Physician’s Knowledge and Attitudes on Antibiotic Prescribing and Resistance: A Cross-Sectional Study from Hail Region of Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Procedure

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Questionnaire Validation

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

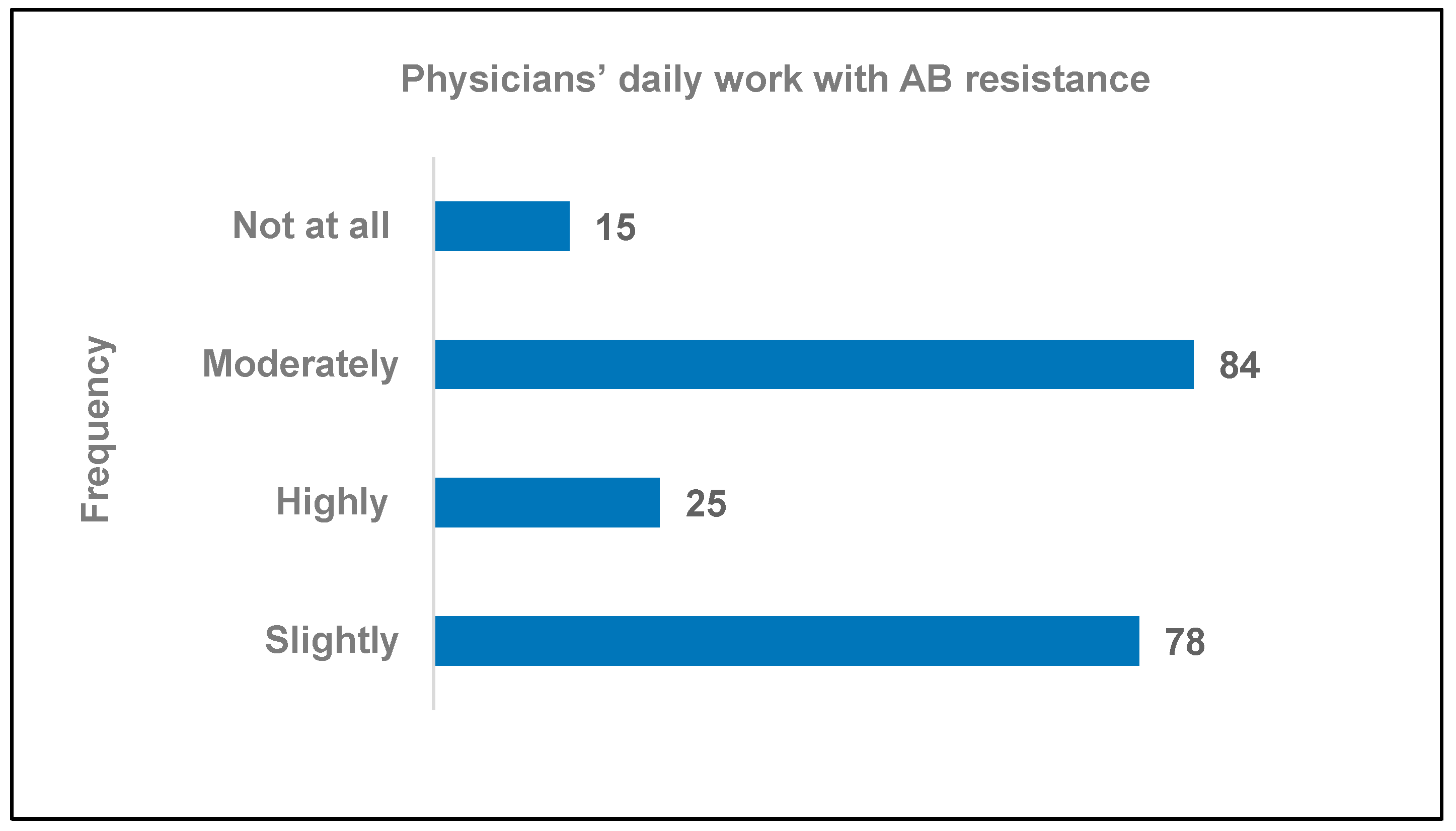

3.2. AB Resistance Experience in Daily Work

3.3. Views on the Impact of AB Prescribing Behavior on the Development of AB Resistance

3.4. AB Prescribing Behavior

3.5. Communication with Patients Regarding AB Resistance

3.6. Prescribing Practices

3.7. Delayed AB Prescribing Strategy and Practice Guidelines

3.8. Reasons for Avoiding Discussing AB Resistance with Patients

3.9. Reasons for ABs Being Prescribed without Clear Clinical Indications of Disease

3.10. Views on Evidence-Based Therapy Guidelines for AB Prescription

3.11. Sources Consulted to Obtain Current/New Information on AB Therapy

3.12. Additional Information Sources Considered Helpful for Reducing AB Resistance

3.13. Effects of Different Variables on Physicians’ Responses: A Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The Evolving Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance: Options for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, I.N.; Lamikanra, A.; Edelman, R. Socioeconomic and Behavioral Factors Leading to Acquired Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics in Developing Countries. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999, 5, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameh, M.; Green, J.; Norris, P. Over-the-counter sales of antibiotics from community pharmacies in Abu Dhabi. Pharm. World Sci. 2010, 32, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, A.; Eltayeb, I.; Matowe, L.; Thalib, L. Self-medication with antibiotics and antimalarials in the community of Khartoum State, Sudan. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 8, 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Belkina, T.; Al Warafi, A.; Eltom, E.H.; Tadjieva, N.; Kubena, A.; Vlcek, J. Antibiotic use and knowledge in the community of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Uzbekistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 8, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hazmi, A.M.; Arafa, A.; Sheerah, H.; Alshehri, K.S.; Alekrish, K.A.; Aleisa, K.A.; Jammah, A.A.; Alamri, N.A. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Nonprescription Antibiotic Use among Individuals Presenting to One Hospital in Saudi Arabia after the 2018 Executive Regulations of Health Practice Law: A Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chem, E.D.; Anong, D.N.; Akoachere, J.-F.K.T. Prescribing patterns and associated factors of antibiotic prescription in primary health care facilities of Kumbo East and Kumbo West Health Districts, North West Cameroon. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.T.; Roque, F.; Falcão, A.; Figueiras, A.; Herdeiro, M.T. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altiner, A.; Wilm, S.; Däubener, W.; Bormann, C.; Pentzek, M.; Abholz, H.-H.; Scherer, M. Sputum colour for diagnosis of a bacterial infection in patients with acute cough. Scand. J. Prim. Heal. Care 2009, 27, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Fatima, N.; Alvi, A. Epidemiology and pattern of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori: Scenario from Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Faiz, A. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in tertiary care hospitals of Makkah and Jeddah. Ann. Saudi Med. 2016, 36, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baadani, A.M.; Baig, K.; Alfahad, W.A.; Aldalbahi, S.; Omrani, A.S. Physicians’ knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes toward antimicrobial prescribing in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Nafisah, S.; Bin Nafesa, S.; Alamery, A.H.; Alhumaid, M.A.; AlMuhaidib, H.M.; Al-Eidan, F.A. Over-the-counter antibiotics in Saudi Arabia, an urgent call for policy makers. