Abstract

Antibiotic prophylaxis is used to decrease the bacterial load in the wound to assist the natural host defenses in preventing the occurrence of surgical site infections. The present study aimed to investigate trends in using antibiotic prophylaxis in the surgical ward of a governmental hospital in the Riyadh Region and included collecting data concerning the use of antibiotic prophylaxis from medical electronic records. During 2020, most of the surgical patients received systemic antibiotics (82.40%). The most prescribed antibiotics were ceftriaxone (28.44%) and metronidazole (26.36%). The study also found that most of the patients received antibiotics for seven days or for five days, and only 1.08% of the patients received antibiotics appropriately for a maximum of one day. The present study showed that there was a major problem in selecting the correct antibiotic and in the duration of its use compared with the recommendations of the surgical prophylaxis guideline that was issued by the Saudi Ministry of Health. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve the adherence to the recommendations of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines in order to reduce the occurrence of negative consequences.

1. Introduction

Health care-associated infections (HCAIs) are infections that occur while receiving health care and that develop in health care facilities such as hospitals []. These infections first appear 48 h or more after patient admission or appear within 30 days after receiving health care []. HCAIs include catheter-associated urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, central line-associated bloodstream infections, and surgical site infections (SSIs) []. These infections are common and result in a high mortality rate. In the United States, there are 1.7 million reported HCAIs cases each year, causing about 100,000 deaths [].

Surgical site infection (SSI) is a common hospital-acquired infection that causes significant health problems and results in prolonged hospitalization and increased treatment cost, in addition to increased patient mortality and morbidity []. SSIs are defined as infections that occur within 30 days of a surgery or within 90 days if the surgery includes the insertion of prosthetic material []. The World Health Organization reported that the pooled prevalence of surgical site infections was about 11.2 per 100 surgical patients []. It is estimated that about 10% of hospitalized patients in developing countries acquire HCAIs. Most of these infections are SSIs, which account for approximately 5.6% of surgically admitted patients [].

Antibiotic prophylaxis is one of the measures used to decrease SSI incidence []. Antibiotic prophylaxis is used is to decrease the bacterial load in the wound to assist the natural host defenses in preventing the occurrence of an SSI []. Despite the effectiveness of prophylactic antimicrobials in preventing SSIs, the use of antibiotics is often incorrect []. Bedouch et al. stated that the inappropriate use of antibiotics occurs in 25% to 50% of general elective surgical procedures []. Thus, antibiotic prophylaxis is applied only if the costs and morbidity associated with infection are more than the costs and morbidity associated with antibiotic prophylaxis []. The unnecessary use of antibiotics and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics increase the risk of resistance development []. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be used for a short duration to reduce toxicity and antimicrobial resistance and decrease cost [].

In Saudi Arabia, a few studies have been conducted, showing that antibiotic use patterns for surgical patients have changed over time, but there is still a problem in implementing antimicrobial stewardship practices. Ahmed et al. reported that surgeons in different Riyadh hospitals use preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis incorrectly []. Alghamdi et al. showed that although the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) devised a national antimicrobial stewardship plan to implement antimicrobial stewardship programs in Saudi hospitals, only 26% of hospitals reported the implementation of these programs []. Furthermore, Hammad et al. reported that in Aseer Hospital, the rate of adherence to preoperative and postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines was 36% and 56%, respectively, and that the average adherence rate was 46% []. Tolba et al. stated that there is a significant gap between current surgical antibiotic prophylaxis usage and international/national guidelines, and that there is a need for immediate action to ensure effective guideline adoption and implementation [].

To improve the prescribing of antimicrobial prophylaxis, it is important to know the trends around prescribing antibiotics as well as the adherence to the recommendations of the guidelines. After that, appropriate antimicrobial stewardship practices should be implemented. The World Health Organization stated that the antimicrobial stewardship principles needing to be followed must give due consideration to the national and local context and the structure of the health system when carrying out antimicrobial stewardship activities []. In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Health devised a national antimicrobial stewardship plan that included a surgical prophylaxis guideline in 2018 to be implemented in governmental hospitals [].

