Evaluation of Standard Precautions Compliance Instruments: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

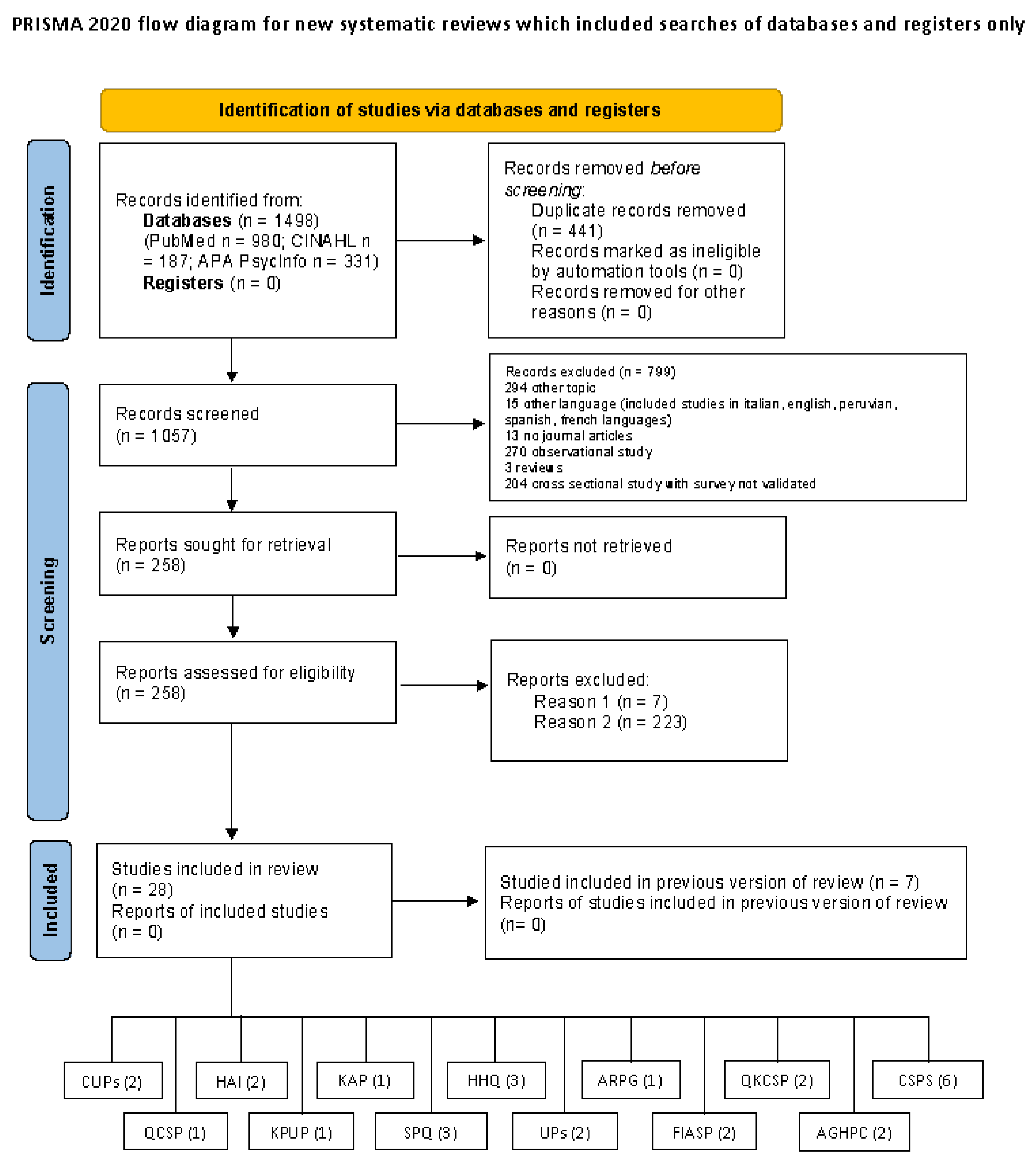

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Qualitative Evaluation of Studies, Psychometric Properties, and Synthesis of Evidence for the Instruments

