Prevalence and Determinants of Social Media Addiction among Medical Students in a Selected University in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Protocol

2.2. Participants, Sample Size, and Sampling

2.3. Study Tool and Measure

2.3.1. Sociodemographic and Behavioral Information

2.3.2. Assessment of Depressive Symptoms

2.3.3. Assessment of Anxiety Symptoms

2.3.4. Measurement of Social Media Addiction

2.4. Statistical Approach

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

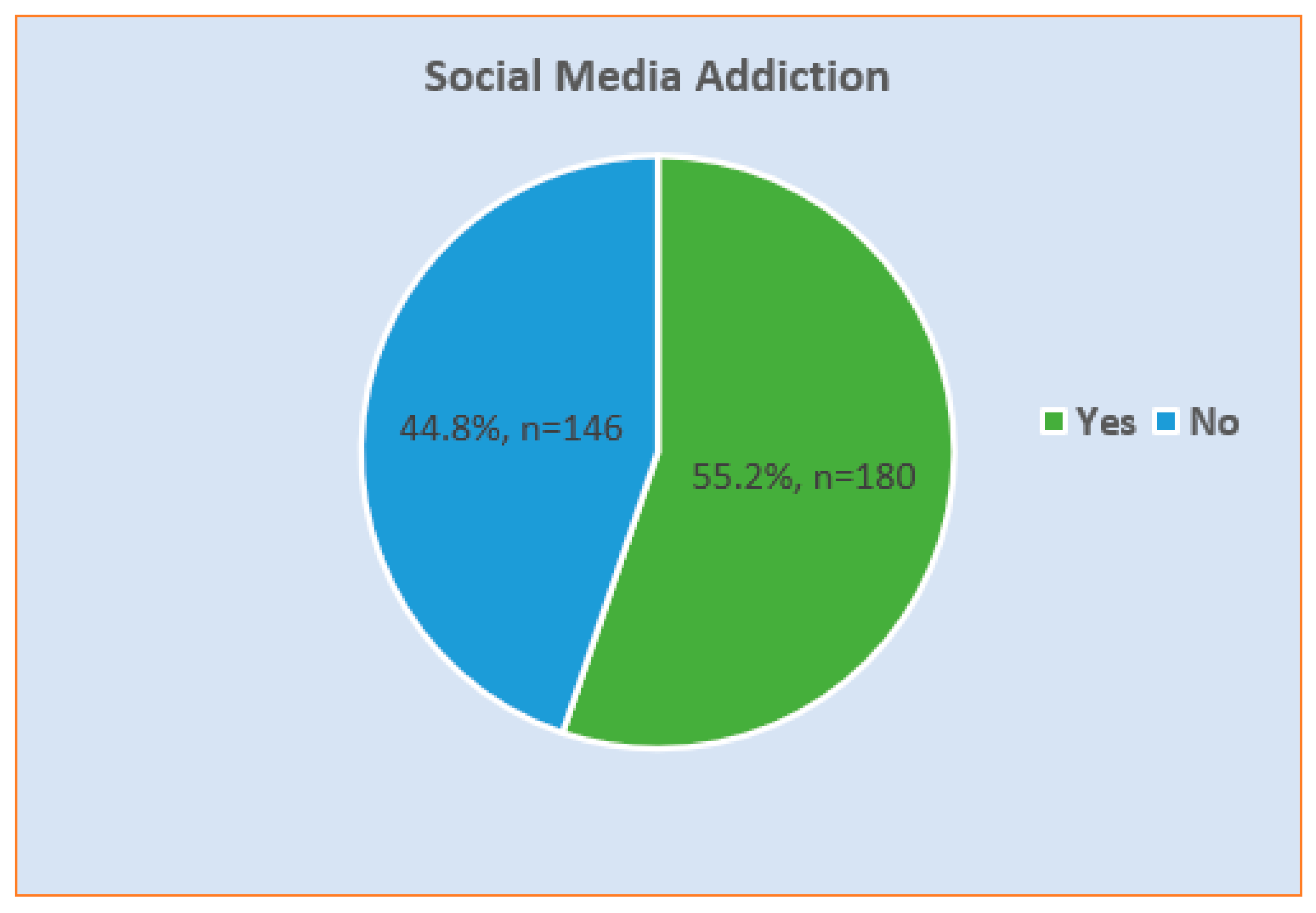

3.2. Social Media Addiction and Its Determinants

3.3. Social Media Apps-Related Information (Types and Frequently Used)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baccarella, C.V.; Wagner, T.F.; Kietzmann, J.H.; McCarthy, I.P. Social Media? It’s Serious! Understanding the Dark Side of Social Media. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Lau, Y.-C.; Luk, J.W. Social Capital—Accrual, Escape-from-Self, and Time-Displacement Effects of Internet Use during the COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Period: Prospective, Quantitative Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, H.; Sigerson, L.; Chau, C. Do the Socially Rich Get Richer? A Nuanced Perspective on Social Network Site Use and Online Social Capital Accrual. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, A.; Siddiqui, A.; Khalil, S.; Farag, S.; Alshahrani, N.; Alsabaani, A.; Korairi, H. WhatsApp-Based Intervention for Promoting Physical Activity among Female College Students, Saudi Arabia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2021, 27, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Starcevic, V. Problematic Social Networking Site Use: A Brief Review of Recent Research Methods and the Way Forward. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xiong, D.; Jiang, T.; Song, L.; Wang, Q. Social Media Addiction: Its Impact, Mediation, and Intervention. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cybersp. 2019, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Social Network Site Addiction—An Overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4053–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. The Associations between Problematic Social Networking Site Use and Sleep Quality, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Depression, Anxiety and Stress. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Foroughi, B.; Hyun, S.S. Drivers and Outcomes of Instagram Addiction: Psychological Well-Being as Moderator. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Sidani, J.E.; Shensa, A.; Radovic, A.; Miller, E.; Colditz, J.B.; Hoffman, B.L.; Giles, L.M.; Primack, B.A. Association between Social Media Use and Depression among US Young Adults. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Lau, Y.; Chan, L.; Luk, J.W. Prevalence of Social Media Addiction across 32 Nations: Meta-Analysis with Subgroup Analysis of Classification Schemes and Cultural Values. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Jia, T.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, X. Risk Factors Associated with Social Media Addiction: An Exploratory Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köse, Ö.B.; Doğan, A. The Relationship between Social Media Addiction and Self-Esteem among Turkish University Students. Addicta Turk. J. Addict 2019, 6, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Sujan, M.S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Mohona, R.A.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Kamruzzaman, S.; Toma, T.Y.; Sakib, M.N.; Pinky, K.N.; Islam, M.R. Problematic Smartphone and Social Media Use among Bangladeshi College and University Students amid COVID-19: The Role of Psychological Well-Being and Pandemic Related Factors. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 647386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saud, D.F.; Alhaddab, S.A.; Alhajri, S.M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Aljohar, S.A.; Mortada, E.M. The Association between Body Image, Body Mass Index and Social Media Addiction among Female Students at a Saudi Arabia Public University. Mal. J. Med. Health Sci. 2019, 15, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gmi Blogger Saudi Arabia Social Media Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/saudi-arabia-social-media-statistics/ (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Alsabaani, A.; Alshahrani, A.A.; Abukaftah, A.S.; Abdullah, S.F. Association between Over-Use of Social Media and Depression among Medical Students, King Khalid University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 70, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halboub, E.; Othathi, F.; Mutawwam, F.; Madkhali, S.; Somaili, D.; Alahmar, N. Effect of Social Networking on Academic Achievement of Dental Students, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.J.; McConnachie, A.; Ross, S.; Morrison, J.M. First Year Medical Student Stress and Coping in a Problem-based Learning Medical Curriculum. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; West, C.P.; Satele, D.; Boone, S.; Tan, L.; Sloan, J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Burnout among US Medical Students, Residents, and Early Career Physicians Relative to the General US Population. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleisa, M.A.; Abdullah, N.S.; Alqahtani, A.A.A.; Aleisa, J.A.J.; Algethami, M.R.; Alshahrani, N.Z. Association between Alexithymia and Depression among King Khalid University Medical Students: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal Cut-off Score for Diagnosing Depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A Meta-Analysis. Cmaj 2012, 184, E191–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.; Al Zaid, K.; Al Faris, E. Screening for Somatization and Depression in Saudi Arabia: A Validation Study of the PHQ in Primary Care. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2002, 32, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, F.; Alshahrani, N.Z.; Abu Sabah, A.; Zarbah, A.; Abu Sabah, S.; Mamun, M.A. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Mental Health Problems in S Audi General Population during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PsyCh J. 2022, 11, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaber, M.I. The Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression among Medical Students of Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.; Almalki, A.; Alabdan, F.; Haddad, B. Depression among Medical Students in Saudi Medical Colleges: A Cross-Sectional Study. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, ume 9, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.; Manzar, M.D.; Anwer, S.; Albougami, A.; Salahuddin, M. Psychometric Properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale among Saudi University Male Students. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The Relationship between Addictive Use of Social Media and Video Games and Symptoms of Psychiatric Disorders: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘Components’ Model of Addiction within a Biopsychosocial Framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbeck, J. Are You a Social Media Addict? Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/your-online-secrets/201709/are-you-social-media-addict (accessed on 30 April 2013).

