Association between Death or Hospitalization and Observable Variables of Eating and Swallowing Function among Elderly Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

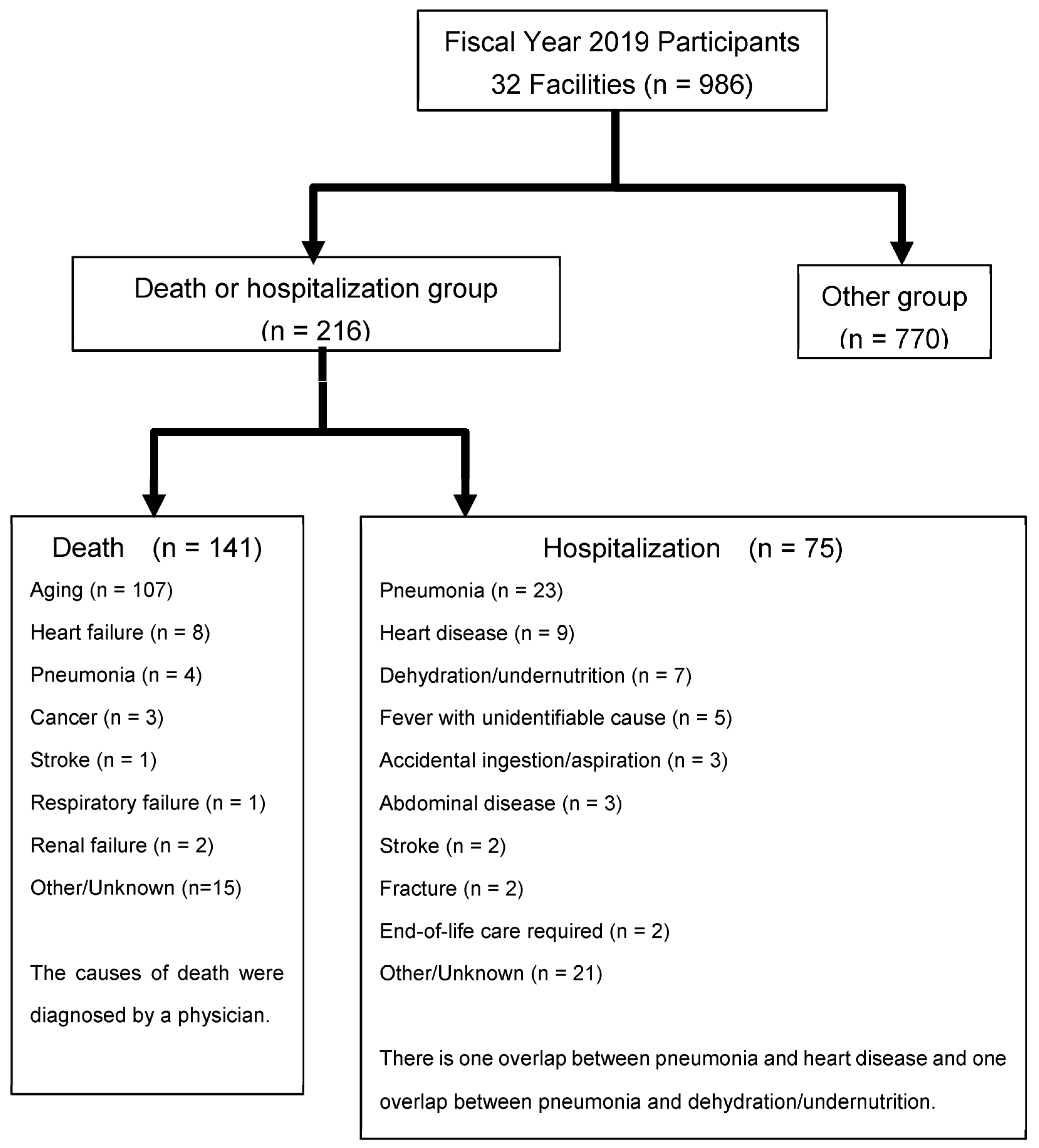

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Survey Items

2.3.1. Basic Information

2.3.2. Daily Living Function and Cognitive Function

2.3.3. Oral Status

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Generalizability

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Igarashi, K.; Kikutani, T.; Tamura, F. Survey of suspected dysphagia prevalence in home-dwelling older people using the 10-Item Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, R.; Dziewas, R.; Beck, A.M.; Clave, P.; Heppner, H.J.; Langmore, S.; Leischker, A.; Martino, R.; Pluschinski, P.; Rösler, A.; et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons—From pathophysiology to adequate intervention: A review and summary of an international expert meeting. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Williams, K.; Batchelor-Murphy, M.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Hein, M. Eating performance in relation to intake of solid and liquid food in nursing home residents with dementia: A secondary behavioral analysis of mealtime videos. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 96, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocdor, P.; Siegel, E.R.; Giese, R.; Tulunay-Ugur, O.E. Characteristics of dysphagia in older patients evaluated at a tertiary center: Characteristics of dysphagia in older patients. Laryngoscope 2015, 125, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, W.Y.; Lee, T.H.; Ham, N.S.; Park, J.W.; Lee, Y.G.; Cho, S.J.; Lee, J.S.; Hong, S.J.; Jeon, S.R.; Kim, H.G.; et al. Adding endoscopist-directed flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing to the videofluoroscopic swallowing study increased the detection rates of penetration, aspiration, and pharyngeal residue. Gut Liver 2015, 9, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell-Taylor, I. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in long-term care: Misperceptions of treatment efficacy. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, M.; Okada, K.; Kondo, M.; Taira, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Ito, K.; Nakajima, J.; Ozaki, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Nishi, Y.; et al. Factors associated with food form in long-term care insurance facilities. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsushita, T.; Taira, K.; Miura, K.; Ohara, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Ito, K.; Nakajima, J.; Iwasa, Y.; et al. Observational variables for considering a switch from a normal to a dysphagia diet among older adults requiring long-term care: A one-year multicenter longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsushita, T.; Okada, K.; Ohara, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Ito, K.; Nakajima, J.; Iwasa, Y.; Itoda, M.; et al. Association between weight loss and food form in older individuals residing in long-term care facilities: 1-year multicenter longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.-Y.; Wu, T.-H.; Liu, C.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, C.-C.; Lai, M.-M.; Lin, W.-Y. Body mass index and albumin levels are prognostic factors for long-term survival in elders with limited performance status. Aging 2020, 12, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. Functional evaluation: The Barthel index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993, 43, 2412–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, A.; Senger, M.; Lötzbeyer, T.; Gefeller, O.; Sieber, C.C.; Volkert, D. Effects of a texture-modified, enriched, and reshaped diet on dietary intake and body weight of nursing home residents with chewing and/or swallowing problems: An Enable study. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 38, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, R.; Kikutani, T.; Yoshida, M.; Yamashita, Y.; Hirayama, Y. Prognosis-related factors concerning oral and general conditions for homebound older adults in Japan: Prognosis-related factors for homebound. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzuya, M. Nutritional assessment and nutritional management for the elderly. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 2003, 40, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziewas, R.; Auf dem Brinke, M.; Birkmann, U.; Bräuer, G.; Busch, K.; Cerra, F.; Damm-Lunau, R.; Dunkel, J.; Fellgiebel, A.; Garms, E.; et al. Safety and clinical impact of FEES—Results of the FEES-Registry. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2019, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, S.B.; Murray, J.T. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 19, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Harris, B.; Jones, B. The videofluorographic swallowing study. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 19, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoshino, D.; Watanabe, Y.; Edahiro, A.; Kugimiya, Y.; Igarashi, K.; Motokawa, K.; Ohara, Y.; Hirano, H.; Myers, M.; Hironaka, S.; et al. Association between simple evaluation of eating and swallowing function and mortality among patients with advanced dementia in nursing homes: 1-year prospective cohort study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 87, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Shimazaki, Y.; Nonoyama, T.; Tadokoro, Y. Association of oral health factors related to oral function with mortality in older Japanese. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, S.; Ohara, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Edahiro, A.; Motokawa, K.; Shirobe, M.; Furuya, J.; Watanabe, Y.; Suga, T.; Kanehisa, Y.; et al. Relationship between mortality and oral function of older people requiring long-term care in rural areas of Japan: A four-year prospective cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Edahiro, A.; Motokawa, K.; Shirobe, M.; Hirano, H.; Ito, K.; Kanehisa, Y.; Yamada, R.; Yoshihara, A. Self-feeding ability as a predictor of mortality japanese nursing home residents: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A.L.; Rogus-Pulia, N. Temporal associations between caregiving approach, behavioral symptoms and observable indicators of aspiration in nursing home residents with dementia. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.H.; Han, H.R.; Oh, B.M.; Lee, J.; Park, J.A.; Yu, S.J.; Chang, H. Prevalence and associated factors of dysphagia in nursing home residents. Geriatr. Nurs. 2013, 34, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Edahiro, A.; Motokawa, K.; Shirobe, M.; Yasuda, J.; Murakami, M.; Murakami, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Furuta, J.; et al. Relationship between mortality and Council of Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire scores in Japanese nursing home residents. Nutrition 2019, 57, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humagain, M.; Humagain, R.; Rokaya, D. Dental practice during COVID-19 in Nepal: A descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2020, 58, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Language | able to speak | able to speak but with poor articulation | not able to speak |

