Identifying Coping Strategies Used by Transgender Individuals in Response to Stressors during and after Gender-Affirming Treatments—An Explorative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setup

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

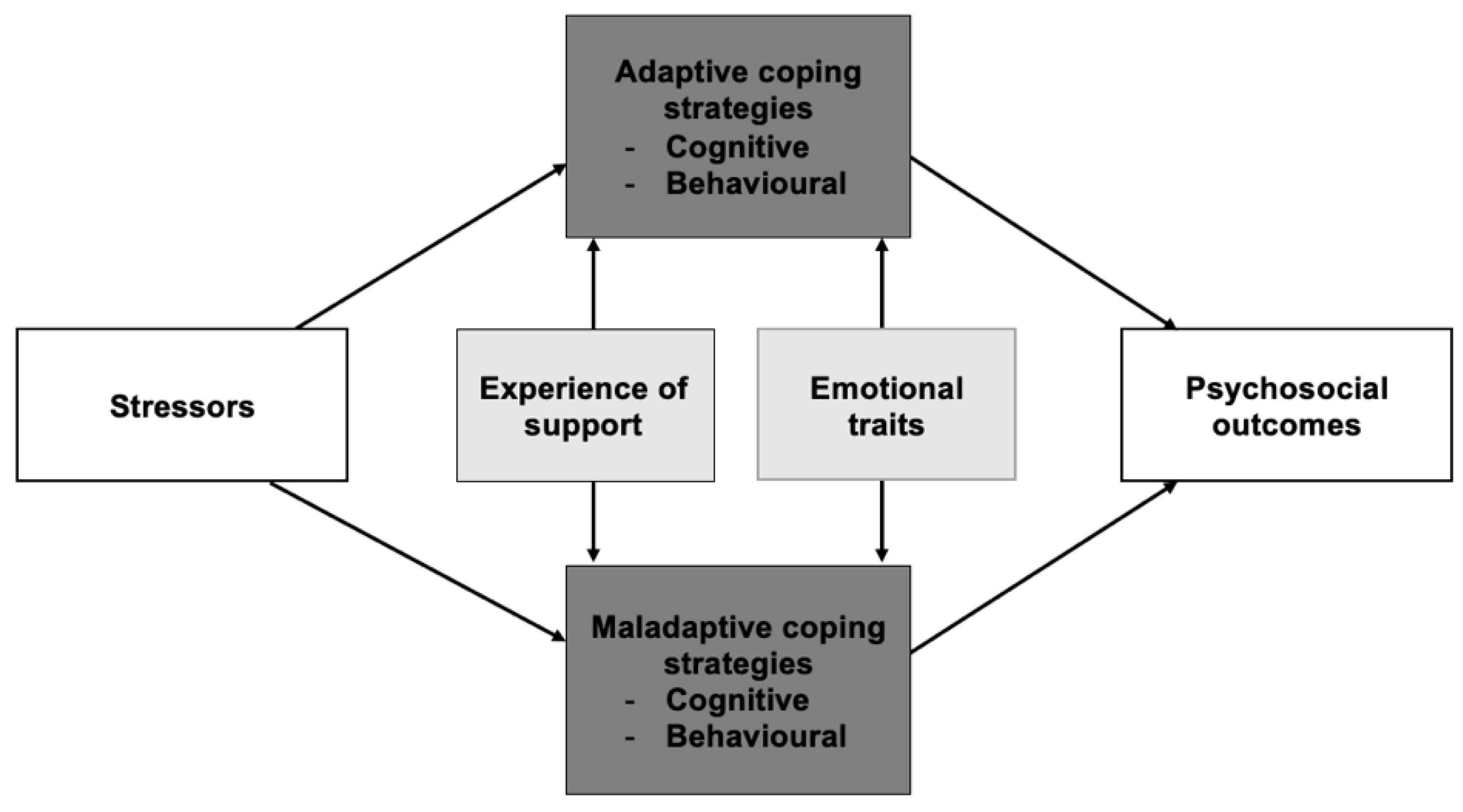

3.2. General Overview

3.3. Stressors

3.4. Moderating Factors

“I went all-in with the transition and accepted everything: the ups and the downs. I just know that, even during the darkest times, you will always climb up again to see the light. Hard times will make you stronger.”—Participant 01, male, age 52.

