Framing of COVID-19 in Newspapers: A Perspective from the US-Mexico Border

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Analysis Procedure

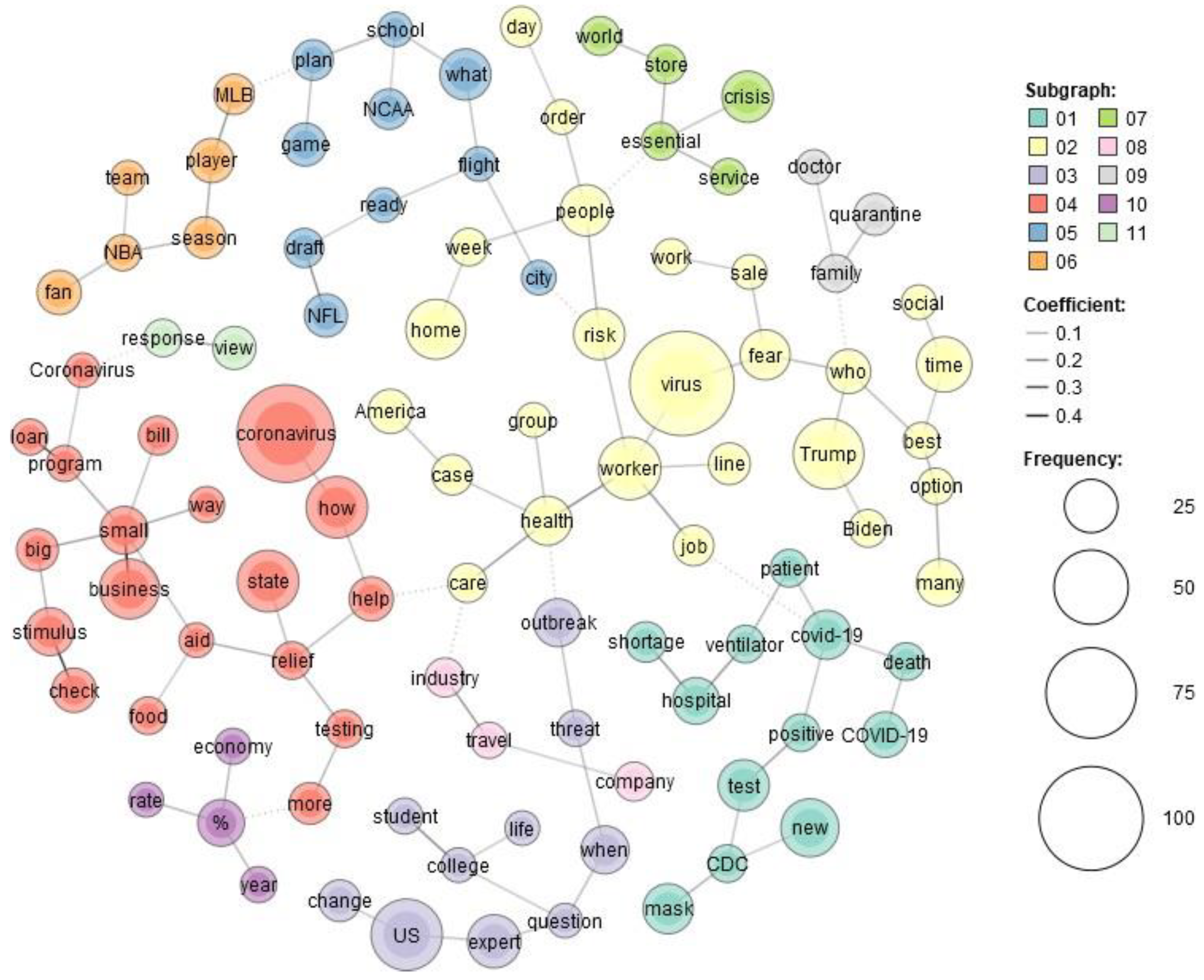

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, K.F.; Goldberg, M.; Rosenthal, S.; Carlson, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Ramachandran, S. Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jerit, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, M.; Wheeler, M. Differences between national and local media in news coverage of the Zika virus. Health Commun. 2018, 34, 1816–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratzan, S.C.; Moritsugu, K.P. Ebola crisis—Communication chaos we can avoid. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 1213–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konow-Lund, M.; Hågvar, Y.B.; Olsson, E. Digital innovation during terror and crises. Digit. J. 2019, 7, 952–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadouka, M.E.; Evangelopoulos, N.; Ignatow, G. Agenda setting and active audiences in online coverage of human trafficking. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionni, D.M. International human trafficking: An agenda-building analysis of the US and British press. Inter-Natl. Commun. Gazette 2012, 74, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, B.L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.E.; McCombs, M.E. Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public’s images and opinions about major corporations. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.E.; Llamas, J.P.; Lopez-Escobar, E. Candidate images in Spanish elections: Second-level agenda-setting effects. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 1997, 74, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, B.; Bode, L.; Shah, D.; Wilcox, D.; Shah, C. Agenda Setting in a Digital Age: Tracking Attention to California Proposition 8 in social media, Online News and Conventional News. Policy Internet 2010, 2, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeling, C.; Brookes, V.; Hill, T.; Hall, J.; Rowles, A.; Tull, C.; Mullan, J.; Byrne, M.; Reynolds, N.; Hawkins, O. Changes in the Framing of Antimicrobial Resistance in Print Media in Australia and the United Kingdom (2011–2020): A Comparative Qualitative Content and Trends Analysis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.S.; Chinn, S.; Soroka, S. Politicization and polarization in COVID-19 news coverage. Sci. Commun. 