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Studies Includes in the Review

| Tools | Author/ Year Publication/Country/Type of Study/Concept Assessment | Sample | Items Number/Subscale/Response System | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Other Psychometrics Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUPs | Gershon et al., 1995 [22] Ohio Validation Study Compliance with UP | 1716 healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, technicians, phlebotomists) | 11 items for Compliance with UPs (CUPs) Fields: disposal of sharps, use of needles and barrier-protection, use of gloves, eye protection, protective outer clothing, eating or drinking in potentially contaminated areas. 5-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always”) 14 items for psychosocial factors (PF) 13 items for organizational management factor (OMF) | Total 0.65 (CUPs) Total 0.83 (PF) Total 0.88 (OMF) | ||

| CUPs | Brevidelli & Cianciarullo, 2009 [23] Brazil Validation study Adherence with SP | 270 healthcare workers (physicians and nurses) | 11 items for Compliance with UPs (CUPs) Fields: disposal of sharps, use of needles, and barrier-protection such as gloves, eye protection, protective outer clothing, eating or drinking in potentially contaminated areas. 5-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always”) Dejoy scale | PCA (oblique and orthogonal rotations) 7 factors solution; 54.9% variance explained PCA for safety climate (OMF), 2 factors solution, 47.57% variance explained pretest (a small sample of healthcare workers) | Subdimensions 0.67–0.86 (PCA 7 factors) Subdimensions 0.69–0.80 (PCA 2 factors) | |

| HAI | O’Boyle et al., 2001 [24] Minneapolis Development study Motivation and factor of the HB | 100 nurses | 46 items 6 Subscales: Belief about outcomes, attitudes, referent beliefs, subjective norm, control beliefs, perceived control 7-point Likert (from 1 “Extremely unlikely” to 7 “Extremely likely”) | Face validity, 20 nurse students (pilot testing) | Subscale: 0.64–0.91 | |

| HAI | Villamizar Gomez & Sànchez Pedraza, 2014 [25] Bogotà Validation study Motivation and factor of the HB | 300 nurses | 46 items 6 Subscales: Belief about outcomes, attitudes, referent beliefs, subjective norm, control beliefs, perceived control 7-point Likert (from 1 “Extremely unlikely” to 7 “Extremely likely”) | Face validity (6 nurses with experience in infections; comprehensiveness) EFA (varimax and promax rotation), 8 factors solution, 57.11% variance explained | Total 0.82 Subscale 0.44–0.90 | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) Test-retest (recall period 5.7 weeks); r < 0.50, except hand condition= 0.54) Criterion validity (HAI and Attitudes Regarding Practice Guidelines), r < 0.30 |

| UPs | Chan et al., 2002 [26] Hong Kong Development study Knowledge and compliance with UP | 450 nurses | 26 items Two scales: nurses’ knowledge (11 items) and nurses’ compliance (15 items) Fields: use of protective devices, disposal of sharps, disposal of waste, decontamination of spills and used articles, prevention of cross infection from person to person, contact with body fluids including tears, sweat, saliva, urine, and feces. True/false for nurses’ knowledge 4-point Likert for nurses’ compliance (from 0 “never” to 3 “always”) | Content validity (panel with 8 experts of the infection control unit, CVI = 88.6%) | Total 0.72 | |

| UPs | Lam et al., 2012 [27] Hong Kong Validation study Compliance with UP | 440 nurses | 15 items Only nurses’ compliance UPs Fields: use of protective devices, disposal of sharps, disposal of waste, decontamination of spills and used articles, and prevention of cross-infection from person to person 4-point Likert (from 0 “never” to 3 “always”) | Face validity (15 nursing students; 100% understandability) | Total 0.80 | Reliability (recall period 2 weeks): ICC: r = 0.83, p < 0.001, 95% CI 0.77–0.87 Hypotheses testing (known-groups technique): students and nurses, 60.2 and 69.5, respectively, t = −9.00, p < 0.001 |

| ARPG | Larson, 2004 [28] New York Development study General and specifically attitude with Hand Hygiene Guideline | 10 physicians and 11 nurses | 36 items Subscales: general attitudes guideline (18 items), specifically attitudes with Hand Hygiene Guideline (18 items) 6-point Likert (from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 6 “Strongly agree”) | Content validity (panels with more than 12 experts; readability, understandability, ease of response) | Total 0.80 | Test-retest for Part 1 (recall period 2 weeks); r = 0.80 |

