Periodontitis in Pregnant Women: A Possible Link to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

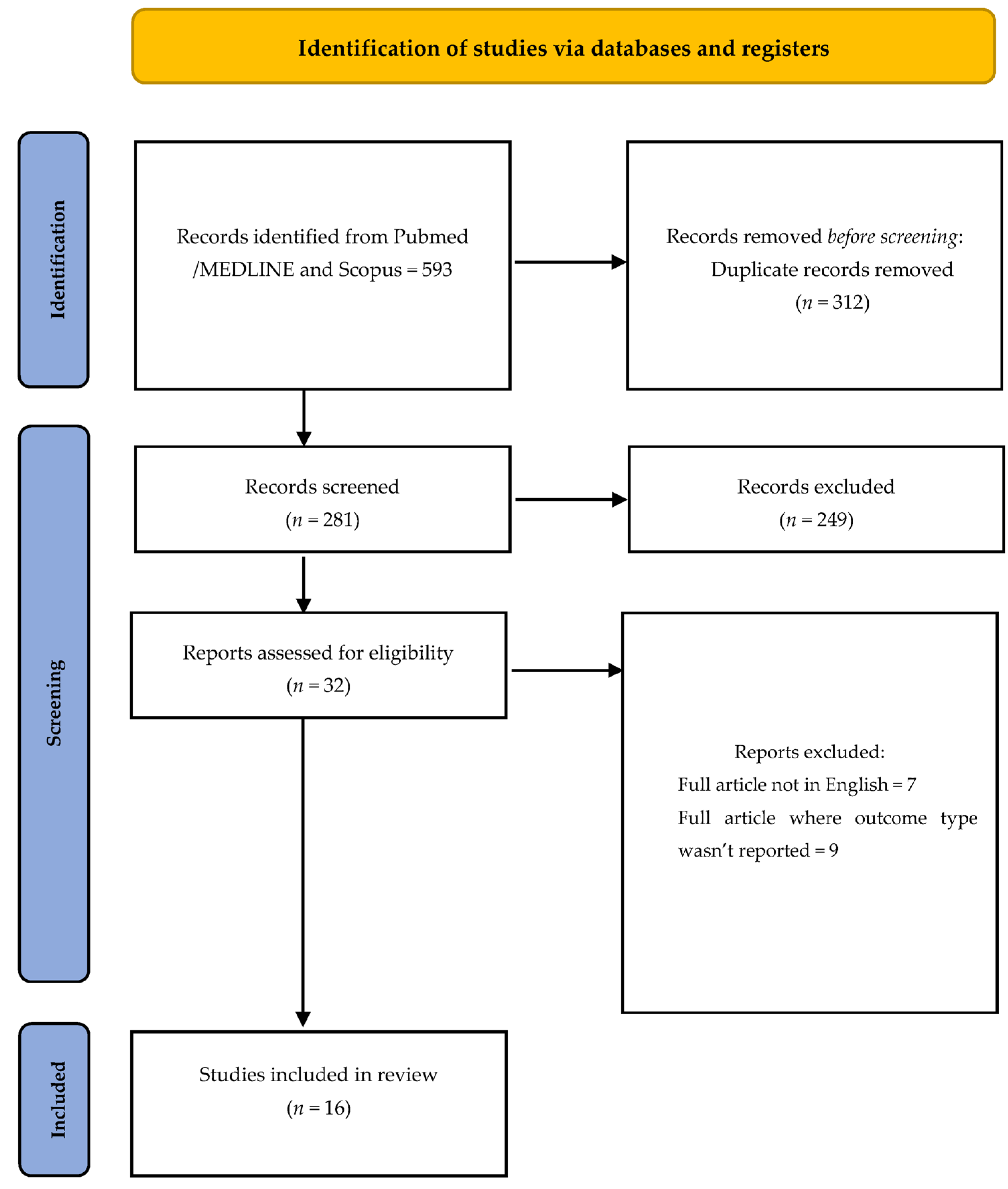

2.4. Research

2.5. Screening and Selection of Articles

2.6. Risk of Bias and Results

3. Results

Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nazir, M.; Al-Ansari, A.; Al-Khalifa, K.; Alhareky, M.; Gaffar, B.; Almas, K. Global Prevalence of Periodontal Disease and Lack of Its Surveillance. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 2146160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Oral Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ameet, M.M.; Avneesh, H.T.; Babita, R.P.; Pramod, P.M. The relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases—Hype or hope? J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, A.; Kassim, N.K.; Zainuddin, S.L.A.; Taib, H.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Ahmad, B.; Hanafi, M.H.; Adnan, A.S. Potential Effects of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy on Periodontal Parameters, Inflammatory Markers, and Kidney Function Indicators in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients with Chronic Periodontitis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, S.; Caton, J.G.; Albandar, J.M.; Bissada, N.F.; Bouchard, P.; Cortellini, P.; Demirel, K.; de Sanctis, M.; Ercoli, C.; Fan, J.; et al. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S219–S229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, C.; Marozio, L.; Tavella, A.M.; Maulà, V.; Carmignani, D.; Curti, A. Response to activated protein C decreases throughout pregnancy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.A.; Akhter, R.; Coulton, K.M.; Vo, N.T.N.; Duong, L.T.Y.; Nong, H.V.; Yaacoub, A.; Condous, G.; Eberhard, J.; Nanan, R. Periodontitis and Preeclampsia in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 2419–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannan, M.; Xiaoping, L.; Ying, J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Progress in related mechanisms and management strategies. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 963956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komine-Aizawa, S.; Aizawa, S.; Hayakawa, S. Periodontal diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 45, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesce, F.; Battisti, C.; Crudo, M. The Inflammatory Cytokine Imbalance for Miscarriage, Pregnancy Loss and COVID-19 Pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 861245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, A.S.; Vhanmane, P.B.; Savitha, B.; Chawla, R.L.; Bagde, H.S. Bacteremia following scaling and root planing: A clinico-microbiological study. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starzyńska, A.; Wychowański, P.; Nowak, M.; Sobocki, B.K.; Jereczek-Fossa, B.A.; Słupecka-Ziemilska, M. Association between Maternal Periodontitis and Development of Systematic Diseases in Offspring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, G.; Basili, M.; Franco, R.; Bollero, P.; Mancini, M.; Gozzo, L.; Romano, G.L.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Gorassini, F.; D’Amico, C.; et al. Periodontal Disease and Pregnancy: Correlation with Underweight Birth. Eur. J. Dent. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, K.; Sivalingam, N. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Malays. Fam. Physician 2007, 2, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rapone, B.; Ferrara, E.; Montemurro, N.; Converti, I.; Loverro, M.; Loverro, M.T.; Gnoni, A.; Scacco, S.; Siculella, L.; Corsalini, M.; et al. Oral Microbiome and Preterm Birth: Correlation or Coincidence? A Narrative Review. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Du, M. Role of Maternal Periodontitis in Preterm Birth. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Chegini, N.; Shiverick, K.T.; Lamont, R.J. Localization of P. gingivalis in preterm delivery placenta. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher-Cobos, G.; Almerich-Torres, T.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Iranzo-Cortés, J.E.; Bellot-Arcís, C.; Ortolá-Siscar, J.C.; Almerich-Silla, J.M. Relationship between Periodontal Condition of the Pregnant Woman with Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Jiang, W.; Hu, X.; Gao, L.; Ai, D.; Pan, H.; Niu, C.; Yuan, K.; Zhou, X.; Xu, C.; et al. Ecological Shifts of Supragingival Microbiota in Association with Pregnancy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, W.; La Torre, G. Health Technology Assessment. Principi, Dimensioni e Strumenti; Seed: Torino, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S.; Macchiarelli, G.; Micara, G.; Aragona, C.; Maione, M.; Nottola, S.A. Ultrastructural and morphometric evaluation of aged cumulus-oocyte-complexes. Ital. J. Anat. Embriol. 