Is Rejection, Parental Abandonment or Neglect a Trigger for Higher Perceived Shame and Guilt in Adolescents?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Child Abandonment Concept and Its Consequences

3. The Association of Shame or Guilt with Parental Abandonment

4. Shame and Guilt in Adolescents

5. Methodology

5.1. The Present Study

5.2. Procedure

5.3. Hypotheses

5.4. Participants

5.5. Instruments

5.6. Results

5.6.1. Correlation Matrix

5.6.2. Descriptive Statistics

5.6.3. Hypotheses Testing

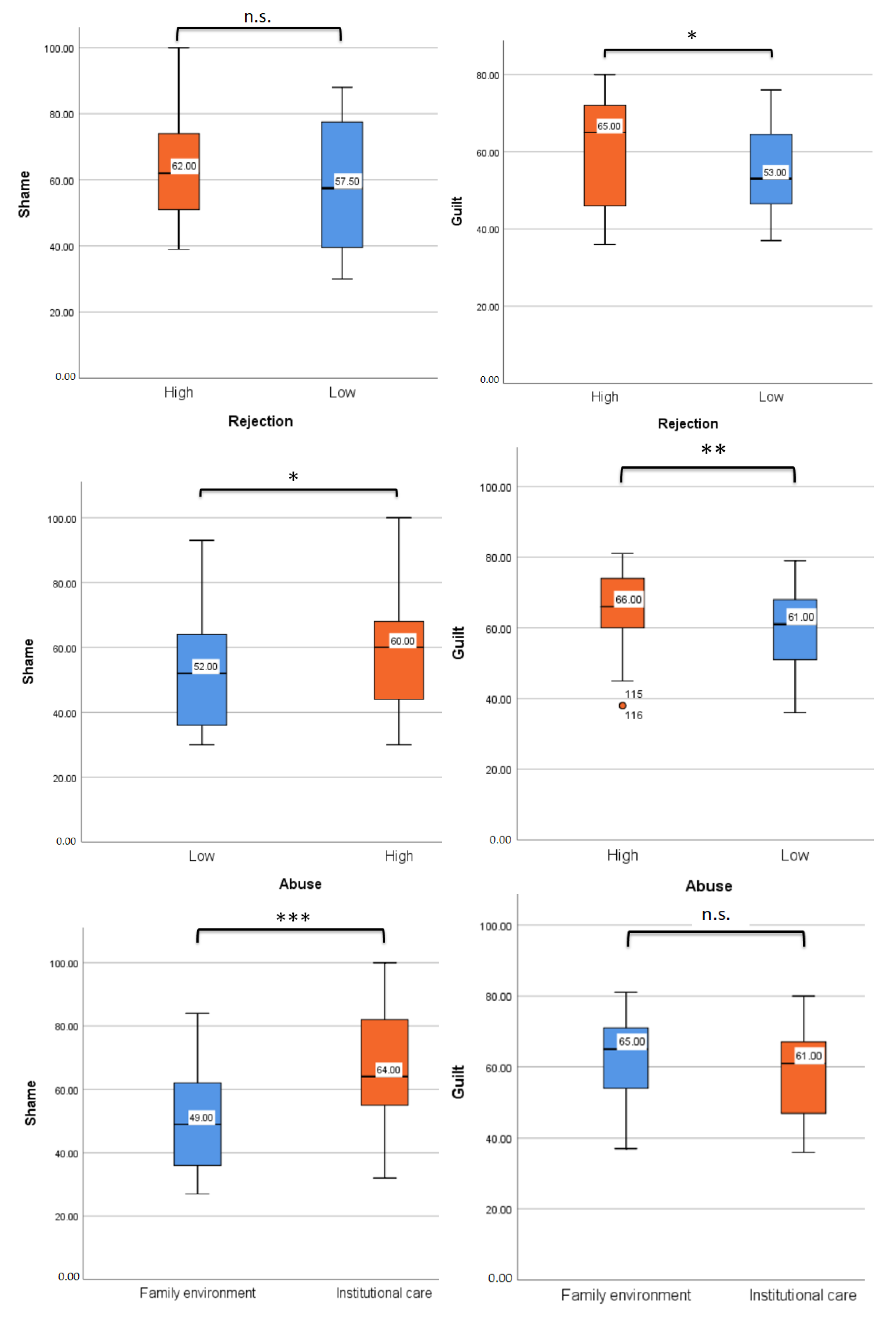

| Hypotheses | High Rejection | Low Rejection | t-Test | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (H1) ‘Children and teenagers with higher levels of parental rejection will report stronger feelings of shame than those with lower levels of rejection.’ | N = 38 | N = 32 | 1.580 | 68.0 | 0.119 |

| M = 65.1 | M = 58.0 | ||||

| SD = 17.4 | SD = 20.1 | ||||

| Mdn. = 62.0 | Mdn. = 57.5 | ||||

| SE = 2.830 | SE = 3.567 | ||||

| High rejection | Low rejection | ||||

| (H2) ‘Children and teenagers with higher levels of parental rejection will report stronger feelings of guilt than those with lower levels of rejection.’ | N = 38 | N = 32 | 2.437 | 68.0 | 0.017 |

| M = 61.4 | M = 54.2 | ||||

| SD = 12.8 | SD = 11.7 | ||||

