The Effect of Music as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention on the Physiological, Psychological, and Social Response of Patients in an Intensive Care Unit

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Methods

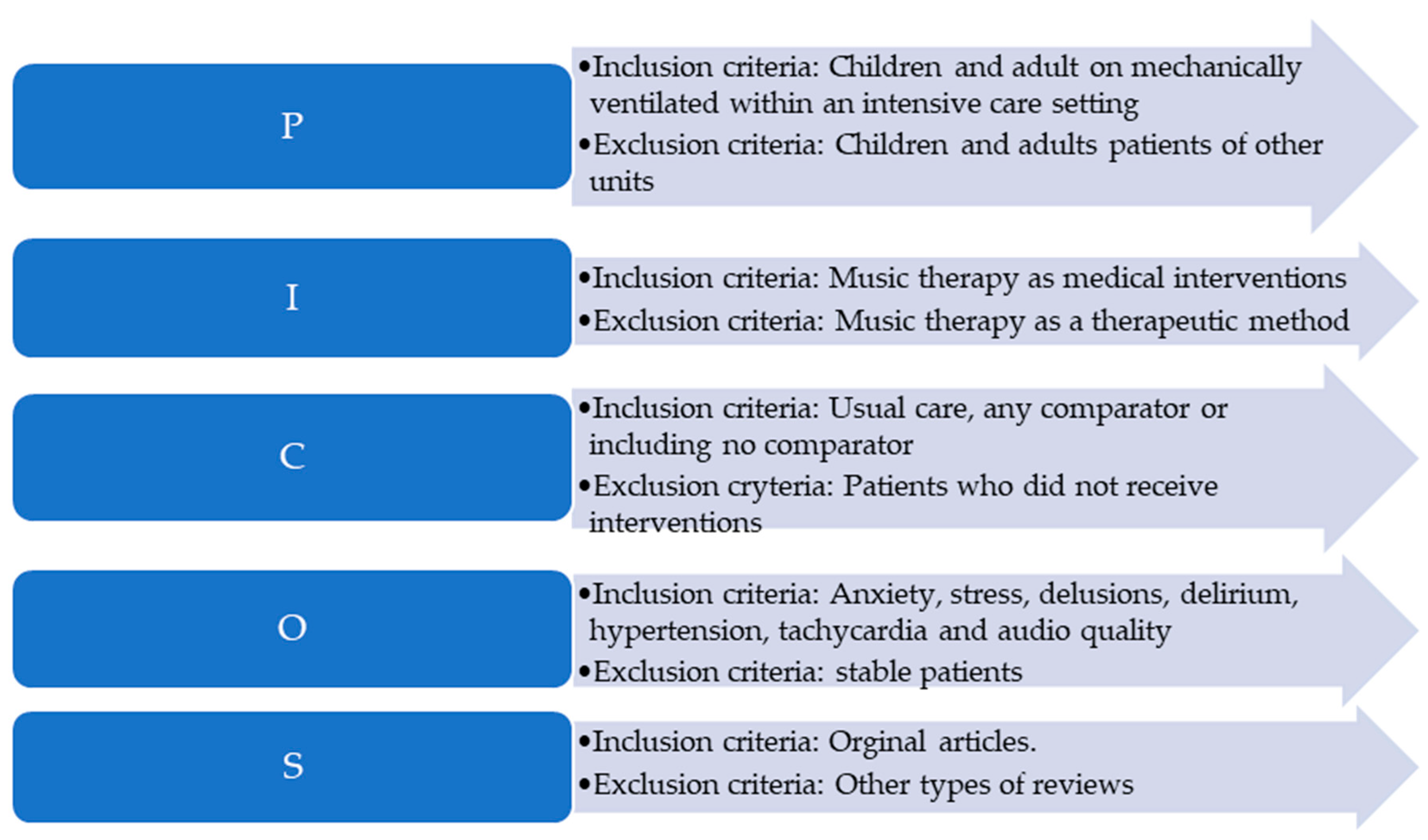

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Ethical Aspects

2.6. Assessment of the Study Quality of the Included Studies

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Selection of the Source of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.3. Types of Music Therapies