2013, 118, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Franzago, M.; Fraticelli, F.; Stuppia, L.; Vitacolonna, E. Nutrigenetics, epigenetics and gestational diabetes: Consequences in mother and child. Epigenetics 2019, 14, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant’Ana, A.C.; Campos, M.R.; Passanezi, S.C.; Rezende, M.L.; Greghi, S.L.; Passanezi, E. Periodontal treatment during pregnancy decreases the rate of adverse pregnancy outcome: A controlled clinical trial. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2011, 19, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenen, Z.; Ataçağ, T. Oral care in pregnancy. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2019, 20, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Cruz, I.; Herrera, D.; Martin, C.; Herrero, A.; Sanz, M. Association between periodontal status and pre-term and/or low-birth weight in Spain: Clinical and microbiological parameters. J. Periodontal. Res. 2013, 48, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggess, K.A.; Beck, J.D.; Murtha, A.P.; Moss, K.; Offenbacher, S. Maternal periodontal disease in early pregnancy and risk for a small-for-gestational-age infant. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddki, N.; Bachok, N.; Hussain, N.H.; Zainudin, S.L.; Sosroseno, W. The association between maternal periodontitis and low birth weight infants among Malay women. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2008, 36, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Basra, M.; Begum, N.; Rani, V.; Prasad, S.; Lamba, A.K.; Verma, M.; Agarwal, S.; Sharma, S. Association of maternal periodontal health with adverse pregnancy outcome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2013, 39, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Martínez-Sahuquillo, A.; Bullón, P. Correlation between infant birth weight and mother’s periodontal status. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, S.K.; Sammel, M.D.; Stamilio, D.M.; Clothier, B.; Jeffcoat, M.K.; Parry, S.; Macones, G.A.; Elovitz, M.A.; Metlay, J. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Is there an association? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 200, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agueda, A.; Ramón, J.M.; Manau, C.; Guerrero, A.; Echeverría, J.J. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenbacher, S.; Boggess, K.A.; Murtha, A.P.; Jared, H.L.; Lieff, S.; McKaig, R.G.; Mauriello, S.M.; Moss, K.L.; Beck, J.D. Progressive periodontal disease and risk of very preterm delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoto-Alson, S.; Tenenbaum, H.; Davideau, J.L. Periodontal diseases, preterm births, and low birth weight: Findings from a homogeneous cohort of women in Madagascar. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.; Ide, M.; Coward, P.Y.; Randhawa, M.; Borkowska, E.; Baylis, R.; Wilson, R.F. A prospective study to investigate the relationship between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcome. Br. Dent. J. 2004, 197, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercan, E.; Eratalay, K.; Deren, O.; Gur, D.; Ozyuncu, O.; Altun, B.; Kanli, C.; Ozdemir, P.; Akincibay, H. Evaluation of periodontal pathogens in amniotic fluid and the role of periodontal disease in pre-term birth and low birth weight. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2013, 71, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreu, G.; Téllez, L.; González-Jaranay, M. Relationship between maternal periodontal disease and low-birth-weight pre-term infants. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobeen, N.; Jehan, I.; Banday, N.; Moore, J.; McClure, E.M.; Pasha, O.; Wright, L.L.; Goldenberg, R.L. Periodontal disease and adverse birth outcomes: A study from Pakistan. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 514.e1–514.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Evid. Based Dent. 2008, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.; Sallum, A.W.; Cecatti, J.G.; Morais, S.S. Periodontal disease and some adverse perinatal outcomes in a cohort of low risk pregnant women. Reprod. Health 2010, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, M.; Africa, C.W.J. Further evidence for periodontal disease as a risk indicator for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Int. Dent. J. 2017, 67, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Maiorani, C.; Morandini, A.; Simonini, M.; Colnaghi, A.; Morittu, S.; Barbieri, S.; Ricci, M.; Guerrisi, G.; Piloni, D.; et al. Assessment of Oral Microbiome Changes in Healthy and COVID-19-Affected Pregnant Women: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, S.W.; Jiang, S.Y. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 623427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobetsis, Y.A.; Graziani, F.; Gürsoy, M.; Madianos, P.N. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 83, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.; Buekens, P.; Fraser, W.D.; Beck, J.; Offenbacher, S. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review. BJOG 2006, 113, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shub, A.; Swain, J.R.; Newnham, J.P. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006, 19, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, G.; Carmagnola, D.; Abati, S.; Luglio, P.F.; Ottolenghi, L.; Villa, A.; Maida, C.; Campus, G. Periodontal disease and preterm birth relationship: A review of the literature. Minerva Stomatol. 2008, 57, 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique-Corredor, E.J.; Orozco-Beltran, D.; Lopez-Pineda, A.; Quesada, J.A.; Gil-Guillen, V.F.; Carratala-Munuera, C. Maternal periodontitis and preterm birth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2019, 47, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambrone, L.; Guglielmetti, M.R.; Pannuti, C.M.; Chambrone, L.A. Evidence grade associating periodontitis to preterm birth and/or low birth weight: I. A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Middleton, P.; Esposito, M.; Glenny, A.M. Treating periodontal disease for preventing adverse birth outcomes in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD005297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, G.; Pihlstrom, B.L. A critical assessment of adverse pregnancy outcome and periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, A.S.; Katoch, V.; Rajguru, S.A.; Rajpoot, N.; Singh, P.; Wakhle, S. Periodontal Disease: A Possible Risk-Factor for Adverse Pregnancy Outcome. J. Int. Oral Health 2015, 7, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, H.E.C.; Stefani, C.M.; de Santos Melo, N.; de Almeida de Lima, A.; Rösing, C.K.; Porporatti, A.L.; Canto, G.L. Effect of intra-pregnancy nonsurgical periodontal therapy on inflammatory biomarkers and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caneiro-Queija, L.; López-Carral, J.; Martin-Lancharro, P.; Limeres-Posse, J.; Diz-Dios, P.; Blanco-Carrion, J. Non-Surgical Treatment of Periodontal Disease in a Pregnant Caucasian Women Population: Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarannum, F.; Faizuddin, M. Effect of periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcome in women affected by periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macek, M.D. Non-surgical periodontal therapy may reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2008, 8, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalowicz, B.S.; Hodges, J.S.; DiAngelis, A.J.; Lupo, V.R.; Novak, M.J.; Ferguson, J.E.; Buchanan, W.; Bofill, J.; Papapanou, P.N.; Mitchell, D.A.; et al. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Maiorani, C.; Milone, A.; Alovisi, M.; Scribante, A. Paraprobiotics in Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy: Clinical and Microbiological Aspects in a 6-Month Follow-Up Domiciliary Protocol for Oral Hygiene. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Maiorani, C.; Molino, D.; Chiesa, A.; Preda, C.; Esposito, F.; Scribante, A. Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Type of Study | (Problem-Population) | Intervent/ Control | Outcomes | Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Cruz et al., 2013 [26] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Population: 170 women were included (mean age 31.9, rangin 20–40) between the 8th to 26th wk of pregnancy | Clinical parameters: PI, BoP, PPD, Gingival recession, Microbiological samples. Demographic and medical data: gestational age, race, maternal weight before pregnancy, maternal height, previous deliveries, previous PTB or LBW, maternal diseases, metabolic or genetic alterations, socio-economic, and educational status | The periodontal condition was not associated with adverse pregnancy: preterm birth, low-weight- birth, preterm and low-birth weight and preterm or low-birth weight. | No |

