How Were Return-of-Service Schemes Developed and Implemented in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Reflexivity

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Understanding RoS Schemes in Three Southern African Countries (Context and Content)

3.1.1. Types of Schemes

3.1.2. Aim of the Programmes

- (a)

- Address critical skills shortages and strengthen government capacity

GBL1: For example, we refer to South Africa, we refer to private hospitals, we refer to medical laboratories… So, for us it’s an issue of not having the right skilled manpower. …you don’t have to refer for cancer or something like that, …we can do on our own home ground. So, that within four or five years, uh, let me say ten years at least, we are able to be sustainable. We don’t have to refer people for cardiology…

PP2: So, I study the …dynamics in the labour market, and then say for the labour market to be efficient and effective, what does it require? Obviously, one of the major… inputs into it, it’s human resources. … that’s where then we have to then have very clear human resource planning and development strategies, …skills, uh, requirements in the short term…, in the medium term, in the long-term…

- (b)

- Professionals who are relevant and up-to date

PP1: I guess the objectives would be for government to gain because we live in an ever-changing world, so, we need to constantly have skills that are…, on par with the rest of the world (sic).

- (c)

- Human resource development and career pathing

- (d)

- Improve employability prospects for citizens

PP2: So, at independence you know the country had a desire to fill, uh, strategic positions of the economy with, uh, qualified emaSwati [Swati nationals]. So, uhm, there was then a targeted, uhm programme to train emaSwati [Swati nationals] so that when they come back, they will take up their positions, and the policy then was called local, it was called a localisation policy.

- (e)

- Strengthen management and population health skills

- (f)

- Fulfill national political mandates

PP2: So, this was like the start…, the span of this study was like 5 years. So, uh, that priority, identification came to an end this past year, 2020. So, we have since appointed a consultant now to undertake a new study, you know, to project… the training needs for the next five years again.

3.1.3. Who Are the Beneficiaries?

DS1: …we don’t want students knowing our criteria because sometimes, we try to share the criteria with them… But you know how students are, if you didn’t succeed, now… they go back to criteria. Now I passed more than whoever blah blah blah.

GBL1: We are trying to cater for everybody. You know? So, pregnancy is not no longer an issue.

3.1.4. What Are the Beneficiary Obligations?

PP1: Officers who are sent on training are expected back in the positions they were prior to leaving. We do not allow for officers to change professions under this facility.

3.1.5. Are There Possibilities for Contract Deviations?

GBL1: I think that one is discretion, the Board will decide whether you sign another bond, because this one would have been five years and then you sign another one which is for a different programme that becomes additional two years. …it’s normally, uh, a special dispensation because we don’t always allow for somebody to continue, uh, immediately after completing. You must come back, serve a certain period of time then continue with another qualification.

3.1.6. Origins of the Schemes

DS1: …they were introduced in 1978 and they have never been reviewed. We are also, we are only now in the process of reviewing them…

3.1.7. Policy Development Framework

3.1.8. Countries of Study

GBL2: …we send…, these employees, around the world to get the gist of these different…, academic fields…, within the different countries that we may have, or we would like them sent to…

FZ1: So, we have got medical students in Cuba right now. Right now, we have thirteen. We don’t have a lot of students there as much as South Africa has. …Cuba is strictly medicine. But then we also have students who do medicine under the top achievers’ program. This… programme is specifically for high excelling students. …who are at the local institutions doing BSc, Bachelor of Science year one…

DS1: So, Lesotho went to the extent of arranging with the government of South Africa for certain institutions to give slots to a maximum of five students per institution for medicine.

PP2: …we have bilateral, uhm, skills development programmes with those countries. Like Cuba…, Russia…, Taiwan. So, we select students, you know, yeah, to benefit from this, uh, bilateral, uh, skills development programmes but, uh, there are those like for example in Ukraine, you know most of those students in Ukraine, they just go there, yeah, and then when, they are there, yeah, of course we do ascertain if the quality of education they are getting is up to standard… If like they are best of our minds (sic) and they want to go and pursue their training, in those countries, and we think they qualify and the universities they are training at are good enough, then we support them wherever they are.