3.5. Adaptive Coping Strategies

“Emotionally, I am very stable now. I think that is because I accepted my male sides as well as my female sides.”—Participant 08, female, age 56.

“My dad still asks me why I want to be a girl. But I get it, he is 87 and has called me by my former name my entire life. I get why he still calls me that, it does not bother me. He just doesn’t really get it, that some men want to be women, you know.”—Participant 09, transgender, age 58.

“It was a relief to realize that I am not alone. I’m not insane, I’m not a freak. It is good to know that there are others like me.”—Participant 10, female, age 21.

“I made a tight band with a sock so I could bind the penis tightly to the back. When you wear pants, you cannot see a bump. I felt more like myself.”—Participant 11, female, age 28.

“My partner and I discussed it beforehand, so there would be no unpleasant surprises. We talked about what she would like and what I would like and what we could do to make it pleasant for both of us. We talked about it for a long time until we both felt good about it.”—Participant 12, male/transgender male, age 18.

3.6. Maladaptive Coping Strategies

“I can hardly look at myself in the mirror. When I’m naked, my confidence is almost zero.”—Participant 12, male/transgender male, age 18.

“I was not very happy with the results, that was difficult. The form and outline of my face was too feminine. I still had boob tissue, and the skin was loose. So, I went back to have another operation to make it look more masculine.”—Participant 07, male/transgender male, age 27.

“I feel very negatively towards being transgender. I am always afraid that other people notice it and talk about me. If I could make one wish, I would wish that I was not transgender. Then I wouldn’t have all the problems in my life, and I would be able to live normally.”—Participant 11, female, age 28.

“I am always aware of other people’s reaction to me. How they look at me and what they think of me. […] The other day, I heard someone ask: is that a man or a woman? That bothered me a lot. Immediately, I wondered what I had done to be viewed masculine. Did I walk too fast or look irritated or behave odd?”—Participant 03, female, age 52.

“Sometimes I think that I’m not the problem, the rest of the world is. They are all confused because I am confused about my gender. But who is really the problem? Not me!”—Participant 13, male, age 40.

“Isolation is the real problem when you grow up with gender incongruence. You can never live up to the expectations, so you always feel like you must hide a part of yourself. You feel like you are alone in the world. I still isolate myself when I feel bad.”—Participant 14, male/transgender male, age 62.

“Transgender individuals do not often ask for help. We are just used to doing everything alone, that’s a hard habit to break. I always tried to solve everything by myself.”—Participant 14, male/transgender male, age 62.

“I was stoned for a very long time, almost 20 years. I tried to dull a lot of pain and suffering by smoking weed.”—Participant 13, male, age 40.