- Alnjadat, R.; Hmaidi, M.M.; Samha, T.E.; Kilani, M.M.; Hasswan, A.M. Gender Variations in Social Media Usage and Academic Performance among the Students of University of Sharjah. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 14, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The Relationship between Addictive Use of Social Media, Narcissism, and Self-Esteem: Findings from a Large National Survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thelwall, M. Social Networks, Gender, and Friending: An Analysis of MySpace Member Profiles. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2008, 59, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Social Media Addiction and Its Impact on College Students’ Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Stress. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2023, 32, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar, A.M.; Pandey, A.K.; Nayak, R.; Pujary, K.; Kumar, A. Impact of Social Media on the Academic Performance of Undergraduate Medical Students. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2021, 77, S37–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doleck, T.; Lajoie, S. Social Networking and Academic Performance: A Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018, 23, 435–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Luqman, A.; Feng, Y.; Ali, A. Adverse Consequences of Excessive Social Networking Site Use on Academic Performance: Explaining Underlying Mechanism from Stress Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouis, S. Impact of Cognitive Absorption on Facebook on Students’ Achievement. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, H.; Patel, H.; Aslam, H.M.; Ansari, I.Q.; Khan, M.; Iqbal, N.; Rasheed, H.; Jabbar, Q.; Khan, S.R.; Khalid, B. Effect of Facebook on the Life of Medical University Students. Int. Arch. Med. 2013, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.Y.; Mo, H.Y.; Potenza, M.N.; Chan, M.N.M.; Lau, W.M.; Chui, T.K.; Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.-Y. Relationships between Severity of Internet Gaming Disorder, Severity of Problematic Social Media Use, Sleep Quality and Psychological Distress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Suwayri, S.M. The Impact of Social Media Volume and Addiction on Medical Student Sleep Quality and Academic Performance: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Imam J. Appl. Sci. 2016, 1, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Asiri, A.K.; Almetrek, M.A.; Alsamghan, A.S.; Mustafa, O.; Alshehri, S.F. Impact of Twitter and WhatsApp on Sleep Quality among Medical Students in King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia. Sleep Hypn. 2018, 20, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.Z.; Shuhaiber, A.H.; Al-amer, R.M.; Abuadas, M.H.; Aburoomi, R.J. Correlation between Psychological Factors, Academic Performance and Social Media Addiction: Model-Based Testing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwagait, E.; Shahzad, B.; Alim, S. Impact of Social Media Usage on Students Academic Performance in Saudi Arabia. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haand, R.; Shuwang, Z. The Relationship between Social Media Addiction and Depression: A Quantitative Study among University Students in Khost, Afghanistan. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media on Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D. The Association between Facebook Addiction and Depression: A Pilot Survey Study among Bangladeshi Students. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Hussain, S.; Munir, N. Social Networking and Depression among University Students. Pak. J. Med. Res. 2018, 57, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shensa, A.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Sidani, J.E.; Bowman, N.D.; Marshal, M.P.; Primack, B.A. Problematic Social Media Use and Depressive Symptoms among US Young Adults: A Nationally-Representative Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 182, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyaroğlu, A.K.; Ergin, E.; Tosun, A.S.; Erdem, Ö. A Cross-sectional Study of Social Media Addiction and Social and Emotional Loneliness in University Students in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 2263–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.S.; Koh, Y.Y.W. Online Social Networking Addiction among College Students in Singapore: Comorbidity with Behavioral Addiction and Affective Disorder. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017, 25, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffar, M.; Mahmood, S.; Saleem, M.; Zakaria, E. Facebook Addiction: Relation with Depression, Anxiety, Loneliness and Academic Performance of Pakistani Students. Sci. Int. 2015, 27, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German Students—A Longitudinal Approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, E.M.; Kern, M.L.; Rickard, N.S. Social Networking Sites, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2016, 3, e5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegmann, E.; Oberst, U.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M. Online-Specific Fear of Missing out and Internet-Use Expectancies Contribute to Symptoms of Internet-Communication Disorder. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WhatsApp. About WhatsApp. Available online: https://www.whatsapp.com/about/?l=en (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Kircaburun, K.; Alhabash, S.; Tosuntaş, Ş.B.; Griffiths, M.D. Uses and Gratifications of Problematic Social Media Use among University Students: A Simultaneous Examination of the Big Five of Personality Traits, Social Media Platforms, and Social Media Use Motives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, A.J.; Zinn, M.F.; Schoenmakers, T.M.; Van de Mheen, D. Treating Internet Addiction with Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: A Thematic Analysis of the Experiences of Therapists. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2012, 10, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.M.; Mullai, M. Modeling Social Media Addiction with Case Detection and Treatment. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable (s) | Category | Frequency n | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 195 | 59.8 |

