Reciprocal Effects between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction in Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Health Status

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Variable Definitions

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

3.2. Trajectory of Sleep Quality, Life Satisfaction, and Health Status of Older Adults

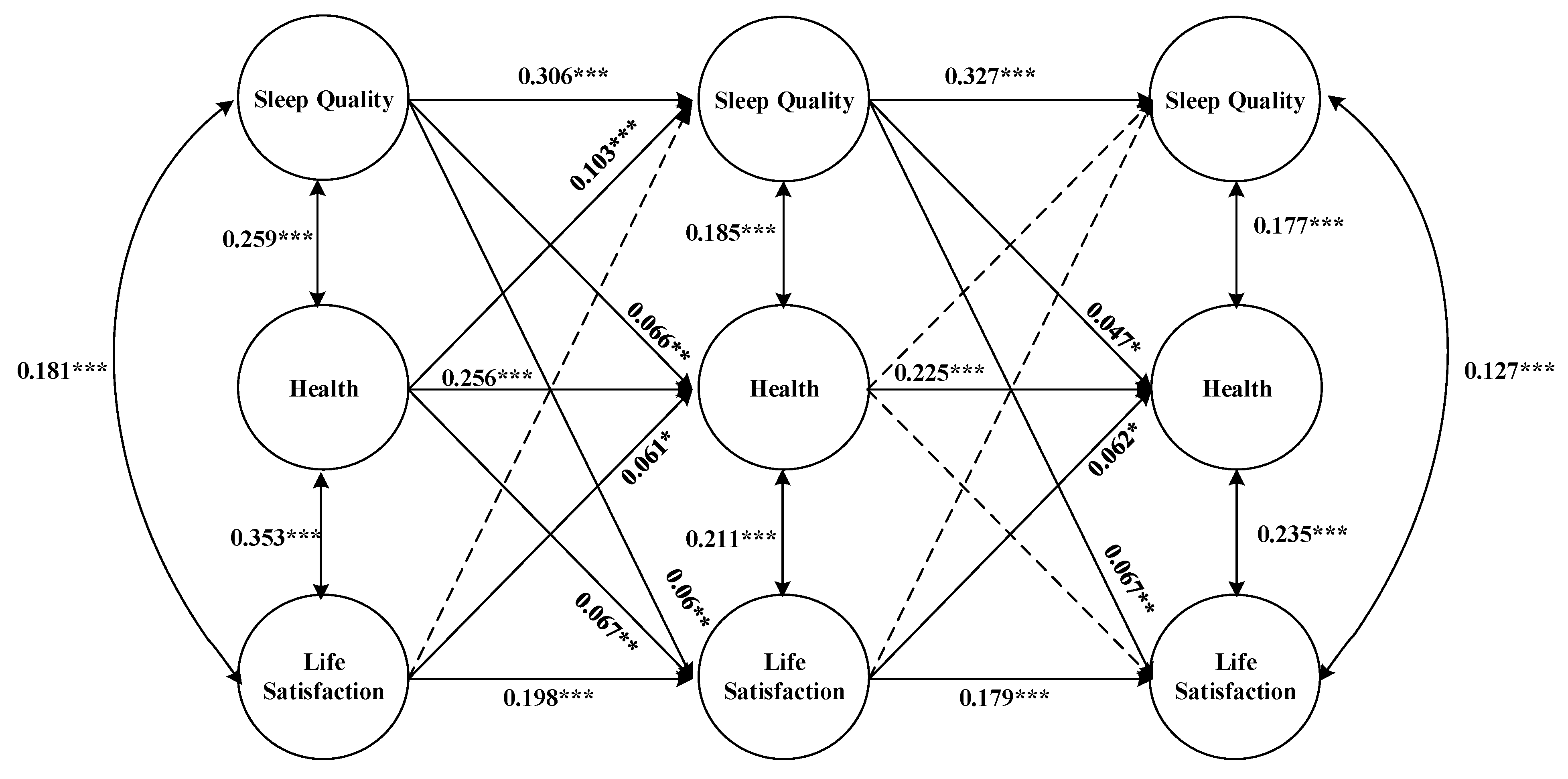

3.3. Reciprocal Relationship between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction

3.4. The Mediating Effect of Health Status in the Bidirectional Relationship between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Trajectory of Sleep Quality, Life Satisfaction, and Health Status of Older Adults

4.2. Analysis of Reciprocal Relationship between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction

4.3. Analysis of the Mediating Effect of Health Status in the Bidirectional Relationship between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction

