Czech Women’s Point of Views on Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy due to BRCA Gene Mutation or Breast Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Treatment Procedure for Women with BRCA Mutations or Breast Cancer

2.2. Technical Possibilities of Breast Reconstruction

- Silicone implant;

- Tissue expander + silicone implant;

- Local flap + silicone implant;

- Reconstruction using own fat tissue (lipofilling);

- Distant pedunculated flap (latissimus dorsi flap);

- Free flaps via microsurgical transfer.

2.3. Questionnaire Study Design and Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Oncoplastic Surgery Program

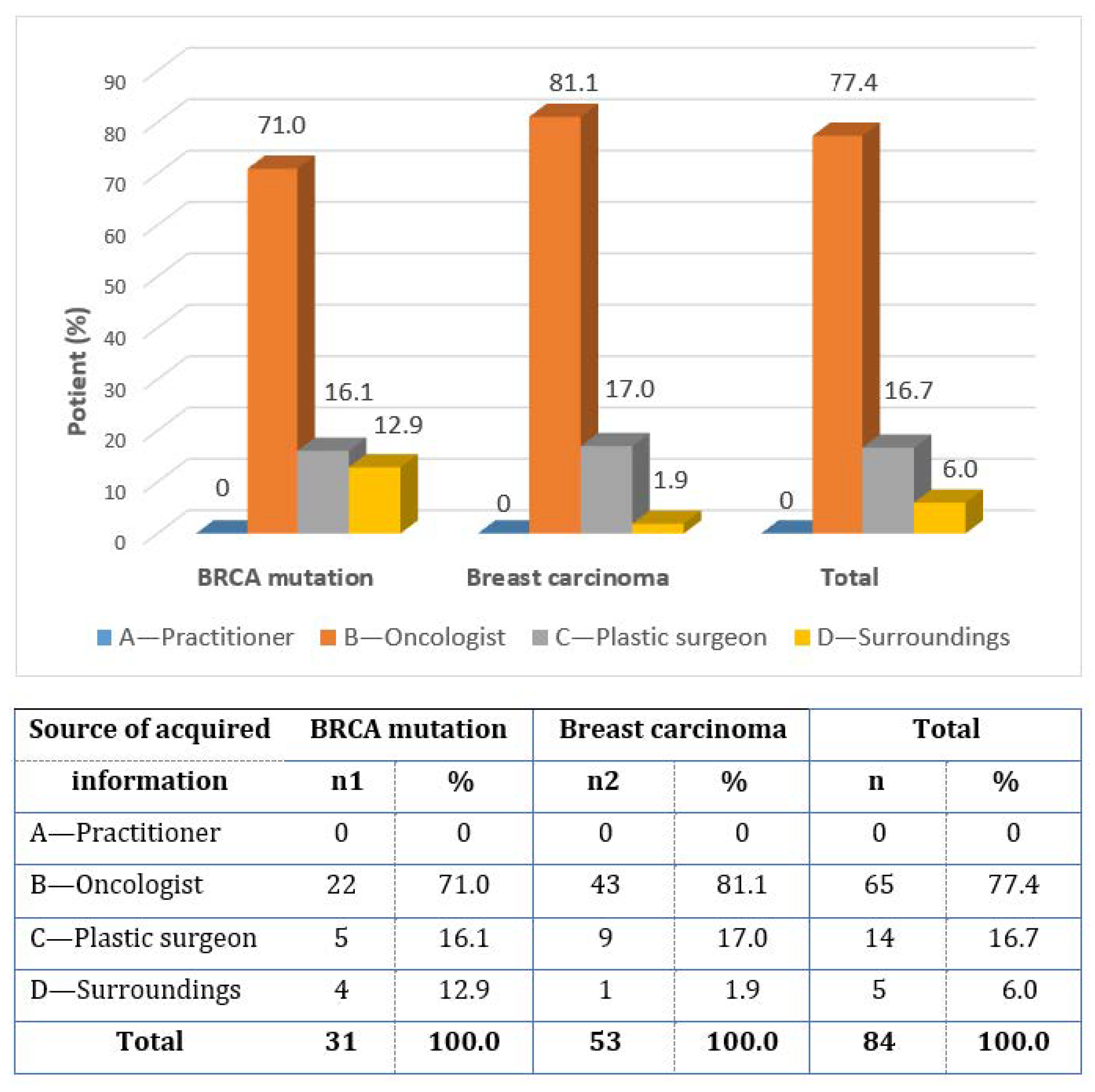

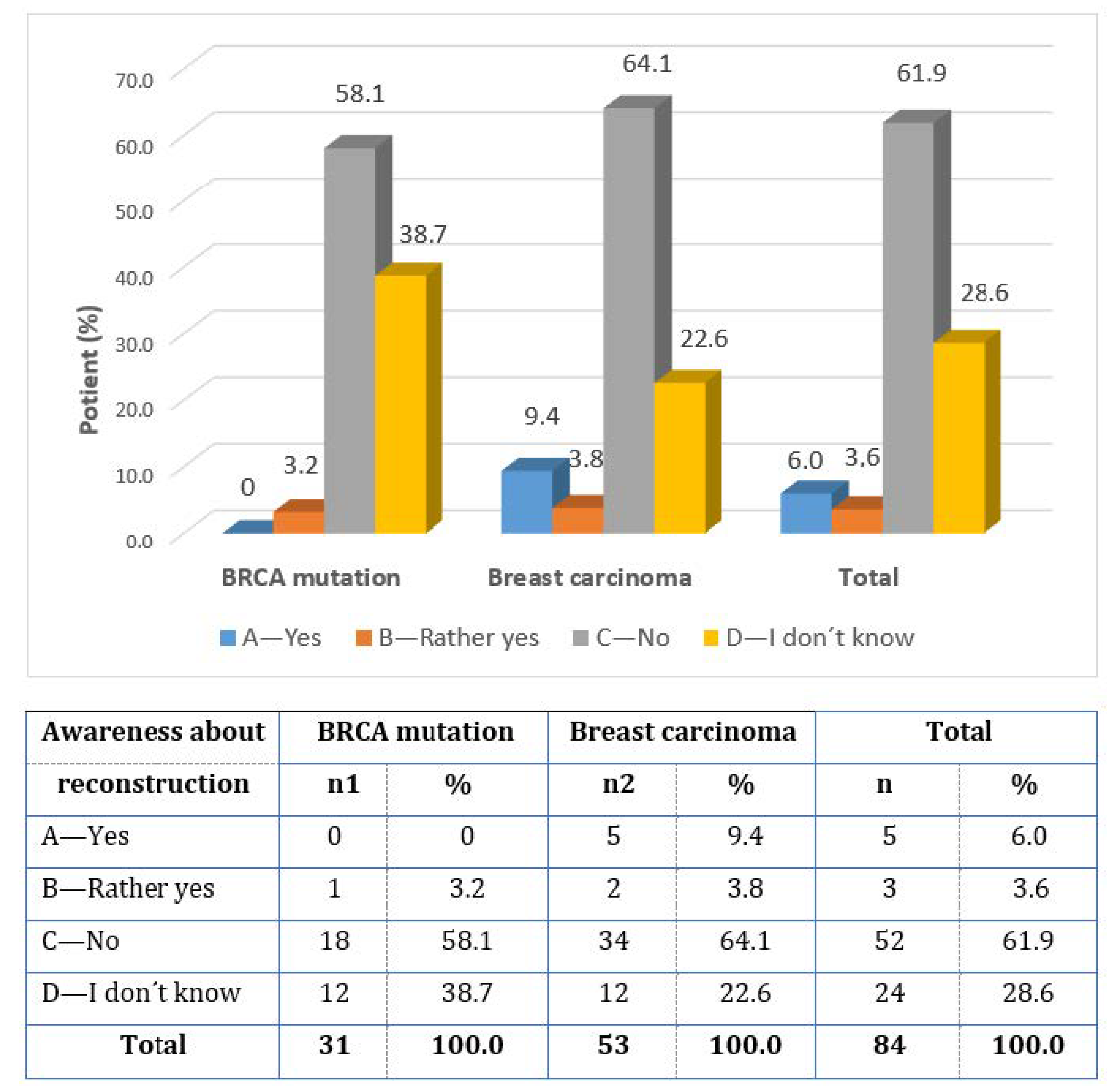

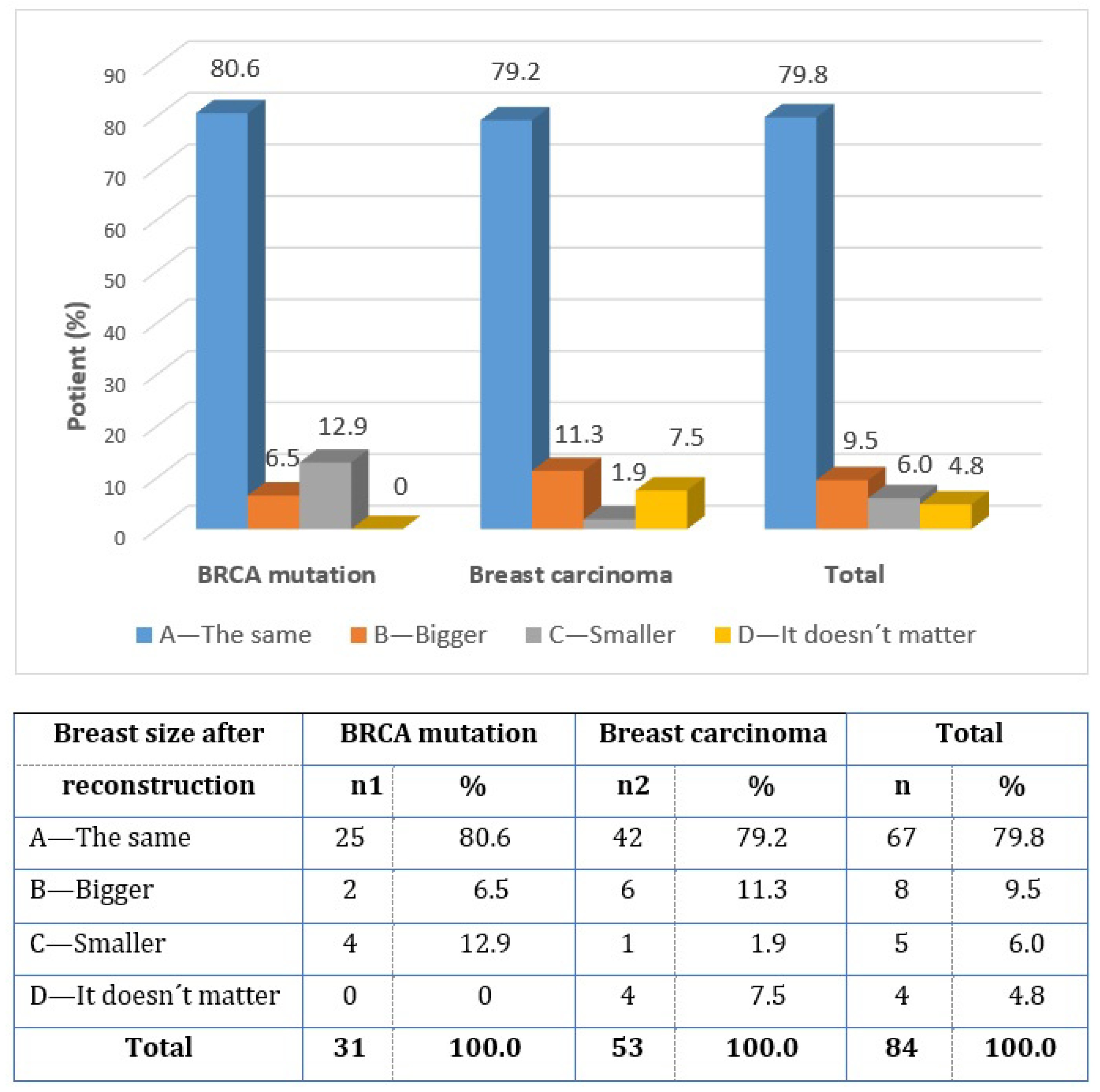

3.2. Questionnaire Survey

3.3. Evaluation of the Hypotheses of the Questionnaire Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan Fleege, N.M.; Cobain, E.F. Breast cancer management in 2021: A primer for the obstetrics and gynecology. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 82, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krejčí, D.; Pehalová, L.; Talábová, A.; Pokorová, K.; Katinová, I.; Mužík, J.; Dušek, L. Cancer Incidence in the Czech Republic 2018. Institute of Health Information and Statistics of the Czech Republic. Available online: https://www.uzis.cz/res/f/008352/novotvary2018.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Brančíková, D. Modern surgical and biological therapy of breast cancer. Ceska Gynekol. 