The Use of an Electronic Painting Platform by Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia Experience Distress

1.2. Use of Mobile Applications in Stress Management

1.3. Painting in Stress Management

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Registration

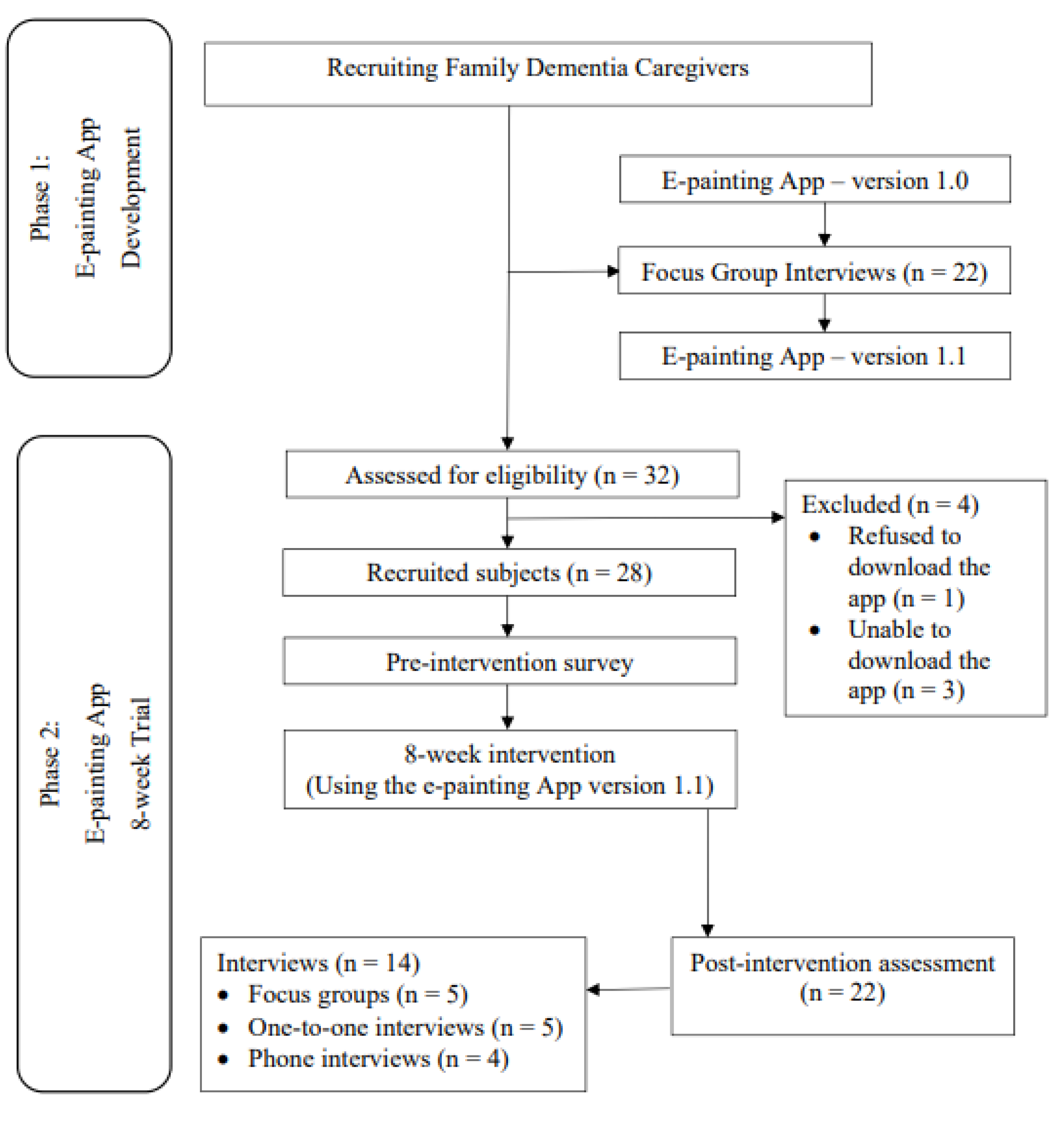

2.2. Design

2.3. Sampling and Sample Size

2.4. Participants and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Recruitment and Consent

2.6. Data Collection

Recruitment Rate, Completion Rate, and Retention Rate

2.7. Ethical Issues

2.8. Quantitative Survey

2.8.1. Background Information

2.8.2. Psychosocial Assessments

Caregivers’ Burden

Self-Rated Health (SRH)

