study (3) Possible race effect |

| 2008 | Latimer et al. [46] | Messages to motivate the practice of physical activity emphasizing the benefits (gains) and the costs of inactivity (losses) | N = 332 sedentary people | Sending framed messages and a mixture of the two, and study of cognitive variables and self-reported physical activity in interviews on three occasions | Yes | Gain and mixed frame messages resulted in higher intentions and greater self-efficacy than the loss frame messages (week 2) Gain messages implied increased physical activity (week 9) | (1) Measurement limitations (2) Sample homogeneity (3) Participant-related factors |

| 2006 | Lacey et al. [35] | To look at how patients and non-patients rate descriptions of health conditions that differ in severity | N = 159 lung disease patients (M = 67.5, SD = 11.3, age range 23–90) N = 196 healthy participants (M = 39.9, SD = 13.1, age range 18–83) | Survey materials with lung conditions with different levels of severity and QoL questionnaire | Context and no context condition | Perspective of the raters (i.e., their own current health relative to the health conditions they rated) influences the way they distinguish between different health states that vary in severity | |

| 2005 | Lauriola et al. [42] | To examine how personality factors affected both risk-taking in decision-making tasks and in real-world health behaviors | N = 240 (M = 46.99, SD = 19.01, age range 20–80) | Framing experiments 3 × 2 (framing condition × valence) about blood cholesterol level or vitamin consumption level Questionnaires (EPQ-R, BIS-BAS, Barratt Scale, the Multidimensional Health Questionnaire, and Coronary Heart Disease items | No | More risk-taking in the negative risky choice framing valence condition and more negative health status evaluation in the negative attribute-framing valence condition. Impulsiveness, Anxiety, Health Involvement and Health Negative Affect correlated with message effectiveness in the goal-framing task and with the observed risk attitude in the risky choice task | |

| 2003 | Apanovitch et al. [30] | To compare the effectiveness of 4 videotaped educational programs designed to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women | N = 480 (M = 32, SD = 8.76, age range 18–50) | Structured interviews pre-post, framed videotaped program, self-reported information (HIV and risk factors) | No | Participants’ perceptions of the certainty of the outcome of an HIV test moderated the effects of framing on self-reported testing behavior 6 months after video exposure. In the certain outcome, those who saw a gain-framed video reported a higher rate of testing than those who saw a loss-framed message. | (1) Self-reported information (2) Increased perception of risk and uncertainty diminished the effects of message framing (3) No control condition |

| 2003 | Jones et al. [49] | To study the influence of the source credibility and message framing in the promotion of physical exercise in university students | N = 192 (M = 19.81, SD = 4.05) | Positively or negatively skewed messages and questionnaires to assess the impact on intentions and physical exercise | No | It Is helpful to provide exercise-related information highlighting the benefits to motivate clients to exercise | (1) Homogeneous sample (2) Non-objective techniques (3) Lack of impact of persuasive communication on attitudes towards exercise |

| 2003 | Winter et al. [36] | To test PT as a model of preferences for prolonging life under various hypothetical health states | N = 384 older people in shared housing (M = 80.6, SD = 7.0) | QoL (Quality of life) questionnaire | No | Participants with health problems preferred a longer life with poorer health conditions than did healthy participants. | (1) General problems due to the type of sample |

| 2002 | Broemer [41] | To test the hypothesis that the degree of experienced ambivalence toward health behaviors moderates the impact of differently framed messages | Exp. 1. N = 80 (M = 24.4,SD = 3.89) Exp. 2. N = 120 (M = 25.2, SD = 3.15) Exp. 3. N = 80 (M = 17.6, SD = 2.65) | Health attitudes survey with two framed conditions and questionnaires (perceived personal risk, perceived relevance of health issue, ambivalence, evaluation of the message, attitudes, cognitive elaboration) | No | Highly ambivalent individuals are more persuaded by negatively framed messages whereas individuals low in ambivalence are more persuaded by positively framed messages | (1) Only male participants (exp.1) (2) Not provide direct evidence that ambivalence determines how much subjective weight is given to different health-related outcomes (3) Role of salient behavioral norms might affect reactions to persuasive appeals |

| 2002 | Finney & Iannotti [31] | To evaluate an intervention derived from prospect theory that was designed to increase women’s adherence to recommendation for annual mammography screening | N = 929 (age range 40–69) | 1 of 3 reminder letters (positive frame, negative frame, or standard hospital prompt | No | The hypothesis that women with a positive history would be more responsive to negatively framed messages, whereas women with a negative history would be more responsive to positively framed letters was not confirmed | (1) Small sample size (2) Is it possible that someone hadn’t receive the message (3) Previous experience with mammography messages |

| 1999 | Detweiler-Bedell et al. [52] | Use PT to predict that messages highlighting potential “gains” should promote prevention behaviors such as sunscreen use best | N = 217 (M = 38.7, age range 18–79) | Experiment to compare the effectiveness of 4 differently framed messages (2 highlighting gains, 2 highlighting losses) to obtain and use sunscreen Questionnaires (attitudes and intentions) | No | People who read either of the 2 gain-framed brochures, compared with those who read either of the 2 loss-framed brochures, were significantly more likely to (a) request sunscreen, (b) intend to repeatedly apply sunscreen while at the beach, and (c) intend to use sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 15 or higher | (1) Brief intervention (2) Restricted nature of primary behavioral measure: requests for sunscreen with an SPF of 15 (3) Not collect long-term data |

