Maternal Confidence and Parenting Stress of First-Time Mothers in Taiwan: The Impact of Sources and Types of Social Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Maternal Confidence Questionnaire

2.2.2. Social Support Rating Scale

2.2.3. Parenting Stress Index: Short Form

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Differences between Sources and Types of Social Support

3.3. Correlational Analyses

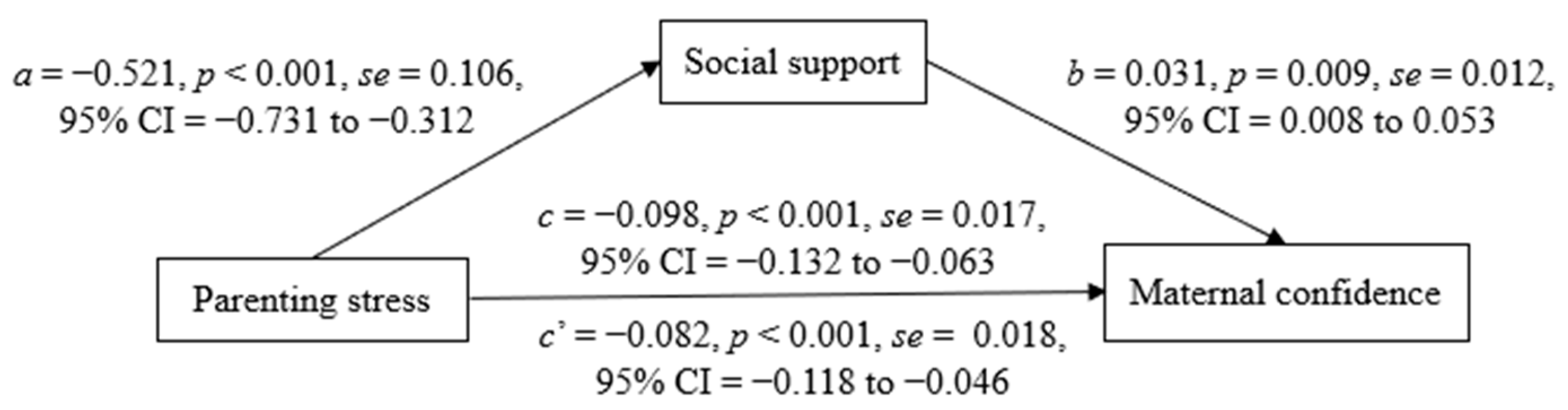

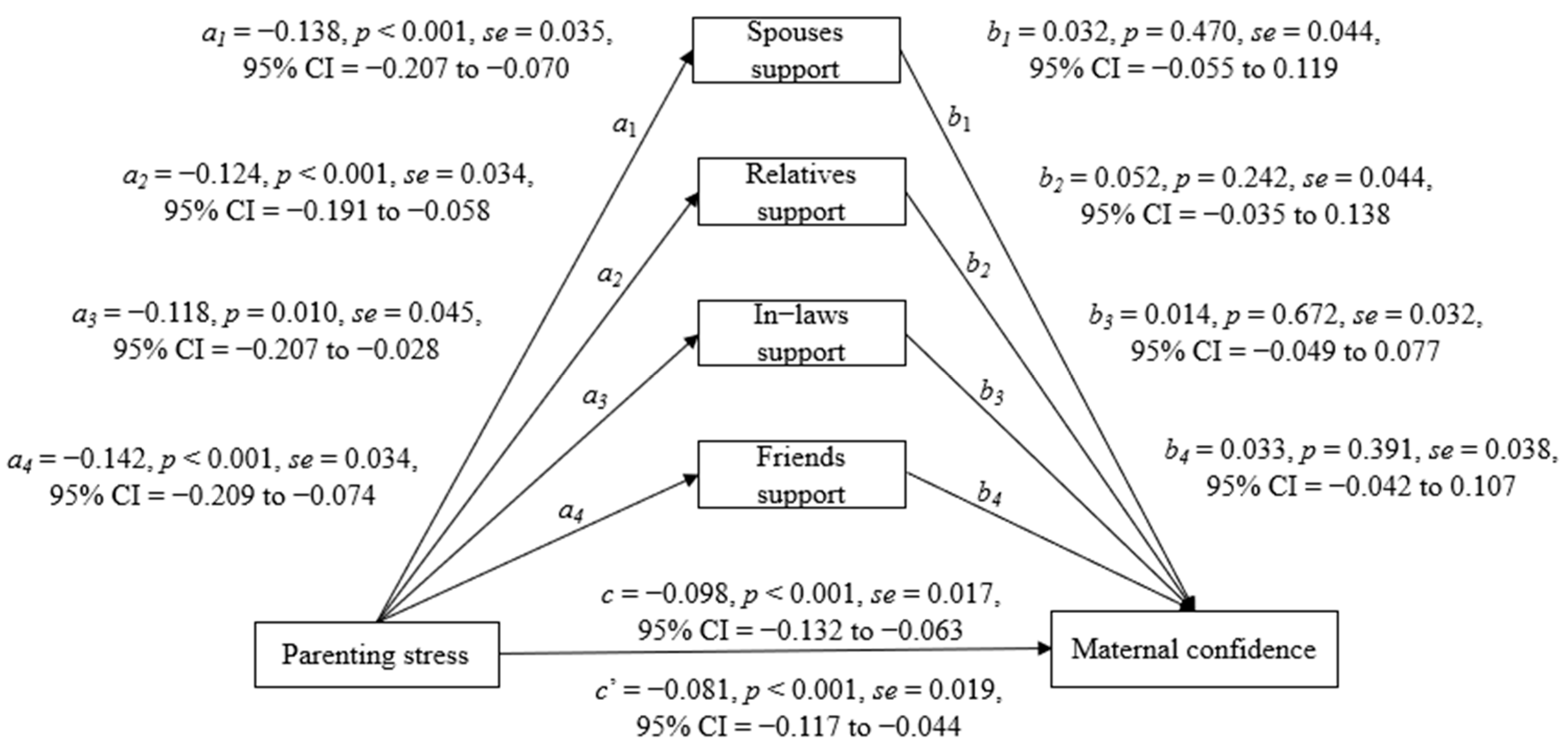

3.4. Tests of Mediation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, A.M. Transition to motherhood. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.L.; Pallant, J.F.; Negri, L.M. Anxiety and stress in the postpartum: Is there more to postnatal distress than depression? BMC Psychiatry 2006, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gavin, N.I.; Gaynes, B.N.; Lohr, K.N.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Gartlehner, G.; Swinson, T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saur, A.M.; Dos Santos, M.A. Risk factors associated with stress symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum: Integrative literature review. Women Health 2021, 61, 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; McCabe, J.E. Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Yeh, Y.P.; Hsieh, Y.S. Effects of maternal confidence and competence on maternal parenting stress in newborn care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arante, F.O.; Tabb, K.M.; Wang, Y.; Faisal-Cury, A. The relationship between postpartum depression and lower maternal confidence in mothers with a history of depression during pregnancy. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, L.K. Further psychometric testing and use of the Maternal Confidence Questionnaire. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2005, 28, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Nguyen, Q.V.; Van Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, N.M.; Chung, T.M.T.; Trinh, H.P.; Yabe, J.; Sasaki, H.; Yasumura, S. Associations of psychosocial factors with maternal confidence among Japanese and Vietnamese mothers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korja, R.; Latva, R.; Lehtonen, L. The effects of preterm birth on mother–infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two years. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaelzadeh Saeieh, S.; Rahimzadeh, M.; Yazdkhasti, M.; Torkashvand, S. Perceived social support and maternal competence in primipara women during pregnancy and after childbirth. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2017, 5, 408–416. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.-L.; Sun, K.; Chan, S.W.-C. Social support and parenting self-efficacy among Chinese women in the perinatal period. Midwifery 2014, 30, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Chan, S.W.-C.; Chong, Y.S.; He, H.-G. Predictors of maternal parental self-efficacy among primiparas in the early postnatal period. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 1604–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S. Stress, social support and disorder. In The Meaning and Measurement of Social Support; Veiel, H.O.F., Baumann, U., Eds.; Hemisphere Publishing Corp: London, UK, 1992; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy-Warren, P.; McCarthy, G.; Corcoran, P. First-time mothers: Social support, maternal parental self-efficacy and postnatal depression. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, E.N.; Creedy, D.K.; St John, W.; Brown, C. Maternal role development: The impact of maternal distress and social support following childbirth. Midwifery 2011, 27, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Kalibatseva, Z. Are “Superwomen” without social support at risk for postpartum depression and anxiety? Women Health 2021, 61, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Zain, N.; Low, W.-Y.; Othman, S. Impact of maternal marital status on birth outcomes among young Malaysian women: A prospective cohort study. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premji, S.S.; Pana, G.; Currie, G.; Dosani, A.; Reilly, S.; Young, M.; Hall, M.; Williamson, T.; Lodha, A.K. Mother’s level of confidence in caring for her late preterm infant: A mixed methods study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e1120–e1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, M.; Okada, T.; Aleksic, B.; Morikawa, M.; Kubota, C.; Nakamura, Y.; Shiino, T.; Yamauchi, A.; Uno, Y.; Murase, S. Social support helps protect against perinatal bonding failure and depression among mothers: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, X.; Morrell, J.; Watts, K. Changes in maternal self-efficacy, postnatal depression symptoms and social support among Chinese primiparous women during the initial postpartum period: A longitudinal study. Midwifery 2018, 62, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sepa, A.; Frodi, A.; Ludvigsson, J. Psychosocial correlates of parenting stress, lack of support and lack of confidence/security. Scand. J. Psychol. 2004, 45, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonds, D.D.; Gondoli, D.M.; Sturge-Apple, M.L.; Salem, L.N. Parenting stress as a mediator of the relation between parenting support and optimal parenting. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2002, 2, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sato, Y. Relationships of social support, stress, and health among immigrant Chinese women in Japan: A cross-sectional study using structural equation modeling. Healthcare 2021, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G. Self and other: A Chinese perspective on interpersonal relationships. In Communication in Personal Relationships across Cultures; Gudykunst, W.B., Ting-Toomey, S., Nishida, T., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Ariizumi, Y. Close interpersonal relationships among Japanese. In Indigenous and Cultural Psychology; Kim, U., Yang, K.-S., Hwang, K.