Depressive Symptoms

Instrumental and Emotional Social Support

2.9. Focus Group Interviews

- What functions do you prefer in the e-painting app?

- What kind of training do you need before using the e-painting app?

- What kinds of follow-up actions do you prefer after using the e-painting app?

- What do you think about this e-painting mobile app?

- What do you like or dislike most about this app?

- What features could be added to this app?

- Do you enjoy using the e-painting app? And in what way?

2.10. Statistical Analysis

2.11. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1 Result: Preferences with Regard to Features and Expected Training

“Does the app have music, like background music? … Yeah, that’s my way of relaxing, music … is one of the methods.”(Participant 1, February 1, L557; 561)

“For example, you can have colour filling, or some demonstrations for app users, then you can follow and imitate the drawing.”(Participant 2, February 1, L552–553)

“Yeah, (a mood assessment) could tell which level you are. You can have some suggestions (from the assessment results) such as what things you can do next, whether you can relax a bit, find someone to talk with, etc.”(Participant 28, April 20, L178–180)

3.2. Phase 2 Result: Demographic Information

3.3. Phase 2 Result: Feasibility of the Use of the Electronic Painting Platform

3.4. Phase 2 Result: Acceptance of this E-Painting App by the FCPWD

3.5. Phase 2 Result: Preliminary Efficacy of the Intervention on Psychosocial Well-Being

3.6. Phase 2 Result: Qualitative Results

“Enjoy! It [the e-painting app] is very easy to use.”(Participant 36, L144–147)

“This is fun … this one [the e-painting app] is fun.”(Participant 5, L92–95)

“I looked at what the others drew … sometimes, when I looked at those paintings, I found it was very interesting … it was fun.”(Participant 36, L161–164)

“I want to draw, I want to draw well, but I cannot draw well. It is okay not to draw well, you can point to the ‘white’ and then they will vanish. See? This is really good.”(Participant 5, L60–63)

“But it is good to use the mobile phone to draw the paintings, that is, no matter how you do this … you could still draw the paintings … it is convenient [Another participant agreed and said—convenient!], the advantage here is its convenience.”(Participant 29), L21–252)

“Whenever I feel annoyed, I used to throw objects or tear things apart … but now, err. Painting can soothe my bad mood…. I see it as a way to let go of bad feelings”(Participant 5, L55–59)

“Yes … yes … this is a pressure releasing tool.’(Participant 5, L60–63)

“Whenever I paint, I feel like I’m brushing away all the negative events.”(Participant 19, L282–284)

“I became happy when I drew the paintings, that is, say … when you are drawing for two hours, you forget everything in these two hours … you do not remember the other things. You are in the paintings.”(Participant 29, L336–337)

“At the beginning, I drew more, then recently I drew few paintings … my emotions have become stable these days … ah …. Those paintings … make a person more positive, and make the emotions better.”(Participant 29, L30–32)

“I really find e-painting helpful.”(Participant 19, L270–272)

“I wanna talk to someone but when no one is there for me … I will then try e-painting”(Participant 7, L621)

“[T]hen I feel … happier. No matter whether I write this correctly or not, let people hear what I say … then someone will respond to me, someone will read my words.’ ‘Anyway … there is some communication here.”(Participants 25 and 26, L93–95)

“Because of the group [in the app], whatever you put into the chat, the other caregivers can read it. That is, you know, you have already communicated with others.”(Participant 26, L110–111)

“It is better to draw the paintings by yourself, you can look at others’ paintings, but you should participate … this is better, then you interact with others. … that is, we are interacting, like this … in fact, we are the same group of people … that is, we are facing similar challenges.”(Participant 29, L44–49, 52)

“[S]tigma … I don’t have the guts to tell others….’(Participant 3, L383–386 & L397–400)

“It is very harsh…. [I am] physically, psychologically drained.”(Participant 8, L177–179)

“Insomnia … I’m losing my appetite and didn’t sleep well … err … not sure if I’m depressive coz I have lost interest in everything.”(Participant 1, L378–381).