| Mdn. = 65.0 | Mdn. = 53.0 | ||||

| SE = 2.07 | SE = 2.08 | ||||

| High abuse | Low abuse | ||||

| (H3) ‘Children and teenagers with higher levels of abuse will report more shame than those with lower levels of abuse.’ | N = 82 | N = 74 | −2.02 | 154 | 0.045 |

| M = 60.0 | M = 54.1 | ||||

| SD = 18.0 | SD = 18.8 | ||||

| Mdn. = 60.0 | Mdn. = 52.0 | ||||

| SE = 1.98 | SE = 2.18 | ||||

| High abuse | Low abuse | ||||

| (H4) ‘Children and teenagers with higher levels of abuse will report more guilt than those with lower levels of abuse.’ | N = 74 | N = 82 | 3.20 | 154 | 0.002 |

| M = 64.7 | M = 58.8 | ||||

| SD = 11.2 | SD = 11.7 | ||||

| Mdn. = 66.0 | Mdn. = 61.0 | ||||

| SE = 1.31 | SE = 1.30 | ||||

| Institutional care | Family environment | ||||

| (H5) ‘Children and teenagers raised in institutional care will report higher levels of shame than children raised in family environments.’ | N = 58 | N = 94 | −5.27 | 150 | <0.001 |

| M = 65.8 | M = 50.6 | ||||

| SD = 19.0 | SD = 16,1 | ||||

| Mdn. = 64.0 | Mdn. = 49.0 | ||||

| SE = 2.50 | SE = 1.66 | ||||

| Institutional care | Family environment | ||||

| (H6) ‘Children and teenagers raised in institutional care will report higher levels of guilt than children raised in family environments.’ | N = 58 | N = 94 | 1.06 | 150 | 0.289 |