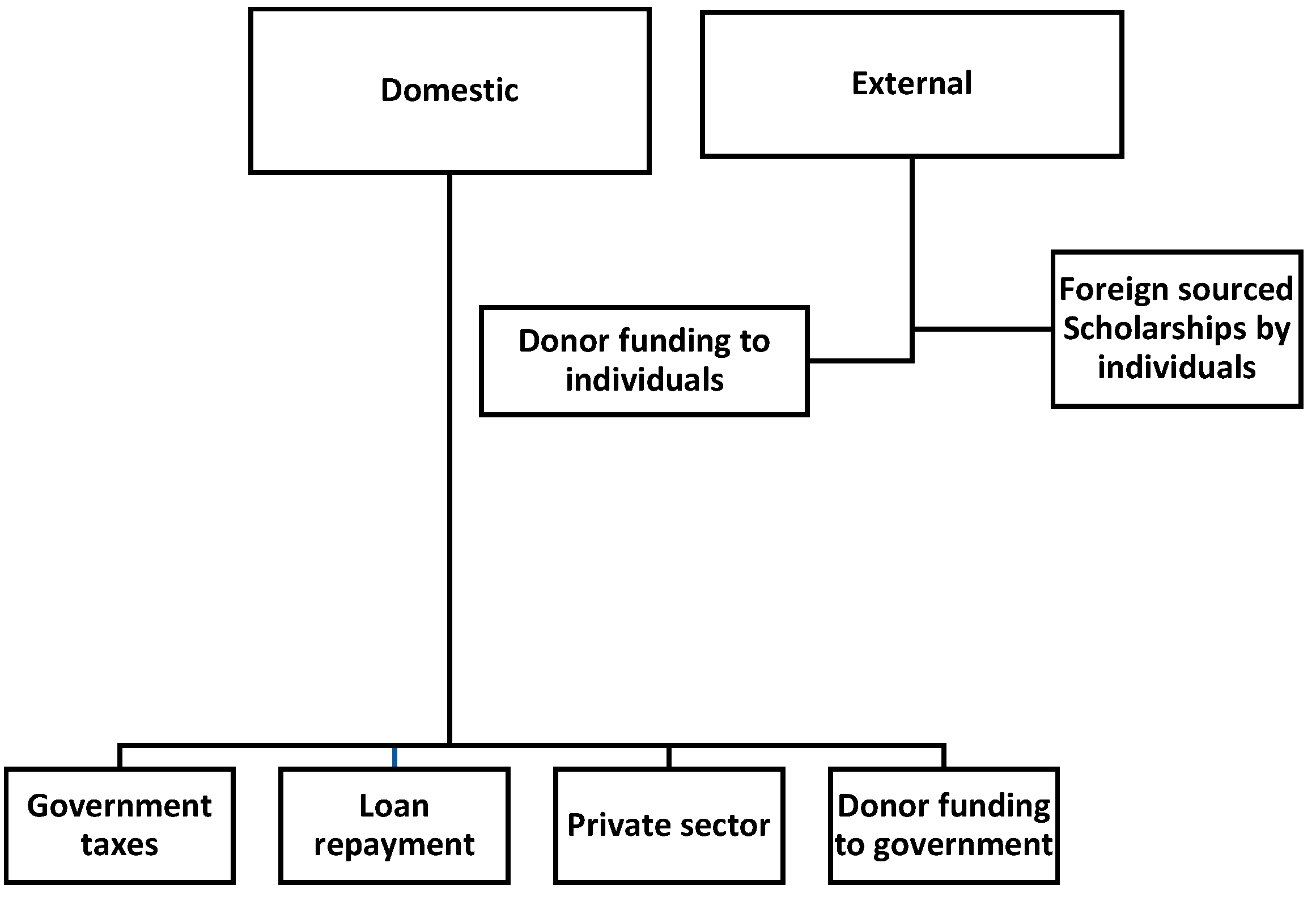

3.1.9. How Are the Schemes Funded and What Do They Pay for?

3.1.10. What Are the Benefits for the Individuals?

GBL1: So, Government decided: ‘ok, fine, uh, anybody who goes on government sponsorship, they will be given full salary irrespective of the number of years that you go for’.

PP1: Uh, you can’t be getting your full salary whilst you are not doing anything in terms of work. It wouldn’t be fair to those who are at work.