3.4. The Impact of Music on the Physiological, Psychological, and Social Responses of Patients in an Intensive Care Unit

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications for Nursing Practice

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMTA | The American Music Therapy Association |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| CAM-ICU | Confusion Assessment Method in Intensive Care Unit |

| CAM-ICU-7 | Confusion Assessment Method in Intensive Care Unit 7 |

| CG | Control Group |

| CPOT | Critical Care Pain Observation Tool |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| FAS | Facial Anxiety Scale |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| HT | Head Trauma |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LOC | Level of Consciousness |

| MAR | Music-Assisted Relaxation |

| MT | Music Therapy |

| NIV | Non-invasive ventilation |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| PDM | Patient-Directed Music |

| PDMI | Patient-Directed Music Intervention |

| PDMT | Patient-Direct Music Therapy |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| PTSD | The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| RASS | Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Gullick, J.G.; Kwan, X.X. Patient-directed music therapy reduces anxiety and sedation exposure in mechanically-ventilated patients: A research critique. Aust. Crit. Care 2015, 28, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahal, J.K.; Sharma, P.; Sulena Rawat, H.C.L. Effect of music therapy on ICU induced anxiety and physiological parameters among ICU patients: An experimental study in a tertiary care hospital in India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, A.J.; Leone, R.; Gollenberg, A.; Christopher, C.; Stanger, D.; Davis, T.M.; Anthony Meadows, A.; Zhang, Z.; Friesen, M.A. Impact of an Active Music Therapy Intervention on Intensive Care Patients. Am. J. Crit. Care 2019, 28, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DellaVolpe, J.D.; Huang, D.T. Is there a role for music in the ICU? Crit. Care 2015, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AMTA. About Music Therapy. Available online: https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/ (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Manchaster Music School. What Is Music Therapy? Available online: https://mcmusicschool.org/what-is-music-therapy/ (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Heiderscheit, A.; Johnson, K.; Chlan, L.L. Analysis of Preferred Music of Mechanically Ventilated Intensive Care Unit Patients Enrolled in a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Integr. Complement Med. 2022, 28, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.K.; Moore, M.L. Music intervention in the intensive care unit: A complementary therapy to improve patient outcomes. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2004, 7, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messika, J.; Kalfon, P.; Ricard, J.D. Adjuvant therapies in critical care: Music therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 1929–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Cadorin, L.; Testa, M.; Geri, T.; Colloca, L.; Rossettini, G. Contextual factors triggering placebo and nocebo effects in nursing practice: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1966–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.R.; Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Angst, M.S.; Dionne, R.; Freeman, R.; Hansson, P.; Haroutounian, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Attal, N.; et al. Patient phenotyping in clinical trials of chronic pain treatments: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain Rep. 2021, 6, e896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Ambrosi, E.; Stefani, F.; Zenere, B.A.; Saiani, L. The activities/tasks performed by health care aids in hospital settings: A mixed-methods study. Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2019, 38, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Longhini, J.; Danielis, M. To what extent Unfinished Nursing Care tools coincide with the discrete elements of The Fundamentals of Care Framework? A comparative analysis based on a systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 239–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappe, H.J. Role of music in intensive care medicine. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2012, 2, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- PRISMA. PRISMA-ScR-Fillable-Checklist. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA-ScR-Fillable-Checklist_11Sept2019.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 Methodology for JBI Umbrella Reviews; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Li, J.P.; Sit, J.W.; Chung, L.; Jiao, Z.Y.; Ma, W.G. Effects of music intervention on physiological stress response and anxiety level of mechanically ventilated patients in China: A randomised controlled trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyffert, S.; Moiz, S.; Coghlan, M.; Balozian, P.; Nasser, J.; Rached, E.A.; Jamil, Y.; Naqvi, K.; Rawlings, L.; Perkins, A.J.; et al. Decreasing delirium through music listening (DDM) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated older adults in the intensive care unit: A two-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial. Trials 2022, 23, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.H.; Xu, C.; Purpura, R.; Durrani, S.; Lindroth, H.; Wang, S.; Gao, S.; Heiderscheit, A.; Chlan, L.; Boustani, M.; et al. Decreasing Delirium through Music: A Randomized Pilot Trial. Am. J. Crit. Care 2020, 29, e31–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ettenberger, M.; Maya, R.; Salgado-Vasco, A.; Monsalve-Duarte, S.; Betancourt-Zapata, W.; Suarez-Cañon, N.; Prieto-Garces, S.; Marín-Sánchez, J.; Gómez-Ortega, V.; Valderrama, M. The Effect of Music Therapy on Perceived Pain, Mental Health, Vital Signs, and Medication Usage of Burn Patients Hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Study Protocol. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 714209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, N.; Shuford, R.; Yang, L.; Moriyama, B.; Frey, M.; Wilson, F.; Sundaramurthi, T.; Gori, D.; Mannes, A.; Ranucci, A.; et al. Music Listening Among Postoperative Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: A Randomized Controlled Trial with Mixed-Methods Analysis. Integr. Med. Insights 2017, 12, 1178633717716455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Hsu, M.Y.; Lai, C.L.; Sung, Y.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Lin, L.Y. Effects of Music Intervention on State Anxiety and Physiological Indices in Patients Undergoing Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2017, 19, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; Fleury, J.; McClain, D. Music intervention to prevent delirium among older patients admitted to a trauma intensive care unit and a trauma orthopaedic unit. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018, 47, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallı, Ö.E.; Yıldırım, Y.; Aykar, F.Ş.; Kahveci, F. The effect of music on delirium, pain, sedation and anxiety in patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022, 2, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlan, L.L.; Heiderscheit, A.; Skaar, D.J.; Neidecker, M.V. Economic Evaluation of a Patient-Directed Music Intervention for ICU Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilatory Support. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.; Chaboyer, W.; Schluter, P.; Foster, M.; Harris, D.; Teakle, R. The effect of music on discomfort experienced by intensive care unit patients during turning: A randomized cross-over study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 16, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiasson, A.; Linda Baldwin, A.; McLaughlin, C.; Cook, P.; Sethi, G. The effect of live spontaneous harp music on patients in the intensive care unit. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 428731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, S.G.; Watters, R.; Thomson-Smith, C. Impact of Therapeutic Music Listening on Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Pilot Study. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 55, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaharani, A.; Acharya, S.; Kumar, S.; Gadegone, A.; Raisinghani, N. The effect of music therapy in critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit of a tertiary care center. J. Datta Meghe Inst. Med. Sci. Univ. 2019, 14, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, V.L.; Colau, H.; Barcos-Munoz, F.; Rimensberger, P.C.; Polito, A. Parents’ Views with Music Therapy in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Children 2022, 9, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekefallah, L.; Namdar, P.; Azimian, J.; Dost Mohammadi, S.; Mafi, M. The effects of musical stimulation on the level of consciousness among patients with head trauma hospitalized in intensive care units: A randomized control trial. Complement Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 42, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, F.; Yahya, N.B.; Gambazza, S.; Binda, F.; Galazzi, A.; Ferrari, A.; Crespan, S.; Al-Atroushy, H.A.; Cantoni, B.M.; Laquintana, D.; et al. Use of Musical Intervention in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Developing Country: A Pilot Pre–Post Study. Children 2022, 9, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yao, Y.; Chen, J.; Xiong, G. The effect of music therapy on the anxiety, depression and sleep quality in intensive care unit patients: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e28846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.; Chen, B.; Wang, L.; Gong, J.; Wang, R. Non-pharmacological Treatment of Intensive Care Unit Delirium. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 8, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Chang, M.-Y.; Chow, L.-H.; Ma, W.-F. Effectiveness of Music-Based Intervention in Improving Uncomfortable Symptoms in ICU Patients: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyar, M.; Akın Korhan, E. The effect of music therapy on pain and anxiety in intensive care patients. Agri 2011, 23, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, M.I.; Cooke, M.; Macfarlane, B.; Aitken, L.M. Factors associated with anxiety in critically ill patients: A prospective observational cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 60, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schäfer, T.; Sedlmeier, P.; Städtler, C.; Huron, D. The psychological functions of music listening. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, C.S.; Teixeira, J.; Figueiredo, P.; Xavier, J.; Castro, S.L.; Brattico, E. Music and emotions in the brain: Familiarity matters. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettenberger, M.; Calderón Cifuentes, N.P. Intersections of the arts and art therapies in the humanization of care in hospitals: Experiences from the music therapy service of the University Hospital Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Colombia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1020116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golino et al., 2019 [3] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Heiderscheit et al., 2022 [7] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Messika et al., 2026 [9] | Y | Y | n/a | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Han et al., 2010 [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Seyffert et al., 2022 [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Khan et al., 2020 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Ettenberger et al., 2021 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Ames et al., 2017 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | U |

