Abstract

Purpose: This study evaluates the performance of the Early Intervention Physiotherapist Framework (EIPF) for injured workers. This study provides a proper follow-up period (3 years) to examine the impacts of the EIPF program on injury outcomes such as return to work (RTW) and time to RTW. This study also identifies the factors influencing the outcomes. Methods: The study was conducted on data collected from compensation claims of people who were injured at work in Victoria, Australia. Injured workers who commenced their compensation claims after the first of January 2010 and had their initial physiotherapy consultation after the first of August 2014 are included. To conduct the comparison, we divided the injured workers into two groups: physiotherapy services provided by EIPF-trained physiotherapists (EP) and regular physiotherapists (RP) over the three-year intervention period. We used three different statistical analysis methods to evaluate the performance of the EIPF program. We used descriptive statistics to compare two groups based on physiotherapy services and injury outcomes. We also completed survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier curves in terms of time to RTW. We developed univariate and multivariate regression models to investigate whether the difference in outcomes was achieved after adjusting for significantly associated variables. Results: The results showed that physiotherapists in the EP group, on average, dealt with more claims (over twice as many) than those in the RP group. Time to RTW for the injured workers treated by the EP group was significantly lower than for those who were treated by the RP group, indicated by descriptive, survival, and regression analyses. Earlier intervention by physiotherapists led to earlier RTW. Conclusion: This evaluation showed that the EIPF program achieved successful injury outcomes three years after implementation. Motivating physiotherapists to intervene earlier in the recovery process of injured workers through initial consultation helps to improve injury outcomes.

1. Introduction

Injuries or illnesses occurring at work have a substantial impact on individuals and society [1]. Although most injured workers can successfully recover and achieve a return to work (RTW) [2], RTW may take a longer time for many injured workers. RTW is a complicated process and can be impacted by different factors, including physical, psychological, social, and policy-related ones. There are several stages for an injured worker to get ready for RTW [3]. As the time that an injured worker is away from work gets longer, the likelihood of not returning to work increases [4]. Therefore, speedy and sustained RTW is the main goal of compensable injury systems, including those in Victoria, Australia, such as WorkSafe Victoria (WSV) and Transport Accident Commission (TAC). To reach this goal, early identification of undesired outcomes [5], such as delayed RTW, and early intervention [6] to prevent the undesired outcomes would be beneficial.

Physiotherapists and their early intervention play an important role in occupational rehabilitation [7] and, consequently, in reducing the post-injury cost [8] and improving RTW [9]. Also, the prominence of physiotherapy in treating musculoskeletal injuries is well recognized. However, the timing of the commencement of physiotherapy treatment, in other words, the time of physiotherapists’ intervention, is less clear [10]. Therefore, WSV, in collaboration with TAC, implemented the Early Intervention Physiotherapist Framework (EIPF) in 2014. The EIPF aimed to encourage physiotherapists who were working with compensable clients to work with clients early in the treatment program in relation to their RTW. The EIPF was implemented through an online training program for physiotherapists. This Framework was designed to encourage physiotherapists to engage clients in physical therapies early in the Occupational Rehabilitation (OR) process, with the aim of decreasing time to RTW and improving RTW sustainability. Once the program was successfully completed and a physiotherapist was accredited, higher fees were paid for services provided by these EIPF physiotherapists to encourage participation. WSV also provided incentives for physiotherapists who had their initial consultation for injured workers within 7 months post-injury [11].

An initial evaluation was undertaken immediately post-EIPF program delivery [12]. However, the duration of this evaluation was too short (3 months) to identify data trends and determine the impact of the program on RTW outcomes. In [12], the authors suggested that another evaluation should be undertaken with a sufficient follow-up period. In the current study, we initiated the second evaluation to examine the performance of the EIPF program three years after implementation in 2017. We also studied the differences in physiotherapy services and RTW outcomes for injured workers to examine the impact of the EIPF program on WSV clients.

1.1. Aims

This study aims to determine if the implementation of the EIPF program is associated with differences in the physiotherapy services provided or RTW outcomes for injured workers.