| KPUPs | Motamed et al., 2006 [29] Iran Development study Knowledge and practice with UP | 540 healthcare workers and medical students | 18 items 2 Subscales: Knowledge (10 items) and practices (8 items) Fields: Understanding of precautions, disposal of sharps, contact with vaginal fluid, handwashing, disposal of needles, and glove, mask, and gown usage Dichotomous response (True/False for Knowledge and Agree/Disagree for Practice subscales) | Content and face validity (panel experts of the infection control committee of the two hospitals) Face validity (pilot testing with 20 subjects, feasibility, and internal consistency) | Total 0.71 | |

| KAPs | Chan et al., 2008 [30] China Development study Knowledge, attitudes and practice of operating room staff with SP and TBP | 113 nurses and non-medical staff | 25 items 3 subscales: Knowledge (4 items), Attitudes (11 items) and Practices (10 items) Fields: PPE, solid waste disposal, environmental cleaning and disinfection measures and safety measures following occupational exposure to biological material For knowledge scale: multiple-choice questions For attitude subscale: 5-point Likert (from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”) For Practices subscales: 5-point scale (from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always”) | Content validity (panel of two experts, CVI 0.97) EFA, 3 factors solution, 62.4% variance explained | Subdimension 0.71–0.89 | Test-retest (recall period 2 weeks; 14 subject); r = 0.80 Hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent validity) between attitudes and practices (r = 0.39, p < 0.05) |

| HHQ | Van de Mortel, 2009 [31] Australia Development study Knowledge, beliefs and practices in HH | 59 student nurses | 36 items Subscales: Hand hygiene belief scale (HBS, 19 items), Hand Hygiene Practices Inventory (HHPI, 14 items), Hand Hygiene Importance Scale (HIS, 3 items) Multiple choice per HBS 5-point Likert for HHPI and HIS (from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”) | Face validity (pilot testing with 14 nursing students; comprehension and redundancy) | Subscale 0.74–0.80 | Test-retest (recall period 2 weeks; 14 subject); r > 0.79 for each subscale) |

| HHQ | Najafi Ghezeljeh et al., 2015 [32] Iran Validation study Knowledge, beliefs and practices in HH | 60 student nurses | 36 items Scales: Hand hygiene belief scale (HBS, 19 items), Hand Hygiene Practices Inventory (HHPI, 14 items), Hand Hygiene Importance Scale (HIS, 3 items) Multiple choice per HBS 6-point Likert for HHPI and HIS (from 0 “Never” to 5 “Always”) | Content validity (panel of 10 experts, comprehensibility) Face validity (20 student nurses, comprehensibility) | Total 0.80 Subscales 0.70–0.90 | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) Test-retest (recall period 7–10 days); r > 0.51 (for each subscale); from 0.51 to 0.61 Reliability: ICC: HIS = 0.78 (0.63–0.87), HBS = 0–70 (0.60–0.81), HHPI = 0.85 (0.73–0.91) |

| HHQ | Birgili et al., 2019 [33] Turkey Validation study Knowledge, beliefs and practices in HH | 595 nursing and physiotherapy students | 36 items Background theory: Social cognitive theory of Bandura Subscales: Hand hygiene belief scale (HBS, 19 items), Hand Hygiene Practices Inventory (HHPI, 14 items), Hand Hygiene Importance Scale (HIS, 3 items) Multiple choice per HBS 5-point Likert for HHPI and HIS (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) | Content and face validity (panel of experts, comprehensibility, CVI = 0.80; CVI from 0.77 to 0.86) Face validity (15 nursing student and academic staff, comprehensibility) CFA: 5 factor solution CFI 0.97 RMSEA 0.064 | Total 0.88 Subscales 0.74–0.95 | Cross Cultural Validity (Forward and backward translation) Test-retest (recall period 2 weeks); r > 0.51 (for each subscale); from 0.51 to 0.61 Hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent validity) between each pair of subscales (from 0.450 to 0.547; p < 0.001) |