| Lee et al., 2016 [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Johnson et al., 2018 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Dallı et al., 2022 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Chlan et al., 2019 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Cooke et al., 2010 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Chiasson et al., 2013 [28] | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Browning et al., 2020 [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jawaharani et al., 2020 [30] | Y | n/a | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Cousin et al., 2022 [31] | Y | n/a | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Yekefallah et al., 2021 [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | n/a | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Author and Date | Aim | Sample | Materials and Methods | Results | Implication for Nursing Practice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Group | Control Group (CG) | |||||

| Golino et al., 2019 [3] | Impact of an active music therapy intervention on intensive care patients | Adult patients |

| After the intervention, differences were found in the following vital functions: respiratory rate, heart rate, pain, and anxiety levels | Music therapy can be a form of non-pharmacological nursing intervention. It responds to the patient’s individual needs without posing risks to the patient | |

| 52 | X | |||||

| Seyffert et al., 2022 [19] | Decreasing delirium through music listening (DDM) in critically ill, mechanically ventilated older adults in the intensive care unit: a two-arm, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial | 160 mechanically ventilated adults |

| Decreases in heart rate and blood pressure | Music listening has been shown to activate areas of the brain involved with memory, cognitive function, and emotion | |

| 80 | 80 | |||||

| Khan et al., 2020 [20] | Decreasing delirium through music | 52 patients on mechanical ventilation |

|

| The use of music intervention in the intensive care unit is associated with reduced patient anxiety and, thus, less frequent use of sedative drugs. However, it can pose some logistical challenges in a nurse’s work | |

| Ettenberger et al., 2021 [21] | The effect of music therapy on perceived pain, mental health, vital signs, and medication usage of burn patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit | Adult burn patients from an ICU |

|

| The mechanisms of live and paired music can affect pain perception in adult burn patients | |

| Ames et al., 2017 [22] | Music listening among postoperative patients in the intensive care unit | 41 surgical patients from an ICU |

| The study found no significant effect on opioid use. The NRS score was found to be lower in the intervention group, and patients’ well-being also improved | Music therapy can be an additional intervention used by nurses for medical treatment, which has no side effects on the patient and can have a positive impact on pain sensations | |

| 20 | 21 | |||||

| Lee et al., 2016 [23] | Effects of music intervention on state anxiety and physiological indices in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit | 85 patients admitted to the ICU |

| After adjusting for demographics, an analysis of covariance showed that the music group had significantly better scores for all post-test measures and pre-post differences (except for diastolic blood pressure) | A 30 min intervention can already produce beneficial effects for the patient, and due to its low cost and ease of application, it can be used by nurses to reduce patient anxiety. Before and after the intervention, the nurse should monitor the patient’s condition | |

| 41 | 44 | |||||

| Johnson et al., 2018 [24] | Music intervention to prevent delirium among older patients admitted to a trauma intensive care unit and a trauma orthopedic unit | 40 patients aged >55 and older |

| Statistically significant differences in heart rate pre-/post-music listening | No data | |

| 20 | 20 | |||||

| Dallı et al., 2022 [25] | The effect of music on delirium, pain, sedation, and anxiety in patients receiving mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit | 36 patients |

| Significant decreases were found in the severity of delirium and pain and the level of sedation and anxiety | Musical intervention can be used as a nursing intervention to control delirium, pain, the need for sedation, and anxiety in intensive care patients | |