2012, 77, 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Halászová, N.; Crha, I.; Huser, M.; Weinberger, V.; Žáková, J.; Ješeta, M.; Lousová, E.; Filipínská, E.; Ventruba, P. Fertility preserving methods in women with breast cancer before gonadotoxic therapy. Ceska Gynekol. 2017, 82, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chmelová, K.; Nováčková, M. Effect of manual lymphatic drainage on upper limb lymphedema after surgery for breast cancer. Ceska Gynekol. 2022, 87, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlakar, I.; Lin, S.; Nateqi, J.; Gruarin, S.; Diéguez, L.; Piairo, P.; Pires, L.R.; Tement, S.; Aleksandraviča, I.; Leja, M.; et al. Establishing an Expert Consensus on Key Indicators of the Quality of Life among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Modified Delphi Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foretova, L.; Petrakova, K.; Palacova, M.; Kalabova, R.; Navratilova, M.; Lukesova, M.; Vasickova, P.; Machackova, E.; Kleibl, Z.; Pohlreich, P. Genetic and preventive services for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in the Czech Republic. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2006, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co, M.; Liu, T.; Leung, J. Breast Conserving Surgery for BRCA Mutation Carriers—A Systematic Review. Clin. Breast Cancer 2020, 20, e244–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.G.; Davey, C.M.; Ryan, É.J.; Lowery, A.J.; Kerin, M.J. Combined breast conservation therapy versus mastectomy for BRCA mutation