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Abahussain, N.; Taha, A.Z. Knowledge and attitudes of female school students on medications in eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shibani, N.; Hamed, A.; Labban, N.; Al-Kattan, R.; Al-Otaibi, H.; Alfadda, S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of antibiotic use and misuse among adults in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key Health Indicators—2010 Health Indicators. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/Indicator/Pages/Indicator-2012-01-10-0001.aspx (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Raosoft, Inc. Sample Size Calculator. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis: Part 1: Causes and Threats. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, A.; Song, X.; Richards, A.; Sinkowitz-Cochran, R.; Cardo, D.; Rand, C. A Survey of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs of House Staff Physicians from Various Specialties Concerning Antimicrobial Use and Resistance. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakolkaran, N.; Shetty, A.V.; D’Souza, N.D.; Shetty, A.K. Antibiotic prescribing knowledge, attitudes, and practice among physicians in teaching hospitals in South India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2017, 6, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamany, S.; Schulkin, J.; E Rose, C.; E Riley, L.; E Besser, R. Knowledge, attitudes, and reported practices among obstetrician-gynecologists in the USA regarding antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 13, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Shen, J.; Bo, T.; Peng, L.; Xu, H.; Nasser, M.I.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhao, M. Cutting Edge: Probiotics and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Immunomodulation. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Llamocca, L.P.; García, K.; Jiménez, A.; Samalvides, F.; Gotuzzo, E.; Jacobs, J. Knowledge, attitudes and practice survey about antimicrobial resistance and prescribing among physicians in a hospital setting in Lima, Peru. BMC Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulcini, C.; Williams, F.; Molinari, N.; Davey, P.; Nathwani, D. Junior doctors’ knowledge and perceptions of antibiotic resistance and prescribing: A survey in France and Scotland. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Ikram, M.N.; Ijaz-Ul-Haq, M.; Noor, I.; Rasool, M.F.; Ishaq, H.M.; Rehman, A.U.; Hasan, S.S.; Fang, Y. Perception, Attitude, and Confidence of Physicians About Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Prescribing Among COVID-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study from Punjab, Pakistan. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellit, T.H.; Owens, R.C.; McGowan, J.E.; Gerding, D.N.; Weinstein, R.A.; Burke, J.P.; Huskins, W.C.; Paterson, D.L.; Fishman, N.O.; Carpenter, C.F.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for Developing an Institutional Program to Enhance Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, S.R. Revenge of the killer microbe. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 177, 895–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.C.; Fowler, T.; Watson, J.; Livermore, D.M.; Walker, D. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer: Infection and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 2013, 381, 1606–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, S.; Gonzales, R. The Context of Antibiotic Overuse. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.A.; Ali, M.S.; Anwar, S. Bacteria Causing Urinary Tract Infections and Its Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern at Tertiary Hospital in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.A.; Sadoma, H.H.M.; Mathew, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Malik, J.A.; Anwar, S. Retrospective Analysis of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Uropathogens Isolated from Pediatric Patients in Tertiary Hospital at Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step A. Content and Validity | Step B. Reliability Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Content Search | Content Validity | Pilot Study | |