| 12 | 12 | |||||

| Chlan et al., 2019 [26] | Economic evaluation of a patient-directed music intervention for ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilatory support | 373 adult ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure |

| Savings in intensive care unit costs demonstrated; reduction in the costs of sedating drug requirements | Patient-directed music intervention is cost-effective for reducing anxiety in mechanically ventilated ICU patients | |

| Cooke et al., 2010 [27] | To identify the effect of music on discomfort experienced by ICU patients during the turning procedure | 17 postoperative patients |

| No differences between study and control groups | No data | |

| 10 | 7 | |||||

| Chiasson et al., 2013 [28] | To investigate the effect of live harp music on individual patients | 100 patients from the academic ICU |

| No significant difference between the study and control group in physiological parameters | No data | |

| 50 | 50 | |||||

| Browning et al., 2020 [29] | To explore the association between therapeutic music listening as a nursing intervention for patients in the ICU and the proportion of time the patients were considered to have delirium | 6 patients on mechanical ventilation |

| The study group spent more time alert and calm than agitated. The study group also experienced less proportion of time with documented ICU delirium than the CG did | Therapeutic music listening may be used as one of the nursing interventions. It requires no additional training for staff | |

| 3 | 3 | |||||

| Jawaharani et al., 2020 [30] | To study the effect of music therapy as an adjunct | 120 critically ill patients from an ICU |

| Better scores for the Glasgow Coma Scale, heart rate, blood pressure, and the Hamilton Anxiety Scale in the study group | No data | |

| 60 | 60 | |||||

| Cousin et al., 2022 [31] | To examine the perception of MT by children’s parents | Parents of children from a pediatric ICU 19 X |

| Parents thought that MT helped their child during hospitalization. | Music therapy intervention may be an alternative way to support children’s and parents’ physical well-being | |

| Yekefallah et al., 2021 [32] | The effects of musical stimulation on the level of consciousness among patients with head trauma hospitalized in intensive care units | 54 patients with HT |

|

| Music therapy can be used as a simple and non-expensive intervention to improve the clinical conditions of patients | |

| 27 | 27 | |||||

| Heiderscheit et al., 2022 [7] | Analysis of peferred music of mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients enrolled | 126 mechanically ventilated patients |

| The effectiveness of the intervention is influenced by the choice of music | Music therapy can be used as a simple and non-expensive intervention to improve the clinical conditions of patients | |

| Messika et al., 2016 [9] | Effect of a musical intervention on tolerance and efficacy of non-invasive ventilation in the ICU | 99 adult patients (≥18 years of age) |

| Non-pharmacological therapy that can affect patient perceived stress in an intensive care unit | ||

| 33 | 33 | |||||

| Han et al., 2010 [18] | Effects of music intervention on physiological stress response and anxiety level of mechanically ventilated patients in China | 137 mechanically ventilated patients in an ICU |

| Significant reduction in physiological stress response and an increase in heart rate and respiratory rate in the music-listening group; reduction in anxiety in the music-listening and headphones group but not in the control group | Music can be a non-pharmacological intervention and supplement in the nursing care of mechanically ventilated patients | |

| Intervention group n = 44 Placebo group n = 44 | 49 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorek, M.; Bąk, D.; Kwiecień-Jaguś, K.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. The Effect of Music as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention on the Physiological, Psychological, and Social Response of Patients in an Intensive Care Unit. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121687

Lorek M, Bąk D, Kwiecień-Jaguś K, Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W. The Effect of Music as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention on the Physiological, Psychological, and Social Response of Patients in an Intensive Care Unit. Healthcare. 2023; 11(12):1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121687

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorek, Magdalena, Dominika Bąk, Katarzyna Kwiecień-Jaguś, and Wioletta Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska. 2023. "The Effect of Music as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention on the Physiological, Psychological, and Social Response of Patients in an Intensive Care Unit" Healthcare 11, no. 12: 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121687

APA StyleLorek, M., Bąk, D., Kwiecień-Jaguś, K., & Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. (2023). The Effect of Music as a Non-Pharmacological Intervention on the Physiological, Psychological, and Social Response of Patients in an Intensive Care Unit. Healthcare, 11(12), 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121687