2020, 42, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihekweazu, C. Ebola in prime time: A content analysis of sensationalism and efficacy information in US nightly news coverage of the Ebola outbreaks. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, E.; Johnston, B.; Corlett, J.; Kearney, N. Constructing identities in the media: Newspaper coverage analysis of a major UK Clostridium difficile outbreak. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bawab, A.Q.; AlQahtani, F.; McElnay, J. Health care apps reported in newspapers: Content analysis. JMIR Mhealth uHealth 2018, 6, e10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.J.A. The Invention of Journalism Ethics: The Path to Objectivity and Beyond; McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, D. COVID-19 Has Ravaged American Newsrooms. Here’s Why That Matters. NiemanLab. 2020. Available online: http://www.niemanlab.org/2020/07/covid-19-has-ravaged-american-newsrooms-heres-why-that-matters/ (accessed on 4 July 2021).

- Hendrickson, C. Critical in a Public Health Crisis, COVID-19 Has Hit Local Newsrooms Hard. Brookings Institute. 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/08/critical-in-a-public-health-crisis-covid-19-has-hit-local-newsrooms-hard/ (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Oliver, J.E.; Lee, T. Public Opinion and the Politics of Obesity in America. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2005, 30, 923–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, E.F.; Gollust, S.E. The Content and Effect of Politicized Health Controversies. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2015, 658, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwakpoke Ogbodo, J.; Chike Onwe, E.; Chukwu, J.; Nwasum, C.J.; Nwakpu, E.S.; Ugochukwu Nwankwo, S.; Nwamini, S.; Elem, S.; Iroabuchi Ogbaeja, N. Communicating health crisis: A content analysis of global media framing of COVID-19. Health Promot. Perspect. 2020, 10, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, D. Gannett Closes Edinburg Review and Valley Town Crier. Rio Grande Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://riograndeguardian.com/gannett-closes-edinburg-review-and-valley-town-crier/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Bolstad, E. COVID-19 Is Crushing Newspapers, Worsening Hunger for Accurate Information. Pew.org. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/09/08/covid-19-is-crushing-newspapers-worsening-hunger-for-accurate-information (accessed on 3 July 2021).