| M = 60.2 | M = 62.3 | ||||

| SD = 12.5 | SD = 11.5 | ||||

| Mdn. = 61.0 | Mdn. = 65.0 | ||||

| SE = 1.64 | SE = 1.18 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexandrescu, V. Copiii Lui Irod: Raport Moral Asupra Copiilor Lasati in Grija Statului; Humanitas Inc.: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik, K.D.; Cox, D.W.; Kealy, D. Adverse childhood experiences and shame- and guilt-proneness: Examining the mediating roles of interpersonal problems in a community sample. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 98, 104233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuewig, J.; McCloskey, L.A. The relation of child maltreatment to shame and guilt among adolescents: Psychological routes to depression and delinquency. Child Maltreatment 2005, 10, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosim, I.; Runcan, P.; Runcan, R.; Jomiru, C.; Gavrila-Ardelean, M. The impact of parental external labour migration on the social sustainability of the next generation in developing countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, A. Successful domestic adoptions in a sample of adolescent Romanian adoptees. Today’s Child. Are Tomorrow’s Parents 2017, 44, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Runcan, P.L. The time factor: Does it influence the parent-child relationship? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 33, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- VandenBos, G.; APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association, Washington. ‘Child neglect’ 2007. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/child-neglect (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Bennett, D.S.; Sullivan, M.W.; Lewis, M. Neglected children, shame-proneness, and depressive symptoms. Child Maltreatment 2010, 15, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Onyido, J.A.; Akpan, B.G. Child Abandonment and its implications for educational development in Nigeria. Arch. Bus. Res. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, L.; Roberts, K.J.; Gandhi, N. Child violence experiences in institutionalised/orphanage care. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, P.J.; Kenney, J.W. Biological perspectives on the effects of early psychosocial experience. Dev. Rev. 2009, 29, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Cicchetti, D.; Hentges, R.F. Maternal unresponsiveness and child disruptive problems: The interplay of uninhibited temperament and dopamine transporter genes. Child Dev. 2015, 86, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clipa, O. Importanta Atitudinii Cadrelor Didactice Care au în Clasă Copii Adoptați Sau în Grija Asistenților Maternali, Abordarea Psihologică a Adopției și Asistenței Maternale the Importance of the Attitude of Teachers Who Have Adopted Children in Their Class or in the Care of Foster Assistants, Psychological Approach to Adoption and Foster Care (coord. Violeta Enea); Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2021; pp. 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ogelman, H.G. Predictor effect of parental acceptance-rejection levels on resilience of preschool children. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turliuc, M.N.; Marici, M. What do Romanian parents and adolescents have conflicts about? Rev. Cercet. Si Interv. Soc. 2013, 42, 28–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner, R.P. The parental “acceptance-rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdibegoviü, E.; Brkiü, M. Child neglect-causes and consequences. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Nsabimana, E.; Rutembesa, E.; Wilhelm, P.; Martin-Soelch, C. Effects of institutionalization and parental living status on children’s self-esteem, and externalizing and internalizing problems in Rwanda. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Palacios, J.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J.; Gunnar, M.R.; Vorria, P.; McCall, R.B.; LeMare, L.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Dobrova-Krol, N.A.; Juffer, F. Children in institutional care: Delayed development and resilience. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2011, 76, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deblinger, E.; Runyon, M.K. Understanding and treating feelings of shame in children who have experienced maltreatment. Child Maltreatment 2005, 10, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, H.B. Shame and Guilt in Neurosis; International Universities Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Covert, M.V.; Tangney, J.P.; Maddux, J.E.; Heleno, N.M. Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and interpersonal problem solving: A social cognitive analysis. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay-Hartz, J.; de Rivera, J.; Mascolo, M.F. Differentiating guilt and shame and their effects on motivation. In Self-Conscious Emotions: The Psychology of Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride; Tangney, J.P., Fischer, K.W., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 274–300. [Google Scholar]