5. Conclusions

6. Contributions and limitations

7. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R.; Zamarrón, M.D.; Ruíz, M.A. The contribution of socio-demographic and psychosocial factors to life satisfaction. Ageing Soc. 2001, 21, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghubach, R.; El-Rufaie, O.; Zoubeidi, T.; Sabri, S.; Yousif, S.; Moselhy, H.F. Subjective life satisfaction and mental disorders among older adults in UAE in general population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry A J. Psychiatry Late Life Allied Sci. 2010, 25, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaoláin, A.M.N.; Gallagher, D.; Connell, H.O.; Chin, A.; Bruce, I.; Hamilton, F.; Teehee, E.; Coen, R.; Coakley, D.; Cunningham, C. Subjective well-being amongst community-dwelling elders: What determines satisfaction with life? Findings from the Dublin Healthy Aging Study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, R.; Beheshti, S.S. An empirical study of the relationship between religiosity and life satisfaction. J. Soc. Sci. Ferdowsi Univ. Mashhad 2011, 8, 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez, J.C.; Tomás, J.M.; Oliver, A.; Navarro, E. Psychological and physical dimensions explaining life satisfaction among the elderly: A structural model examination. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 48, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-K.O.; Lee, J. Education, functional limitations, and life satisfaction among older adults in South Korea. Educ. Gerontol. 2013, 39, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-C. Trajectories and covariates of life satisfaction among older adults in Taiwan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 55, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Cong, Z.; Li, S. Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: Consequences for psychological well-being. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, S256–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liao, P.-A.; Chang, H.-H.; Sun, L.-C. National Health Insurance program and life satisfaction of the elderly. Aging Ment. Health 2012, 16, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R. Intergenerational family relations and life satisfaction among three elderly population groups in transition in the Israeli multi-cultural society. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2009, 24, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, A.; Katz, R.; Gur-Yaish, N. Reciprocity in parent–child exchange and life satisfaction among the elderly: A cross-national perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Sok, S.R. Relationships among the perceived health status, family support and life satisfaction of older K orean adults. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chi, I.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, G. Urban and rural factors associated with life satisfaction among older Chinese adults. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, G. Childlessness, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction among the elderly in China. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2007, 22, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, T.E.B.; Saksvik-Lehouillier, I. The relationships between life satisfaction and sleep quality, sleep duration and variability of sleep in university students. J. Eur. Psychol. Stud. 2018, 9, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhi, T.-F.; Sun, X.-M.; Li, S.-J.; Wang, Q.-S.; Cai, J.; Li, L.-Z.; Li, Y.-X.; Xu, M.-J.; Wang, Y.; Chu, X.-F. Associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with life satisfaction in elderly Chinese: The mediating role of depression. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 65, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, D.J.; Monjan, A.A.; Brown, S.L.; Simonsick, E.M.; Wallace, R.B.; Blazer, D.G. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: An epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep 1995, 18, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhu, G.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, Q.; Meng, H.; Hong, Z.; Ding, D. Prevalence and risk factors of poor sleep quality among Chinese elderly in an urban community: Results from the Shanghai aging study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benca, R.M. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic insomnia: A review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005, 56, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrie, J.E.; Shipley, M.J.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Brunner, E.; Miller, M.A.; Kumari, M.; Marmot, M.G. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: Associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep 2007, 30, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, S.R.; Hu, F.B. Short sleep duration and weight gain: A systematic review. Obesity 2008, 16, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knutson, K.L.; Van Cauter, E. Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1129, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowling, A.; Farquhar, M.; Grundy, E. Associations with changes in life satisfaction among three samples of elderly people living at home. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1996, 11, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strine, T.W.; Chapman, D.P.; Balluz, L.S.; Moriarty, D.G.; Mokdad, A.H. The associations between life satisfaction and health-related quality of life, chronic illness, and health behaviors among US community-dwelling adults. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Zulley, J.; Guilleminault, C.; Smirne, S.; Priest, R.G. How age and daytime activities are related to insomnia in the general population: Consequences for older people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Exner-Cortens, D.; Riffin, C.; Steptoe, A.; Zautra, A.; Almeida, D.M. Linking stable and dynamic features of positive affect to sleep. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodin, J.; McAvay, G. Determinants of change in perceived health in a longitudinal study of older adults. J. Gerontol. 1992, 47, P373–P384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Honkanen, R.; Viinamäki, H.; Heikkilä, K.; Kaprio, J.; Koskenvuo, M. Self-reported life satisfaction and 20-year mortality in healthy Finnish adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 152, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bihari, S.; Doug McEvoy, R.; Matheson, E.; Kim, S.; Woodman, R.J.; Bersten, A.D. Factors affecting sleep quality of patients in intensive care unit. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Healthy, Aging, Development, Studies. The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS)-Longitudinal Data (1998–2018); Peking University Open Research Data Platform: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, X.; Wen, Y.; Yang, L.; Lin, S.; Li, H.; Wu, S. Association between sleep and multimorbidity in Chinese elderly: Results from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS). Sleep Med. 2022, 98, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Sautter, J.; Pipkin, R.; Zeng, Y. Sociodemographic and health correlates of sleep quality and duration among very old Chinese. Sleep 2010, 33, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, D.G.; Diener, E. The pursuit of happiness. Sci. Am. 1996, 274, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E.; Brent Donnellan, M. Estimating the reliability of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from four national panel studies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffin, S.C.; Williams, A.B.; Mladen, S.N.; Perrin, P.B.; Dzierzewski, J.M.; Rybarczyk, B.D. Reciprocal effects between loneliness and sleep disturbance in older Americans. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwinski, M.; Hoffman, L.; Hofer, S.M. Evaluating convergence of within-person change and between-person age differences in age-heterogeneous longitudinal studies. Res. Hum. Dev. 2010, 7, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooneratne, N.S.; Vitiello, M.V. Sleep in older adults: Normative changes, sleep disorders, and treatment options. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 30, 591–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papi, S.; Karimi, Z.; Ghaed Amini Harooni, G.; Nazarpour, A.; Shahry, P. Determining the prevalence of sleep disorder and its predictors among elderly residents of nursing homes of Ahvaz city in 2017. Salmand Iran. J. Ageing 2019, 13, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowley, K. Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2011, 21, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, M.V.; Larsen, L.H.; Moe, K.E. Age-related sleep change: Gender and estrogen effects on the subjective–objective sleep quality relationships of healthy, noncomplaining older men and women. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 56, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillenbaum, G.G. Social context and self-assessments of health among the elderly. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1979, 20, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, B.S.; Linn, M.W. Objective and self-assessed health in the old and very old. Soc. Sci. Medicine. Part A Med. Psychol. Med. Sociol. 1980, 14, 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, K.; Sherman, D.W. Understanding the experience of caregivers: A focus on transitions. In Seminars in Oncology Nursing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, L.A.; Sumukadas, D. Optimal management of sarcopenia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2010, 5, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.E. Born to Be Mild? Cohort Effects Don’t (Fully) Explain Why Well-Being Is U-Shaped in Age; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Landeghem, B.G.M. Human Well-Being over the Life Cycle: Longitudinal Evidence from a 20-Year Panel. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 81, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gwozdz, W.; Sousa-Poza, A. Ageing, health and life satisfaction of the oldest old: An analysis for Germany. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papi, S.; Cheraghi, M. Relationship between life satisfaction and sleep quality and its dimensions among older adults in city of Qom, Iran. Soc. Work Public Health 2021, 36, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, N.H.M.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Haque, M. The Association between sleep quality and well-being amongst allied health sciences students in a public university in Malaysia. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2018, 8, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, T.; Lehto, S.M.; Hintikka, J.; Honkalampi, K.; Saharinen, T.; Viinamäki, H.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H. Biological and other health related correlates of long-term life dissatisfaction burden. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Short, M.A.; Louca, M. Sleep deprivation leads to mood deficits in healthy adolescents. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, B.; Bylsma, L.M.; Morris, B.H.; Rottenberg, J. Poor reported sleep quality predicts low positive affect in daily life among healthy and mood-disordered persons. J. Sleep Res. 2010, 19, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunio, T.; Korhonen, T.; Hublin, C.; Partinen, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Koskenvuo, M.; Kaprio, J. Longitudinal study on poor sleep and life dissatisfaction in a nationwide cohort of twins. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 169, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meerlo, P.; Sgoifo, A.; Suchecki, D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: Effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med. Rev. 2008, 12, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pan, H.; Pei, Y. Sleep duration and life satisfaction among older people in China: A longitudinal investigation. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-e.; Kim, J.K. How a good sleep predicts life satisfaction: The role of zero-sum beliefs about happiness. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spenceley, S.M. Sleep inquiry: A look with fresh eyes. Image J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1993, 25, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | Mean (n%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Continuous variable (60~116) | 80.52 |