3.2. Understanding the Implementation and Implementers of Return-of-Service Schemes in the Three Countries (Process and Actors)

3.2.1. How Are the Service Needs Determined?

FZ1: So, that’s why we are guided by… HRDC, they call it top occupants’ fields.

DS1: After finalisation of the priority areas, we publish them for the people to know that these are the programmes that we will be taking out of the country and then when it’s time for applications, we issue a notice advert that, applications are now open for these particular programmes and these are the conditions and now you apply… our budget will determine how many students we take because of the issue of affordability. If we can only afford about 200, then we’ll take 200 if we can afford up to 400, then we’ll take 400.

DS3: …within that limit, they do not come to us and prescribe how many we can have, but they will say: ‘Ministry of Health I only have this amount of money… so, what are your priorities?’, and then we would stipulate our priorities… then we would say within the one that allows us to recruit new people, our priorities will be doctors, nurses and what…

3.2.2. Application Process

DS1: Our Facebook page is more effective. We also use the state radio…and any other platforms that are available. For example, I just give it to you through WhatsApp, you issue it to the, uh, WhatsApp groups… We also take it to the Ministry website. So, it’s actually more or less like word of mouth…and we also put it on our notices.

3.2.3. How Are Eligible Beneficiaries Selected from Applicants?

FZ1: It will be a Board where somebody comes and present to say we have these 300 students looking for sponsorship and then we look at the applications and then we make recommendations as a Board.

DS1: …we first establish a team that’s going to work through all the applications from the start to finish. … then the selection is taken. We have a Council that… that oversees, the whole NMDS [National Manpower Development Secretariat] operations. So…, after capturing of the candidates they are then forwarded to, our Council… and the Council will make the… decision on the selected and who is not. From the Council then it will go to our Minister, but our Minister is just to show him that ok, these are the students who have been selected, these are those that have not been selected. Then the Minister, when he satisfied with what he has gotten then he will approve.

3.2.4. How Are Beneficiaries Monitored during Their Studies?

DS1: We don’t have such a system, that is why people are defaulting.

FZ1: We have Education outages who actually are staff members from the Department who are stationed in missions outside the country. So, their job is to monitor the students’ performance and welfare during their course of studies. But once the students have completed and they are back in Botswana, no, we don’t really make contact with them at all. Unless they come back to us for another sponsorship.

3.2.5. How Are Beneficiaries Recruited into Employment?

DS1: So, the Ministry of Health will then place them, I don’t really know how that happens, but they register with the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Health will place them according to the vacancies, I think.

DS3: …what they normally do, is that they would apply to the Ministry of Health, they introduce themselves like, I am so, and so who is qualified recently, qualified somewhere, I am completing on this date. So, I am applying for a job…