4. Discussion

4.1. Most-Reported Coping Strategies

4.2. Moderating Factors

4.3. General and Transgender Specific Coping Strategies

4.4. Possible Approaches for Intervention

4.5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association; American Psychiatric Association DSMTF (Eds.) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E.; Bockting, W.; Botzer, M.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.; DeCuypere, G.; Feldman, J.; Fraser, L.; Green, J.; Knudson, G.; Meyer, W.J.; et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int. J. Transgenderism 2012, 13, 165–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira Passos, T.; Teixeira, M.; Almeida-Santos, M. Quality of Life After Gender Affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2020, 17, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhejne, C.; Van Vlerken, R.; Heylens, G.; Arcelus, J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heylens, G.; Elaut, E.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Paap, M.C.S.; Cerwenka, S.; Richter-Appelt, H.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Haraldsen, I.R.; De Cuypere, G. Psychiatric characteristics in transsexual individuals: Multicentre study in four European countries. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Blok, C.J.; Wiepjes, C.M.; van Velzen, D.M.; Staphorsius, A.S.; Nota, N.M.; Gooren, L.J.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; den Heijer, M. Mortality trends over five decades in adult transgender people receiving hormone treatment: A report from the Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.; Craig, S.L.; D’souza, S.; McInroy, L.B. Suicidality among Transgender Youth: Elucidating the Role of Interpersonal Risk Factors. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP2696–NP2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, N.M.; Steensma, T.D.; Carmichael, P.; VanderLaan, D.P.; Aitken, M.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; de Vries, A.L.C.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Wasserman, L.; et al. Suicidality in clinic-referred transgender adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Grift, T.C.; Elaut, E.; Cerwenka, S.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; De Cuypere, G.; Richter-Appelt, H.; Kreukels, B.P.C. Effects of Medical Interventions on Gender Dysphoria and Body Image: A Follow-Up Study. Psychosom. Med. 2017, 79, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bränström, R.; Pachankis, J.E. Reduction in Mental Health Treatment Utilization Among Transgender Individuals After Gender-Affirming Surgeries: A Total Population Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Grift, T.C.; Elfering, L.; Greijdanus, M.; Smit, J.M.; Bouman, M.B.; Klassen, A.F.; Mullender, M.G. Subcutaneous Mastectomy Improves Satisfaction with Body and Psychosocial Function in Trans Men: Findings of a Cross-Sectional Study Using the BODY-Q Chest Module. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 142, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Grift, T.C.; Elaut, E.; Cerwenka, S.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Kreukels, B.P.C. Surgical Satisfaction, Quality of Life, and Their Association After Gender-Affirming Surgery: A Follow-up Study. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2018, 44, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dhejne, C.; Lichtenstein, P.; Boman, M.; Johansson, A.; Långström, N.; Landén, M. Long-Term Follow-Up of Transsexual Persons Undergoing Sex Reassignment Surgery: Cohort Study in Sweden. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Brouwer, I.J.; Elaut, E.; Becker-Hebly, I.; Heylens, G.; Nieder, T.O.; van de Grift, T.C.; Kreukels, B.P.C. Aftercare Needs Following Gender-Affirming Surgeries: Findings From the ENIGI Multicenter European Follow-Up Study. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, M.; Cogliandro, A.; Di Stefano, N.; Tambone, V.; Persichetti, P. A Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Following Transsexual Surgery. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 41, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiepjes, C.M.; den Heijer, M.; Bremmer, M.; Nota, N.M.; de Blok, C.J.; Coumou, B.J.; Steensma, T.D. Trends in suicide death risk in transgender people: Results from the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria study (1972–2017). Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 141, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Pub. Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 857–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Testa, R.J.; Habarth, J.; Peta, J.; Balsam, K.; Bockting, W. Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenBos, G.R. (Ed.) APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 15, pp. 1204–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen, C. Stress and depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dohrenwend, B.P. The Role of Adversity and Stress in Psychopathology: Some Evidence and Its Implications for Theory and Research. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2000, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A. Psychological coping, individual differences and physiological stress responses. In Personality and Stress: Individual Differences in the Stress Process; Wiley Series on Studies in Occupational Stress; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner, M.; Endler, N.S. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Contrada, R.J. The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Edited by Susan Folkman. Oxford University Press, New York, 2011. No. of pages: 469. Price: $125.00 (US), £80.00 (UK). ISBN 978-0-19-537534-3. Psycho Oncol. 2011, 20, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, S.L.; Katz-Wise, S.L.; Tebbe, E.N.; Howard, K.A.S.; Schneider, C.L.; Rodriguez, A. Transgender Emotional and Coping Processes: Facilitative and Avoidant Coping Throughout Gender Transitioning. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 41, 601–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A.F.; Kaur, M.; Johnson, N.; Kreukels, B.P.; McEvenue, G.; Morrison, S.D.; Mullender, M.G.; Poulsen, L.; Ozer, M.; Rowe, W.; et al. International phase I study protocol to develop a patient-reported outcome measure for adolescents and adults receiving gender-affirming treatments (the GENDER-Q). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e025435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomini, M.K.; Cook, D.J.; Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? JAMA 2000, 284, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Karademas, E.C.; Hondronikola, I. The impact of illness acceptance and helplessness to subjective health, and their stability over time: A prospective study in a sample of cardiac patients. Psychol. Health Med. 2010, 15, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Bursnall, S. Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes for children of a parent with multiple sclerosis and comparisons with children of healthy parents. Clin. Rehabil. 2006, 20, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilski, M.; Gabryelski, J.; Brola, W.; Tomasz, T. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Links to acceptance, coping strategies and disease severity. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, N.; D’Ambrosio, C.; Tang, K.K.; Rao, P. Estimating the Mental Health Effects of Social Isolation. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.E.; Dugan, E. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Health Among Older Adults. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbach, J.T.; Gibbs, J.J. A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.F.; Waldo, C.R.; Rothblum, E.D. A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2001, 71, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stanton, A.L.; Danoff-Burg, S.; Cameron, C.L.; Bishop, M.; Collins, C.A.; Kirk, S.B.; Sworowski, L.A.; Twillman, R. Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widiger, T.A.; Oltmanns, J. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1985; pp. 310–357. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M.S.; Koeske, G.F.; Silvestre, A.J.; Korr, W.S.; Sites, E.W. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.R.; Perry, B.L. Sexual Identity Distress, Social Support, and the Health of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youth. J. Homosex. 2006, 51, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacsa-Domocmat, M.C. Spirituality and Chronic Illness: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2014, 3, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar]