The study examines the following research questions:

RQ1. Are there differences in physiotherapy services provided to WSV clients between EIPF-trained physiotherapists (EP) and regular physiotherapists (RP) over the three-year intervention period (2014–2017)?

- Specifically, the type and number of services as well as the frequency of claims.

RQ2. Are there differences in the RTW outcomes of WSV clients treated by either EP or RP over the three-year intervention period (2014–2017)?

- Specifically, any difference between the time taken from the injury date to the RTW date, adjusting for explanatory variables (age, gender, type of injury, and occupation) as required.

The time to RTW is a common measure to evaluate the performance and success of injury intervention and healthcare improvement programs [13,14].

1.2. Definitions

The following definitions are used in the data analysis:

- EIPF—Early Intervention Physiotherapy Framework program (the intervention)

- EP—Physiotherapists who completed the EIPF program

- RP—Regular physiotherapists who did not complete the EIPF program

- WSV—WorkSafe Victoria.

2. Materials and Methods

To evaluate differences between types of physiotherapists and the effectiveness of the EIPF on client outcomes (addressing the research questions), a comparison of EP and RP was made. To assess the impact of the EIPF program, only claims which were served exclusively by physiotherapists of either the EP or RP group were analyzed. The manuscript complies with Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement [15] using the TRIPOD checklist that is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

TRIPOD checklist.

2.1. Data

The source of data is the Compensation Research Database (CRD) which was held by the Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research (ISCRR). The CRD includes the details of all claims, payments, services, hospital admissions, and medical certificates for WSV since 1985. It is an administrative database that is fully de-identified, and consent to use data for research purposes is obtained from clients [16,17]. The selection criteria for claims included in this study are as follows:

- Claims that had at least one day of wage compensation payment (standard time loss claims) with the injury date on or after the first of January 2010,

- Claims that had physiotherapy services provided either by EP or RP,

- Claims that had their initial physiotherapy consultation on or after the first of August 2014,

- If claims resulted in RTW, only claims with RTW on or after the date of initial consultation were included.

According to the selection criteria, 17,991 claims were identified, from which 7363 claims were served only by the EP group, 3998 claims were served only by the RP group, and 6630 claims were served by a mix of EP and RP groups. To provide a better investigation of the performance of the EIPF program, the claims in the mixed group were excluded from further analysis.

2.2. Outcomes

Time to RTW is calculated as the number of days between the injury date and the resumed work date. Comparing this outcome between two groups allows for an analysis of the effectiveness of the EIPF on client RTW outcomes.

2.3. Analysis

Different data analysis approaches have been used to answer the research questions. We used descriptive statistics to comprehensively compare the differences between the EP and RP groups in terms of physiotherapy services provided to clients and time to RTW.

We performed survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier curves to estimate the probability of RTW in each time interval. Kaplan–Meier curves are commonly used tools to analyze ‘time-to-event’ data [18]. These have been used widely in healthcare areas such as job survival of impaired employees [19] and vision loss after Diabetic Vitrectomy surgery [20]. In this study, we used the time to RTW in survival analysis.

We also used the log-rank test, which is a non-parametric test, to compare survival curves between two groups. The log-rank test, like the Kaplan–Meier curves, is used to compare two groups, e.g., treated versus the control group in a randomized trial. Also, the follow-ups can be divided into smaller time periods, and the number of occurrences within all time periods is compared. Similar to the Kaplan–Meier curves, the log-rank test should be used only when follow-ups are reasonably current. The log-rank test is limited to assessing the effect of just one variable at a time. A more complex method, such as the Cox model, should be considered for assessing multiple variables [21].

We assessed the association between time to RTW and claimants’ characteristics as predictors using univariate regression analysis. These predictors are gender, age, type of injury, and occupation. We also used multivariate regression to determine whether there is a difference in RTW outcomes achieved after adjusting for variables that are significantly associated with the RTW outcome.

3. Results

This section presents the results of data analysis on the evaluation of the EIPF program across EP and RP groups.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Description of Dataset

Table 2 summarizes the claimants’ characteristics for injured workers in the EP and RP groups. All percentages are out of the total population of each group. For age groups, our groups are aligned with the relevant studies derived from CRD [22]. For injury types and occupation groups, we kept the WSV-defined categories. The results show that the groups were not statistically different in terms of client age, gender, injury type, or occupation. This provides a fair baseline from which to compare the two groups based on physiotherapy services.