Although there are numerous studies on the use of antibiotics in general, there is a lack of studies on the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in our region. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate trends in using antibiotic prophylaxis in the surgical ward of a governmental hospital in the Riyadh Region.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study that included collecting data about the use of antibiotic prophylaxis from medical electronic records. The study was conducted in the surgical ward of a governmental hospital in the Riyadh Region. The hospital has an emergency ward, a maternity ward, and several other specialist wards that serve the public.

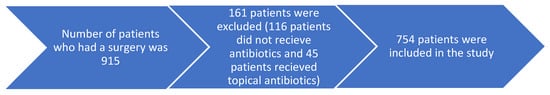

This study included reviewing the medical records of patients who had a surgical procedure in the surgical ward during 2020. So, patients of both genders and from all age groups who visited the surgical ward were included, and patients in other departments were excluded. The total number of antibiotics included tablets, capsules, suspensions, vials, and ampules. Topical antibiotics such as drops and ointments were excluded from this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The number of patients included in this study.

The collected data included the total number of patients who had surgeries and the number and percentage of patients who received surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis. Furthermore, the collected data included the number of different antibiotics that were used and the age and gender of the patients receiving the antibiotics. Moreover, we collected data about the prescribed dosage forms of different antibiotics and the usage duration of these antibiotics.

The data were collected using an Excel sheet and analyzed descriptively. The results were represented as numbers and percentages. The percentages were calculated by dividing each value by the total number and then multiplying the result by 100%. This study was approved by the ethical approval committee of the Saudi Ministry of Health with an IRB registration number H-01-R-053.

3. Results

3.1. Number and Percentage of Patients Who Received Antibiotics

During 2020, 915 patients had surgeries. Most of these patients received systemic antibiotics (82.40%) and less than 18% of these patients did not use antibiotics or topical antibiotics.

3.2. The Most Prescribed Antibiotics in the Surgical Ward

Table 1 shows the number of patients who used different antibiotics during this study. The most prescribed antibiotics were ceftriaxone (28.44%) and metronidazole (26.36%).

Table 1.

Number of different antibiotics prescribed in the surgical ward.

3.3. The Personal Data of the Patients Who Received Antibiotics in the Surgical Ward

Table 2 shows the personal data of the patients who received antibiotics. Most of the patients who received antibiotics were male (61.14%). Most of the patients were in the age groups of 30–39 years (22.81%), 20–29 years (20.29%), and 40–49 years (19.50%).

Table 2.

The personal data of the patients who received antibiotics in the surgical ward.

Table 3 shows the prescribed dosage forms of antibiotics in the surgical ward. Most of the antibiotics were prescribed as a vial or ampule (90.69%), and 8.31% were prescribed as a capsule or tablet.

Table 3.

The prescribed dosage forms of antibiotics in the surgical ward.

Table 4 shows the duration of the use of antibiotics in the surgical ward. More than 69% of the patients received antibiotics for seven days and 19.20% of them used antibiotics for five days. Only 1.08% of the patients received antibiotics for a maximum of one day.

Table 4.

The duration of the use of antibiotics in the surgical ward.

4. Discussion

In this study, antibiotic prophylaxis was administered to 82.40% of cases. The rate of SSIs was very low (less than 0.5%) in the hospital, so almost all of the antibiotics were used as a prophylaxis and not for the treatment of SSIs. Several studies have shown that antibiotics are used excessively and incorrectly for the prevention of SSIs [,,,,,,,,]. This study also showed that the most prescribed antibiotic was ceftriaxone, and that there is a high rate of using broad-spectrum antibiotics. The surgical prophylaxis guideline that was issued by the Ministry of Health and was implemented in governmental hospitals in Saudi Arabia recommended the use of first- or second-generation cephalosporins as a first line for most surgeries and not ceftriaxone []. Similarly to this result, Alemkere reported that ceftriaxone was used excessively and inappropriately in surgical prophylaxis, and that about 19.5% of the patients received a broad-spectrum antibiotic other than the antibiotics that are recommended by the guideline []. Similarly, Mohamoud et al. stated that nearly 84% of the surgical patients were given ceftriaxone, despite the drug not being mentioned in the national guideline []. Moreover, Van Kasteren et al. found that despite the availability of first-choice antibiotics, surgeons had been reported to fail to comply with the guideline recommendations []. They also reported that the barriers to the adherence to the guideline were a lack of awareness of appropriate guidelines, a lack of agreement of surgeons with the guideline recommendations, and logistic limitations in the surgical wards []. On the other hand, Oh et al. reported that the selection of antibiotics for 78.2% of surgical patients was consistent with the guideline recommendations []. Moreover, Al-Azzam et al. found that preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis was employed in almost all surgical departments of hospitals, and the choice of improper antimicrobials was ascribed to drug unavailability [].