| Female | 131 | 40.2 | |

| Age (in years) | 18–20 | 19 | 5.8 |

| 21–23 | 186 | 57.1 | |

| ≥24 | 121 | 37.1 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 311 | 95.4 |

| Married | 15 | 4.6 | |

| Monthly Family Income | <3000 SR | 14 | 4.3 |

| 3000 to 10,000 SR | 59 | 18.1 | |

| 10,001 to 20,000 SR | 258 | 48.5 | |

| >20,000 SAR | 95 | 29.1 | |

| Education Level | 2nd year | 13 | 4.0 |

| 3rd year | 49 | 15.0 | |

| 4th year | 81 | 24.8 | |

| 5th year | 73 | 22.4 | |

| 6th year | 64 | 19.6 | |

| Intern | 46 | 14.1 | |

| Grade Point Average (GPA) | <2.5 | 16 | 4.9 |

| 2.5–3.49 | 88 | 27.0 | |

| 3.5–4.5 | 140 | 42.9 | |

| >4.5 | 82 | 25.2 | |

| Residence | Private housing | 255 | 78.2 |

| Renting housing | 52 | 16.0 | |

| University compound | 19 | 5.8 | |

| Educational Level of Father | Illiterate | 10 | 3.1 |

| Primary level | 26 | 8.0 | |

| Intermediate level | 38 | 11.7 | |

| Secondary level | 56 | 17.2 | |

| University level | 196 | 60.1 | |

| Educational Level of Mother | Illiterate | 32 | 9.8 |

| Primary level | 31 | 9.5 | |

| Intermediate level | 35 | 10.7 | |

| Secondary level | 62 | 19.0 | |

| University level | 166 | 50.9 | |

| Living with | Parents | 254 | 77.9 |

| Alone | 46 | 14.1 | |

| Friends or relatives | 26 | 8.0 | |

| Current Smoking Status | Yes | 39 | 12.0 |

| No | 287 | 88.0 | |

| Self-reported BMI Status | Underweight | 27 | 8.3 |

| Normal weight | 147 | 45.1 | |

| Overweight | 85 | 26.1 | |

| Obesity | 87 | 20.6 | |

| Physical Activity Level | No activity | 131 | 40.2 |

| <3 times per week | 108 | 33.1 | |

| 3 to 5 times per week | 62 | 19.0 | |

| >5 times per week | 25 | 7.7 | |

| Depression | Yes | 105 | 32.2 |

| No | 221 | 67.8 | |

| Anxiety | Yes | 92 | 28.2 |

| No | 234 | 71.8 |

| Variable (s) | Social Media Addiction Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p Value from Independent Sample t-Test | p Value from One-Way ANOVA | |