| Drooling | no drooling | occasional drooling | always drooling. |

| Halitosis | no halitosis | a little halitosis | a lot of halitosis |

| Masticatory movement | has movement | moves when spoken to | almost no movement |

| Tongue movement | almost complete movement | movement but within a small range | no movement |

| Perioral muscle function | movement | slight difficulty | no movement |

| Left-right asymmetric movement of the mouth angle | no | yes | |

| Swallowing | possible | delayed but possible | |

| Coughing | no coughing | coughing | |

| Changes in voice quality after swallowing | no abnormality | abnormality present. | |

| Respiration after swallowing | no abnormality | shallow and fast breathing | |

| Rinsing | able to rinse completely | inadequate rinsing | unable to rinse |

| Oral residue | none | a small amount | present |

| Variable | Overall (n = 986) | Death or Hospitalization (n = 216) | Other (n = 770) | p-Value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median, [Q1, Q3] | Mean ± SD | Median, [Q1, Q3] | Mean ± SD | Median, [Q1, Q3] | ||||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||||

| Age | 86.8 | ± | 7.9 | 88.0 [82.0, 92.0] | 88.5 | ± | 7.2 | 89.0 [84.0, 94.0] | 86.3 | ± | 8.0 | 87.0 [82.0, 92.0] | <0.001 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 781 | (79.9) | 156 | (72.9) | 625 | (81.8) | 0.004 | ||||||

| Body mass index (<18.5) | 597 | ± | (69.6) | 106 | ± | (56.7) | 491 | ± | (73.2) | <0.001 | |||

| Barthel Index (Total points) | 30.2 | ± | 26.4 | 25.0 [5.0, 45.0] | 20.8 | ± | 23.3 | 10.0 [0.0, 35.0] | 32.9 | ± | 26.7 | 30.0 [10.0, 50.0] | <0.001 |

| Clinical Dementia Rating (Total points) | |||||||||||||

| 0, 0.5 | 96 | (10.5) | 11 | (5.6) | 85 | (11.8) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1 | 127 | (13.9) | 21 | (10.7) | 106 | (14.8) | |||||||

| 2 | 231 | (25.3) | 40 | (20.4) | 191 | (26.6) | |||||||

| 3 | 460 | (50.3) | 124 | (63.3) | 336 | (46.8) | |||||||

| Simple evaluations (oral conditions) | |||||||||||||

| Language (possible) | 672 | (68.5) | 117 | (54.4) | 555 | (72.5) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Drooling (none) | 728 | (74.4) | 132 | (61.7) | 596 | (78.0) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Halitosis (none) | 571 | (58.3) | 104 | (48.6) | 467 | (61.0) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Masticatory movement (move) | 784 | (80.2) | 151 | (70.6) | 633 | (83.0) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Tongue movement (move) | 654 | (66.9) | 110 | (51.4) | 544 | (71.3) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Perioral muscle (move) | 727 | (74.4) | 127 | (59.6) | 600 | (78.5) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Left-right asymmetric movement of the mouth angle (not) | 860 | (88.6) | 187 | (87.8) | 673 | (88.8) | 0.688 | ||||||