Table 2.

Distribution of injured workers based on characteristics in the EP and RP groups.

3.1.2. Services and Claims

In this section, we compare two groups in terms of physiotherapy services provided to clients (addressing RQ1). Physiotherapists use a variety of techniques (or services) to treat their clients and support them with RTW after injury. The average services per claim and average number of claims for each physiotherapist type (even if there were multiple physiotherapists servicing the claim) are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of injured workers based on characteristics in EP and RP groups.

The average number of claims each physiotherapist treated was significantly higher in the EP group than the RP one. In the EP group, each physiotherapist treated about 10 claims, whereas, in the RP group, each physiotherapist only treated 4–5 claims over the three-year period. The average number of services provided per claim was not different between the two groups.

3.1.3. Time to Achieving RTW

In this section, we evaluate differences between EP and RP groups based on time to RTW (addressing RQ2). Table 4 shows the results for the days taken from the injury date to the RTW date.

Table 4.

Time to RTW in EP and RP groups.

The results show that the time from the date of injury to the RTW date was significantly shorter (on average, about 3 weeks shorter) for clients treated by the EP group compared to the RP group.

3.1.4. Proportion Achieving RTW

In this section, we evaluate the difference between EP and RP groups based on the proportion of claims that had RTW for the periods of the whole three years and six months after injury. Table 5 below shows the RTW status of injured workers treated by the EP and RP groups over the full three-year evaluation period and at six months post-injury.

Table 5.

Proportion of RTW achieved by injured workers in the EP and RP groups.

The proportion of claims that had RTW was not different between the EP and RP groups overall; however, at 6 months post-injury, significantly more clients in the EP group had returned to work than the RP group. We will investigate this in more detail in the Survival Analysis.