| QKCSP | Luo et al., 2010 [34] China Development study Knowledge and compliance with SP | 1444 nurses | 40 items Two scales: knowledge SPs (QKSP) and compliance SPs (QASP) Fields: Hand hygiene, PPE, safe handling of patient care equipment, safe practices in the handling of piercing and cutting objects and safety measures following occupational exposure to biological material 3-point Likert for Knowledge SPs (yes, no and uncertain/unknown) 4-point Likert for Compliance SPs (from 0 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Content and face validity QKSP (0.98) Content and face validity QASP (0.98) | Total QKSP 0.92 Total QASP 0.93 | Test-retest QKSP (recall period not indicated); r = 0.86 Test-retest QASP (recall period not indicated); r = 0.87 |

| QKCSP | Valim et al., 2013 [35] Brazil Validation Study Knowledge and compliance with SP | 42 nurses | 40 items Two scales: knowledge SPs (QKSP) and compliance SPs (QASP) Fields: Hand hygiene, PPE, safe handling of patient care equipment, safe practices in the handling of piercing and cutting objects and safety measures following occupational exposure to biological material 3-point Likert for Knowledge SPs (yes, no and uncertain/unknown) 4-point Likert for Compliance SPs (from 0 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Content validity (panel of 12 experts; semantic evaluation) Face validity (30 nurses; understand and clarity) | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) | |

| CSPS | Lam, 2011 [36] Hong Kong Development study Compliance with SP | 193 nurses | 20 items Fields: Use protective devices, disposal and sharp, disposal of waste, decontamination, prevention cross infection 4-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Content validity (panel with six experts on the infection theme, relevance, and adequacy, CVI = 0.90, CVI-item = 0.83–1.00) Face validity (72 nurses and nursing students, 100% understandable words and style) | Total 0.73 | |

| CSPS | Lam, 2014 [37] Hong Kong Validation study Compliance with SP | 453 nurse and nursing students | 20 items Fields: Use protective devices, disposal and sharp, disposal of waste, decontamination, prevention cross infection 4-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Reviewed by 19 international experts with narrative feedback (relevance and globally applicable) | Total 0.73 | Reliability (recall period 2 weeks and 3 months): ICC: r = 0.79, p < 0.001 (2 weeks) ICC: r = 0.74, p < 0.001 (3 months) Criterion validity (CSPS and UPs), r = 0.76, p < 0.001 |

| CSPS-A Arabic version | Cruz et al., 2016 [38] Saudi Arabia Validation study Compliance with SP | 230 nurses | 20 items Fields: Use protective devices, disposal and sharp, disposal of waste, decontamination, prevention cross infection 4-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Content validity (panel of 5 experts in infection control; relevance; CVI = 1) Pilot-testing (40 nurses, difficult and understand) | Total 0.89 | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) Reliability (recall period 2 weeks): ICC = 0.88 Hypotheses testing (known-groups technique):

|

| CSPS-PB Portughese-Brasilian version | Pereira et al., 2017 [39] Brazil Validation study Compliance with SP | 300 nurses | 20 items Fields: Use protective devices, disposal and sharp, disposal of waste, decontamination, prevention cross infection 4-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Content validity (panel of 7 experts; relevance, comprehensiveness, comprehensibility) Pilot-test (50 nurses, comprehensibility) | Total 0.61 | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) Reliability (recall period 2 weeks): ICC = 0.85, p < 0.001 |

| CSPS-It Italian version | Donati et al., 2019 [3] Italy Validation study Compliance with SP | 253 nurses | 20 items Fields: Use protective devices, disposal and sharp, disposal of waste, decontamination, prevention cross infection 4-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Content validity (panel of 6 experts; relevance, comprehensiveness, comprehensibility, CVI = 0.95) CFA (unidimensional model) CFI = 0.90 TLI = 0.87 RMSEA = 0.09 | Total 0.84 | Cross-cultural validity (Forward and backward translation) Reliability (recall period 2 weeks): ICC = 0.86, p < 0.001 Hypotheses testing (known-groups technique): compliance of nurses who attended a training course on SPs was significantly higher (p < 0.001) |

| CSPS-T Turkey version | Samur et al., 2020 [5] Turkey Validation study Compliance with SP | 411 nurses | 20 items Fields: Use protective devices, disposal and sharp, disposal of waste, decontamination, prevention cross infection 4-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 4 “Always”) | Total 0.71 | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) Reliability (recall period 2 weeks): ICC = 0.84, CI 95% 0.77–0.90, p < 0.001 | |