Primary Stage

| Expert Review

| Cronbach’s Analysis Physicians (n = 10) Alpha value = 0.73 | Retest Analysis Physicians (n = 10) ICC value = 0.5 |

| Parameters | Total 221 (100%) | Age Groups | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–30 Years 19 (9.5%) | 31–40 Years 79 (39.3%) | 41–50 Years 66 (32.8%) | >50 Years 37 (18.4%) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 124 (61.7) | 10 (5.0) | 48 (23.9) | 38 (18.9) | 28 (13.9) | 0.238 |

| Female | 77 (38.3) | 9 (4.5) | 31 (15.4) | 28 (13.9) | 9 (4.5) | |

| Specialization | ||||||

| General practitioner | 70 (34.8) | 18 (9.0) | 34 (16.9) | 11 (5.5) | 7 (3.5) | <0.05 |

| Internal Medicine | 19 (9.5) | 0 | 13 (6.5) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 24 (11.9) | 0 | 6 (3.0) | 8 (4.0) | 10 (5.0) | |

| ENT | 10 (5.0) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | 6 (3.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Pulmonology | 12 (6.0) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Pediatrics | 14 (7.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (3.5) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Urology and Nephrology | 12 (6.0) | 0 | 6 (3.0) | 5 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Cardiology | 9 (4.5) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Psychiatry | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 | |

| Surgeon and General Surgery | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | |

| Plastic Surgery | 4 (2.0) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Anesthesiology | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 | |

| Dermatology | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Ophthalmology | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) | 0 | |

| Orthopedics | 6 (3.0) | 0 | 0 | 6 (3.0) | 0 | |

| Sector of Employment | ||||||

| General—Specialized Hospitals | 112 (56.3) | 15 (7.5) | 44 (22.1) | 31 (15.6) | 22 (11.1) | 0.187 |

| Govt Primary Care Centers | 32 (16.1) | 2 (1.0) | 13 (6.5) | 13 (6.5) | 4 (2.0) | |

| Private Hospitals/Clinics | 55 (27.6) | 1 (0.5) | 21 (10.6) | 21 (10.6) | 12 (6.0) | |

| Visits per Quarter (Three Months) to the Clinic | Frequency | Percent | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤100 | 27 | 13.36 | 2.25–16.3 |

| 101–300 | 46 | 23.10 | 5.12–24.7 |

| 301–500 | 50 | 25.10 | 5.78–31.3 |

| 501–800 | 38 | 19.10 | 0.84–19.7 |

| 801–1200 | 17 | 8.50 | 3.80–12.3 |

| 1201–1600 | 9 | 4.50 | 0.137–4.64 |

| >1600 | 12 | 6.00 | 2.34–7.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almansour, K.; Malik, J.A.; Rashid, I.; Ahmed, S.; Aroosa, M.; Alenezi, J.M.; Almatrafi, M.A.; Alshammari, A.A.; Khan, K.U.; Anwar, S. Physician’s Knowledge and Attitudes on Antibiotic Prescribing and Resistance: A Cross-Sectional Study from Hail Region of Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111576

Almansour K, Malik JA, Rashid I, Ahmed S, Aroosa M, Alenezi JM, Almatrafi MA, Alshammari AA, Khan KU, Anwar S. Physician’s Knowledge and Attitudes on Antibiotic Prescribing and Resistance: A Cross-Sectional Study from Hail Region of Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2023; 11(11):1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111576

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmansour, Khaled, Jonaid Ahmad Malik, Ishfaq Rashid, Sakeel Ahmed, Mir Aroosa, Jehad M. Alenezi, Mohammed A. Almatrafi, Abdulmajeed A. Alshammari, Kashif Ullah Khan, and Sirajudheen Anwar. 2023. "Physician’s Knowledge and Attitudes on Antibiotic Prescribing and Resistance: A Cross-Sectional Study from Hail Region of Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 11, no. 11: 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111576