- Ford, J.D.; King, D. Coverage and framing of climate change adaptation in the media: A review of influential North American newspapers during 1993–2013. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 48, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damstra, A.; Vliegenthart, R. (Un)covering the Economic Crisis? J. Stud. 2018, 19, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, E. Americans Turning More to Local News Since the COVID-19 Crisis. World Economic Forum. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/local-news-is-playing-an-important-role-for-americans-during-covid-19-outbreak (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Mitchell, A.; Oliphant, J.B.; Shearer, E. COVID-19: Both a National and Local News Story. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. 2020. Available online: https://www.journalism.org/2020/04/29/2-covid-19-both-a-national-and-local-news-story/ (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Glaser, M. 3 Ways Local News Initiatives are Serving Crucial COVID-19 Information to People in News Deserts. Knight Foundation. 2020. Available online: https://knightfoundation.org/articles/3-ways-local-news-initiatives-are-serving-crucial-covid-19-information-to-people-in-news-deserts/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Ntoumi, F.; Zumla, A. Advancing accurate metrics for future pandemic preparedness. Lancet 2022, 399, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S.; Willenson, E. Research Opportunities in Preparing Supply Chains of Essential Goods for Future Pandemics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass Media and Society. Local versus National News. 2016. Available online: https://sites.psu.edu/rmg5539/2016/07/17/local-versus-national-news/#:~:text=Local%20newspapers%20are%20heavily%20relied (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Heyvaert, M.; Hannes, K.; Maes, B.; Onghena, P. Critical Appraisal of Mixed Methods Studies. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2013, 7, 302–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, J.; Bernal, P.; Román, E.; González, M.; Giménez, G.; Aragón, Ó.; Roé, L.; López, E.; Rodríguez, J.; Morales, C. Sentiment analysis as a qualitative methodology to analyze social media: Study case of tourism. CIAIQ2016 2016, 5, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, H.; Heale, R. Triangulation in research, with Examples. Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regnault, A.; Willgoss, T.; Barbic, S. Towards the use of mixed methods inquiry as best practice in health outcomes research. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2018, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greene, J.C.; Caracelli, V.J.; Graham, W.F. Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1989, 11, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilich, S.; Kreimer, A.; Meilijson, I.; Gophna, U.; Sharan, R.; Ruppin, E. The large-scale organization of the bacterial network of ecological co-occurrence interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 3857–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, M.A.; Parnell, J.; Arici, H. Co-occurrence network analysis (CNA) as an alternative tool to assess survey-based research models in hospitality and tourism research. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2022, 7, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Understanding Fatal Crash Reporting Patterns in Bangladeshi Online Media using Text Mining. J. Transp. Res. Board 2021, 2675, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumans, J.W.; Trilling, D. Taking Stock of the Toolkit. Digit. J. 2015, 4, 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart, R.; van Zoonen, L. Power to the frame: Bringing sociology back to frame analysis. Eur. J. Commun. 2011, 26, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hansen, C.; Vu, H.T. Meditation as panacea: A longitudinal semantic network analysis of meditation coverage in campus newspapers from 1997–2018. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Mir, G.C.; Iannone, B.V.; Pijanowski, B.C.; Kong, N.; Fei, S. Automated content analysis: Addressing the big literature challenge in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ong’ong’a, D.O.; Mutua, S.N. Online News Media Framing of COVID-19 Pandemic: Probing the Initial Phases of the Disease Outbreak in International Media. Eur. J. Interact. Multimed. Educ. 2020, 1, e02006. [Google Scholar]