| Gender | Male = 1; female = 0 | 52% |

| Region | Urban = 1; rural = 0 | 8% |

| Marriage | Married = 1; others = 0 | 62% |

| Education | Years of education (0~20) | 3.11 |

| Smoking | Smoked = 1; never smoked = 0 | 35% |

| Alcohol drinking | Drunk = 1; never drunk = 0 | 30% |

| Physical exercise | Yes = 1; no = 0 | 35% |

| Social security | Number of social security (0~7) | 1.37 |

| Cognition ability | MMSE value (0~30) | 26.38 |

| Sleep quality | Continuous variable (1~5) | 3.60 |

| Health status | Continuous variable (1~5) | 3.43 |

| Life satisfaction | Continuous variable (1~5) | 3.83 |

| Variables | 2011 | 2014 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality | 3.70 | 3.63 | 3.47 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.75 | 3.86 | 3.87 |

| Health status | 3.47 | 3.44 | 3.39 |

| Age | 77.22 | 80.11 | 84.23 |

| Gender | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| Region | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Years of education | 3.13 | 3.11 | 3.08 |

| Marriage | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.56 |

| Social security | 1.30 | 1.38 | 1.43 |

| Physical exercise | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| Cognition ability | 27.14 | 26.86 | 25.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, C.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Walsh, C.A. Reciprocal Effects between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction in Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Health Status. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131912

Zhu C, Zhou L, Zhang X, Walsh CA. Reciprocal Effects between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction in Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Health Status. Healthcare. 2023; 11(13):1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131912

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Change, Lulin Zhou, Xinjie Zhang, and Christine A. Walsh. 2023. "Reciprocal Effects between Sleep Quality and Life Satisfaction in Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Health Status" Healthcare 11, no. 13: 1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131912