This study also found that most of the patients received antibiotics for seven days or for five days, and only 1.08% of the patients received antibiotics appropriately for a maximum of one day. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis should normally be discontinued within 24 h after surgery completion []. The Ministry of Health surgical prophylaxis guideline states that antibiotics should be used once, and if the surgery takes several hours, another dose of antibiotic could be given, but for a maximum of 24 h []. Similarly, Parulekar et al. reported that in a tertiary-care private hospital in India, the appropriateness of antibiotic selection was seen in 68%, and that the percentage of using the appropriate duration of antibiotics was 63% []. Musmar et al. found that in the Northwest Bank of Palestine, only 18.5% of surgical patients had appropriate antibiotic selection, and 31.8% of patients received antibiotics for an appropriate duration []. Moreover, Tourmousoglou et al. stated that for antibiotic prophylaxis in general surgery, the choice of antimicrobial agent was appropriate for about 70% of the patients and the duration of prophylaxis was optimal for about 36% []. Khan et al. reported that more than half (69%) of surgeons who participated in his study thought that antibiotics were overused in surgical procedures []. Furthermore, Oh et al. found that in the surgical ward at a tertiary hospital in Malaysia, prophylactic antibiotics were discontinued within 24 h after the operation in 77% of the cases []. Abdel-Aziz et al. reported that regarding antimicrobial prophylaxis in a tertiary general hospital, the overall use of antibiotics was 89%, but that the use of antibiotics did not match the recommended hospital protocols in more than 53% of cases []. They also reported that prolonged antibiotic use was the most common reason for nonadherence to antimicrobial prophylaxis guidelines (59.3%), followed by the use of an alternative antibiotic to that recommended in the protocol (31.5%) []. Gouvêa et al. conducted a review about the adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and found that the rate of using the correct antibiotic choice ranged from 22% to 95%, and that the rate of the appropriate discontinuation of antibiotics ranged from 5.8% to 91.4% [].

5. Limitation and Strength

The main limitation of the present study is that the rate of surgical site infections was not reported in the hospital, but the physicians informed that the rate of SSIs was less than 0.5%. This, the rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) might have been underestimated. Another limitation is that the diagnosis of the patients and the type of surgeries performed were not mentioned in the electronic files. A strength of this study is that we can estimate the appropriateness of using an antimicrobial agents before a surgery by comparing the commonly prescribed antibiotics and the duration of antibiotics used with the recommendations of the Saudi MOH guideline, because the recommended prophylactic antibiotics for the majority of surgeries were first-generation or second-generation cephalosporin antibiotics, and all of the prophylactic antibiotics should be used as a single dose or for a maximum of 24 h.