| Gender | <0.001 * | |||

| Male | 19.30 | 3.61 | - | |

| Female | 12.59 | 4.18 | ||

| Age (in years) | 0.006 * | |||

| 18–20 | 15.12 | 4.81 | - | |

| 21–23 | 17.99 | 5.57 | ||

| ≥24 | 14.80 | 4.79 | ||

| Marital Status | 0.920 | |||

| Married | 16.59 | 5.04 | - | |

| Single | 16.73 | 5.71 | ||

| Monthly Family Income | 0.648 | |||

| <3000 SAR | 15.50 | 3.92 | ||

| 3000 to 10,000 SAR | 16.13 | 4.43 | - | |

| 10,001 to 20,000 SAR | 16.19 | 5.18 | ||

| >20,000 SAR | 16.59 | 5.41 | ||

| Education Level | 0.898 | |||

| 2nd year | 16.00 | 3.51 | ||

| 3rd year | 16.22 | 5.38 | ||

| 4th year | 16.85 | 4.83 | - | |

| 5th year | 17.04 | 5.23 | ||

| 6th year | 16.56 | 5.28 | ||

| Intern | 16.11 | 5.08 | ||

| Grade Point Average (GPA) | <0.001 * | |||

| <2.5 | 23.19 | 5.26 | ||

| 2.5–3.49 | 18.65 | 4.22 | ||

| 3.5–4.5 | 17.11 | 3.81 | ||

| >4.5 | 12.26 | 4.59 | ||

| Residence | 0.560 | |||

| Private housing | 16.67 | 5.25 | - | |

| Renting housing | 16.00 | 4.52 | ||

| University compound | 17.31 | 3.79 | ||

| Educational Level of Father | 0.711 | |||

| Illiterate | 14.40 | 4.88 | ||

| Primary level | 16.35 | 3.51 | ||

| Intermediate level | 16.89 | 4.60 | - | |

| Secondary level | 16.61 | 5.31 | ||

| University level | 16.69 | 5.27 | ||

| Educational Level of Mother | 0.543 | |||

| Illiterate | 15.31 | 5.18 | ||

| Primary level | 16.16 | 4.75 | - | |

| Intermediate level | 16.94 | 4.39 | ||

| Secondary level | 17.13 | 4.87 | ||

| University level | 16.67 | 5.31 | ||

| Living with | 0.734 | |||

| Parents | 16.59 | 5.25 | - | |

| Alone | 16.98 | 4.29 | ||

| Friends or relatives | 16.00 | 4.59 | ||

| Current Smoking Status | 0.555 | |||

| Yes | 16.15 | 5.18 | - | |

| No | 16.66 | 5.06 | ||

| Self-reported BMI Status | 0.540 | |||

| Underweight | 15.96 | 6.38 | ||

| Normal weight | 16.29 | 5.11 | ||

| Overweight | 17.16 | 4.91 | - | |

| Obesity | 16.84 | 4.57 | ||

| Physical Activity Level | 0.125 | |||

| No activity | 17.34 | 5.66 | - | |

| <3 times per week | 16.79 | 4.36 | ||

| 3 to 5 times per week | 15.47 | 3.96 | ||

| >5 times per week | 14.76 | 6.23 | ||

| Depression | <0.001 * | |||

| Yes | 20.90 | 4.12 | - | |

| No | 14.56 | 4.11 | ||

| Anxiety | <0.001 * | |||

| Yes | 21.42 | 3.93 | - | |

| No | 14.71 | 4.12 | ||

| Variable (s) | Adjusted Linear Regression Estimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4.52 | 0.37 | 3.79, 5.25 | <0.001 * |

| Female | Reference | |||

| Age (in years) | ||||

| 18–20 | Reference | |||

| 21–23 | −0.13 | 0.50 | −1.12, 0.81 | 0.804 |

| ≥24 | −0.19 | 0.68 | −1.53, 1.15 | 0.704 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 0.88 | 0.87 | −0.83, 2.59 | 0.312 |