carriers—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast 2021, 56, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateju, M.; Stribrna, J.; Zikan, M.; Kleibl, Z.; Janatova, M.; Kormunda, S.; Novotny, J.; Soucek, P.; Petruzelka, L.; Pohlreich, P. Population-based study of BRCA1/2 mutations: Family history based criteria identify minority of mutation carriers. Neoplasma 2010, 57, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valachis, A.; Nearchou, A.D.; Lind, P. Surgical management of breast cancer in BRCA-mutation carriers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 144, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagura, N.; Hayashi, N.; Takei, J.; Yoshida, A.; Ochi, T.; Iwahira, Y.; Yamauchi, H. Breast reconstruction after risk-reducing mastectomy in BRCA mutation carriers. Breast Cancer (Tokyo Jpn.) 2020, 27, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, D.; Tanaka, Y.; Tsubota, Y.; Sueoka, N.; Endo, K.; Ogura, T.; Nagumo, Y.; Kwon, A.H. Immediate breast reconstruction for breast cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho = Jpn. J. Cancer Chemother. 2014, 41, 1892–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, T.N.S.; Zhong, L.; Momoh, A.O.; Chung, K.C.; Waljee, J.F. Improved Rates of Immediate Breast Reconstruction at Safety Net Hospitals. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventruba, T.; Brančíková, D.; Ventruba, P.; Minář, L.; Felsinger, M.; Vomela, J. Breast reconstruction in patients with BRCA mutation and breast cancer- our approach. Ceska Gynek. 