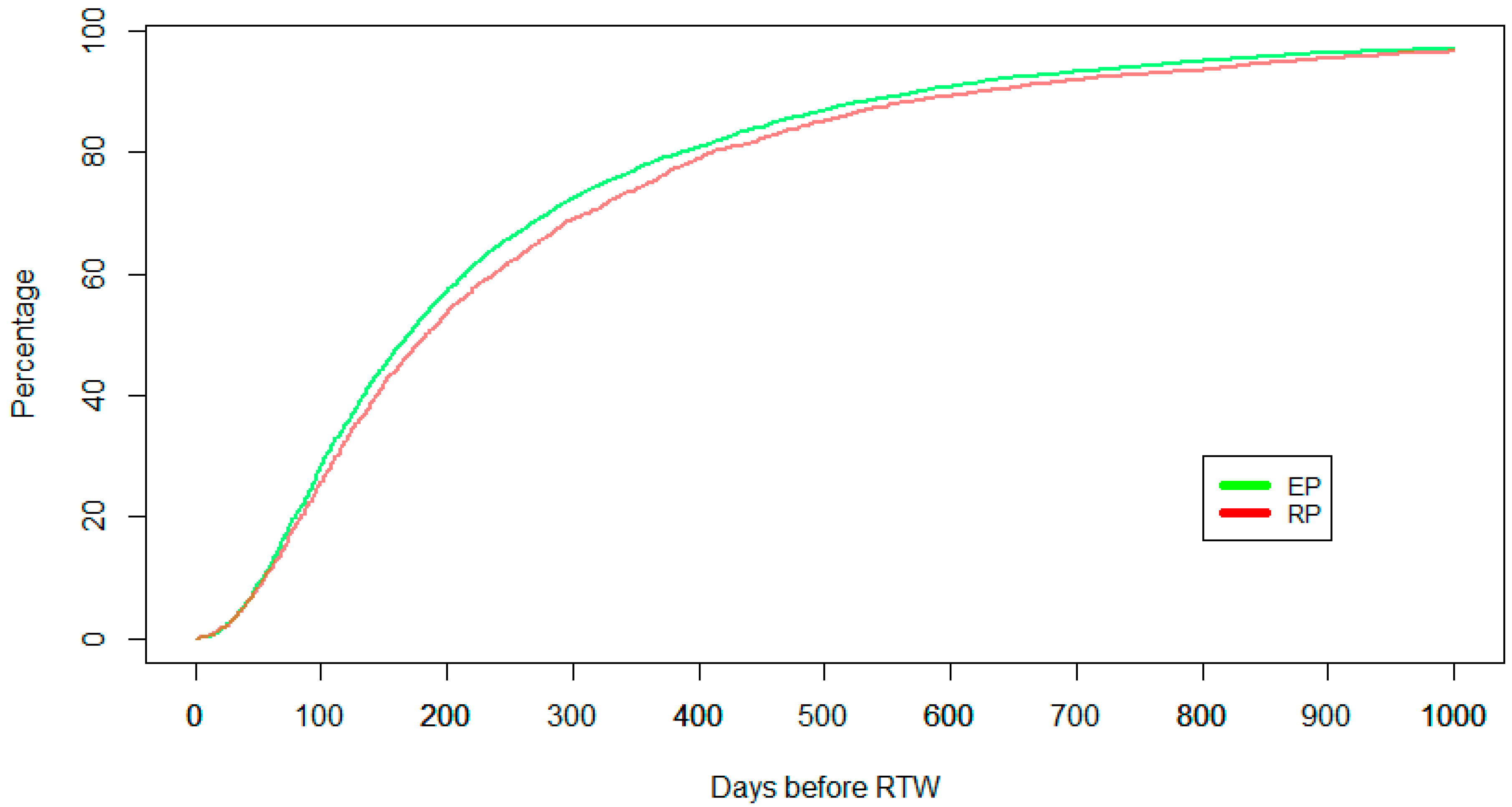

3.2. Survival Analysis

In this section, we perform survival analysis based on time to RTW (addressing RQ2). Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for EP and RP groups up to 1000 days post-injury (about three years). The Kaplan–Meier curves show that patients who have been served by physiotherapists who completed the EIPF program (EP) returned to work earlier than patients who visited regular physiotherapists (RP). We examine the significance of the difference between curves statistically using a log-rank test. The log-rank test shows that the difference in the time to RTW was statistically significant by physiotherapist type (EP vs. RP; χ2 statistic 10.58, p-value < 0.001) for all claims.

Figure 1.

Survival analysis for time to RTW from injury date over three years.

Table 6 presents the percentages of RTW and outputs of a log-rank test to examine the difference of Kaplan–Meier curves in the periods of 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months. It shows that the difference in the time to RTW becomes significant for clients who achieved their RTW in 2 years (χ2 statistic 6.94, p-value < 0.001) and in 3 years (χ2 statistic 12.1, p-value < 0.001) post-injury. Considering the results, the effectiveness of the EIPF program has been shown after 2 years (within 24 to 36 months). It supports the follow-up period of three years that has been taken for this study and suggested by [12].

Table 6.

Comparison of RTW percentage between EP and RP over time.

3.3. Regression Analysis

Regression analysis examines the association between time to RTW and the claimant’s characteristics. Only clients that were treated by either EP or RP groups were included, and both univariate and multivariate regression were used to examine the relationship between predictors and RTW outcomes. We use linear regression analysis. In the univariate regression model, each variable is the only predictor to predict the number of days to achieve RTW, and the p-value is calculated based on the t-test. In the multivariate regression model, all variables are included as predictors, and the p-value is calculated based on an F-test.

3.3.1. Univariate Analysis

Table 7 shows that age and injury type were significant predictors in determining RTW outcome. However, gender and occupation were not. There was also a significant difference in RTW outcomes by the physiotherapy group, with those in the EP group returning to work 21 days faster than the RP group.

Table 7.

Regression analysis with the outcome being the number of days to achieving RTW.

3.3.2. Multivariate Analysis

We created a multivariate model to perform the regression analysis. The multivariate model adjusted the time to RTW for age and injury type, given the observed statistical association, and examined differences between the outcome between EP and RP groups. A significant difference remained, with injured workers in the EP group still RTW 21 days faster than those in the RP group (Table 7).