“Istay at home almost 24 h/day and don’t go out…. I am scared of being alone at home coz … I feel very unhappy.”(Participant 17, L34–37)

“Do you know (we) caregivers like to get someone to talk?”(Participant 5, L99–101)

“Yes, why do we like to be together? In fact, we like something simple. Caregivers only need to ventilate, or listen to others’ experiences; this is for our reference. If I know that this caregiver is in a low mood, I will comfort him/her. Err … this is very important. No one supports us!”(Participant 5, L113–117)

“E-painting does not seem to help alleviate my stress.”(Participant 7, May 20, L173–175)

“I don’t like painting … it doesn’t help.”(Participant 8, May 20, L354–357)

“If you ask me, I like the ‘announcements’—announcements of news. Because, in the group, everyone is reading the messages from this … that is, we get some advice/directions.”(Participant 25, L84–85)

“I think the announcements … should be … about showing us how to take care of the illness [dementia], that is, the sick [person with dementia], to recognize the sick person. Because in many occasions, their emotions have … significantly changed.”(Participant 13, L184–186)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Week 1–A person I like |

| Week 2–A plant I like |

| Week 3–A place I like |

| Week 4–An animal I like |

| Week 5–A task I often do |

| Week 6–Something I want to do when I am free |

| Week 7–A place I want to go to when I am free |

| Week 8–Some food I want to eat |

References

- World Health Organization. Dementia: Number of people affected to triple in next 30 years. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein, K.; Gaugler, J.E.; Zahodne, L.; Stern, Y. The heterogeneous course of depressive symptoms for the dementia caregiver. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2014, 78, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferrara, M.; Langiano, E.; Di Brango, T.; De Vito, E.; Di Cioccio, L.; Bauco, C. Prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in Alzheimer caregivers. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, X.; Guo, Q.; Luo, J.; Li, F.; Ding, D.; Zhao, Q.; Hong, Z. Anxiety and depression symptoms among caregivers of care-recipients with subjective cognitive decline and cognitive impairment. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, M.; Dorstyn, D.; Ward, L.; Prentice, S. Alzheimers’ disease and caregiving: A meta-analytic review comparing the mental health of primary carers to controls. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 22, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.L.; Lau, B.H.P.; Wong, P.W.C.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Lou, V.W.; Chan, G.M.Y.; Schulz, R. Multicomponent intervention on enhancing dementia caregiver well-being and reducing behavioral problems among Hong Kong Chinese: A translational study based on REACH II. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.; Mullan, J.; Semple, S.; Skaff, M. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-Y. Predictors of emotional strain among spouse and adult child caregivers. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2006, 47, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sohn, B.K.; Lee, H.; Seong, S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.-Y. Impact of behavioral symptoms in dementia patients on depression in daughter and daughter-in-law caregivers. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Erno, A.; Shea, D.G.; Femia, E.E.; Zarit, S.H.; Parris, S.M.A. The caregiver stress process and health outcomes. J. Aging Health 2007, 19, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slayton, S.C.; D’Archer, J.; Kaplan, F. Outcome Studies on the Efficacy of Art Therapy: A Review of Findings. Art Ther. 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Vidales, E.; Soto-Perez, F.; Perea-Bartolome, M.V.; Franco-Martin, M.A.; Munoz-Sanchez, J.L. Online interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2017, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choe, S. An exploration of the qualities and features of art apps for art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2014, 41, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E.; Greene, C.; Hoffman, J.; Nguyen, T.; Wald, L.; Schmidt, J.; Ramsey, K.; Ruzek, J. Preliminary evaluation of PTSD Coach, a smartphone app for post-traumatic stress symptoms. Mil. Med. 2014, 179, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Richardson, B.; Little, K.; Teague, S.; Hartley-Clark, L.; Capic, T.; Khor, S.; Cummins, R.A.; Olsson, C.A.; Hutchinson, D. Efficacy of a Smartphone App Intervention for Reducing Caregiver Stress: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e17541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, L.; Morabito, D.; Ladakakos, C.; Schreier, H.; Knudson, M.M. The effectiveness of art therapy interventions in reducing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in pediatric trauma patients. Art Ther. 2001, 18, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpavičiūtė, S.; Macijauskienė, J. The impact of arts activity on nursing staff well-being: An intervention in the workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, M.S.; Kaimal, G.; Koffman, R.; DeGraba, T.J. Art therapy for PTSD and TBI: A senior active duty military service member’s therapeutic journey. Arts Psychother. 