A Phenominological Qualitative Study of Factors Influencing the Migration of South African Anaesthetists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting and Population

2.3. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Sampling Process and Participant’s Recruitment Strategy

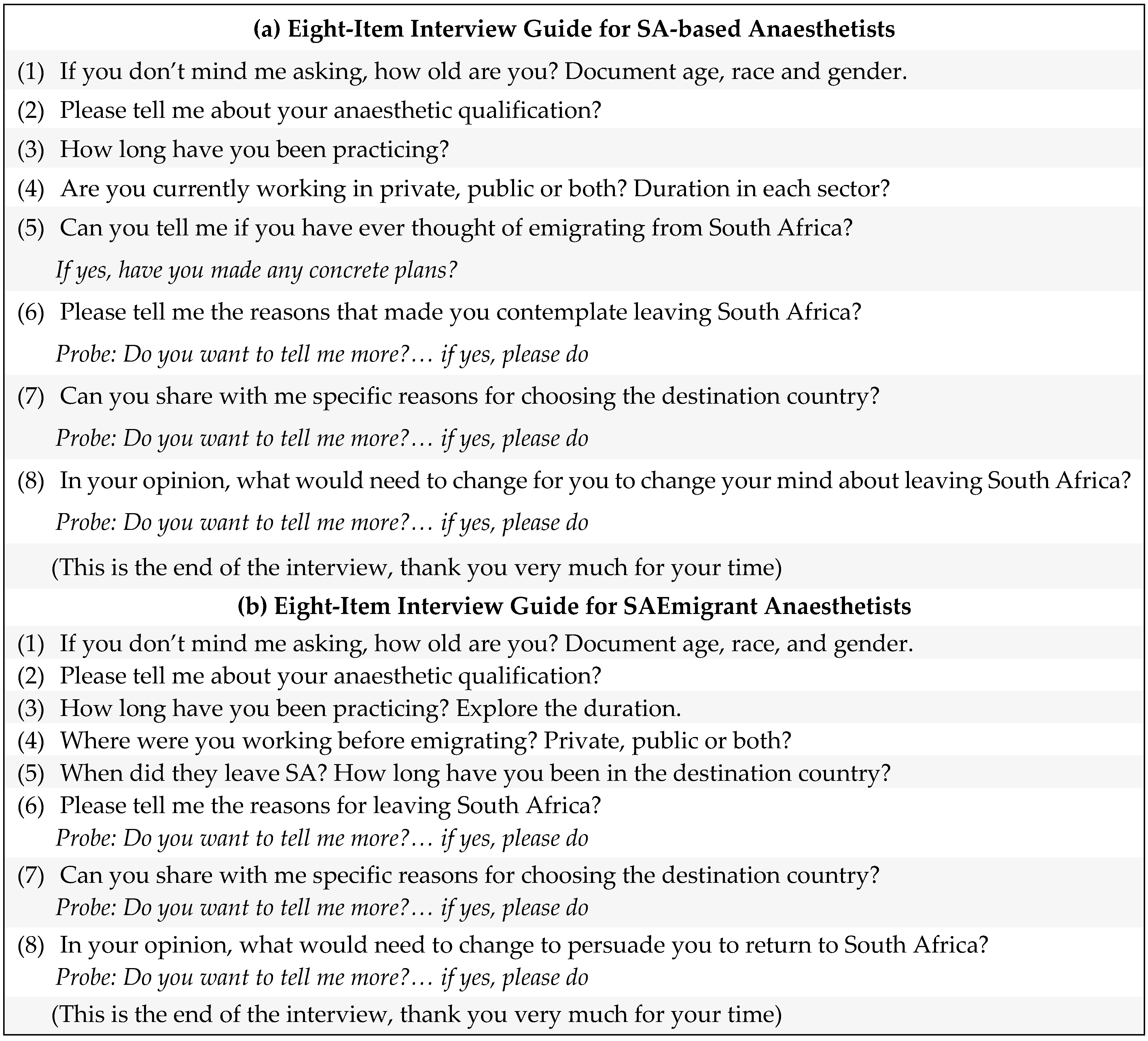

2.5. Data Collection Process

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographics of the Study Participants

4.2. Emerging Themes and Sub-Themes

4.3. Emigration Plan

“I haven’t made the decision to leave. I have made the decision to make plans.” P16

4.4. Factors Influencing Emigration Plan

“The crime in the country, the economic situation in the country, and the political instability. It’s mostly those three factors that started plaguing me.” P1