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to describe the outcomes of an evaluation of the effects of the Early Intervention Physiotherapist Framework (EIPF) program on the return to work (RTW) outcomes for injured Victorian workers. The RTW outcomes were assessed three years after the initial implementation of the EIPF, and the effects on clients were examined in comparison with clients treated by physiotherapists not trained in the EIPF (RP group).

Within the examination period, comparing physiotherapists with EIPF training (EP group) to the RP group revealed the following results:

- Physiotherapists in the EP group visited more WSV clients per physiotherapist (average of 10.2 claims) than those in the RP group (average of 4.6 claims) over the three-year period.

- Injured workers returned to work on average 25 days sooner when treated by EP compared with RP. This could be a direct result of EIPF by motivating physiotherapists (EP group) for earlier post-injury intervention.

- Survival analysis showed that the clients of the EP group returned to work significantly faster than the RP group. After two years, this difference became statistically significant, as shown by the log-rank test, confirming the necessity of a three-year follow-up analysis such as that performed in this study.

- The time to return to work was significantly associated with age and injury type in both physiotherapy groups. Younger injured workers (between 15 and 24 years old) with fractures had returned to work faster, and the injured workers between 45 and 54 years old with musculoskeletal injuries had taken more time to get back to work.

- After adjusting age and injury type variables, injured workers in the EP group still returned to work significantly faster than those treated in the RP group (by 21 days). These results show that the difference between these two groups was substantially associated with the early intervention by EP physiotherapists post-injury.

The results support the positive findings of the initial study [12] on the EIPF program (3 months after initiating the program) in terms of adhering to EIPF goals and RTW outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is the use of a well-structured and population-based dataset to evaluate the performance of the early intervention program. The findings result in an insightful conclusion on the important factors that affect RTW outcomes.

The main limitation of this study is that the data are for injured workers in Victoria, Australia. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to every group of patients. The data we used in this study are administrative and payment data, which meant we relied on wage compensation to define RTW. Also, because the payment date for the physiotherapy services could be different from the actual date of receiving the service, the time to the first consultation session cannot be reliably calculated. Hence, we did not include this indicator in the analyses.

5. Conclusions

This evaluation has shown that three years after implementation, the EIPF resulted in positive outcomes for injured workers. More claims were managed by physiotherapists trained in EIPF than non-EIPF physiotherapists. The earlier intervention by physiotherapists (possibly within seven months after the injury) due to the incentives and the increased reimbursement provided by WSV for services led to a faster return to work and better outcomes for the injured worker.

The EIPF is achieving its aim of focusing on early intervention and sustainable return to work. Further monitoring of outcomes and performance will be important to ensure gains continue to be made on the time taken to the initial consultation post-injury, as it seems that any small improvement in this aspect can have a significant impact on the RTW outcomes of injured workers.

Further monitoring of outcomes and performance will be important to ensure gains continue to be made on the time taken to the initial consultation post-injury, as it seems that any small improvement in this aspect can have a significant impact on the RTW outcomes of injured workers. Early intervention programs and follow-up studies can be used in other allied health professions like chiropractic and osteopathy that play similar roles to physiotherapists in treating injured workers. In addition, the quality of the prediction by the conducted regression analysis can be investigated for future cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.K. and A.d.S.; methodology, H.A.K. and A.d.S.; validation, H.A.K., U.A. and A.d.S.; formal analysis, H.A.K.; investigation, H.A.K.; data curation, H.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.K.; writing—review and editing, H.A.K. and U.A.; visualization, H.A.K.; supervision, U.A. and A.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by WorkSafe Victoria (WSV) through the Institute of Safety, Compensation, and Recovery Research (ISCRR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This study was performed using a de-identified administrative dataset, with ethics approval granted by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (CF09/3150—2009001727).

Informed Consent Statement

Statement not required.

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be available publicly.