-K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Household Registration, Ministry of the Interior. Statistics of Population. Available online: https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346 (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Parker, S.J.; Zahr, L.K.; Cole, J.G.; Brecht, M.-L. Outcome after developmental intervention in the neonatal intensive care unit for mothers of preterm infants with low socioeconomic status. J. Pediatr. 1992, 120, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P. Relationships among Mental Health, Social Support, Home Enviroment and Toddlers’ Difficult Temperament in Vietnamese Mothers: A Comparison with Taiwanese; National Cheng Kung University: Taiwan, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Hoberman, H.M. Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL); APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, B. Parenting Stress Index—Chinese Version; Psychological Publishing Corp.: Taiwan, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index, 3rd ed.; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.R.; Lin, P.-C.; Lee, P.-H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chen, S.-R. The relationship between postpartum depression and maternal confidence, sleep quality and infants′ sleep quality. New Taipei J. Nurs. 2021, 23, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-F.; Tsai, M.-J. Correlation among parenting stress, social support, and the satisfaction with life in married career women with infants aged years. J. Early Child. Educ. 2020, 31, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L. The transition to parenthood: Stress, resources, and gender differences in a Chinese society. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 34, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallis, S.; Skouteris, H.; McCabe, M.; Milgrom, J. The transition to motherhood: Towards a broader understanding of perinatal distress. Women Birth 2014, 27, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, E.; Tsuchiya, M.; Maehara, K.; Iwata, H.; Sakajo, A.; Tamakoshi, K. Fatigue, depression, maternal confidence, and maternal satisfaction during the first month postpartum: A comparison of Japanese mothers by age and parity. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 23, e12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prabhakar, A.S.; Guerra-Reyes, L.; Effron, A.; Kleinschmidt, V.M.; Driscoll, M.; Peters, C.; Pereira, V.; Alshehri, M.; Ongwere, T.; Siek, K.A. “Let me know if you need anything”: Support realities of new mothers. In Proceedings of the 11th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, Barcelona, Spain, 2 May 2017; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, S.; Page, A.E.; Emmott, E.H. The differential role of practical and emotional support in infant feeding experience in the UK. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börjesson, B.; Paperin, C.; Lindell, M. Maternal support during the first year of infancy. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (months) | 7.25 (3.11) | 1–12 | ||