| Boggess et al., 2006 [27] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and delivery of a small-for-gestational-age infant (less than the 10th percentile for gestational age) Population: 1017 women were included | Clinical parameters: PPD, CAL, BoP. Demographic and medical data: gestational age, maternal weight, previous deliveries less than 37th, deliveries less than 37th, pre-eclampsia, tobacco, alcohol, and drug consumption. | The periodontal condition was associated with delivery of a small-for-gestational-age infant. The small-for-gestational-age rate was higher among women with moderate or severe periodontal disease, compared with those with health or mild disease (13.8% versus 3.2% versus 6.5%, p < 0.001). Moderate or severe periodontal disease was associated with a small-for-gestational-age infant, a risk ratio of 2.3 (1.1 to 4.7). | Yes |

| Saddki et al., 2008 [28] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and low birth weight Population: 472 women were included (ranges from 14 to 46 years old) in the second trimester of pregnancy | Clinical parameters: PPD, CAL, BoP. Demographic and medical data: haemoglobin level, rate of weight gain, history of pre-term birth, history of abortion, history of low-birth weight, socio-economic, and educational status | After adjustment for potential confounders using multiple logistic regression analysis, significant association was found between maternal periodontitis and LBW (OR = 3.84; 95% CI: 1.34–11.05). | Yes |

| Kumar et al., 2013 [29] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Population: 340 women were included (ranges from 18 to 35 years old) at 14–20 weeks of pregnancy | Clinical parameters: BoP, PPD, CAL, Gingival recession. Demographic and medical data: gestational age, socio-economic and educational status, pre-eclampsia, IUGR abruption placenta, type of labor, ode of delivery, neonatal outcome, and birthweight | The study shows a significant association between periodontitis (but not with gingivitis) and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Maternal periodontitis is associated with an increased risk of pre-eclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery and low birthweight infants with odds ratios (95% confidence interval) of 7.48 (2.72–22.42), 3.35 (1.20–9.55), 2.72 (1.30–5.68) and 3.03 (1.53–5.97), respectively. | Yes |