“The main reason was just to explore what it’s like working in the first world countries… No absolutely, I didn’t move because of South Africa. I just wanted to develop myself and try and progress academically just to broaden my experience.” P4

4.4.1. Push Factors: Donor Country Factors Encouraging Emigration

“Looking around at the moment in anaesthesia in Cape town, so many people are leaving. So many anaesthetists are leaving but I just feel like ‘am I being stupid by not leaving’ and in a couple of years I would kick myself and say, ‘why didn’t I leave at the time when we could’. And it’s scary like everyone is just leaving and I’m scared to be left behind, and I’m scared but I don’t want to go; it’s not a nice place to be in.” P19

“If NHI would to take over and we won’t be able to access medical care like we do now. I don’t know, it would be probably one of my main reasons for wanting to emigrate.” P9

“So physical safety; feeling safe in my house, feeling safe if I drive in the car, feeling safe to have children.” P20

“It was constantly a battle of ‘I know what the patient deserves but I’m physically unable to provide the care that the patients deserve’ because for example we don’t have syringes or we don’t have the needles or surgeries were cancelled because they didn’t order the right set. Or the autoclave is broken or ‘no we can’t do the elective procedures because the temperature in theatre is at twenty eight (28) degrees.” P8

“…and when you progress as a black woman, it is because you are black. I remember feeling very strongly against that at the time because I thought I was achieving a lot of things regardless of whether I was a black woman or not. But I thought it was always being overshadowed by my race, that people thought it must be easier for certain groups of people because we are the demographics that is supposed to be progressing, helped and chosen.” P4

“…private was becoming not an easy place to infiltrate, as I was hearing from senior colleagues. As a result, people who ordinarily would have moved on from the public sector and opened up consultant posts were just sitting in those posts, and there weren’t that many posts.” P21

4.4.2. Pull Factors: Destination Country Factors That Encourage Immigration

“What I like about the UK is there is a lot more...you feel quite protected by the system. So for example, if you get sick and you are meant to work night shift, you are not going to be expected to find someone to do the night shift as is often the case in South Africa. You are just sick and they will cover you, they will pay someone to cover your shift. I think in South Africa it’s a lot of responsibility towards being there. Even if you are not well.” P6

“So if I become a Fellow of College of Anaesthetists of Ireland, that is recognized in a lot of countries so it actually opens more doors in terms of if we were to move again, we could easily go somewhere else you know now I would again be able to practice without having to re-qualify all over again.” P8

“I think the biggest one for me is race, I need to be in a place where my family will be comfortable. I think New Zealand is an option due to that reason, it was more for the race factor. So it depends on how accepting or welcoming the country is to different races.” P1

4.4.3. Potential Factors That Would Influence Decision Not to Emigrate

“…So, the only type of sub-specialty we can do here is ICU. It is also quite hard to get in sometimes. So, I think if we offer more subspecialties especially for young or junior consultants it would be great. Or additional sort of research courses or whatever it is where you can actually sort of grow in a different way.” P12

“Things like family, things like being South African, being proud South African; growing up in South Africa and wanting to change and being part of a change for a better South Africa I think that’s reasons why one would stay.” P22

“I would think it would be a bigger balance or cooperation between private and public. I really love working in the public sector because it gives me access to a world of knowledge. I feel supported. You know in the sense of having colleagues and those kinds of things but it is very consuming and there is not much money or the money isn’t as much as you could get in private. Sometimes you do feel taken advantage of with regard to overtime so if that had to change, I would have a better work life balance or control over my life, my time…I would like to be in a space where I could work fifty private, fifty in government. And I think something like that would actually allow one to be more giving in the public sector, you would be more enthusiastic.” P18

5. Discussion

5.1. Emigration Plan

5.2. Factors Influencing Emigration Plan

5.3. Potential Factors That Would Influence the Decision Not to Emigrate

6. Strengths and Limitations

6.1. Strength

6.2. Limitations

- The concentration of the study population around a specific age group. The most likely explanation for this is the use of the snowball method to sample participants, since it relies on recommendations from other participants. This would indicate that this group of participants was often more enthusiastic about volunteering.

- An inherent limitation of qualitative research is the possible participant response bias which is created by researcher presence during the data collection process. The researcher’s own history of emigration could have created this bias.

- The findings from this qualitative study cannot be generalized to the whole anaesthetic workforce in SA due to the small sample size and therefore cannot be taken to represent all the views on emigration.