References

- Edwards, W. The theory of decision making. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 5, 380–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometría 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Rational choice and the framing of decisions. In Rational Choice: The Contrast between Economics and Psychology; Hogarth, R.M., Reder, M.W., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987; pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Molins, F.; Serrano, M.A. Bases neurales de la aversión a las pérdidas en contextos económicos: Revisión sistemática según las directrices PRISMA. Rev. De Neurol. 2019, 68, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.; Bromiley, P.; Devers, C.; Holcomb, T.; McGuire, J. Management Theory Applications of Prospect Theory: Accomplishments, Challenges, and Opportunities. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1069–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. To win and lose—Linguistic aspects of Prospect-Theory. Lang. Cogn. Process. 1992, 7, 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.L.; Bruce, A. Prospect theory and body mass: Characterizing psychological parameters for weight-related risk attitudes and weight-gain aversion. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N.C. Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2012, 27, 18621. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. A Prospect Theory Approach to Understanding Conservatism. Philosophia 2017, 45, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieider, F.M.; Vis, B. Prospect Theory and Political Decision Making. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Politics 2019, 3, 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Vis, B. Prospect Theory and Political Decision Making. Political Stud. Rev. 2011, 9, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heutel, G. Prospect Theory and Energy Efficiency. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 96, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, C. A Prospect Theory Perspective on Terrorism. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, O.; Jong-A-Pin, R.; Schoonbeek, L. A prospect-theory model of voter turnout. CESifo Work. Pap. 2019, 168, 362–373. [Google Scholar]