| QCSP | Valim et al., 2015 [40] Brasil Validation study Compliance with SP | 121 nurses | 20 items Fields: Hand hygiene, protective equipment (gloves, mask, goggles, and apron) and disposable equipment (hat and shoes), use and disposal of needles, blades, and sharps in specific containers, the procedure in the case of injuries from potentially contaminated sharps 5-point Likert (from 0 “never” to 4 “always”) | Total 0.80 | Reliability (recall period 2 weeks): ICC: r = 0.973, 95% CI 0.93–0.99, p < 0.001 Hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent validity) between compliance to SP and higher nurses’ perceived safety (r = 0.614; p < 0.001) Hypotheses testing for construct validity (discriminant validity) between compliance to SP and perception of obstacles to follow precautions (r = −0.537; p < 0.001) | |

| SPQ | Michinov et al., 2016 [41] France Development study Compliance with SP | 331 healthcare workers (nurses, physicians, and medical students) | 24 items 7 Subdimension: Attitude, social influence, facilitating organization, exemplary behavior, organizational constraint, individual constraint, intention Fields: prevention of infection, influence and exemplary behavior of colleagues, facilities available in a health care setting, training and reminders in the use of SP, the occurrence of unanticipated events, lack of time, heavy workload, lack of knowledge about SP, personal beliefs, problems related to use of equipment 5-point Likert (format not indicated) | Face validity (panel of 5 experts; understand and clarity of items) Face validity (14 nurses; reformulation and redundant items) EFA 7 factors solution, 66.51% variance explained | Total 0.78 Subdimension 0.71–0.88 | |

| SPQ | Pereira-Avila et al., 2019 [42] Brazil Validation study Compliance SP | 21 healthcare workers (physicians and nurses) | 24 items 7 Subdimension: Attitude, social influence, facilitating organization, exemplary behavior, organizational constraint, individual constraint, intention Fields: prevention of infection, influence and exemplary behavior of colleagues, facilities available in a health care setting, training and reminders in the use of SP, the occurrence of unanticipated events, lack of time, heavy workload, lack of knowledge about SP, personal beliefs, problems related to use of equipment 5-point Likert (format not indicated) | Content and face validity (panel of 5 experts; clarity, understanding, and relevance, CVI 0.96) Semantic evaluation (21 healthcare workers) | Cross-cultural validity (forward and backward translation) | |

| SPQ | Luna et al., 2020 [43] Brazil Validation study Compliance SP | 300 healthcare workers (physicians and nurses) | 24 items 7 Subdimension: Attitude, social influence, facilitating organization, exemplary behavior, organizational constraint, individual constraint, intention Fields: prevention of infection, influence and exemplary behavior of colleagues, facilities available in a health care setting, training and reminders in the use of SP, the occurrence of unanticipated events, lack of time, heavy workload, lack of knowledge about SP, personal beliefs, problems related to use of equipment 5-point Likert (format not indicated) | EFA (varimax rotation), 7 factors solution; 65.75% variance explained | Total 0.71 Subdimension 0.69–0.83 | Hypotheses testing (known-groups technique): nurses significantly correlation with intention (p = 0.000) and individual constraint (p = 0.041) respect physicians and nursing technicians |

| FIASP | Bouchoucha & Moore, 2019 [44] Australia Development study Adherence SP | 684 nurses | 29 items Subdimensions: Leadership, justification, contextual cues, culture/practice, judgment 5-point Likert (from 0 “Not at all” to 4 “Very much”) | PCA (oblique rotation), 5 factors solution, 48% variance explained CFA, 5 factors solution GFI = 0.889 RMSEA = 0.038 SRMR = 0.054 | Subdimension 0.61–0.85 | Reliability (recall period 4 weeks): ICC: range r = 0.69–0.85, p < 0.001 |

| FIASP | Bouchoucha et al., 2021 [45] Australia Validation study Adherence SP | 321 undergraduate nursing students | 29 items Subdimensions: Leadership, justification, contextual cues, culture/practice, judgment 5-point Likert (from 0 “Not at all” to 4 “Very much”) | Face validity (panel of 6 experts; comprehensiveness) PCA (oblique rotation), 4 factors solution, 53.82% variance explained CFA, 4 factors solution CFI = 0.89 RMSEA = 0.05 SRMR = 0.08 | Subdimension 0.79–0.80 | |

