Prescription of Silexan Is Associated with Less Frequent General Practitioner Repeat Consultations Due to Disturbed Sleep Compared to Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists: A Retrospective Database Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Database

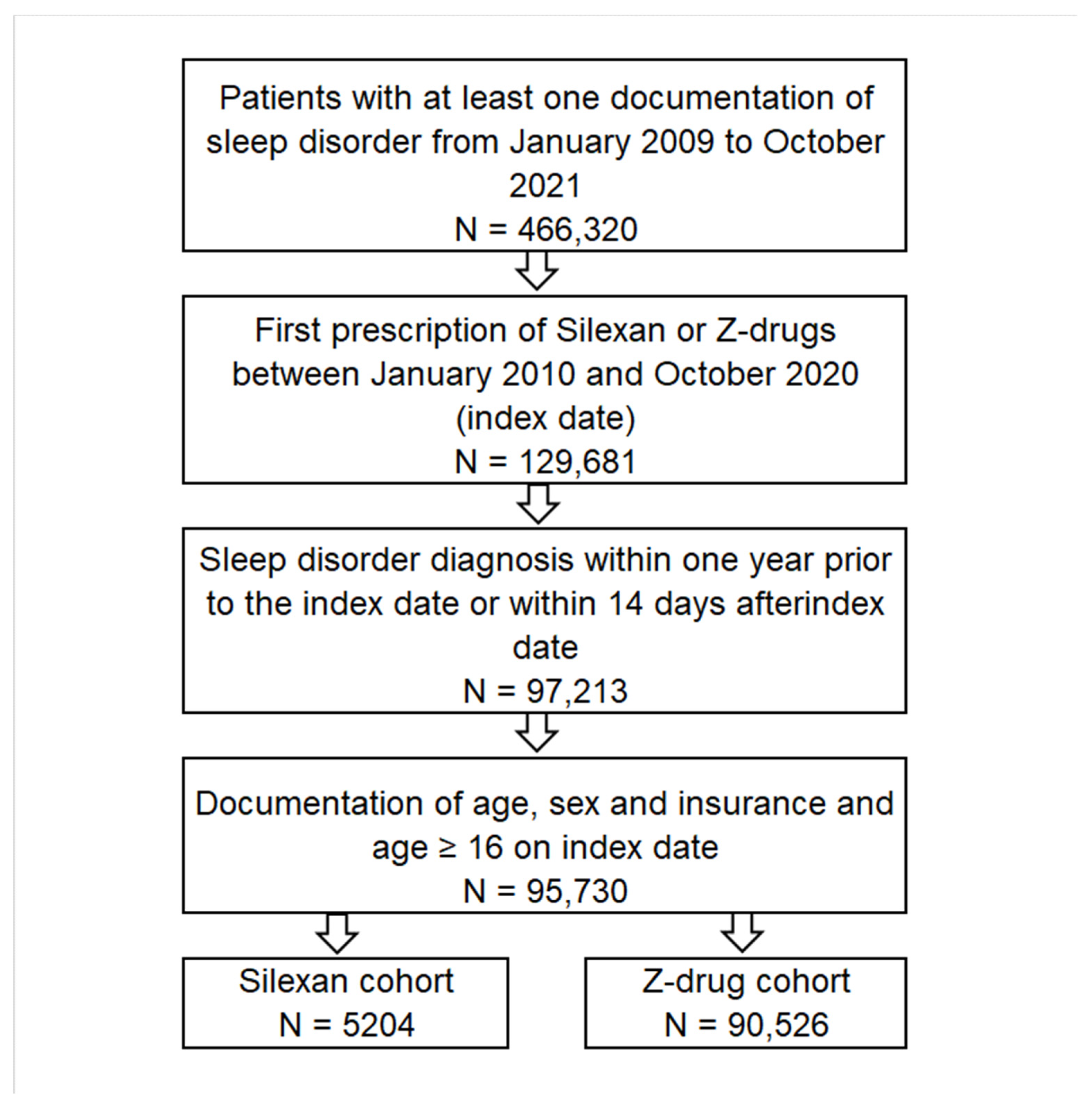

2.2. Study Population and Outcome

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Study Sample

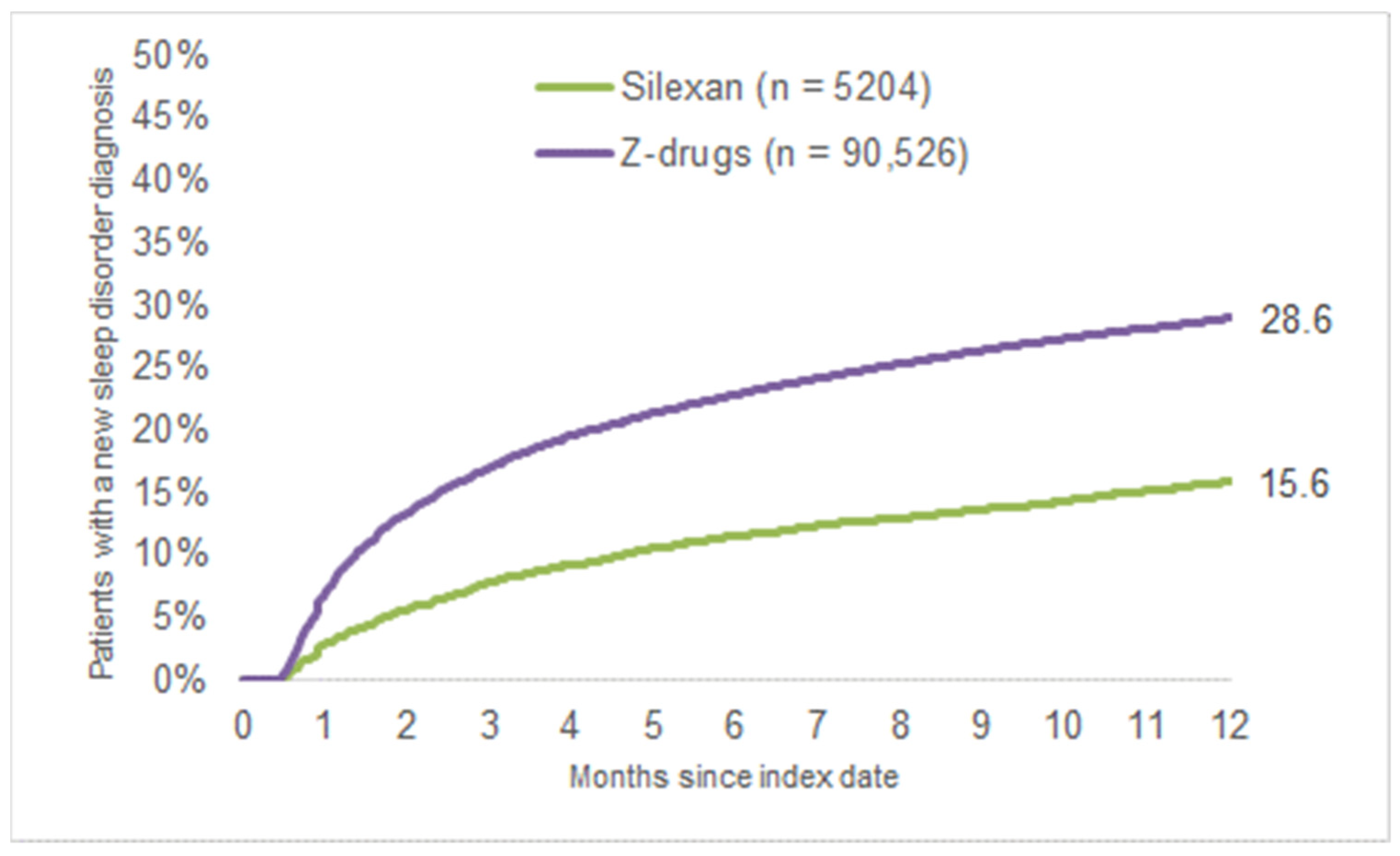

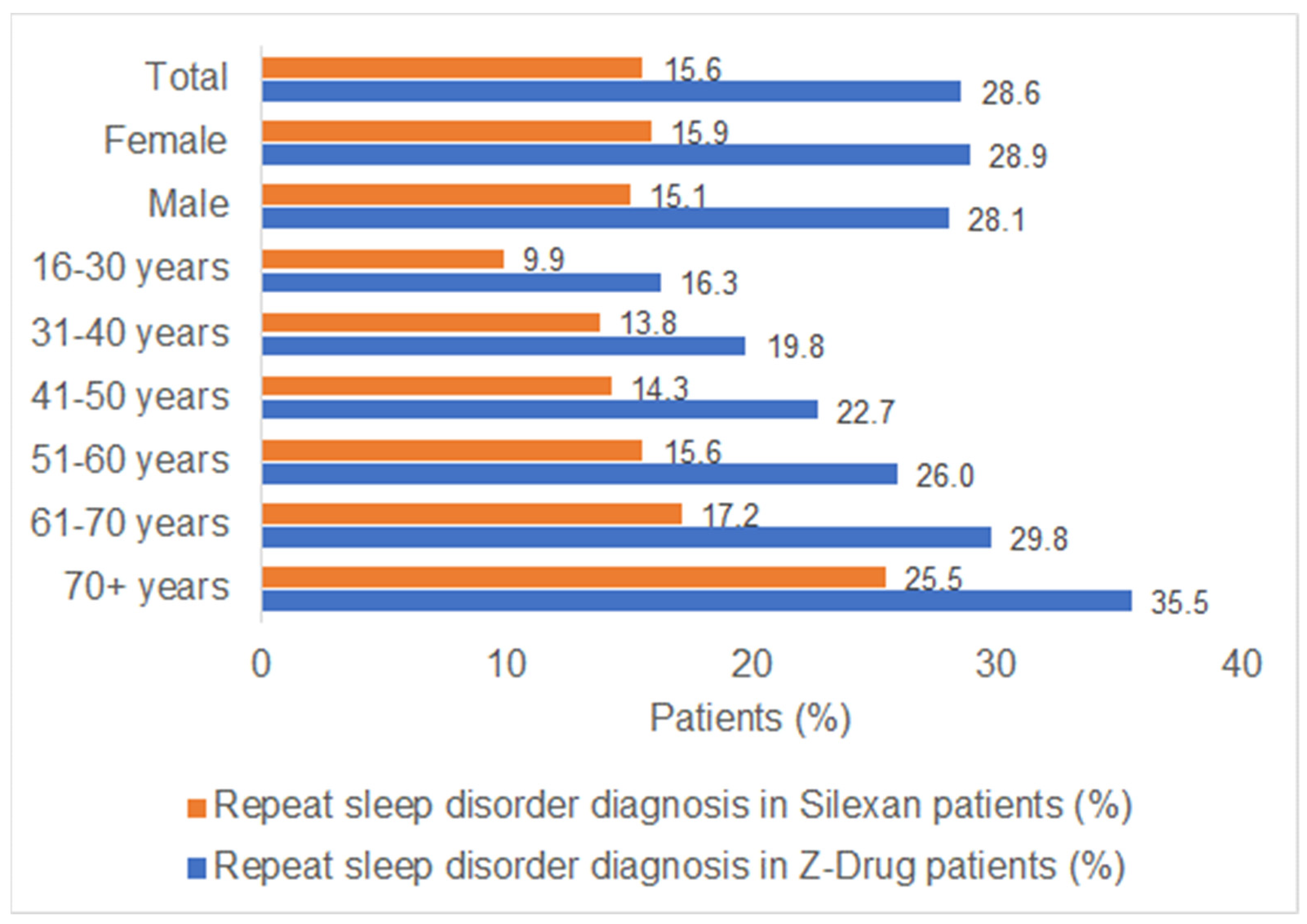

3.2. New Sleep Disorder Diagnoses

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Results

4.2. Interpretation of Results

4.3. Study Limitations

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karna, B.; Sankari, A.; Tatikonda, G. Sleep Disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rémi, J.; Pollmächer, T.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Trenkwalder, C.; Young, P. Sleep-Related Disorders in Neurology and Psychiatry. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorvatn, B.; Grønli, J.; Pallesen, S. Prevalence of different parasomnias in the general population. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hapke, U.; Maske, U.E.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Bode, L.; Schlack, R.; Busch, M.A. Chronic stress among adults in Germany: Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2013, 56, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, H.P.; Saliger, J.; Kasper, S.; Möller, H.J.; Seifritz, E. Subsyndromal generalised anxiety disorder: Operationalisation and epidemiology—A systematic literature survey. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2021, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, C.M.; Kim, H.Y.; Na, H.K.; Cho, K.H.; Chu, M.K. The Effect of Anxiety and Depression on Sleep Quality of Individuals With High Risk for Insomnia: A Population-Based Study. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aernout, E.; Benradia, I.; Hazo, J.B.; Sy, A.; Askevis-Leherpeux, F.; Sebbane, D.; Roelandt, J.L. International study of the prevalence and factors associated with insomnia in the general population. Sleep Med. 2021, 82, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Baum, E.; Cohrs, S.; Crönlein, T.; Hajak, G.; Hertenstein, E.; Klose, P.; Langhorst, J.; Mayer, G.; Nissen, C.; et al. S3-Leitlinie Nicht erholsamer Schlaf/Schlafstörungen. Somnologie 2017, 21, 2–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, G.; Liao, V.W.Y.; Ahring, P.K.; Chebib, M. The Z-Drugs Zolpidem, Zaleplon, and Eszopiclone Have Varying Actions on Human GABA A Receptors Containing γ1, γ2, and γ3 Subunits. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 599812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchette, D.; Akhondi, H.; Quick, J. Zolpidem. [Updated 1 October 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442008/ (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Khan, H.; Garg, A.; Agarwal, N.B.; Yadav, D.K.; Khan, M.A.; Hussain, S. Zolpidem use and risk of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 316, 114777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishtala, P.S.; Chyou, T.Y. Zopiclone Use and Risk of Fractures in Older People: Population-Based Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 368.e1–368.