3.2.6. How Are Beneficiaries Monitored after the Completion of Their Studies?

3.2.7. Who Are the Actors Involved in the Success of These Schemes?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boniol, M.; Kunjumen, T.; Nair, T.S.; Siyam, A.; Campbell, J.; Diallo, K. The global health workforce stock and distribution in 2020 and 2030: A threat to equity and ‘universal’ health coverage? BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.; Scheffler, R.M.; Nyoni, J.; Boerma, T. A comprehensive health labour market framework for universal health coverage. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 892–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, C.P.; Khumalo, T.; Nkwanyana, N.; Mathunjwa-Dlamini, T.R.; Macera, L.; Nsibandze, B.S.; Kaplan, L.; Stuart-Shor, E.M. Developing and Implementing the Family Nurse Practitioner Role in Eswatini: Implications for Education, Practice, and Policy. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamani, J.A.; Zurn, P.; Pitso, P.; Mothebe, M.; Moalosi, N.; Malieane, T.; Izquierdo, J.P.B.; Zbelo, M.G.; Hlabana, A.M.; Humuza, J.; et al. Health workforce supply, needs and financial feasibility in Lesotho: A labour market analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, M.L.; Peersman, W.; Daou, P.; Diakité, C.; Bajunirwe, F.; Mubangizi, V.; Mahmoud, E.H.; Moosa, S.; Phaladze, N.; Nkomazana, O.; et al. Human resources for primary health care in sub-Saharan Africa: Progress or stagnation? Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbe, J.H.; Legum, C.; Guy, J.J. Map of Lesotho and Geographical Facts; Encyclopedia Britannica: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Lesotho (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Masson, J.R. Eswatini; Encyclopedia Britannica: Mbabane, Eswatini, 2023; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Eswatini (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Parsons, N. Botswana; Encyclopedia Britannica: Gaborone, Botswana, 2023; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Botswana (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H. Our World in Data: HIV/AIDS. 2019. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- The World Bank. Incidence of Tuberculosis (per 100,000 People); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- The World Bank. World Data; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy On Human Resources For Health: Workforce 2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mabunda, S.A.; Durbach, A.; Chitha, W.W.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R. Are return-of-service bursaries an effective investment to build health workforce capacity? A qualitative study of key South African policymakers. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Human Development Index (HDI) by Country 2022; New York, NY, USA, 2022. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/hdi-by-country (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Worldometers. Life-Expectancy; Dadax: Shanghai, China, 2022; Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/life-expectancy/ (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Nkomazana, O.; Peersman, W.; Willcox, M.; Mash, R.; Phaladze, N. Human resources for health in Botswana: The results of in-country database and reports analysis. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2014, 6, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Botswana Ministry of Health. Botswana Human Resources Strategic Plan: 2007–2016; Republic of Botswana Ministry of Health: Gaborone, Botswana, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Human Resources Development & Strategic Plan: 2005–2025; Kingdom of Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare: Maseru, Lesotho, 2004; Available online: https://www.socialserviceworkforce.org/system/files/resource/files/Kingdom%20of%20Lesotho%20HR%20Development%20and%20Strategic%20Plan.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Kingdom of Swaziland Ministry of Health. Human Resources for Health Strategic Plan: 2012–2017; Kingdom of Swaziland Ministry of Health: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2012; Available online: https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/swaziland/policy_for_human_resources_for_health.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Mabunda, S.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R.; Durbach, A. Evaluation of the alignment of policies and practices for state-sponsored educational initiatives for sustainable health workforce solutions in selected Southern African countries: A protocol, multimethods study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabunda, S.; Angell, B.; Yakubu, K.; Durbach, A.; Joshi, R. Reformulation and strengthening of return-of-service (ROS) schemes could change the narrative on global health workforce distribution and shortages in sub-Saharan Africa. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitio-Kgokgwe, O.; Gauld, R.D.; Hill, P.C.; Barnett, P. Analysing the Stewardship Function in Botswana’s Health System: Reflecting on the Past, Looking to the Future. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2016, 5, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, J.; Christmals, C.D.; Asamani, J.A.; Illou, M.M.A.; Okoroafor, S.; Nabyonga-Orem, J.; Ahmat, A. The process of developing health workforce strategic plans in Africa: A document analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, J.; Gbary, A.; Awases, M.; Ndecki, P.; Chatora, R. Policies and Plans for Human. Resources for Health: Guidelines for Countries in the WHO African Region; 9290231041XXXX; WHO Press: Brazaville, Congo, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J.; MacLeod, A.; Ellaway, R.H. CARDA: Guiding document analyses in health professions education research. Med. Educ. 2022, 57, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walt, G.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Botswana. General Orders Covering the Conditions of Service of the Public Service of the Republic of Botswana; Government of Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 1996; Available online: https://books.google.com.au/books?id=UXtSzgEACAAJ (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Government of Botswana. Public Service Act (Act No. 30 of 2008-Cap. 26:01): S.I. 19, 2010; Government of Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 2010; Available online: https://uclgafrica-alga.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Public-service-act-Botswana.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Khumalo, N.S. An Evaluation of the “In-service Training Policy” in Swaziland with Specific Reference to the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Trade and the Ministry of Health. Master’s Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Berea, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Lesotho. National Manpower Development Council Act (Act No. 8 of 1978); Authority of the Prime Minister: Maseru, Lesotho, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Lesotho. Loan Bursary Fund Regulations: Supplement No. 1 to Gazette No. 29 of 11th August, 1978 (Legal Notice No. 20 of 1978); Authority of the Prime Minister: Maseru, Lesotho, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Swaziland. The In-Service Training Policy of 2000; Ministry of Public Service: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Lesotho. National Strategic Development Plan 2012/13-2016/17: Growth and Development Strategic Framework; Government of Lesotho: Maseru, Lesotho, 2012; Available online: https://hivstar.lshtm.ac.uk/files/2017/11/national-strategic-development-plan-201213-201617-LESOTHO.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Government of the Kingdom of Eswatini. The Kingdom of Eswatini Strategic Road Map: 2019–2022; Government of the Kingdom of Eswatini: Lobamba, Eswatini; Available online: https://www.cabri-sbo.org/uploads/bia/Swaziland_2019_Planning_External_NationalPlan_NatGov_COMESASADC_English.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland. The Swaziland Poverty Reduction Strategy and Action Plan (PRSAP); Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2007; Available online: https://www.tralac.org/files/2012/12/Final-Poverty-Reduction-Strategy-and-Action-Plan-for-Swaziland.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Government of Botswana. Guidelines Governing Award of Sponsorship; Ministry of Education, Department of Tertiary Education Financing: Goborone, Botswana, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mthethwa, K.F. Training and Localisation Policy: A Case Study of Swaziland. Master’s Thesis, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The Immigration Act, 1964. 1965. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/86516/97729/F480334340/SWZ86516.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Swaziland Ministry of Education and Training. The Swaziland Education and Training Sector Policy; Swaziland Ministry of Education and Training: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2011; Available online: https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/swazilandeducationsectorpolicy2011.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Government of Swaziland. The National Development Strategy (NDS); Government of Swaziland: Mbabane, Swaziland, 2014; p. 39. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/sz/UNDP_SZ_Poverty_National_Development_Strategy.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Government of Botswana. Vision. 2016: A Long Term Vision for Botswana; Government of Botswana: Gaborone, Botswana, 1999; p. 66. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/BOT181142.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Barnighausen, T.; Bloom, D.E. Financial incentives for return of service in underserved areas: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnighausen, T.; Bloom, D.E. “Conditional scholarships” for HIV/AIDS health workers: Educating and retaining the workforce to provide antiretroviral treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, C. Doctor shortages: Unpacking the ‘Cuban solution’. S. Afr. Med. J. 2013, 103, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, C. An inside view: A Cuban trainee’s journey. S. Afr. Med. J. 2013, 103, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, E.; Reid, S. Do South African medical students of rural origin return to rural practice? S. Afr. Med. J. 2003, 93, 789–793. [Google Scholar]