2016, 49, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolwerk, A.; Mack-Andrick, J.; Lang, F.R.; Dörfler, A.; Maihöfner, C. How art changes your brain: Differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmire, D.A.; Gorham, S.R.; Rankin, N.E.; Grimm, D.R. The influence of art making on anxiety: A pilot study. Art Ther. 2012, 29, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curr, N.A.; Kasser, T. Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? Art Ther. 2005, 22, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, M.; Whitaker, R. The image, mentalisation and group art psychotherapy. Int. J. Art Ther. 2007, 12, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussak, D. Effects of art therapy with prison inmates: A follow-up study. Arts Psychother. 2006, 33, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusted, J.; Sheppard, L.; Waller, D. A multi-centre randomized control group trial on the use of art therapy for older people with dementia. Group Anal. 2006, 39, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camic, P.M.; Baker, E.L.; Tischler, V. Theorizing how art gallery interventions impact people with dementia and their caregivers. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camic, P.M.; Tischler, V.; Pearman, C.H. Viewing and making art together: A multi-session art-gallery-based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondro, A.; Connell, C.M.; Li, L.; Reed, E. Retaining identity: Creativity and caregiving. Dementia 2020, 19, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, M.R.; Spencer, S.K.; Barnett, M.; Reynolds, N.C.; Madan-Swain, A. Legacy Artwork in Pediatric Oncology: The Impact on Bereaved Caregivers’ Psychological Functioning and Grief. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, H.; Toll, A. A Mountainscape of varied perspectives [Un paysage de montagne aux perspectives variées]. Can. J. Art Ther. 2021, 34, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, G.; Walker, M.S.; Herres, J.; Berberian, M.; DeGraba, T.J. Examining associations between montage painting imagery and symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress among active-duty military service members. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2022, 16, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, R. Justifying Sample Size for a Feasibility Study: Research Design Service; NIHR: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.Y.-M.; Ho, A.H.-Y.; Luo, H.; Wong, G.H.-Y.; Lau, B.H.-P.; Lum, T.Y.-S.; Cheung, K.S. Validating a Cantonese short version of the Zarit Burden Interview (CZBI-Short) for dementia caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, O.; Manderbacka, K. Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand. J. Soc. Med. 1996, 24, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Tam, W.W.; Wong, P.T.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Stuck, A.E.; Silliman, R.A.; Ganz, P.A.; Clough-Gorr, K.M. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: Psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leung, L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Y.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; Liang, T.N.; Leung, D.; Chai, A.J.; Leung, A.Y.M. ‘Am I entitled to take a break in caregiving?’: Perceptions of leisure activities of family caregivers of loved ones with dementia in China. Dement. Int. J. Soc. Res. Pract. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Mueller, J.; Hennings, J.; Caress, A.; Jay, C. Recommendations for Developing Support Tools with People Suffering from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Co-Design and Pilot Testing of a Mobile Health Prototype. JMIR Hum. Factors 2020, 7, e16289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konečni, V.J. Emotion in Painting and Art Installations. Am. J. Psychol. 2015, 128, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Witte, M.D.; Lindelauf, E.; Moonen, X.; Stams, G.J.; Hooren, S.V. Music Therapy Interventions for Stress Reduction in Adults with Mild Intellectual Disabilities: Perspectives from Clinical Practice. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, W.; Epps, F.; Kovaleva, M.; Bridwell, L.; Tate, R.C.; Dorbin, C.D.; Hepburn, K. Photojournalism-Based Intervention Reduces Caregiver Burden and Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Family Caregivers. J. Holist. Nurs. 2019, 37, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.Y.I. Challenges and Recommendations for the Deployment of Information and Communication Technology Solutions for Informal Caregivers: Scoping Review. JMIR Aging 2020, 3, e20310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8 | 28.6 |