| Marin et al., 2005 [30] | Cross-sectional study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and low birth weight Population: 152 women were included (ranges from 14 to 39 years old) | Clinical parameters: PI, BoP, PPD, CAL. Demographic and medical data: gestational age, educational status, maternal height, previous live births, previous aborts, previous preterm low birth weight, gestational age, maternal gain in weight, infant birth weight, tobacco, alcohol, and drug consumption. | Periodontal disease in pregnant women is statistically associated with a reduction in the infant birth weight. | Yes |

| Srinivas et al., 2009 [31] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes (preterm birth, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, or perinatal death) Population: 152 women were included | Clinical parameters: PPD, CAL. Demographic and medical data: gestational age, maternal height, previous live births, previous abortions, previous preterm deliveries, pre-eclampsia | There was no association between PD and the composite outcome (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.58–1.15; p = 0.24), preeclampsia (AOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.37–1.36; p = 0.30), or preterm birth (AOR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.49–1.21; p = 0.25) after adjusting for relevant confounders. | No |

| Agueda et al., 2008 [32] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and preterm birth, low birth weight, and preterm low birth weight Population: 1296 women were included | Clinical parameters: PI, BoP, PPD, CAL. Demographic and medical data: socio-economic and educational status, residence, ethnicity, body mass index, previous preterm delivery, previous low birth weight, previous miscarriage, pregnancy complications, gestational diabetes, caesarian delivery, antibiotic intake, systemic diseases, and tobacco consumption | The factors involved in many cases of adverse pregnancy outcomes have still not been identified, although systemic infections may play a role. This study found a modest association between periodontitis and PB. Further research is required to establish whether periodontitis is a risk factor for PB and/or LBW. | Yes |

| Offenbacher et al., 2006 [33] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and preterm birth, low birth weight, and preterm low birth weight Population: 1020 women were included before 26 weeks of pregnancy | Clinical parameters: PI, BoP, PPD, CAL. Demographic and medical data: maternal age, maternal weight, previous preterm delivery, medical insurance, tobacco, alcohol, and drug consumption. | Antepartum moderate-severe periodontal disease was associated with an increased incidence of spontaneous preterm births (15.2% versus 24.9%, adjusted RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.2). Similarly, the unadjusted rate of very preterm delivery was 6.4% among women with periodontal disease progression, significantly higher than the 1.8% rate among women without disease progression (adjusted RR 2.4, 95% CI 1.1–5.2). | Yes |

| Rakoto-Alson et al., 2010 [34] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and preterm birth, and low birth weight Population: 204 women were included (25.6 years old) at 20–34 weeks of pregnancy | Clinical parameters: PI, PBI, PPD. Demographic and medical data: socio-economic and educational status, gestational age, birth weight, type of delivery, and previous pregnancy. | Periodontitis (at least three sites from different teeth with clinical AL > or = 4 mm) was significantly associated with PB (p < 0.001), LBW (p < 0.001), and PLBW (p < 0.01). The rates of periodontitis were considerably higher in the PB (78.6%), LBW (77.3%), and PLBW (77.8%) groups than in the full-term (8.6%), normal weight (16.5%), and normal birth (2.7%) groups. | Yes |

| Moore et al., 2004 [35] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and preterm birth, low birth weight, and late miscarriage Population: 3738 women were included (29.5 years old) at 12 weeks of pregnancy | Clinical parameters: PI, BS, PPD, CAL. Demographic and medical data: socio-economic status, ethnicity, previous preterm delivery, previous miscarriage, medications in 1st trimester, antibiotics in 1st trimester, urinary tract infection in 1st trimester, alcohol, and tobacco consumption. | Regression analysis indicated that there were no significant relationships between the severity of periodontal disease and either preterm birth (PTB) or low birth weight (LBW). In contrast, there did appear to be a correlation between poorer periodontal health and those that experienced a late miscarriage. | No |