- Donda, B.M.; Hift, R.J.; Singaram, V.S. Assimilating South African medical students trained in Cuba into the South African medical education system: Reflections from an identity perspective. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goma, F.M.; Murphy, G.T.; MacKenzie, A.; Libetwa, M.; Nzala, S.H.; Mbwili-Muleya, C.; Rigby, J.; Gough, A. Evaluation of recruitment and retention strategies for health workers in rural Zambia. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12 (Suppl. S1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, J.; George, G.; Mwamba, S.; Ingombe, L.; Mutinta, G. An evaluation of the effectiveness of the Zambian Health Worker Retention Scheme (ZHWRS) for rural areas. Afr. Health Sci. 2013, 13, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobler, L.; Marais, B.J.; Mabunda, S. Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd005314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeville, K.L.; Hanson, K.; Muula, A.S.; Dzowela, T.; Ulaya, G.; Lagarde, M. Specialty training for the retention of Malawian doctors: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeville, K.L.; Ulaya, G.; Lagarde, M.; Muula, A.S.; Dzowela, T.; Hanson, K. The use of specialty training to retain doctors in Malawi: A discrete choice experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, S.M.; Mathews, M. Canadian return-for-service bursary programs for medical trainees. Healthc. Policy 2012, 7, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, H.K.; Diamond, J.J.; Markham, F.W.; Hazelwood, C.E. A program to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas: Impact after 22 years. JAMA 1999, 281, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempowski, I.P. Effectiveness of financial incentives in exchange for rural and underserviced area return-of-service commitments: Systematic review of the literature. Can. J. Rural. Med. 2004, 9, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, M.; Heath, S.L.; Neufeld, S.M.; Samarasena, A. Evaluation of physician return-for-service agreements in Newfoundland and Labrador. Heal. Policy 2013, 8, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, A.P.; Liyanage, I.K.; De Silva, S.T.G.R.; Jayawardana, M.B.; Liyanage, C.K.; Karunathilake, I.M. Migration of Sri Lankan medical specialists. Hum. Resour. Health 2013, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, E.; Brown, T.M. A return to the social justice spirit of Alma-Ata. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1096–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, E.; Brown, T.M. Declaration of ALMA-ATA. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1094–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, O.A.; Ofili, A.N. Strengthening intersectoral collaboration for primary health care in developing countries: Can the health sector play broader roles? J. Environ. Public. Health 2010, 2010, 272896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, V.B.; Ahaisibwe, B.; Malewezi, B.; Ngoma, D.; Daoust, P.; Stuart-Shor, E.; Mannino, C.A.; Day, D.; Foradori, L.; Sayeed, S.A. Partnering to Build Human Resources for Health Capacity in Africa: A Descriptive Review of the Global Health Service Partnership’s Innovative Model for Health Professional Education and Training From 2013–2018. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K. Collaborative governance of public health in low- and middle-income countries: Lessons from research in public administration. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. Policy Problems and Policy Design; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, H.K. Estimating the percentage of primary care rural physicians produced by regular and special admissions policies. J. Med. Educ. 1986, 61, 598–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, H.K. The effects of a selective medical school admissions policy on increasing the number of family physicians in rural and physician shortage areas. Res. Med. Educ. 1987, 26, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, H.K. Evaluation of a selective medical school admissions policy to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, H.K. The role of the medical school admission process in the production of generalist physicians. Acad. Med. 1999, 74, S39–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Botswana | Eswatini | Lesotho |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population, 2022 | 2,441,162 | 1,184,817 | 2,175,699 |