6. Conclusions

This study showed that antibiotics were administered to most of the surgical patients to prevent the occurrence of surgical site infections but that there was a major problem in selecting the correct antibiotic and in the duration of use compared with the recommendations of the surgical prophylaxis guideline issued by the Saudi Ministry of Health. There is an urgent need to improve the adherence to the recommendations of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines to reduce the occurrence of negative consequences. Moreover, it is important to encourage all healthcare providers to attend workshops and to be trained in the appropriate use of antibiotics for surgical patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and M.B.; methodology, N.A.; software, N.A.; validation, N.A., M.B., A.H., and A.K.; formal analysis, N.A.; investigation, N.A.; resources, N.A.; data curation, N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and A.K.; visualization, N.A.; supervision, A.H. and A.K.; project administration, N.A. and M.B.; funding acquisition, N.A. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (IFPSAU-2021/03/19201).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ethical approval committee of the Saudi Ministry of Health with an IRB registration number H-01-R-053.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (IFPSAU-2021/03/19201).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haque, M.; Sartelli, M.; McKimm, J.; Abu Bakar, M. Health care-associated infections—An overview. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 2321–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Types of Healthcare-Associated Infections. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/infectiontypes.html (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Klevens, R.M.; Edwards, J.R.; Richards, C.L., Jr.; Horan, T.C.; Gaynes, R.P.; Pollock, D.A.; Cardo, D.M. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007, 122, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kefale, B.; Tegegne, G.T.; Degu, A.; Molla, M.; Kefale, Y. Surgical site infections and prophylaxis antibiotic use in the surgical ward of public hospital in Western Ethiopia: A hospital-based retrospective cross-sectional study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 3627–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegranzi, B.; Bagheri Nejad, S.; Combescure, C.; Graafmans, W.; Attar, H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. Available online: https://www.who.int/gpsc/global-guidelines-web.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Gouvêa, M.; Novaes, C.D.O.; Pereira, D.M.T.; Iglesias, A.C. Adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis: A review. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 19, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Allen, J.; Barlow, G. Antibiotic prophylaxis. Surgery 2012, 30, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S.M.; Roozbeh, F.; Behmanesh, F.; Alavi, L. Antibiotics use patterns for surgical prophylaxis site infection in different surgical wards of a teaching hospital in Ahvaz, Iran. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2014, 7, e12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedouch, P.; Labarère, J.; Chirpaz, E.; Allenet, B.; Lepape, A.; Fourny, M.; Pavese, P.; Girardet, P.; Merloz, P.; Saragaglia, D.; et al. Compliance with guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip replacement surgery: Results of a retrospective study of 416 patients in a teaching hospital. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2004, 25, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herawati, F.; Yulia, R.; Hak, E.; Hartono, A.H.; Michiels, T.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Avanti, C. A retrospective surveillance of the antibiotics prophylactic use of surgical procedures in private hospitals in Indonesia. Hosp. Pharm. 2019, 54, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzler, M.J.; Berbari, E.; Osmon, D.R. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in adults. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.J.; Jalil, M.A.; Al-Shdefat, R.I.; Tumah, H.N. The practice of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis and the adherence to guideline in Riyadh hospitals. Bull. Environ. Parmacology Life Sci. 2015, 5, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, S.; Berrou, I.; Aslanpour, Z.; Mutlaq, A.; Haseeb, A.; Albanghali, M.; Hammad, M.A.; Shebl, N. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Saudi hospitals: Evidence from a national survey. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, M.A.; AL-Akhali, K.M.; Mohammed, A.T. Evaluation of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in aseer area hospitals in kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Phys. Clin. Sci. 2013, 6, 1–7. Available online: https://www.arpapress.com/Volumes/JPCS/Vol6/JPCS_6_01.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Tolba, Y.Y.A.; El-Kabbani, A.O.; Al-Kayyali, N.S. An observational study of perioperative antibiotic-prophylaxis use at a major quaternary care and referral hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2018, 12, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Policy Guidance on Integrated Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025530 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Saudi Ministry of Health. Surgical Prophylaxis Guidelines. