Effects of Flap Design on the Periodontal Health of Second Lower Molars after Impacted Third Molar Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pre-Surgical Procedure

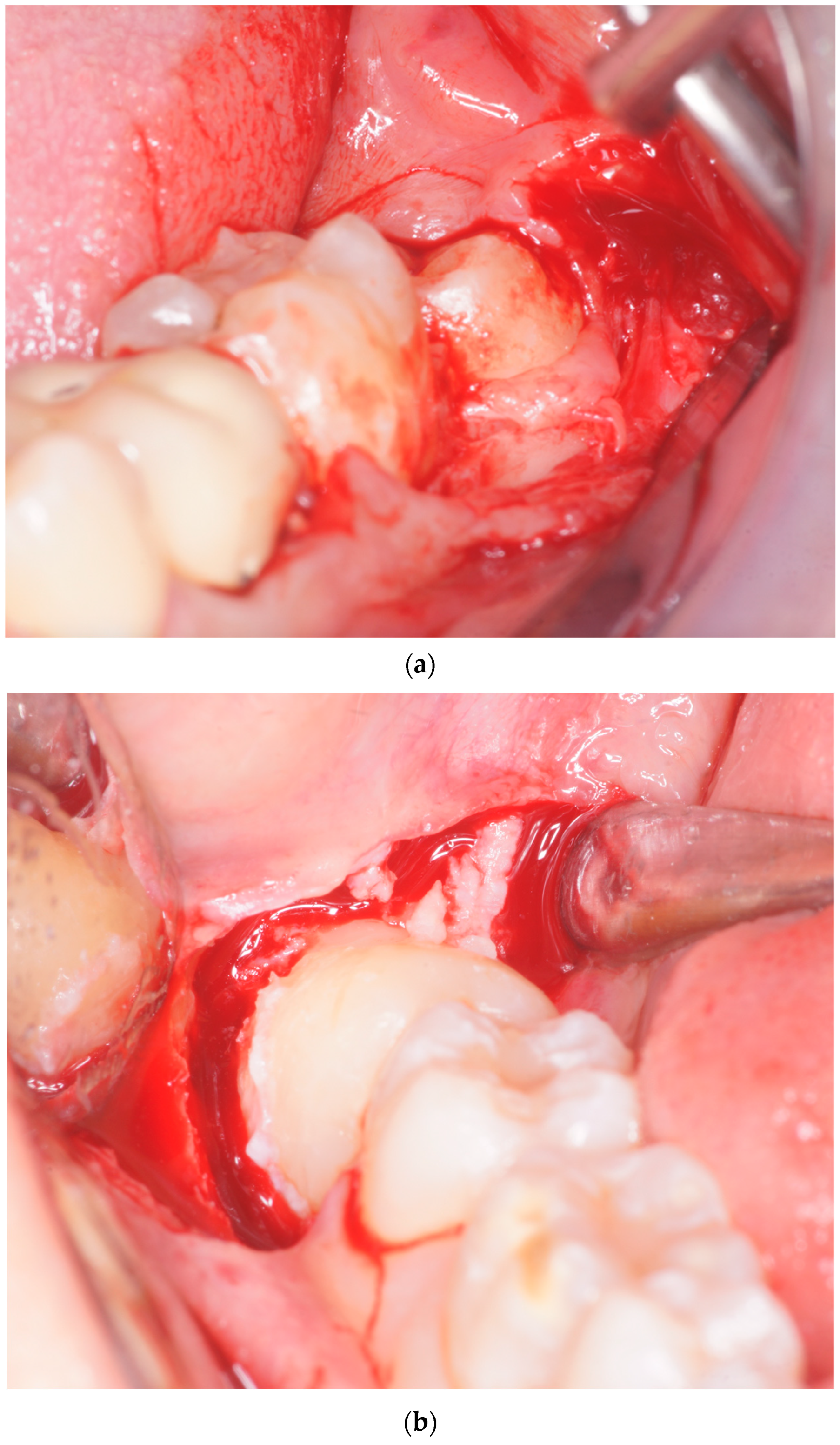

2.2. Surgical Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analysis

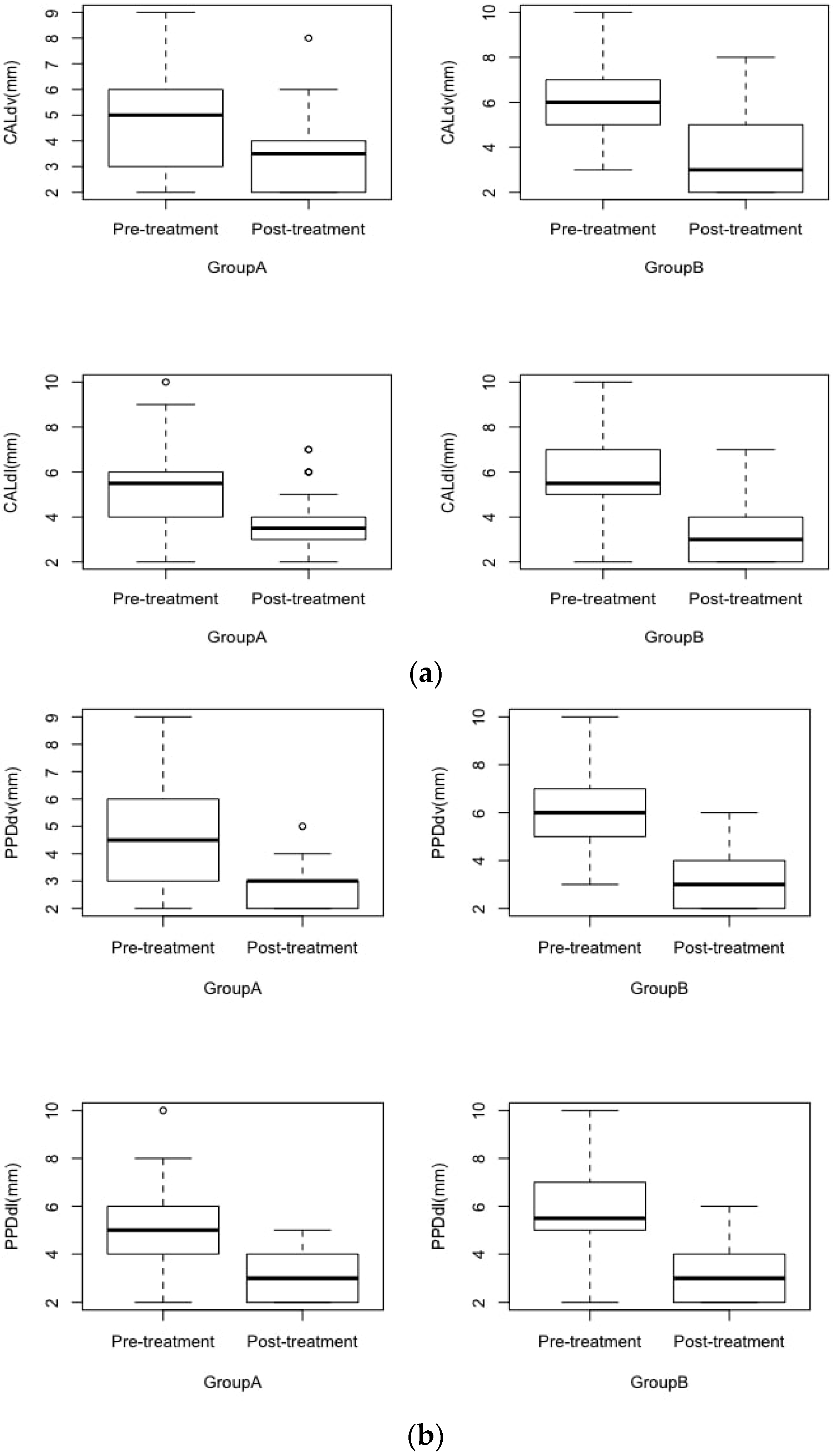

3. Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suarez-Cunqueiro, M.M.; Gutwald, R.; Reichman, J.; Otero-Cepeda, X.L.; Schmelzeisen, R. Marginal flap versus paramarginal flap in impacted third molar surgery: A prospective study. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2003, 95, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiapasco, M.; De Cicco, L. Manuale Illustrato Di Chirurgia Orale–Seconda Edizione; Elsevier Masson: Issy-les-Moulineaux, Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M. Impacted third molars. Br. Dent. J. 1995, 178, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiapasco, M.; De Cicco, L.; Marrone, G. Side effects and complications associated with third molar surgery. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. 1993, 76, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candotto, V.; Oberti, L.; Gabrione, F.; Scarano, A.; Rossi, D.; Romano, M. Complication in third molar extractions. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost Agents. 2019, 33 (Suppl. 1), 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Passarelli, P.C.; Lajolo, C.; Pasquantonio, G.; D’Amato, G.; Docimo, R.; Verdugo, F.; D’Addona, A. Influence of mandibular third molar surgical extraction on the periodontal status of adjacent second molars. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarelli, P.C.; Pasquantonio, G.; D’Addona, A. Management of Surgical Third Lower Molar Extraction and Postoperative Progress in Patients with Factor VII Deficiency: A Clinical Protocol and Focus on This Rare Pathologic Entity. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 2070.e1–2070.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, P.C.; De Angelis, P.; Pasquantonio, G.; Manicone, P.F.; Verdugo, F.; D’Addona, A. Management of Single Uncomplicated Dental Extractions and Postoperative Bleeding Evaluation in Patients With Factor V Deficiency: A Local Antihemorrhagic Approach. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 2280–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.S.; Shah, J.S.; Dudhia, B.B.; Butala, P.B.; Jani, Y.V.; Macwan, R.S. Comparison of panoramic radiograph and cone beam computed tomography findings for impacted mandibular third molar root and inferior alveolar nerve canal relation. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 31, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elter, J.R.; Cuomo, C.J.; Offenbacher, S.; White, R.P. Third molars associated with periodontal pathology in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.P.; Fisher, E.L.; Phillips, C.; Tucker, M.; Moss, K.L.; Offenbacher, S. Visible third molars as risk indicator for increased periodontal probing depth. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, K.W.; Liu, J.K.S.; Lo, E.C.M.; Corbet, E.F.; Leung, W.K. Residual periodontal defects distal to the mandibular second molar 6-36 months after impacted third molar extraction. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizi, R.; Arabion, H.; Gholami, M. How will mandibular third molar surgery affect mandibular second molar periodontal parameters? Dent. Res. J. 2013, 10, 523–526. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D.T.; Dodson, T.B. Risk of periodontal defects after third molar surgery: An exercise in evidence-based clinical decision-making. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2005, 100, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugelberg, C.F. Impacted lower third molars and periodontal health. An epidemiological, methodological, retrospective and prospective clinical, study. Swed. Dent. J. Suppl. 1990, 68, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kırtıloğlu, T.; Bulut, E.; Sümer, M.; Cengiz, İ. Comparison of 2 Flap Designs in the Periodontal Healing of Second Molars After Fully Impacted Mandibular Third Molar Extractions. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 2206–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaeminia, H.; Perry, J.; Nienhuijs, M.E.L.; Toedtling, V.; Tummers, M.; Hoppenreijs, T.J.; Van der Sanden, W.J.; Mettes, T.G. Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016, 8, CD003879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, L.; Kalemaj, Z.; Buti, J.; Baccini, M.; La Marca, M.; Duvina, M.; Tonelli, P. Effect of Surgical Intervention for Removal of Mandibular Third Molar on Periodontal Healing of Adjacent Mandibular Second Molar: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Lee, C.-T.; Hum, L.; Chuang, S.-K. Effect of flap design on periodontal healing after impacted third molar extraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, I.; Simşek, S.; Uğar, D.; Bozkaya, S. Review of flap design influence on the health of the periodontium after mandibular third molar surgery. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2007, 104, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.L.; Carneiro, M.G.; Lavrador, M.A.; Novaes, A.B. Influence of flap design on periodontal healing of second molars after extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2002, 93, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briguglio, F.; Zenobio, E.G.; Isola, G.; Briguglio, R.; Briguglio, E.; Farronato, D.; Shibli, J.A. Complications in surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars in relation to flap design: Clinical and statistical evaluations. Quintessence Int. 2011, 42, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leung, W.K.; Corbet, E.F.; Kan, K.W.; Lo, E.C.M.; Liu, J.K.S. A regimen of systematic periodontal care after removal of impacted mandibular third molars manages periodontal pockets associated with the mandibular second molars. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krausz, A.A.; Machtei, E.E.; Peled, M. Effects of lower third molar extraction on attachment level and alveolar bone height of the adjacent second molar. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 34, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, J.; Mazzaglia, G. Effect of removing an impacted mandibular third molar on the periodontal status of the mandibular second molar. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakey, G.H.; Parker, D.W.; Hull, D.J.; White, R.P., Jr.; Offenbacher, S.; Phillips, C.; Haug, R.H. Impact of removal of asymptomatic third molars on periodontal pathology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 67, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, A.J.P.; Nascimento, L.R.; Costa, M.E.G.; Franz-Montan, M.; Oliveira-Júnior, P.A.; Groppo, F.C. Effects of surgical removal of mandibular third molar on the periodontium of the second molar. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2008, 6, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, A.I.; Gallas-Torreira, M.; López-Ratón, M. Mandibular second molar periodontal healing after impacted third molar extraction in young adults. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 2732–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsos, H.; Korte, J.; Eickholz, P.; Hoffmann, T.; Borchard, R. Surgical removal of third molars and periodontal tissues of adjacent second molars. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, J.O.; Kolsen Petersen, J.; Laskin, D.M. Textbook and Color Atlas of Tooth Impactions; Wiley: Copenhagen, Denmark; Munksgaard, Denmark, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.; Yang, C.; Zheng, J.; Hu, Y. Autogenous bone grafting for treatment of osseous defect after impacted mandibular third molar extraction: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2017, 19, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group A | Group B | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 37.73 ± 17.45 | 35.7 ± 19.98 | 0.6 * |