2021, 86, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coufal, O.; Gabrielová, L.; Justan, I.; Zapletal, O.; Selingerová, I.; Krsička, P. Breast cancer patient satisfaction with immediate two-stage implant-based breast reconstruction. Klin. Onkol. 2014, 27, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.L.; Wetzel, C.M.; Lange, K.W.; Heine, N.; Ortmann, O. Patients’ experience of breast reconstruction after mastectomy and its influence on postoperative satisfaction. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 296, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santanelli di Pompeo, F.; Paolini, G.; Firmani, G.; Sorotos, M. History of breast implants: Back to the future. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2022, 32, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dražan, L.; Veselý, J.; Hýža, P.; Kubek, T.; Foretová, L.; Coufal, O. Chirurgická prevence karcinomu prsu pacientek s dědičným rizikem. Klin. Onkol. 2012, 25, S78–S83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vallard, A.; Magné, N.; Guy, J.B.; Espenel, S.; Rancoule, C.; Diao, P.; Deutsch, E.; Rivera, S.; Chargari, C. Is breast-conserving therapy adequate in BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers? The radiation oncologist’s point of view. Br. J. Radiol. 2019, 92, 20170657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Tribune 24.5.2016 Onkoplastická Chirurgie Přináší do Života Kvalitu. Available online: https://www.tribune.cz/archiv/onkoplasticka-chirurgie-prinasi-do-zivota-kvalitu/ (accessed on 24 May 2016).