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by WorkSafe Victoria (WSV) through the Institute of Safety, Compensation, and Recovery Research (ISCRR). ISCRR is a joint initiative of WorkSafe Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission (TAC), and Monash University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berecki-Gisolf, J.; Collie, A.; McClure, R.J. Determinants of physical therapy use by compensated workers with musculoskeletal disorders. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2013, 23, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centre, T.S.R. Return to Work Survey—2016 (Australia and New Zealand). 2016. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1703/return-to-work-survey-2016-summary-research-report_0.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Park, J.; Roberts, M.R.; Esmail, S.; Rayani, F.; Norris, C.M.; Gross, D.P. Validation of the readiness for return-to-work scale in outpatient occupational rehabilitation in Canada. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2018, 28, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pransky, G.; Gatchel, R.; Linton, S.J.; Loisel, P. Improving return to work research. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2005, 15, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorshidi, H.A.; Haffari, G.; Aickelin, U.; Hassani-Mahmooei, B. Early identification of undesirable outcomes for transport accident injured patients using semi-supervised clustering. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 266, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, M.K.; Costa, D.S.J.; Linton, S.J.; Main, C.J.; Shaw, W.S.; Pearce, G.; Gleeson, M.; Pinto, R.Z.; Blyth, F.M.; McAuley, J.H.; et al. Implementation of Early Intervention Protocol in Australia for ‘High Risk’ Injured Workers is Associated with Fewer Lost Work Days over 2 Years Than Usual (Stepped) Care. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association, A.P. The Physiotherapists’ Role in Occupational Rehabilitation. 2012. Available online: https://www.physiotherapy.asn.au/DocumentsFolder/APAWCM/Advocacy/PositionStatement_2017_Thephysiotherapist%E2%80%99s_role_occ_rehabilitation.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Donovan, M.; Khan, A.; Johnston, V. The Contribution of Onsite Physiotherapy to an Integrated Model for Managing Work Injuries: A Follow Up Study. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2021, 31, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Georges, M.; Hutting, N.; Hudon, A. Competencies for Physiotherapists Working to Facilitate Rehabilitation, Work Participation and Return to Work for Workers with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Scoping Review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2022, 32, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, P.; Pope, R.; Simas, V.; Canetti, E.; Schram, B.; Orr, R. The Effects of Early Physiotherapy Treatment on Musculoskeletal Injury Outcomes in Military Personnel: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoria, W. Early Intervention Physiotherapy Framework (EIPF). 2020. Available online: https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/early-intervention-physiotherapy-framework-eipf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Gosling, C.; Keating, J.; Iles, R.; Morgan, P.; Hopmans, R. Strategies to Enable Physiotherapists to Promote Timely Return to Work Following Injury. 2015. Available online: https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/strategies-to-enable-physiotherapists-to-promote-timely-return-to (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Awang, H.; Mansor, N. Predicting Employment Status of Injured Workers Following a Case Management Intervention. Saf. Health Work 2017, 9, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.; Maas, E.T.; Koehoorn, M.; McLeod, C. Time to return to work following workplace violence among direct healthcare and social workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorshidi, H.A.; Hassani-Mahmooei, B.; Haffari, G. An Interpretable Algorithm on Post-injury Health Service Utilization Patterns to Predict Injury Outcomes. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prang, K.H.; Hassani-Mahmooei, B.; Collie, A. Compensation Research Database: Population-based injury data for surveillance, linkage and mining. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stel, V.S.; Dekker, F.W.; Tripepi, G.; Zoccali, C.; Jager, K.J. Survival Analysis I: The Kaplan-Meier Method. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2011, 119, c83–c88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.C.; Fischer, F.M. Work ability and job survival: Four-year follow-up. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, A.K.C.M.; Tai, E.L.M.; Kueh, Y.C.; Siti-Azrin, A.H.; Noordin, Z.; Shatriah, I. Survival time of visual gains after diabetic vitrectomy and its relationship with ischemic heart disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damato, B.; Taktak, A. Chapter 2—Survival after Treatment of Intraocular Melanoma. In Outcome Prediction in Cancer; Taktak, A.F.G., Fisher, A.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Khorshidi, H.A.; Marembo, M.; Aickelin, U. Predictors of Return to Work for Occupational Rehabilitation Users in Work-Related Injury Insurance Claims: Insights from Mental Health. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2019, 29, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).