| AGHPC | Meneguin et al., 2022 [46] Brazil Development study Adherence Good Practices for COVID-19 | 35 healthcare workers | 47 items 3 subdimensions: personal, organizational, and psychosocial 5-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always”) | Content and face validity (panel of 7 experts; clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness; CVI 0.99) Face validity (35 healthcare workers; understanding) | ||

| AGHPC | Meneguin et al., 2022 [47] Brazil Development study Adherence Good Practices for COVID-19 | 307 healthcare workers | 47 items 3 subdimensions: personal, organizational, and psychosocial 5-point Likert (from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always”) | EFA (oblique rotation) 3 factors solution; 78.2% variance explained CFA, 3 factors solution CFI = 0.996 TLI = 0.995 RMSEA = 0.072 SRMR = 0.082 | Total 0.96 Subdimension 0.61–0.95 | Hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent validity) between total score and its domains (r 0.66–0.90; p < 0.001) |

3.2. Methodological Quality, Overall Rating, and GRADE’s Quality of Evidence

3.3. Psychometric Properties, Overall Rating and GRADE’s Quality of the Evidence

3.4. Compliance Standard Precaution Instruments

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Multimedia: Searching Filter of PubMed

|

|

|

|

References

- Siegel, J.D.; Rhinehart, E.; Jackson, M.; Chiarello, L.; Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am. J. Infect. Control 2007, 35, S65–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faouri, I.; Okour, S.H.; Alakour, N.A.; Alrabadi, N. Knowledge and compliance with standard precautions among registered nurses: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 62, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, D.; Biagioli, V.; Cianfrocca, C.; De Marinis, M.G.; Tartaglini, D. Compliance with Standard Precautions among Clinical Nurses: Validity and Reliability of the Italian Version of the Compliance with Standard Precautions Scale (CSPS-It). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dobrina, R.; Donati, D.; Giangreco, M.; De Benedictis, A.; Schreiber, S.; Bicego, L.; Scarsini, S.; Buchini, S.; Kwok, S.W.H.; Lam, S.C. Nurses’ compliance to standard precautions prior to and during COVID-19. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/inr.12830 (accessed on 12 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Samur, M.; Intepeler, S.S.; Lam, S.C. Adaptation and validation of the Compliance with Standard Precautions Scale amongst nurses in Turkey. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, T. Guideline Implementation: Transmission-Based Precautions. AORN J. 2019, 110, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, V.R.; Leis, J.A.; Trbovich, P.; Agnihotri, T.; Lee, W.; Joseph, B.; Glen, L.; Avaness, M.; Jinnah, F.; Salt, N.; et al. Improving healthcare worker adherence to the use of transmission-based precautions through application of human factors design: A prospective multi-centre study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- CDC Prevention Guidelines Database. Update: Revised Public Health Service Definition of Persons Who Should Refrain from Donating Blood and Plasma—United States. MMWR 2015, 34, 547–548. Available online: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/prevguid/m0000606/m0000606.asp (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Garner, J.S.; the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1996, 17, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagita, R.W.; Pangastuti, H.S.; Alim, S. Factors Affecting Nurses’ Compliance in Implementing Standard Precautions in Government Hospital in Yogyakarta. Indones Contemp. Nurs. J. 2019, 3. Available online: http://journal.unhas.ac.id/index.php/icon/article/view/4972 (accessed on 12 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zeb, S.; Ali, T.S. Factors associated with the compliance of standard precaution; review article. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 713–717. [Google Scholar]