| Population density (per square kilometre), 2022 | 4.2 | 68.2 | 71.7 |

| GDP per capita (USD, Billions), 2021 | 7347.6 | 4214.9 | 1166.5 |

| Human development index rank, 2022 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Income level, 2020 | Upper-middle | Lower-middle | Lower-middle |

| Doctor density (per 10,000 population), 2018 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 4.7 |

| Nursing and midwifery personnel density (per 10,000 population), 2018 | 37.7 | 41.4 | 32.6 |

| Life expectancy (years), 2020 | 69.9 | 61.1 | 55.7 |

| Under-5 mortality rate (per 1000 live births), 2020 | 44.8 | 46.6 | 89.5 |

| HIV/AIDS prevalence (%), 2019 | 20.1 | 27.7 | 24.8 |

| Tuberculosis incidence (per 100,000), 2020 | 236 | 650 | 319 |

| Pre-Service Programme | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Botswana | Eswatini | Lesotho |

| Administering Ministry/Agency | Education | Labour | NMDS |

| Earliest policy found | 1995 | 1977 | 1978 |

| Countries of study |

|

|

|

| In-Service Programme | |||

| Administering Ministry/Agency | Health | Public Service | NMDS |

| Earliest policy found | 1996 | 2000 | 1978 |

| Countries of study |

|

|

|

| Characteristic | Botswana | Eswatini | Lesotho | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Health | Labour | Public Service | National Manpower Development Secretariat | |

| Suitability criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

| Beneficiary obligations |

|

|

|

|

|

| Service period | Duration funded ×1 |

| Duration funded ×2 | Duration funded +1 | Duration funded ×2 (minimum service period = 3 years if funded for 1 year) |

| Repayment of funds | None for health science beneficiaries (100% repayment for non-health sciences beneficiaries) | None |

| None |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mabunda, S.A.; Durbach, A.; Chitha, W.W.; Moaletsane, O.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R. How Were Return-of-Service Schemes Developed and Implemented in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho? Healthcare 2023, 11, 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101512

Mabunda SA, Durbach A, Chitha WW, Moaletsane O, Angell B, Joshi R. How Were Return-of-Service Schemes Developed and Implemented in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho? Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101512

Chicago/Turabian StyleMabunda, Sikhumbuzo A., Andrea Durbach, Wezile W. Chitha, Oduetse Moaletsane, Blake Angell, and Rohina Joshi. 2023. "How Were Return-of-Service Schemes Developed and Implemented in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho?" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101512