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbourt, K.; Nevo, O.N.; Zhang, R.; Chan, V.; Croteau, D. Association of eszopiclone, zaleplon, or zolpidem with complex sleep behaviors resulting in serious injuries, including death. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2020, 29, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bent, S.; Padula, A.; Moore, D.; Patterson, M.; Mehling, W. Valerian for sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-San-Martín, M.I.; Masa-Font, R.; Palacios-Soler, L.; Sancho-Gómez, P.; Calbó-Caldentey, C.; Flores-Mateo, G. Effectiveness of Valerian on insomnia: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.J.; Page, A.T. Herbal medicine for insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, H.J.; Volz, H.P.; Dienel, A.; Schläfke, S.; Kasper, S. Efficacy of Silexan in subthreshold anxiety: Meta-analysis of randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 269, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, W.S.; Dolzhenko, A.V.; Jalal, Z.; Hadi, M.A.; Khan, T.M. Efficacy and safety of lavender essential oil (Silexan) capsules among patients suffering from anxiety disorders: A network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, S.; Müller, W.E.; Volz, H.P.; Möller, H.J.; Koch, E.; Dienel, A. Silexan in anxiety disorders: Clinical data and pharmacological background. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 19, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifritz, E.; Schläfke, S.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Beneficial effects of Silexan on sleep are mediated by its anxiolytic effect. J. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 115, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathmann, W.; Bongaerts, B.; Carius, H.J.; Kruppert, S.; Kostev, K. Basic characteristics and representativeness of the German Disease Analyzer database. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 56, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartova, L.; Dold, M.; Volz, H.P.; Seifritz, E.; Möller, H.J.; Kasper, S. Beneficial effects of Silexan on co-occurring depressive symptoms in patients with subthreshold anxiety and anxiety disorders: Randomized, placebo-controlled trials revisited. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Känel, R.; Kasper, S.; Bondolfi, G.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Hättenschwiler, J.; Hatzinger, M.; Imboden, C.; Heitlinger, E.; Seifritz, E. Therapeutic effects of Silexan on somatic symptoms and physical health in patients with anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e01997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, L.S.; Otuyama, L.J.; Fumo-Dos-Santos, C.; Tufik, S.; Poyares, D. Sublingual and oral zolpidem for insomnia disorder: A 3-month randomized trial. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.K.; Roth, T.; Randazzo, A.; Erman, M.; Jamieson, A.; Scharf, M.; Schweitzer, P.K.; Ware, K. Eight Weeks of Non-Nightly Use of Zolpidem for Primary Insomnia. Sleep 2000, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermani, M.; Marcus, M.; Katzman, M.A. Rates of detection of mood and anxiety disorders in primary care: A descriptive, cross-sectional study. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011, 13, PCC.10m01013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Patients with Silexan Prescription | Patients with Z-Drug Prescription | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5204 | 90,526 | |