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/CCC/healthp/regulations/Documents/National%20Antimicrobial%20%20Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Bennett, N.J.; Bull, A.L.; Dunt, D.R.; Russo, P.L.; Spelman, D.W.; Richards, M.J. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in smaller hospitals. ANZ J. Surg. 2006, 76, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, E.M.; Coello, R.; Sedgwick, J.; Ward, V.; Wilson, J.; Charlett, A.; Ward, B.; Pearson, A. A national surveillance scheme of hospital associated infections in England. J. Hosp. Infect. 2000, 46, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennessy, B.G.; O’sullivan, M.J.; Fulton, G.J.; Kirwan, W.O.; Redmond, H.P. Prospective study of use of perioperative antimicrobial therapy in general surgery. Surg. Infect. 2006, 7, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiyama, Y.; Kusachi, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Arima, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Nagao, J.; Saida, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Sato, J. Questionnaire on perioperative antibiotic therapy in 2003: Postoperative prophylaxis. Surg. Today 2006, 36, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Y.A.; Hong, L.C.; Prasannan, S. Appropriate antibiotic administration in elective surgical procedures. Asian J. Surg. 2005, 28, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrajati, R.; Vlček, J.; Kolar, M.; Pípalová, R. Survey of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis in Czech republic. Pharm. World Sci. 2005, 27, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castella, A.; Charrier, L.; Di Legami, V.; Pastorino, F.; Farina, E.C.; Argentero, P.A.; Zotti, C.M.; Piemonte Nosocomial Infection Study Group. Surgical site infection surveillance: Analysis of adherence to recommendations for routine infection control practices. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2006, 27, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliotti, C.; Ravaglia, F.; Resi, D.; Moro, M.L. Quality of local guidelines for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2004, 56, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, A.H.; Parvez, F.M.; Vu, T.; Hai, H.H.; Bich, N.N.; Le Thi, A.T.; Le Thi, T.H.; Thanh, N.H.; Viet, T.V.; Archibald, L.K.; et al. Prevalence of surgical-site infections and patterns of antimicrobial use in a large tertiary care hospital. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2002, 23, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemkere, G. Antibiotic usage in surgical prophylaxis: A prospective observational study in the surgical ward of Nekemte referral hospital. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamoud, S.A.; Yesuf, T.A.; Sisay, E.A. Utilization assessment of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis at Ayder Referral hospital, Northern Ethiopia. J. Appl. Pharm. 2016, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kasteren, M.E.; Kullberg, B.J.; de Boer, A.S.; Mintjes-de Groot, J.; Gyssens, I.C. Adherence to local hospital guidelines for surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis: A multicentre audit in Dutch hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, A.L.; Goh, L.M.; Nik Azim, N.A.; Tee, C.S.; Shehab Phung, C.W. Antibiotic usage in surgical prophylaxis: A prospective surveillance of surgical wards at a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 8, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzam, S.I.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Mhaidat, N.M.; Haddadin, R.D.; Masadeh, M.M.; Tumah, H.N.; Magableh, A.; Maraqa, N.K. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis practice and guideline adherence in Jordan: A multi-centre study in Jordanian hospitals. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2012, 6, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkind, A.R.; Rao, K.C. Antiobiotic prophylaxis to prevent surgical site infections. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 83, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parulekar, L.; Soman, R.; Singhal, T.; Rodrigues, C.; Dastur, F.D.; Mehta, A. How good is compliance with surgical antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines in a tertiary care private hospital in India? A prospective study. Indian J. Surg. 2009, 71, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Musmar, S.M.; Baba, H.; Owais, A. Adherence to guidelines of antibiotic prophylactic use in surgery: A prospective cohort study in North West Bank, Palestine. BMC Surg. 2014, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourmousoglou, C.E.; Yiannakopoulou, E.C.; Kalapothaki, V.; Bramis, J.; St Papadopoulos, J. Adherence to guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in general surgery: A critical appraisal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Ahmed, N.; Zafar, S.; Khan, F.U.; Saqlain, M.; Kamran, S.; Rahman, H. Audit of antibiotic prophylaxis and adherence of surgeons to standard guidelines in common abdominal surgical procedures. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aziz, A.; El-Menyar, A.; Al-Thani, H.; Zarour, A.; Parchani, A.; Asim, M.; El-Enany, R.; Al-Tamimi, H.; Latifi, R. Adherence of surgeons to antimicrobial prophylaxis guidelines in a tertiary general hospital in a rapidly developing country. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 2013, 842593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouvêa, M.; Novaes, C.D.O.; Iglesias, A.C. Assessment of antibiotic prophylaxis in surgical patients at the Gaffrée e Guinle university hospital. Rev. Colégio Bras. Cir. 2016, 43, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).