- Livshiz-Riven, I.; Hurvitz, N.; Ziv-Baran, T. Standard Precaution Knowledge and Behavioral Intentions Among Students in the Healthcare Field: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 30, e229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Fischhoff, B.; Lichtenstein, S. Facts and Fears: Understanding Perceived Risk. In Societal Risk Assessment: How Safe is Safe Enough? Schwing, R.C., Albers, W.A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sulzbach-Hoke, L.M. Risk Taking by Health Care Workers. Clin. Nurse Spec. 1996, 10, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagliate, P.D.C.; Nogueira, P.C.; de Godoy, S.; Mendes, I.A.C. Measures of knowledge about standard precautions: A literature review in nursing. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2013, 13, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valim, M.D.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Richart-Martínez, M.; Sanjuan-Quiles, Á. Instruments for evaluating compliance with infection control practices and factors that affect it: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 1502–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Jansma, E.P.; Riphagen, I.I.; de Vet, H.C.W. Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, Y.; Chang, H.; Feng, J. Appraisal and evaluation of the instruments measuring the nursing work environment: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershon, R.R.; Vlahov, D.; Felknor, S.A.; Vesley, D.; Johnson, P.C.; Delcios, G.L.; Murphy, L.R. Compliance with universal precautions among health care workers at three regional hospitals. Am. J. Infect. Control 1995, 23, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevidelli, M.M.; Cianciarullo, T.I. Psychosocial and organizational factors relating to adherence to standard precautions. Rev. Saúde Pública 2009, 43, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Boyle, C.A.; Henly, S.J.; Duckett, L. Nurses’ motivation to wash their hands: A standardized measurement approach. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2001, 14, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamizar Gómez, L.; Sánchez Pedraza, R. Validación del Handwashing Assessment Inventory en un hospital universitario de Bogotá. Index. Enferm. 2014, 23, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Molassiotis, A.; Eunice, C.; Virene, C.; Becky, H.; Chit-ying, L.; Pauline, L.; Frances, S.; Ivy, Y. Nurses’ knowledge of and compliance with universal precautions in an acute care hospital. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, S.C.; Ho, Y.-C.; Chan, J.T.-W.; Lam, G.W.-C.; Au, M.-F.; Sham, C.K.-N.; Hui, W.-S.; Lai, E.I.-Y.; Or, C.W.-T.; Chan, F.-H.; et al. Psychometric testing of compliance with universal precautions scale in clinical nursing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E. A tool to assess barriers to adherence to hand hygiene guideline. Am. J. Infect. Control 2004, 32, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed, N.; Baba Mahmoodi, F.; Khalilian, A.; Peykanheirati, M.; Nozari, M. Knowledge and practices of health care workers and medical students towards universal precautions in hospitals in Mazandaran Province. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2006, 12, 653–661. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/117133 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Chan, M.F.; Ho, A.; Day, M.C. Investigating the knowledge, attitudes and practice patterns of operating room staff towards standard and transmission-based precautions: Results of a cluster analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mortel, V. Development of a Questionnaire to Assess Health Care Students’ Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 26, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi Ghezeljeh, T.; Khosravi, M.; Tolouei Pourlanjarani, T. Translating and evaluating psychometric properties of hand hygiene questionnaire-Persian version. J. Client-Cent. Nurs. Care 2015, 1, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Birgili, F.; Baybuga, M.S.; Ozkoc, H.; Kuru, O.; Van de Mortel, T.; Tümer, A. Validation of a Turkish translation of The Hand Hygiene Questionnaire. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2019, 25, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; He, G.P.; Zhou, J.W.; Luo, Y. Factors impacting compliance with standard precautions in nursing, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e1106–e1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valim, M.D.; Marziale, M.H.P. Cultural adaptation of “Questionnaires for Knowledge and Compliance with Standard Precaution” to Brazilian Portuguese. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2013, 34, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, S.C. Universal to standard precautions in disease prevention: Preliminary development of compliance scale for clinical nursing. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.C. Validation and Cross-Cultural Pilot Testing of Compliance with Standard Precautions Scale: Self-Administered Instrument for Clinical Nurses. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.P.; Colet, P.C.; Al-otaibi, J.H.; Soriano, S.S.; Cacho, G.M.; Cruz, C.P. Validity and reliability assessment of the Compliance with Standard Precautions Scale Arabic version in Saudi nursing students. J. Infect. Public Health 2016, 9, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, F.M.V.; Lam, S.C.; Gir, E. Cultural Adaptation and Reliability of the Compliance with Standard Precautions Scale (CSPS) for Nurses in Brazil. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2017, 25, e2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valim, M.D.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Hayashida, M.; Rocha, F.L.R.; Santos, J.L.F. Validity and reliability of the Questionnaire for Compliance with Standard Precaution. Rev. Saúde Pública 2015, 49, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michinov, E.; Buffet-Bataillon, S.; Chudy, C.; Constant, A.; Merle, V.; Astagneau, P. Sociocognitive determinants of self-reported compliance with standard precautions: Development and preliminary testing of a questionnaire with French health care workers. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Ávila, F.M.V.; Michinov, E.; da Costa de Luna, T.D.; Conde, P.d.S.; Pereira-Caldeira, N.M.V.; Góes, F.G.B. Standard precautions questionnaire: Adaptação cultural e validação semântica para profissionais de saúde no brasil. Cogit. Enferm. 2019, 24, e59014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- da Costa de Luna, T.D.; Pereira-Ávila, F.M.V.; Brandão, P.; Michinov, E.; Góes, F.G.B.; Caldeira, N.M.V.P.; Gir, E. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Standard Precautions Questionnaire for health professionals in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20190518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchoucha, S.L.; Moore, K.A. Factors Influencing Adherence to Standard Precautions Scale: A psychometric validation. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bouchoucha, S.L.; Kilpatrick, M.; Lucas, J.J.; Phillips, N.M.; Hutchinson, A. The Factors Influencing Adherence to Standard Precautions Scale—Student version (FIASP-SV): A psychometric validation. Infect. Dis. Health 2021, 26, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguin, S.; Pollo, C.F.; Melchiades, E.P.; Ramos, M.S.M.; de Morais, J.F.; de Oliveira, C. Scale of Adherence to Good Hospital Practices for COVID-19: Psychometric Properties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguin, S.; Pollo, C.F.; Garuzi, M.; Morais JF de Reche, M.C.; Melchiades, E.P.; Coró, C.; Segalla, A.V.Z. Creation and content validity of a scale for assessing adherence to good practices for COVID-19. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 75, e20210223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for Prevention of HIV Transmission in Health-Care Settings; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1987; 16p.