| Age mean (SD) | 48.7 (19.2) | 61.5 (18.2) | <0.001 |

| 16–30 years [n (%)] | 1172 (22.5%) | 5948 (6.6%) | <0.001 |

| 31–40 years [n (%)] | 680 (13.1%) | 7255 (8.0%) | <0.001 |

| 41–50 years [n (%)] | 938 (18.0%) | 12,090 (13.4%) | <0.001 |

| 51–60 years [n (%)] | 982 (18.9%) | 16,669 (18.4%) | 0.409 |

| 61–70 years [n (%)] | 594 (11.4%) | 14,668 (16.2%) | <0.001 |

| >70 years [n (%)] | 838 (16.1%) | 33,896 (37.4%) | <0.001 |

| Sex: female [n (%)] | 3456 (66.4%) | 53,982 (59.6%) | <0.001 |

| Private health insurance [n (%)] | 622 (12.0%) | 9020 (10.0%) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1128 (21.7%) | 16,665 (18.4%) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 586 (11,3%) | 4945 (5.5%) | <0.001 |

| Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorder | 685 (13.2%) | 7226 (8.0%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 345 (6.6%) | 12,233 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Back pain | 1216 (23.4%) | 20,396 (22.5%) | 0.161 |

| Osteoarthritis | 392 (7.5%) | 9939 (11.0%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchitis/COPD | 210 (4.0%) | 6679 (7.4%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 167 (3.2%) | 7864 (8.7%) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) * | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Silexan versus Z-Drugs | 0.56 (0.51–0.60) | <0.001 |

| Male vs. female | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.659 |

| Age: 18–30 years | Reference | |

| Age: 31–40 years | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) | <0.001 |

| Age: 41–50 years | 1.43 (1.32–1.54) | <0.001 |

| Age: 51–60 years | 1.64 (1.52–1.76) | <0.001 |

| Age: 61–70 years | 1.93 (1.79–2.08) | <0.001 |

| Age: 70+ years | 2.49 (2.32–2.68) | <0.001 |

| Private health insurance vs. statutory insurance | 1.23 (1.17–1.29) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1.35 (1.30–1.40) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.19 (1.12–1.26) | <0.001 |

| Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorder | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.030 |

| Diabetes | 1.33 (1.28–1.39) | <0.001 |

| Back pain | 1.14 (1.10–1.18) | <0.001 |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) | <0.001 |

| Chronic bronchitis/COPD | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) | <0.001 |

| Age Stratification | Odds Ratio (95% CI) * | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age: 16–30 years | 0.56 (0.46–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Age: 31–40 years | 0.65 (0.52–0.82) | <0.001 |

| Age: 41–50 years | 0.57 (0.47–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Age: 51–60 years | 0.53 (0.44–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Age: 61–70 years | 0.48 (0.38–0.59) | <0.001 |

| Age: 70+ years | 0.58 (0.50–0.68) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krüger, T.; Becker, E.-M.; Kostev, K. Prescription of Silexan Is Associated with Less Frequent General Practitioner Repeat Consultations Due to Disturbed Sleep Compared to Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists: A Retrospective Database Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010077

Krüger T, Becker E-M, Kostev K. Prescription of Silexan Is Associated with Less Frequent General Practitioner Repeat Consultations Due to Disturbed Sleep Compared to Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists: A Retrospective Database Analysis. Healthcare. 2023; 11(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrüger, Tillmann, Eva-Maria Becker, and Karel Kostev. 2023. "Prescription of Silexan Is Associated with Less Frequent General Practitioner Repeat Consultations Due to Disturbed Sleep Compared to Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists: A Retrospective Database Analysis" Healthcare 11, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010077

APA StyleKrüger, T., Becker, E.-M., & Kostev, K. (2023). Prescription of Silexan Is Associated with Less Frequent General Practitioner Repeat Consultations Due to Disturbed Sleep Compared to Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists: A Retrospective Database Analysis. Healthcare, 11(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010077