| Female | 20 | 71.4 | |

| Age | Below 60 | 11 | 39.3 |

| 60 or above | 17 | 60.7 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 2 | 7.1 |

| Married | 26 | 92.9 | |

| Places where Educated | Hong Kong | 25 | 89.3 |

| China or Others | 3 | 10.7 | |

| Highest Academic Qualification | Primary or below | 4 | 14.3 |

| Secondary | 14 | 50.0 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree or above | 10 | 35.7 | |

| Employment Status | Retired/Unemployed | 22 | 78.6 |

| Employed Full-time | 4 | 14.3 | |

| Employed Part-time | 2 | 7.1 | |

| Occupation | Managers and Administrators | 3 | 10.7 |

| Professionals # | 8 | 28.6 | |

| Non-professionals # | 9 | 32.1 | |

| Unclassifiable/Others | 8 | 28.6 | |

| Monthly Income(in Hong Kong dollars) | <$2000 | 12 | 42.9 |

| $2001–12,000 | 5 | 17.8 | |

| ≥$12,001 | 11 | 39.3 | |

| Number of years spent providing care to persons with dementia | <3 years | 12 | 42.9 |

| 3 to 5 years | 5 | 17.9 | |

| >5 to 10 years | 8 | 28.6 | |

| >10 years | 3 | 10.6 | |

| Times | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Frequency of logins | |

| 1 to 8 | 18 (64.3%) |

| 9 to 16 | 8 (28.6%) |

| >16 | 2 (7.1%) |

| Frequency of sharing of paintings | |

| 0 | 8 (28.6%) |

| 1 to 8 | 16 (57.1%) |

| 9 to 16 | 3 (10.7%) |

| >16 | 1 (3.6%) |

| Psychosocial Well-Being | Pre | Post | Mean Difference | t | p | Cohen’s D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | (SD) | ||||

| CZBI-Short | 30.71 | 7.15 | 33.57 | 6.89 | 2.86 (4.87) | 3.10 | 0.004 | 0.41 |

| SRH | 3.14 | 0.93 | 3.18 | 0.77 | 0.04 (0.92) | 0.21 | 0.839 | 0.05 |

| PHQ-9 | 15.25 | 4.95 | 15.61 | 5.03 | 0.36 (3.20) | 0.59 | 0.560 | 0.07 |

| mMOS-SS | 20.14 | 6.00 | 21.32 | 5.48 | 1.18 (5.31) | 1.17 | 0.251 | 0.21 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leung, A.Y.M.; Cheung, T.; Fong, T.K.H.; Zhao, I.Y.; Kabir, Z.N. The Use of an Electronic Painting Platform by Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050870

Leung AYM, Cheung T, Fong TKH, Zhao IY, Kabir ZN. The Use of an Electronic Painting Platform by Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study. Healthcare. 2022; 10(5):870. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050870

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeung, Angela Y. M., Teris Cheung, Tommy K. H. Fong, Ivy Y. Zhao, and Zarina N. Kabir. 2022. "The Use of an Electronic Painting Platform by Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study" Healthcare 10, no. 5: 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050870

APA StyleLeung, A. Y. M., Cheung, T., Fong, T. K. H., Zhao, I. Y., & Kabir, Z. N. (2022). The Use of an Electronic Painting Platform by Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study. Healthcare, 10(5), 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050870