- Ventruba, T.; Minář, L.; Brančíková, D.; Protivankova, M.; Ventruba, P. 131P Immediate breast reconstruction in patients with BRCA mutation and breast cancer- our approach. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33 (Suppl. S3), S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventrubová, G. Breast Reconstruction from the Patient’s Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Inštitút Dr. Pavla Blahu, Skalica, University of Health and Social Work St. Elizabeth, Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.J.; Nie, X.Y.; Ji, C.C.; Lin, X.X.; Liu, L.J.; Chen, X.M.; Yao, H.; Wu, S.H. Long-Term Cardiovascular Risk After Radiotherapy in Women With Breast Cancer. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, K.K.; Neuner, J.; Butler, A.; Geurts, J.L.; Kong, A.L. Risk reduction and survival benefit of prophylactic surgery in BRCA mutation carriers, a systematic review. Am. J. Surg. 2016, 212, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangkhoee, H.; Matros, E.; Disa, J. Trends and concepts in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevan, R. Reconstructive utilisation and outcomes following mastectomy surgery in women with breast cancer treated in England. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2019, 102, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, M.; Brunnbauer, M.; Scheithauer, H.; Hamann, U.; Braun, M.; Pölcher, M. Quality of life in breast cancer patients and surgical results of immediate tissue expander/implant-based breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 300, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H.; Diaz, R.; Orman, A.G. Breast Reconstruction and Radiation Therapy. Cancer Control 2018, 25, 1073274818795489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allué Cabañuz, M.; Arribas Del Amo, M.D.; Gil Romea, I.; Val-Carreres Rivera, M.P.; Sousa Domínguez, R.; Güemes Sánchez, A.T. Direct-to-implant breast reconstruction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A safe option? Cir. Esp. 2019, 97, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billig, J.; Jagsi, R.; Qi, J.; Hamill, J.B.; Kim, H.M.; Pusic, A.L.; Buchel, E.; Wilkins, E.G.; Momoh, A.O. Should Immediate Autologous Breast Reconstruction Be Considered in Women Who Require Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy? A Prospective Analysis of Outcomes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 139, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, R.H.; Gray, S.W.; Romantan, A.; Kelly, B.J.; DeMichele, A.; Armstrong, K.; Schwartz, J.S.; Hornik, R.C. Differences in information seeking among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients: Results from a population-based survey. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 81, S54–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durry, A.; Baratte, A.; Mathelin, C.; Bruant-Rodier, C.; Bodin, F. Patients’ satisfaction after immediate breast reconstruction: Comparison between five surgical techniques. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2019, 64, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventruba, T.; Ventruba, P.; Ješeta, M. Immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy from the patient’s point of view. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ventruba, T.; Ješeta, M.; Minář, L.; Vomela, J.; Brančíková, D.; Žáková, J.; Ventruba, P. Czech Women’s Point of Views on Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy due to BRCA Gene Mutation or Breast Cancer. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121755

Ventruba T, Ješeta M, Minář L, Vomela J, Brančíková D, Žáková J, Ventruba P. Czech Women’s Point of Views on Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy due to BRCA Gene Mutation or Breast Cancer. Healthcare. 2023; 11(12):1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121755

Chicago/Turabian StyleVentruba, Tomáš, Michal Ješeta, Luboš Minář, Jindřich Vomela, Dagmar Brančíková, Jana Žáková, and Pavel Ventruba. 2023. "Czech Women’s Point of Views on Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy due to BRCA Gene Mutation or Breast Cancer" Healthcare 11, no. 12: 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121755

APA StyleVentruba, T., Ješeta, M., Minář, L., Vomela, J., Brančíková, D., Žáková, J., & Ventruba, P. (2023). Czech Women’s Point of Views on Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy due to BRCA Gene Mutation or Breast Cancer. Healthcare, 11(12), 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121755