| Single | Reference | |||

| Family Income | ||||

| <3000 SAR | Reference | |||

| 3000 to 10,000 SAR | 1.03 | 0.89 | −0.74, 2.80 | 0.251 |

| 10,001 to 20,000 SAR | 1.33 | 0.85 | −0.32, 3.00 | 0.114 |

| >20,000 SAR | 1.37 | 0.86 | −0.33, 3.53 | 0.211 |

| Education Level | ||||

| 2nd year | Reference | |||

| 3rd year | −1.80 | 0.94 | −3.65, 0.05 | 0.056 |

| 4th year | −1.48 | 0.92 | −3.29, 0.32 | 0.107 |

| 5th year | −1.56 | 0.99 | −3.50, 0.49 | 0.116 |

| 6 year | −1.44 | 0.99 | −3.38, 0.49 | 0.145 |

| Intern | −2.92 | 1.07 | −5.01, 0.81 | 0.187 |

| Grade Point Average (GPA) | ||||

| <2.5 | Reference | |||

| 2.5–3.49 | −2.34 | 0.83 | −3.97, −0.71 | 0.005 * |

| 3.5–4.5 | −2.63 | 0.81 | −4.22, −1.04 | 0.001 * |

| >4.5 | −6.15 | 0.87 | −7.86, −4.44 | 0.001 * |

| Residence | ||||

| Private housing | Reference | |||

| Renting housing | 0.09 | 0.53 | −0.95, −0.25 | 0.863 |

| University compound | 1.42 | 0.85 | −0.26, 3.10 | 0.096 |

| Educational Level of Father | ||||

| Illiterate | Reference | |||

| Primary level | 0.96 | 1.17 | −1.35, 3.27 | 0.413 |

| Intermediate level | −0.70 | 1.15 | −2.98, 1.57 | 0.543 |

| Secondary level | 0.15 | 1.27 | −2.06, 2.37 | 0.892 |

| University level | 0.10 | 1.28 | −2.12, 2.32 | 0.927 |

| Educational Level of Mother | ||||

| Illiterate | Reference | |||

| Primary level | 0.96 | 0.81 | −0.64, 2.56 | 0.237 |

| Intermediate level | 0.47 | 0.78 | −1.07, 2.01 | 0.553 |

| Secondary level | 0.1.5 | 0.74 | −1.31, 1.61 | 0.842 |

| University level | 0.55 | 0.69 | −0.83, 1.92 | 0.927 |

| Living with | ||||

| Parents | Reference | |||

| Alone | −1.21 | 0.57 | −2.33, 0.27 | 0.316 |

| Friends, peers and relatives | −2.25 | 0.71 | −2.65, 0.15 | 0.080 |

| Current Smoking Status | ||||

| Yes | −1.25 | 0.54 | −2.31, 0.19 | 0.222 |

| No | Reference | |||

| Self-reported BMI Status | ||||

| Underweight | 0.35 | 0.65 | −0.93, 1.63 | 0.593 |

| Normal weight | Reference | |||

| Overweight | −0.35 | 0.42 | −1.18, 0.47 | 0.400 |

| Obesity | −0.29 | 0.44 | 1.17, 0.57 | 0.499 |

| Physical Activity Level | ||||

| No activity | Reference | |||

| <3 times per week | −0.38 | 0.42 | −1.20, 0.43 | 0.356 |

| 3 to 5 times per week | −1.31 | 0.49 | −2.27, 0.34 | 0.188 |

| >5 times per week | −1.07 | 0.67 | −2.39, 0.26 | 0.114 |

| Depression | ||||

| Yes | 1.85 | 0.92 | 1.10, 3.02 | 0.005 * |

| No | Reference | |||

| Anxiety | ||||

| Yes | 2.79 | 0.93 | 0.95, 4.62 | 0.003 * |

| No | Reference | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfaya, M.A.; Abdullah, N.S.; Alshahrani, N.Z.; Alqahtani, A.A.A.; Algethami, M.R.; Al Qahtani, A.S.Y.; Aljunaid, M.A.; Alharbi, F.T.G. Prevalence and Determinants of Social Media Addiction among Medical Students in a Selected University in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101370

Alfaya MA, Abdullah NS, Alshahrani NZ, Alqahtani AAA, Algethami MR, Al Qahtani ASY, Aljunaid MA, Alharbi FTG. Prevalence and Determinants of Social Media Addiction among Medical Students in a Selected University in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101370

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfaya, Mansour A., Naif Saud Abdullah, Najim Z. Alshahrani, Amar Abdullah A. Alqahtani, Mohammed R. Algethami, Abdulelah Saeed Y. Al Qahtani, Mohammed A. Aljunaid, and Faisal Turki G. Alharbi. 2023. "Prevalence and Determinants of Social Media Addiction among Medical Students in a Selected University in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101370

APA StyleAlfaya, M. A., Abdullah, N. S., Alshahrani, N. Z., Alqahtani, A. A. A., Algethami, M. R., Al Qahtani, A. S. Y., Aljunaid, M. A., & Alharbi, F. T. G. (2023). Prevalence and Determinants of Social Media Addiction among Medical Students in a Selected University in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 11(10), 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101370