- The researcher could have interviewed key stakeholders within the South African Anaesthesia Fraternity such as SASA, CMSA and HPCSA to obtain their perspective.

7. Conclusions

8. Recommendations

8.1. Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA)

8.2. South African Society of Anaesthetists (SASA)

8.3. Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA) and Medical Universities Training Anaesthesiologists

8.4. Future Research Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mellin-Olsen, J. Migration and workforce planning in medicine with special focus on anesthesiology. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aluttis, C.; Bishaw, T.; Frank, M.W. The workforce for health in a globalized context–global shortages and international migration. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 23611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidwell, P.; Laxmikanth, P.; Blacklock, C.; Hayward, G.; Willcox, M.; Peersman, W.; Moosa, S.; Mant, D. Security and skills: The two key issues in health worker migration. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 24194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, G.; Reardon, C. Preparing for export? Medical and nursing student migration intentions post-qualification in South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2013, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awases, M.; Gbary, A.; Nyoni, J.; Chatora, R. Migration of Health Professionals in Six Countries: A Synthesis Report; World Health Organization; Regional Office for Africa: Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, 2004.

- Kempthorne, P.; Morriss, W.W.; Mellin-Olsen, J.; Gore-Booth, J. The WFSA global anesthesia workforce survey. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 125, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezuidenhout, M.M.; Joubert, G.; Hiemstra, L.A.; Struwig, M.C. Reasons for doctor migration from South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Practice. 2014, 51, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Udo, K.; Stefan, R. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA Text, Audio, and Video; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonté, R.; Sanders, D.; Mathole, T.; Crush, J.; Chikanda, A.; Dambisya, Y.; Runnels, V.; Packer, C.; MacKenzie, A.; Murphy, G.T.; et al. Health worker migration from South Africa: Causes, consequences and policy responses. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nwadiuko, J.; Switzer, G.E.; Stern, J.; Day, C.; Paina, L. South African physician emigration and return migration, 1991–2017: A trend analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Spuy, Z.M.; Zabow, T.; Good, A. Money isn’t everything–CMSA doctor survey shows some noteworthy results. S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 550–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, S. The South African national health insurance: A revolution in health-care delivery! J. Public Health 2012, 34, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofolo, N.; Heunis, C.; Kigozi, G.N. Corrigendum: Towards national health insurance: Alignment of strategic human resources in South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2021, 13, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benatar, S.; Gill, S. Universal access to healthcare: The case of South Africa in the comparative global context of the late Anthropocene era. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christmals, C.D.; Aidam, K. Implementation of the National health insurance scheme (NHIS) in Ghana: Lessons for South Africa and low-and middle-income countries. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, F.; Botha, C.J.; Bisschoff, C.A. Push and pull factors in relation to skills shortages in South Africa. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 30, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373. [Google Scholar]

| Sociodemographic Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 20–30 | 2 | 8.7 |

| 31–40 | 16 | 69 |

| 41–50 | 4 | 17.4 |

| 51–60 | 1 | 4.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 17 | 74 |

| Male | 6 | 26 |

| Race | ||

| White | 14 | 61 |

| Black | 6 | 26 |

| Indian | 2 | 8.7 |

| Coloured | 1 | 4.3 |

| Highest Anaesthetic Qualification | ||

| DA | 5 | 21.7 |

| FCA and/or MMed | 17 | 74 |

| PhD | 1 | 4.3 |

| Years of Experience | ||

| 1–5 | 2 | 8.7 |

| 6–10 | 13 | 56.6 |

| 11–15 | 5 | 21.7 |

| >16 | 3 | 13 |

| Emerging Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Emigration Plan |

|

| Factors Influencing Emigration Plan | Push factors

|

| Potential Factors That Would Influence Decision Not To Emigrate |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fletcher-Nkile, L.; Mrara, B.; Oladimeji, O. A Phenominological Qualitative Study of Factors Influencing the Migration of South African Anaesthetists. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112165

Fletcher-Nkile L, Mrara B, Oladimeji O. A Phenominological Qualitative Study of Factors Influencing the Migration of South African Anaesthetists. Healthcare. 2022; 10(11):2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112165

Chicago/Turabian StyleFletcher-Nkile, Leilanie, Busisiwe Mrara, and Olanrewaju Oladimeji. 2022. "A Phenominological Qualitative Study of Factors Influencing the Migration of South African Anaesthetists" Healthcare 10, no. 11: 2165. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112165