- Victory, M.; Do, T.Q.N.; Kuo, Y.; Rodriguez, A.M. Parental knowledge gaps and barriers for children receiving human papillomavirus vaccine in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. The Unique Challenges of Surveying U.S. Latinos. 2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2015/11/12/the-unique-challenges-of-surveying-u-s-latinos/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Tabler, J.; Mykyta, L.; Schmitz, R.M.; Kamimura, A.; Martinez, D.A.; Martinez, R.D.; Flores, P.; Gonzalez, K.; Marquez, A.; Marroquin, G. Getting by with a little help from our friends: The role of social support in addressing HIV-related mental health disparities among sexual minorities in the lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C.C.; Sierra, L.A. Anti-immigrant rhetoric, deteriorating health access, and COVID-19 in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas. Health Secur. 2021, 19 (Suppl. 1), S-50–S-56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, C.H.; Kecojevic, A.; Wagner, V.H. Coverage of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Online Versions of Highly Circulated U. S. Daily Newspapers. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Echo Media. 2020. Available online: https://echo-media.com/medias/geo_listing/N/TX/636/harlingen-weslaco-brownsville-mcallen (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Christoffersen, K. Linguistic Terrorism in the Borderlands: Language Ideologies in the Narratives of Young Adults in the Rio Grande Valley. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2019, 13, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, D.Z. The Community Union model of organizing in Rio Grande Valley colonias. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2020, 239965442091139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.M.; Correa, J.G. Abrogation of Public Trust in the Protected Lands of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, E.; Vogler, J. Ditch Urbanism. J. Archit. Educ. 2020, 74, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilfinger Messias, D.K.; Sharpe, P.A.; del Castillo-González, L.; Treviño, L.; Parra-Medina, D. Living in Limbo: Latinas’ Assessment of Lower Rio Grande Valley Colonias Communities. Public Health Nurs. 2016, 34, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barton, J.; Perlmeter, E.; Marquez, R. Las Colonias in the 21st Century Progress Along the Texas-Mexico Border Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Community Development Economic Opportunity Infrastructure Housing Health Education Methodology. 2016. Available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/cd/pubs/lascolonias.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Sadri, S.R.; Buzzelli, N.R.; Gentile, P.; Billings, A.C. Sports journalism content when no sports occur: Framing athletics amidst the COVID-19 international pandemic. Commun. Sport 2022, 10, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, B.; Rosenstiel, T. The Elements of Journalism, Revised and Updated 4th Edition: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect; Crown Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzelli, N.R.; Gentile, P.; Billings, A.C.; Sadri, S.R. Poaching the News Producers: The Athletic’s Effect on Sports in Hometown Newspapers. J. Stud. 2020, 21, 1514–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neason, A. In a Pandemic, What Is Essential Journalism? Columbia Journalism Review. 2 April 2020. Available online: http://www.cjr.org/analysis/essential-reporting-and-analysis-amid-pandemic.php (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- About USA Today. Available online: https://static.usatoday.com/about/ (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Tang, L.; Bie, B.; Zhi, D. Tweeting about measles during stages of an outbreak: A semantic network approach to the framing of an emerging infectious disease. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, S.; Engel, D.; Cramer, N.; Cowley, W. Automatic keyword extraction from individual documents. In Text Mining: Applications and Theory; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, B.; Gu, T.; Li, J.; Wang, L. Expanding Domain Knowledge Elements for Metro Construction Safety Risk Management Using a Co-Occurrence-Based Pathfinding Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasiya, P.; Okamura, K. Analyzing cybersecurity-related articles in Japan’s english language online newspapers. Proc. Asia-Pac. Adv. Netw. 2019, 48, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, M.; Bobicev, V. What Sentiments Can be Found in Medical Forums? In RANLP 2013; INCOMA Ltd: Shoumen, Bulgaria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, M. A Review of Sentiment Computation Methods with R Packages. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.08319. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MN, USA, 1–4 June 2014; Volume 8, pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Emotions and information diffusion in social media—Sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 29, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, F.; Awan, T.M.; Syed, J.H.; Kashif, A.; Parveen, M. Sentiments and emotions evoked by news headlines of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, R.B.; Estevez, E.; Maguitman, A.; Janowski, T. Examining government-citizen interactions on twitter using visual and sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, Delft, The Netherlands, 30 May–1 June 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasiya, P.; Okamura, K. Investigating COVID-19 news across four nations: A topic modeling and sentiment analysis approach. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 36645–36656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S. Framing responsibility for political issues: The case of poverty. Political Behav. 1990, 12, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrau, V.; Fujarski, S.; Lorenz, H.; Schieb, C.; Blöbaum, B. The impact of health information exposure and source credibility on COVID-19 vaccination intention in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiprasetio, J.; Larasati, A.W. Pandemic Crisis in Online Media: Quantitative Framing Analysis on detik.com’s Coverage of COVID-19. J. Ilmu Sos. Dan Ilmu Polit. 2021, 24, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semetko, H.A.; Valkenburg, P.M. Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. J. Commun. 2000, 50, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. The Role of the Press in the Coronavirus Pandemic is To Provide Truth, Even If That Truth is Grim. 2020. Available online: https://www.poynter.org/newsletters/2020/the-role-of-the-press-in-the-coronavirus-pandemic-is-to-provide-truth-even-if-that-truth-is-grim/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Simonetti, I. Over 360 Newspapers Have Closed Since Just before the Start of the Pandemic. The New York Times. 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/29/business/media/local-newspapers-pandemic.html (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Capps, K. The Hidden Costs of Losing Your City’s Newspaper. Bloomberg.com. 2018. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-30/when-local-newspapers-close-city-financing-costs-rise (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Cui, W.; Liu, S.; Tan, L.; Shi, C.; Song, Y.; Gao, Z.; Qu, H.; Tong, X. TextFlow: Towards Better Understanding of Evolving Topics in Text. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2011, 17, 2412–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Local versus National Papers. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. 1998. Available online: https://www.journalism.org/1998/07/13/local-versus-national-papers/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Divate, M.S. Sentiment analysis of Marathi news using LSTM. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 13, 2069–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afrin, R.; Harun, A.; Prybutok, G.; Prybutok, V. Framing of COVID-19 in Newspapers: A Perspective from the US-Mexico Border. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122362

Afrin R, Harun A, Prybutok G, Prybutok V. Framing of COVID-19 in Newspapers: A Perspective from the US-Mexico Border. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122362

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfrin, Rifat, Ahasan Harun, Gayle Prybutok, and Victor Prybutok. 2022. "Framing of COVID-19 in Newspapers: A Perspective from the US-Mexico Border" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2362. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122362