- Khalili, N.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Mokarian, F.; Bahrami, F. Coping strategies, quality of life and pain in women with breast cancer. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2013, 18, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Juster, R.-P.; Ouellet, E.; Lefebvre-Louis, J.-P.; Sindi, S.; Johnson, P.J.; Smith, N.G.; Lupien, S.J. Retrospective coping strategies during sexual identity formation and current biopsychosocial stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaysen, D.L.; Kulesza, M.; Balsam, K.F.; Rhew, I.C.; Blayney, J.A.; Lehavot, K.; Hughes, T.L. Coping as a mediator of internalized homophobia and psychological distress among young adult sexual minority women. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2014, 1, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia, J.; Vargas, N.; Clark, J.L.; Magaña Álvarez, M.; Nelons, D.A.; Parker, R.G. Social isolation and connectedness as determinants of well-being: Global evidence mapping focused on LGBTQ youth. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, S.L.; Belcourt, S.; Conniff, J.; Parks, R.; Pantalone, D.W.; Katz-Wise, S.L. A Grounded Theory Study of the Development of Trans Youths’ Awareness of Coping with Gender Identity. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3048–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariola, E.; Lyons, A.; Leonard, W.; Pitts, M.; Badcock, P.; Couch, M. Demographic and Psychosocial Factors Associated With Psychological Distress and Resilience Among Transgender Individuals. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockting, W.O.; Miner, M.H.; Swinburne Romine, R.E.; Hamilton, A.; Coleman, E. Stigma, Mental Health, and Resilience in an Online Sample of the US Transgender Population. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttbrock, L.; Hwahng, S.; Bockting, W.; Rosenblum, A.; Mason, M.; Macri, M.; Becker, J. Psychiatric Impact of Gender-Related Abuse Across the Life Course of Male-to-Female Transgender Persons. J. Sex Res. 2010, 47, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W.O.; Miner, M.H.; Swinburne Romine, R.E.; Dolezal, C.; Robinson, B.E.; Rosser, B.S.; Coleman, E. The Transgender Identity Survey: A Measure of Internalized Transphobia. LGBT Health 2020, 7, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Molina, K.M.; James, D. Discrimination, internalized racism, and depression: A comparative study of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willis, H.A.; Sosoo, E.E.; Bernard, D.L.; Neal, A.; Neblett, E.W. The Associations Between Internalized Racism, Racial Identity, and Psychological Distress. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadj-Moussa, M.; Ohl, D.A.; Kuzon, W.M., Jr. Feminizing Genital Gender-Confirmation Surgery. Sex. Med. Rev. 2018, 6, 457–468.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardein, J.N.; Zhao, L.; Nikolavsky, D. Management of Vaginoplasty and Phalloplasty Complications. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 46, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allvin, R.; Ehnfors, M.; Rawal, N.; Idvall, E. Experiences of the Postoperative Recovery Process: An Interview Study. Open Nurs. J. 2008, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Austin, A.; Craig, S.L. Empirically Supported Interventions for Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. J. Evid. Inf. Soc. Work 2015, 12, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.L.; Austin, A.; Huang, Y.-T. Being humorous and seeking diversion: Promoting healthy coping skills among LGBTQ+ youth. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 22, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.L.; Leung, V.W.Y.; Pascoe, R.; Pang, N.; Iacono, G.; Austin, A.; Dillon, F. AFFIRM Online: Utilising an Affirmative Cognitive-Behavioural Digital Intervention to Improve Mental Health, Access, and Engagement among LGBTQA+ Youth and Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhardt, M.; Dolbier, C. Evaluation of a Resilience Intervention to Enhance Coping Strategies and Protective Factors and Decrease Symptomatology. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C. Conceptualization and Measurement of Coping During Adolescence: A Review of the Literature. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2010, 42, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Age | Gender Identity | Sex Assigned at Birth | Gender-Affirming Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 52 | Male | Female | HRT |