- Osberghaus, D. Prospect theory, mitigation and adaptation to climate change. J. Risk Res. 2017, 20, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Daily, K.; Qin, Y. Relative persuasiveness of gain-vs. loss-framed messages: A review of theoretical perspectives and developing an integrative framework. Rev. Commun. 2018, 18, 370–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeStasio, K.L.; Clithero, J.A.; Berkman, E.T. Neuroeconomics, health psychology, and the interdisciplinary study of preventative health behavior. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2019, 13, e12500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.J.; Salovey, P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, M. Prospect Theory in Times of a Pandemic: The Effects of Gain versus Loss Framing on Risky Choices and Emotional Responses during the 2020 Coronavirus Outbreak—Evidence from the US and the Netherlands. Mass Communitacion Soc. 2021, 24, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo-Peris, J.; González-Sala, F.; Merino-Soto, C.; Pablo, J.Á.C.; Toledano-Toledano, F. Decision Making in Addictive Behaviors Based on Prospect Theory: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J. Ensuring Effective Public Health Communication: Insights and Modeling Efforts From Theories of Behavioral Economics, Heuristics, and Behavioral Analysis for Decision Making Under Risk. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 715159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detweiler-Bedell, B.; Detweiler-Bedell, J.B. Emerging trends in health communication: The powerful role of subjectivism in moderating the effectiveness of persuasive health appeals. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, I.; Fagerlin, A.; Scherr, K.A.; Scherer, L.D.; Huffstetler, H.; Ubel, P.A. Gain–loss framing and patients’ decisions: A linguistic examination of information framing in physician–patient conversations. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.; Goldberg, J.; Hazen, G. Prospect theory, reference points, and health decisions. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2008, 3, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, T.; Hayman, L.W., Jr.; Blessman, J.E.; Asabigi, K.; Novak, J.M. Gain versus loss-framed messaging and colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: A preliminary examination of perceived racism and culturally targeted dual messaging. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, P.; Jain, S.P.; Hsieh, M.-H.; Lindsey, C.D.; Maheswaran, D. The influence of implicit theories and message frame on the persuasiveness of disease prevention and detection advocacies. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 122, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanovitch, A.M.; McCarthy, D.; Salovey, P. Using message framing to motivate HIV testing among low-income, ethnic minority women. Health psychology: Official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2003, 22, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, L.J.; Iannotti, R.J. Message framing and mammography screening: A theory-driven intervention. Behav. Med. 2002, 28, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocas, H.D.; Pavlenko, T.; Yom, E.; Rubin, L.R. The long-term medical risks of egg donation: Contributions through psychology. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2021, 7, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, C.; Xiang, L.; Ozdemir, S.; Kanesvaran, R.; Chan, N.; Finkelstein, E.A. A comparison of attitudes toward length and quality of life between community-dwelling older adults and patients with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2017, 26, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, L.; Moss, M.S.; Hoffman, C. Affective forecasting and advance care planning: Anticipating quality of life in future health statuses. J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, H.P.; Fagerlin, A.; Loewenstein, G.; Smith, D.M.; Riis, J.; Ubel, P.A. It must be awful for them: Perspectives and task context affects ratings for health conditions. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2006, 1, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, L.; Lawton, M.P.; Ruckdeschel, K. Preferences for Prolonging Life: A Prospect Theory Approach. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2003, 56, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macé, S.; Le Lec, F. On fatalistic long-term health behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011, 32, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Frijters, P.; Johnston, D.W. The triumph of hope over disappointment: A note on the utility value of good health expectations. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van ‘t Riet, J.; Cox, A.D.; Cox, D.; Zimet, G.D. Does Perceived Risk Influence the Effects of Message Framing? Revisiting the Link between Prospect Theory and Message Framing. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van ‘t Riet, J.; Cox, A.D.; Cox, D.; Zimet, G.D.; De Bruijn, G.J.; Van den Putte, B.; De Vries, H.; Werrij, M.Q.; Ruiter, R.A. Does perceived risk influence the effects of message framing? A new investigation of a widely held notion. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broemer, P. Relative effectiveness of differently framed health messages: The influence of ambivalence. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriola, M.; Russo, P.M.; Ludici, F.; Violani, C.; Levin, I.P. The role of personality in positively and negatively framed risky health decisions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, A.; Rossmann, C. Age-related framing effects: Why vaccination against COVID-19 should be promoted differently in younger and older adults. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2021, 27, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. When ‘fit’ leads to fit, and when ‘fit’ leads to fat: How message framing and intrinsic vs. extrinsic exercise outcomes interact in promoting physical activity. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, W.L. Prime, frame, and source factors: Semantic valence in message judgment. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 2364–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, A.E.; Rench, T.A.; Rivers, S.E.; Katulak, N.A.; Materese, S.A.; Cadmus, L.; Hicks, A.; Keany Hodorowski, J.; Salovey, P. Promoting participation in physical activity using framed messages: An application of prospect theory. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.K.; Cheng, S.T.; Fung, H.H. Effects of message framing on self-report and accelerometer-assessed physical activity across age and gender groups. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Noh, G.-Y. Effects of gain-versus loss-framed performance feedback on the use of fitness apps: Mediating role of exercise self-efficacy and outcome expectations of exercise. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 77, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.W.; Sinclair, R.C.; Courneya, K.S. The effects of source credibility and message framing on exercise intentions, behaviors, and attitudes: An integration of the elaboration likelihood model and prospect theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 33, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.J.; Rothman, A.J. Evaluations of the health benefits of eating more fruit depend on the amount of fruit previously eaten, variety, and timing. Appetite 2006, 105, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.; Pavey, L. Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption: The role of message framing and autonomy. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detweiler, J.B.; Bedell, B.T.; Salovey, P.; Pronin, E.; Rothman, A.J. Message framing and sunscreen use: Gain-framed messages motivate beach-goers. Health psychology. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. 1999, 18, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezich, I.S.; Katzman, P.L.; Ames, D.L.; Falk, E.B.; Lieberman, M.D. Modulating the neural bases of persuasion: Why/how, gain/loss, and users/non-users. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017, 12, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruijn, G. To frame or not to frame? Effects of message framing and risk priming on mouth rinse use and intention in an adult population-based sample. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 42, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlhiac, J.-F.; Chappé, J.; Meyer, T. Do Threatening Messages Change Intentions to Give Up Tobacco Smoking? The Role of Argument Framing and Pictures of a Healthy Mouth Versus an Unhealthy Mouth. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 2104–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerfler, S.M.; Tajmirriyahi, M.; Dhaliwal, A.; Bradetich, A.J.; Ickes, W.; Levine, D.S. The Dark Triad trait of psychopathy and message framing predict risky decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumer, A.; Schweizer, T.; Bogdanić, V.; Boecker, L.; Loschelder, D.D. How health message framing and targets affect distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, R. Prospect theory in political science: Gains and losses from the first decade. Political Psychol. 2004, 25, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gisbert-Pérez, J.; Martí-Vilar, M.; González-Sala, F. Prospect Theory: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review in the Categories of Psychology in Web of Science. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102098

Gisbert-Pérez J, Martí-Vilar M, González-Sala F. Prospect Theory: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review in the Categories of Psychology in Web of Science. Healthcare. 2022; 10(10):2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102098

Chicago/Turabian StyleGisbert-Pérez, Júlia, Manuel Martí-Vilar, and Francisco González-Sala. 2022. "Prospect Theory: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review in the Categories of Psychology in Web of Science" Healthcare 10, no. 10: 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102098

APA StyleGisbert-Pérez, J., Martí-Vilar, M., & González-Sala, F. (2022). Prospect Theory: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review in the Categories of Psychology in Web of Science. Healthcare, 10(10), 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10102098