| Swallowing (not) | 765 | (79.1) | 141 | (67.8) | 624 | (82.2) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Coughing (not) | 558 | (57.2) | 87 | (40.8) | 471 | (61.7) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Changes in voice quality after swallowing (not) | 809 | (83.2) | 155 | (72.8) | 654 | (86.2) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Respiration after swallowing (no abnormality) | 933 | (95.9) | 194 | (90.7) | 739 | (97.4) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Rinsing (possible) | 529 | (53.9) | 78 | (36.1) | 451 | (58.9) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Oral residue (none) | 482 | (49.3) | 76 | (35.3) | 406 | (53.3) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Evaluations (Oral Conditions) | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | ||||||

| Language (1, good; 2, bad) | 2.12 | ** | 1.66 | - | 2.69 | 1.50 | * | 1.01 | - | 2.22 |

| Drooling (1, no; 2, yes) | 2.09 | ** | 1.46 | - | 2.99 | 1.54 | * | 1.03 | - | 2.30 |

| Halitosis (1, no; 2, yes) | 1.60 | * | 1.19 | - | 2.15 | 1.49 | * | 1.09 | - | 2.04 |

| masticatory movement (1, good; 2, bad) | 2.09 | ** | 1.43 | - | 3.05 | 1.35 | 0.85 | - | 2.13 | |

| tongue movement (1, good; 2, bad) | 2.19 | ** | 1.63 | - | 2.94 | 1.51 | 0.96 | - | 2.38 | |

| perioral muscle function (1, good; 2, bad) | 2.29 | ** | 1.68 | - | 3.13 | 1.73 | ** | 1.09 | - | 2.75 |

| Left-right asymmetric movement of the mouth angle (1, good; 2, bad) | 1.25 | 0.74 | - | 2.11 | 1.03 | 0.61 | - | 1.75 | ||

| Swallowing (1, good; 2, bad) | 2.09 | * | 1.29 | - | 3.38 | 1.42 | 0.81 | - | 2.49 | |

| Coughing (1, no; 2, yes) | 2.20 | ** | 1.51 | - | 3.21 | 1.60 | * | 1.07 | - | 2.38 |

| Changes in voice quality after swallowing (1, No abnormality; 2, abnormality) | 2.06 | * | 1.33 | - | 3.17 | 1.43 | 0.93 | - | 2.22 | |

| Respiration after swallowing (1, good; 2, bad) | 3.40 | ** | 1.88 | - | 6.17 | 2.19 | * | 1.21 | - | 3.98 |

| Rinsing (1, possible; 2, impossible) | 2.54 | ** | 1.99 | - | 3.23 | 2.02 | ** | 1.36 | - | 3.00 |

| Oral residue (1, no; 2, yes) | 1.97 | ** | 1.46 | - | 2.66 | 1.66 | * | 1.13 | - | 2.43 |

| OR | 95%CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 | ** | 1.01 | - | 1.06 |

| Sex (1, male; 2, female) | 1.63 | * | 1.22 | - | 2.19 |

| Body mass index | 0.50 | ** | 0.35 | - | 0.70 |

| Barthel Index | 0.98 | ** | 0.98 | - | 0.99 |

| Clinical Dementia Rating | |||||

| 0, 0.5 | Reference | ||||

| 1 | 1.52 | 0.69 | - | 3.37 | |

| 2 | 1.33 | 0.75 | - | 2.37 | |

| 3 | 2.36 | ** | 1.57 | - | 3.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takeda, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Taira, K.; Miura, K.; Ohara, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Ito, K.; Nakajima, J.; Iwasa, Y.; Itoda, M.; et al. Association between Death or Hospitalization and Observable Variables of Eating and Swallowing Function among Elderly Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131827

Takeda M, Watanabe Y, Taira K, Miura K, Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Ito K, Nakajima J, Iwasa Y, Itoda M, et al. Association between Death or Hospitalization and Observable Variables of Eating and Swallowing Function among Elderly Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(13):1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131827

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakeda, Maaya, Yutaka Watanabe, Kenshu Taira, Kazuhito Miura, Yuki Ohara, Masanori Iwasaki, Kayoko Ito, Junko Nakajima, Yasuyuki Iwasa, Masataka Itoda, and et al. 2023. "Association between Death or Hospitalization and Observable Variables of Eating and Swallowing Function among Elderly Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study" Healthcare 11, no. 13: 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131827