| 2 | 26 | Male/Transgender male | Female | HRT, mastectomy |

| 3 | 52 | Female | Male | HRT, vaginoplasty, chondrolaryngoplasty |

| 4 | 41 | Male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, colpectomy, metoidioplasty |

| 5 | 60 | Male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty with urethral lengthening, phalloplasty with urethral lengthening, erectile prosthetic, testicle implants |

| 6 | 23 | Female | Male | HRT, puberty inhibitors |

| 7 | 27 | Male/Transgender male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, colpectomy |

| 8 | 56 | Female | Male | HRT, vaginoplasty |

| 9 | 58 | Transgender | Male | HRT |

| 10 | 21 | Female | Male | HRT, puberty inhibitors, orchidectomy |

| 11 | 28 | Female | Male | HRT |

| 12 | 18 | Male/Transgender male | Female | HRT |

| 13 | 40 | Male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy |

| 14 | 62 | Male/Transgender male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, metoidioplasty |

| 15 | 26 | Male/Transgender male | Female | HRT, mastectomy |

| 16 | 27 | Male | Female | HRT, mastectomy |

| 17 | 22 | Male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy |

| 18 | 61 | Female | Male | HRT, breast augmentation, FFS, chondrolaryngoplasty, vaginoplasty, glottoplasty |

| 19 | 37 | Male | Female | HRT, mastectomy, hysterectomy, colpectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Stressors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Theme | Minor Theme | N= | Quote (Participant Number) |

| Lack of support system | Lack of acceptance or support from family or friends | 47 | When we were at the zoo, I told my mom that I would like her to call me [new name], but she shouted at me: I will never ever accept you! (01) |

| Transition related | Not being informed enough during medical transition | 62 | I was carrying this weight with me until I finally spoke with the surgeon. I thought: why didn’t you tell me this EARLIER? I would have been just fine knowing, but I would have liked to know. (02) |

| Dissatisfaction with healthcare providers during medical transition | 48 | I often feel like the doctor does not listen to me, that is very disappointing. (03) | |