| Mother age (years) | 32.80 (4.07) | 21–42 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| High school or below | 14 | 6.8 | ||

| College | 17 | 8.3 | ||

| University | 127 | 62.0 | ||

| Graduate | 47 | 22.9 | ||

| Working status | ||||

| Yes | 100 | 48.8 | ||

| No (including maternal leave) | 105 | 51.2 |

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Spouses Mean (SD) | Maternal Relatives Mean (SD) | In-Laws Mean (SD) | Friends Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting stress | |||||

| Parental distress | 29.53 (7.97) | ||||

| Parent–child dysfunctional interaction | 21.49 (6.71) | ||||

| Difficult child | 27.22 (8.65) | ||||

| Total | 78.19 (19.86) | ||||

| Maternal confidence | 49.74 (5.55) | ||||

| Social support | |||||

| Emotional | 49.90 (8.59) | 13.37 (2.91) | 13.42 (2.71) | 10.05 (3.71) | 13.06 (2.67) |

| Informational | 45.58 (9.24) | 10.47 (3.44) | 12.55 (2.97) | 10.59 (3.37) | 11.99 (3.26) |

| Appraisal | 50.37 (9.07) | 13.34 (2.93) | 13.18 (2.78) | 10.82 (3.53) | 13.02 (2.59) |

| Instrumental | 48.65 (8.83) | 13.94 (2.53) | 13.27 (2.91) | 10.56 (3.72) | 10.89 (3.16) |

| Total | 194.51 (31.64) | 51.11 (10.15) | 52.42 (9.76) | 42.03 (12.86) | 48.96 (10.02) |

| Variables | Total SS | Spouses | Maternal Relatives | In-Laws | Friends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting stress vs. | |||||

| Emotional support | −0.357 | −0.276 | −0.275 | −0.216 | −0.265 |

| Informational support | −0.202 | −0.169 | −0.144 | −0.106 a | −0.119 a |

| Appraisal support | −0.330 | −0.250 | −0.263 | −0.208 | −0.291 |

| Instrumental support | −0.330 | −0.245 | −0.254 | −0.190 | −0.220 |

| Total | −0.350 | −0.262 | −0.257 | −0.210 | −0.253 |

| Maternal confidence vs. | |||||

| Emotional support | 0.249 | 0.245 | 0.197 | 0.155 | 0.186 |

| Informational support | 0.216 | 0.186 | 0.165 | 0.115 a | 0.136 a |

| Appraisal support | 0.312 | 0.278 | 0.332 | 0.171 | 0.238 |

| Instrumental support | 0.279 | 0.170 | 0.219 | 0.186 | 0.242 |

| Total | 0.301 | 0.248 | 0.258 | 0.180 | 0.232 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.-H.; Lee, T.-Y.; Lin, X.-T.; Duan, H.-Y. Maternal Confidence and Parenting Stress of First-Time Mothers in Taiwan: The Impact of Sources and Types of Social Support. Healthcare 2022, 10, 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050878

Huang H-H, Lee T-Y, Lin X-T, Duan H-Y. Maternal Confidence and Parenting Stress of First-Time Mothers in Taiwan: The Impact of Sources and Types of Social Support. Healthcare. 2022; 10(5):878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050878

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Hsin-Hui, Tzu-Ying Lee, Xin-Ting Lin, and Hui-Ying Duan. 2022. "Maternal Confidence and Parenting Stress of First-Time Mothers in Taiwan: The Impact of Sources and Types of Social Support" Healthcare 10, no. 5: 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050878

APA StyleHuang, H.-H., Lee, T.-Y., Lin, X.-T., & Duan, H.-Y. (2022). Maternal Confidence and Parenting Stress of First-Time Mothers in Taiwan: The Impact of Sources and Types of Social Support. Healthcare, 10(5), 878. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050878