- Bandura, A. Organisational Applications of Social Cognitive Theory. Aust. J. Manag. 1988, 13, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, K.H.; Cohen, M.L. Standard Precautions—A New Approach to Reducing Infection Transmission in the Hospital Setting. J. Infus. Nurs. 1997, 20, S11. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, M.; Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. 1974. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/109019817400200403?journalCode=heba (accessed on 12 March 2023).

| Tool | Relevance | Comprehensiveness | Comprehensibility | Overall Content Validity | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Other Measurement | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGHPC | +/L | +/L | +/L | +/L | −/L | −/L | Hypothesis testing +/L | B |

| ARPG | +/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | +/L | Reliability +/L | B | |

| CSPS | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | −/M | +/M | Reliability +/M Cross-cultural validity +/M Hypothesis testing −/M | A |

| CUPs | +/VL | ±/VL | ?/VL | ±/VL | -/M | -/M | C | |

| FIASP | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ?/M | +/M | Reliability +/M | B |

| HAI | +/M | ±/M | +/M | ±/M | −/L | −/L | Cross-cultural validity +/L Criterion validity −/L Reliability −/L | B |

| HHQ | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | Cross-cultural validity +/M Reliability ?/M Hypothesis testing −/M | A |

| KAPs | +/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | −/L | +/L | Reliability +/L Hypothesis testing −/L | B |

| KPUPs | ±/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | −/M | C | ||

| QCSP | +/VL | +/VL | +/VL | +/VL | +/L | Hypothesis testing +/L Reliability +/L | A | |

| QKCSP | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | +/L | Reliability +/L Cross-cultural validity +/L | B | |

| SPQ | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | −/M | +/M | Hypothesis testing +/M Cross-cultural validity +/M | A |

| UPs | +/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | +/L | Reliability +/L Hypothesis testing +/L | B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lommi, M.; De Benedictis, A.; Porcelli, B.; Raffaele, B.; Latina, R.; Montini, G.; Tolentino Diaz, M.Y.; Guarente, L.; De Maria, M.; Ricci, S.; et al. Evaluation of Standard Precautions Compliance Instruments: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101408

Lommi M, De Benedictis A, Porcelli B, Raffaele B, Latina R, Montini G, Tolentino Diaz MY, Guarente L, De Maria M, Ricci S, et al. Evaluation of Standard Precautions Compliance Instruments: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology. Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101408

Chicago/Turabian StyleLommi, Marzia, Anna De Benedictis, Barbara Porcelli, Barbara Raffaele, Roberto Latina, Graziella Montini, Maria Ymelda Tolentino Diaz, Luca Guarente, Maddalena De Maria, Simona Ricci, and et al. 2023. "Evaluation of Standard Precautions Compliance Instruments: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101408