| Missing guidance with social transition | 31 | I would advise to focus more on guidance when you start the transition. What does it mean? How do you present yourself? How do you handle people’s reactions when they don’t know how to address you? I would have liked that kind of guidance. When am I going to do the social transition? How am I going to approach that? (04) | |

| Revision surgery | 11 | When I got the protheses, it did not fit properly. I had to return to the hospital several times. In total, I had to undergo 14–15 operations to fix the problem. (05) | |

| Post-transition: physical | Complications | 33 | My labia minora were turning black at some point because they were dying. (03) |

| Diminished sexual pleasure | 13 | Not good, my libido has decreased enormously since I started the hormonal replacement therapy. (06) | |

| Post-transition: psychosocial | Doubts about transition | 24 | Sometimes I feel a little schizophrenic or something. There’s a part of me, the biggest part, that feels like a man but there’s another part that’s not comfortable with it and it is a constant internal conflict. (07) |

| Had to get used to the physical and mental changes | 23 | Before the transition, I could easily carry heavy bags and stuff, but now I struggle to do so. My strength has decreased a lot. Last week, I wanted to carry a suitcase for a friend, but I realized that I could no longer do so. Somebody else had to carry it. (08) | |

| Transition does not solve all problems | 23 | I hoped or thought that transitioning would make me happy. At the very beginning you think: if I transition then I am happy, but it doesn’t turn out that way. It does help, but it is not going to be the sole reason for happiness. (07) | |

| Expectations were not met | 20 | Some things you don’t expect. And of course, everyone experiences that in their own way. Some results turned out differently than I expected, but that does not mean it went wrong, probably my expectations were wrong. (05) |

| Adaptive Coping Strategies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Theme | Minor Theme | Mini Theme | N= |

| Cognitive | Acceptance | 119 | |

| Adaptive cognitions concerning gender and transition | Not thinking binary | 32 | |

| Rationalizing | Self-knowledge | 51 | |

| Behavioural | Seeking help and guidance | Seeking help/support | 44 |

| Finding (spiritual) meaning | 21 | ||

| Autonomy in arranging transition | Taking small steps | 21 | |

| Non-medical interventions | 26 | ||

| Problem-solving | Confronting | 24 | |

| Maladaptive Coping Strategies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Theme | Minor Theme | Mini Theme | N= |

| Cognitive | Lack of self-acceptance | 36 | |

| Maladaptive cognitions concerning gender and transition | Stereotypical image of man/woman | 75 | |

| Focus on gender-incongruent characteristics | 66 | ||

| Internalized transphobia | 39 | ||

| External validation of self-esteem | Comparing to others | 53 | |

| Externalization | 21 | ||

| Behavioural | Isolation | Denial of identity | 87 |

| Hiding | 70 | ||

| Avoidance | Solving alone | 32 | |

| Dissociation | 33 | ||

| Self-destructive behaviour | Substance abuse | 19 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oorthuys, A.O.J.; Ross, M.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Mullender, M.G.; van de Grift, T.C. Identifying Coping Strategies Used by Transgender Individuals in Response to Stressors during and after Gender-Affirming Treatments—An Explorative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010089

Oorthuys AOJ, Ross M, Kreukels BPC, Mullender MG, van de Grift TC. Identifying Coping Strategies Used by Transgender Individuals in Response to Stressors during and after Gender-Affirming Treatments—An Explorative Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleOorthuys, Anna O. J., Maeghan Ross, Baudewijntje P. C. Kreukels, Margriet G. Mullender, and Tim C. van de Grift. 2023. "Identifying Coping Strategies Used by Transgender Individuals in Response to Stressors during and after Gender-Affirming Treatments—An Explorative Study" Healthcare 11, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010089

APA StyleOorthuys, A. O. J., Ross, M., Kreukels, B. P. C., Mullender, M. G., & van de Grift, T. C. (2023). Identifying Coping Strategies Used by Transgender Individuals in Response to Stressors during and after Gender-Affirming Treatments—An Explorative Study. Healthcare, 11(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010089