- Meesters, C.; Muris, P.; Dibbets, P.; Cima, M.; Lemmens, L. On the link between perceived parental rearing behaviors and self-conscious emotions in adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Qi, J.; Zhen, R. Bullying victimization and adolescents’ social anxiety: Roles of shame and self-esteem. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, P. Parental Acceptance and Rejection, Gender, and Shame: Could the Acceptance of One Parent Act as a Buffer against Rejection of Another Parent? Master’s Thesis, California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Infant-mother attachment classification: Risk and protection in relation to changing maternal caregiving quality. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 38–58. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marici, M. Psycho-behavioral consequences of parenting variables in adolescents. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekowski, M.; Gambin, M.; Cudo, A.; Wozniak-Prus, M.; Penner, F.; Fonagy, P.; Sharp, C. The relations between childhood maltreatment, shame, guilt, depression and suicidal ideation in inpatient adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakvaag, H.F.; Thoresen, S.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Dyb, G.; Røysamb, E.; Olff, M. Broken and guilty since it happened: A population study of trauma-related shame and guilt after violence and sexual abuse. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 204, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, E.G.; Friedenberg, S.; LaRosa, A.; De Bellis, M.D.; Macias, M.M.; Summer, A.P.; Hulsey, T.C.; Runyan, D.K.; Brady, K.T. The effects of early neglect on cognitive, language, and behavioral functioning in childhood. Psychology 2012, 3, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rad, D.; Demeter, E. Youth Sustainable Digital Wellbeing. Postmod. Open 2019, 10, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiffen, V.E.; MacIntosh, H.B. Mediators of the link between childhood sexual abuse and emotional distress: A critical review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2005, 6, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Szentágotai-Tătar, A.; Miu, A.C. Individual differences in emotion regulation, childhood trauma and proneness to shame and guilt in adolescence. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bunea, O. Construcția Rezilienței de Către Tinerii Din Centrele de Plasament. Expert Projects, Iași. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ovidiu-Bunea/publication/336769112_Constructia_rezilientei_de_catre_tinerii_din_centrele_de_plasament/links/5db13238a6fdccc99d938f47/Constructia-rezilientei-de-catre-tinerii-din-centrele-de-plasament.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Andrews, J.L.; Ahmed, S.P.; Blakemore, S.J. Navigating the social environment in adolescence: The role of social brain development. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, S.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.D. Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, L.H. The teenage brain: Sensitivity to social evaluation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Runcan, R.; Runcan, P. Adolescence and stigma, a challenge in a changing society. Rev. Asistenţă Soc. 2023, 1, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.; Thomas, R. Psychological differences in shame vs. guilt: Implications for mental health counselors. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2009, 31, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.M.; Purcell, R.; McGorry, P.D. Adolescent and young adult male mental health: Transforming system failures into proactive models of engagement. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62 (Suppl. S3), S9–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bertele, N.; Talmon, A.; Gross, J.J. Childhood maltreatment and narcissism: The mediating role of dissociation. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP9525–NP9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeter, E.; Rad, D. Global life satisfaction and general antisocial behavior in young individuals: The mediating role of perceived loneliness in regard to social sustainability—A preliminary investigation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, B.; Qian, M.; Valentine, J.D. Predicting depressive symptoms with a new measure of shame: The Experience of Shame Scale. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 41, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P. Evolution, social roles, and the differences in shame and guilt. Soc. Res. 2003, 70, 1205–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; Mercy, J.A.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Zwi, A.B. The world report on violence and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, W.H.; Schratter, A.K.; Kugler, K. The guilt inventory. Psychol. Rep. 2000, 87, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R.P.; Ali, S. Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ). In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Fink, L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A Retrospective Self-Report Manual; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 12, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Debnath, R.; Tang, A.; Zeanah, C.H.; Nelson, C.A.; Fox, N.A. The long-term effects of institutional rearing, foster care intervention and disruptions in care on brain electrical activity in adolescence. Dev. Sci. 2020, 23, e12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, J.G.; Toth, S.L.; Cicchetti, D.; Bruce, J.; Kane, P.; Daddis, C. Maltreated and nonmaltreated preschoolers’ conceptions of hypothetical and actual moral transgressions. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbairn, W.R.D. Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kealy, D.; Rice, S.M.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S.; Spidel, A. Childhood trauma and somatic symptoms among psychiatric outpatients: Investigating the role of shame and guilt. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 268, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.L. Shame and Guilt; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.L.; Adluru, N.; Chung, M.K.; Alexander, A.L.; Davidson, R.J.; Pollak, S.D. Early neglect is associated with alterations in white matter integrity and cognitive functioning. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 1566–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Judge, S. Developmental recovery and deficit in children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2003, 34, 49–62. Available online: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1025302025694 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Sánchez-Núñez, M.-J.; Sadurní-Brugué, M.; Ibañez-Fanés, M. Factores de riesgo de maltrato y representaciones de apego en niños que viven en una residencia de protección a la infancia [Abuse risk factors and attachment representations in children living in a child protection residence]. Rev. De Psicopatología Y Salud Ment. Del Niño Y Del Adolesc. 2022, 40, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Marici, M. A holistic perspective of the conceptual framework of resilience. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 2015, 23, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Marici, M.; Turliuc, M.N. How much does it matter? Exploring the role of parental variables in school deviance in Romania. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 2011, 19, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Povian, G.; Runcan, P.L. Groups with special needs in community measures: Stigma and discrimination of HIV-positive people. In Proceedings of the International Conference Multidisciplinary Perspectives in the Quasi-Coercitive Treatment of Offeders (SPECTO), Timisoara, Romania, 13–14 September 2018; pp. 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, K.M.; Baldwin, J.R.; Ewald, T. The relationship among shame, guilt, and self-efficacy. Am. J. Psychother. 2006, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S | G | PN | EN | SA | PA | EA | PR | MR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | M = 57.0 SD = 18.7 N = 230 | - | ||||||||