| Ercan et al., 2013 [36] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and preterm birth, low birth weight, and late miscarriage Population: 50 women undergoing amniocentesis were included | Clinical parameters: PI, BoP, PPD, CAL, GI, microbiological samples. Demographic and medical data: marital and educational status, gestational age, and birth weight | The transmission of some periodontal pathogens from the oral cavity of the mother may cause adverse pregnancy outcomes. The results contribute to an understanding of the association between periodontal disease and PTLBW, but further studies are required to better clarify the possible relationship. | Yes |

| Moreu et al., 2005 [37] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease and preterm birth, and low birth weight Population: 96 women were included (ranges from 18 to 40 years old) | Clinical parameters: PI, GI, PPD. Demographic and medical data: unknown | A relationship was observed between low-weight birth and probing depth measurements, especially the percentage of sites of >3 mm depth, which was statistically significant (p = 0.0038) even when gestational age was controlled for. | Yes |

| Mobeen et al., 2008 [38] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and birth outcomes. Population: 1037 women were included | Clinical parameters: PI, GI, PPD, CAL. Demographic and medical data: ethnicity, educational status, number of pregnancies, previous miscarriage/abortion, previous stillbirth | As various measures of the severity of the periodontal disease increased, both stillbirth and neonatal death increased, accompanied by a non-significant increase in early preterm birth. It is unknown if treatment of periodontal disease either before or during pregnancy would improve these adverse pregnancy outcomes. | No |

| Lopez et al., 2008 [39] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Population: 1404 women were included | Clinical parameters: PPD, CAL, BoP. Demographic and medical data: systemic disease, onset of prenatal care, previous PB, complications of pregnancy, and type of delivery. | This study found a modest association between periodontitis and PB. | Yes |

| Vogt et al., 2010 [40] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Population: 327 women were included (ranges from 18 to 42 years old) before 32 weeks of pregnant | Clinical parameters: PI, GR, PPD, CAL, BoP. Demographic and medical data: socio-demographic variables (age, parity, race/color, years of schooling, marital status, body mass index-BMI-estimated with the pregnancy weight, and any systemic diseases); habit variables (smoking and alcohol consumption); and gestacional variables (number of prenatal visits, bacterial vaginosis, vaginal delivery, and the newborn Apgar scores at the first and fifth minute of life). | PD was associated with a higher risk of PTB (RRadj. 3.47 95%CI 1.62–7.43), LBW (RRadj. 2.93 95%CI 1.36–6.34) and PROM (RRadj. 2.48 95%CI 1.35–4.56), but not with SGA neonates (RR 2.38 95%CI 0.93–6.10). | Yes |

| Turton et al., 2017 [41] | Cohort study | Problem: the association between periodontal disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Population: 443 women were included (ranges from 18 to 42 years old) | Clinical parameters: PI, GI, CAL. Demographic and medical data: age, race, educational level, stage of pregnancy, and medical history. | Significant associations were found between pregnancy outcomes and maternal periodontal index scores (low birth weight and preterm delivery). | Yes |

| Articles | Adequate Sequence Generated | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Incomplete Outcome Data | Registration Outcome Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Cruz et al., 2013 [26] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Boggess et al., 2006 [27] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Saddki et al., 2008 [28] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Kumar et al., 2013 [29] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Marin et al., 2005 [30] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Srinivas et al., 2009 [31] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Agueda et al., 2008 [32] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Offenbacher et al., 2006 [33] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Rakoto-Alson et al., 2010 [34] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Moore et al., 2004 [35] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Ercan et al., 2013 [36] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Moreu et al., 2005 [37] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Mobeen et al., 2008 [38] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Lopez et al., 2008 [39] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Vogt et al., 2010 [40] |  |  |  |  |  |

| Turton et al., 2017 [41] |  |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Butera, A.; Maiorani, C.; Morandini, A.; Trombini, J.; Simonini, M.; Ogliari, C.; Scribante, A. Periodontitis in Pregnant Women: A Possible Link to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101372

Butera A, Maiorani C, Morandini A, Trombini J, Simonini M, Ogliari C, Scribante A. Periodontitis in Pregnant Women: A Possible Link to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101372

Chicago/Turabian StyleButera, Andrea, Carolina Maiorani, Annalaura Morandini, Julia Trombini, Manuela Simonini, Chiara Ogliari, and Andrea Scribante. 2023. "Periodontitis in Pregnant Women: A Possible Link to Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101372