| Sex | 16 M, 14 F | 13 M, 17 F | 0.6 ** |

| Smoking | 25 N, 5 Y | 24 N, 6 Y | 1 *** |

| Group A | Group B | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | |||||

| dv | dl | dv | dl | dv | dl | dv | dl | |

| PPD (mm) | 4.63 ± 1.61 | 5.07 ± 1.78 | 2.93 ± 0.8 ** | 3.17 ± 0.95 ** | 5.9 ± 1.71 | 5.9 ± 1.96 | 3.2 ± 1.21 ** | 3.27 ± 1.28 ** |

| CAL (mm) | 5.03 ± 1.77 | 5.4 ± 1.92 | 3.6 ± 1.52 ** | 3.73 ± 1.51 ** | 5.97 ± 1.73 | 5.93 ± 2.18 | 3.67 ± 1.77 ** | 3.5 ± 1.63 ** |

| REC (mm) | 0.37 ± 0.67 | 0.67 ± 0.92 ** | 0.23 ± 0.50 | 0.47 ± 0.82 * | ||||

| dv | dl | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | |

| ∆PPD (mm) | 1.7 ± 1.37 | 2.7 ± 1.53 # | 1.9 ± 1.49 | 2.67 ± 1.47 # |

| ∆CAL (mm) | 1.43 ± 1.5 | 2.3 ± 1.44 # | 1.67 ± 1.63 | 2.43 ± 1.59 # |

| ∆REC (mm) | −0.3 ± 0.53 | −0.23 ± 0.5 # | ||

| dv | dl | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | |

| ∆PPD (mm) | 2.519 ± 1.76 | 1.93 ± 1.27 ** | 2.593 ± 1.76 | 2.03 ± 1.26 ** |

| ∆CAL (mm) | 2.333 ± 1.57 | 1.485 ± 1.39 ** | 2.481 ± 1.78 | 1.697 ± 1.45 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Passarelli, P.C.; Lopez, M.A.; Netti, A.; Rella, E.; Leonardis, M.D.; Svaluto Ferro, L.; Lopez, A.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; D’Addona, A. Effects of Flap Design on the Periodontal Health of Second Lower Molars after Impacted Third Molar Extraction. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122410

Passarelli PC, Lopez MA, Netti A, Rella E, Leonardis MD, Svaluto Ferro L, Lopez A, Garcia-Godoy F, D’Addona A. Effects of Flap Design on the Periodontal Health of Second Lower Molars after Impacted Third Molar Extraction. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122410

Chicago/Turabian StylePassarelli, Pier Carmine, Michele Antonio Lopez, Andrea Netti, Edoardo Rella, Marta De Leonardis, Luigi Svaluto Ferro, Andrea Lopez, Franklin Garcia-Godoy, and Antonio D’Addona. 2022. "Effects of Flap Design on the Periodontal Health of Second Lower Molars after Impacted Third Molar Extraction" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122410

APA StylePassarelli, P. C., Lopez, M. A., Netti, A., Rella, E., Leonardis, M. D., Svaluto Ferro, L., Lopez, A., Garcia-Godoy, F., & D’Addona, A. (2022). Effects of Flap Design on the Periodontal Health of Second Lower Molars after Impacted Third Molar Extraction. Healthcare, 10(12), 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122410