| G | M = 61.6 SD = 11.8 N = 230 | −0.496 ** | - | |||||||

| PN | M = 8.4 SD = 3.8 N = 226 | 0.347 ** | −0.415 ** | - | ||||||

| EN | M = 10.6 SD = 5.1 N = 226 | 0.146 | −0.228 ** | 0.39 ** | - | |||||

| SA | M = 6.04 SD = 3.04 N = 226 | 0.288 ** | −0.360 ** | 0.575 ** | 0.373 *** | - | ||||

| PA | M = 7.6 SD = 4.1 N = 226 | 0.332 ** | −0.400 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.509 *** | 0.611 ** | - | |||

| EA | M = 10.2 SD = 5.4 N = 226 | 0.474 ** | −0.510 ** | 0.532 ** | 0.686 *** | 0.489 ** | 0.750 ** | - | ||

| PR | M = 18.6 SD = 15.7 N = 220 | 0.030 | 0.271 * | 0.292 *** | 0.397 ** | 0.240 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.454 ** | - | |

| MR | M = 13.8 SD = 12.4 N = 230 | 0.095 | 0.186 | 0.309 ** | 0.494 *** | 0.089 | 0.278 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.463 *** | - |

| A | M = 17.1 SD = 1.82 N = 230 | −0.224 ** | 0.072 | 0.295 ** | 0.198 ** | −0.091 | −0.095 | −0.068 | 0.068 | 0.068 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marici, M.; Clipa, O.; Runcan, R.; Pîrghie, L. Is Rejection, Parental Abandonment or Neglect a Trigger for Higher Perceived Shame and Guilt in Adolescents? Healthcare 2023, 11, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121724

Marici M, Clipa O, Runcan R, Pîrghie L. Is Rejection, Parental Abandonment or Neglect a Trigger for Higher Perceived Shame and Guilt in Adolescents? Healthcare. 2023; 11(12):1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121724

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarici, Marius, Otilia Clipa, Remus Runcan, and Loredana Pîrghie. 2023. "Is Rejection, Parental Abandonment or Neglect a Trigger for Higher Perceived Shame and Guilt in Adolescents?" Healthcare 11, no. 12: 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121724

APA StyleMarici, M., Clipa, O., Runcan, R., & Pîrghie, L. (2023). Is Rejection, Parental Abandonment or Neglect a Trigger for Higher Perceived Shame and Guilt in Adolescents? Healthcare, 11(12), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121724