Best Practices for the Management of Patients with Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease According to a German Nationwide Analysis of Expert Centers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

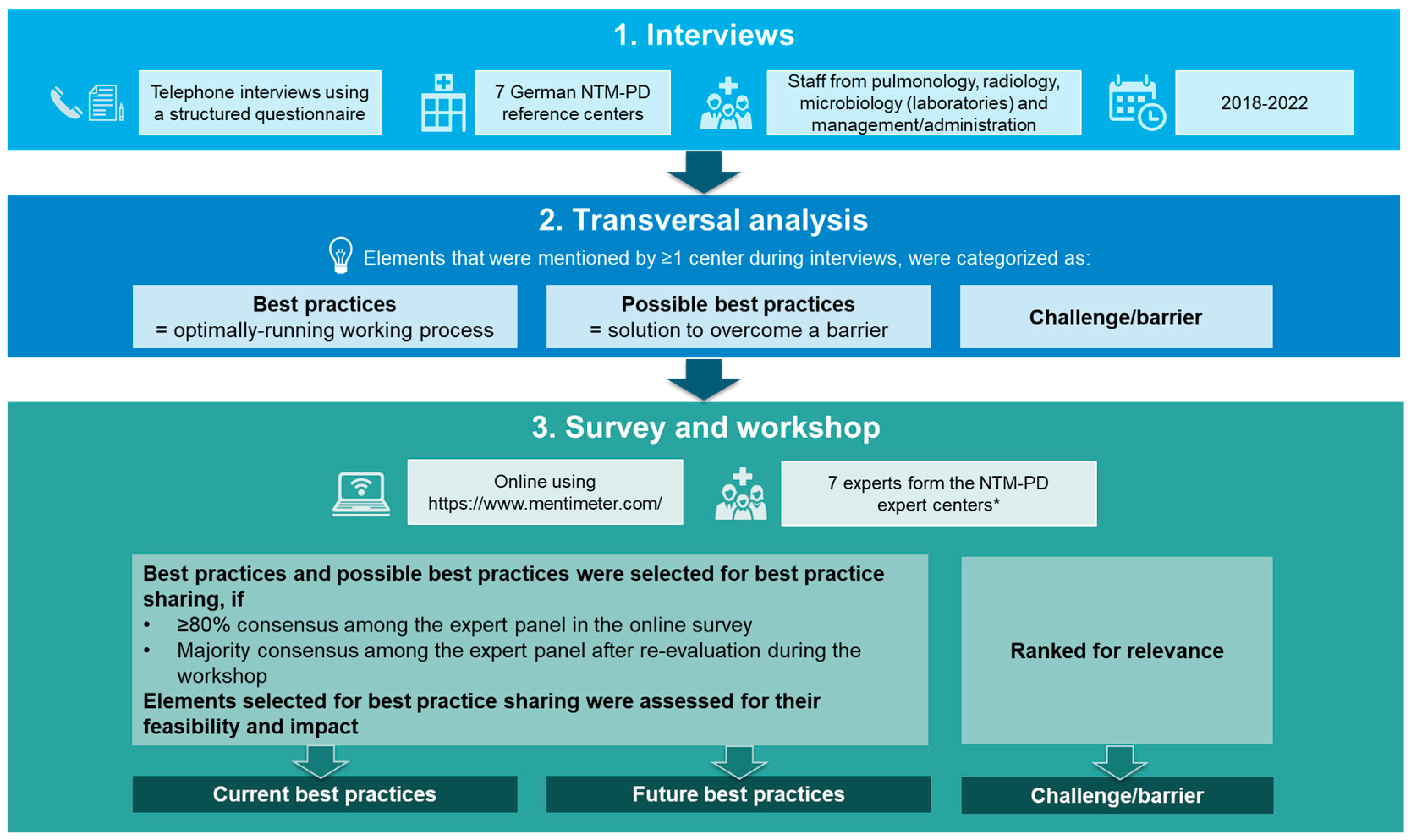

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Interviews

2.2. Transversal Analysis

2.3. Survey and Workshop for Expert Evaluation of Transversal Analysis Results

2.4. Data Reporting

3. Results

3.1. NTM-PD Expert Centers Overview

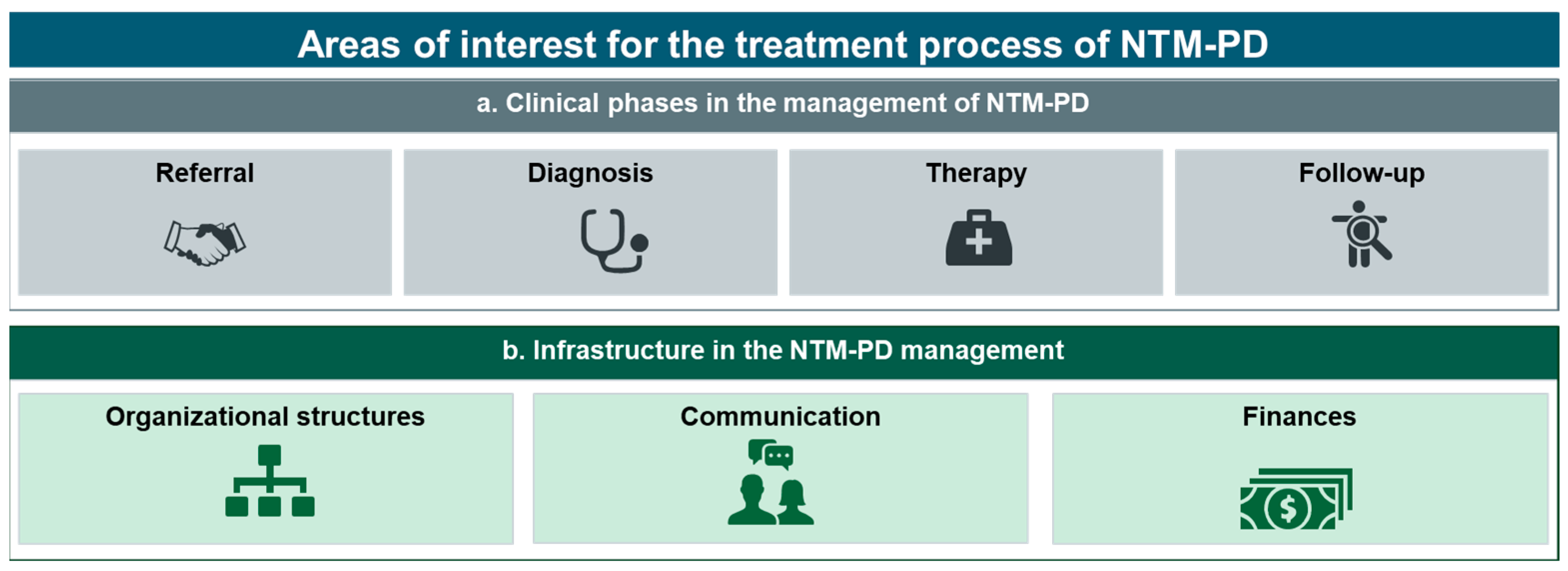

3.2. Transversal Analysis Results

3.3. Selection of Current and Future Best Practices

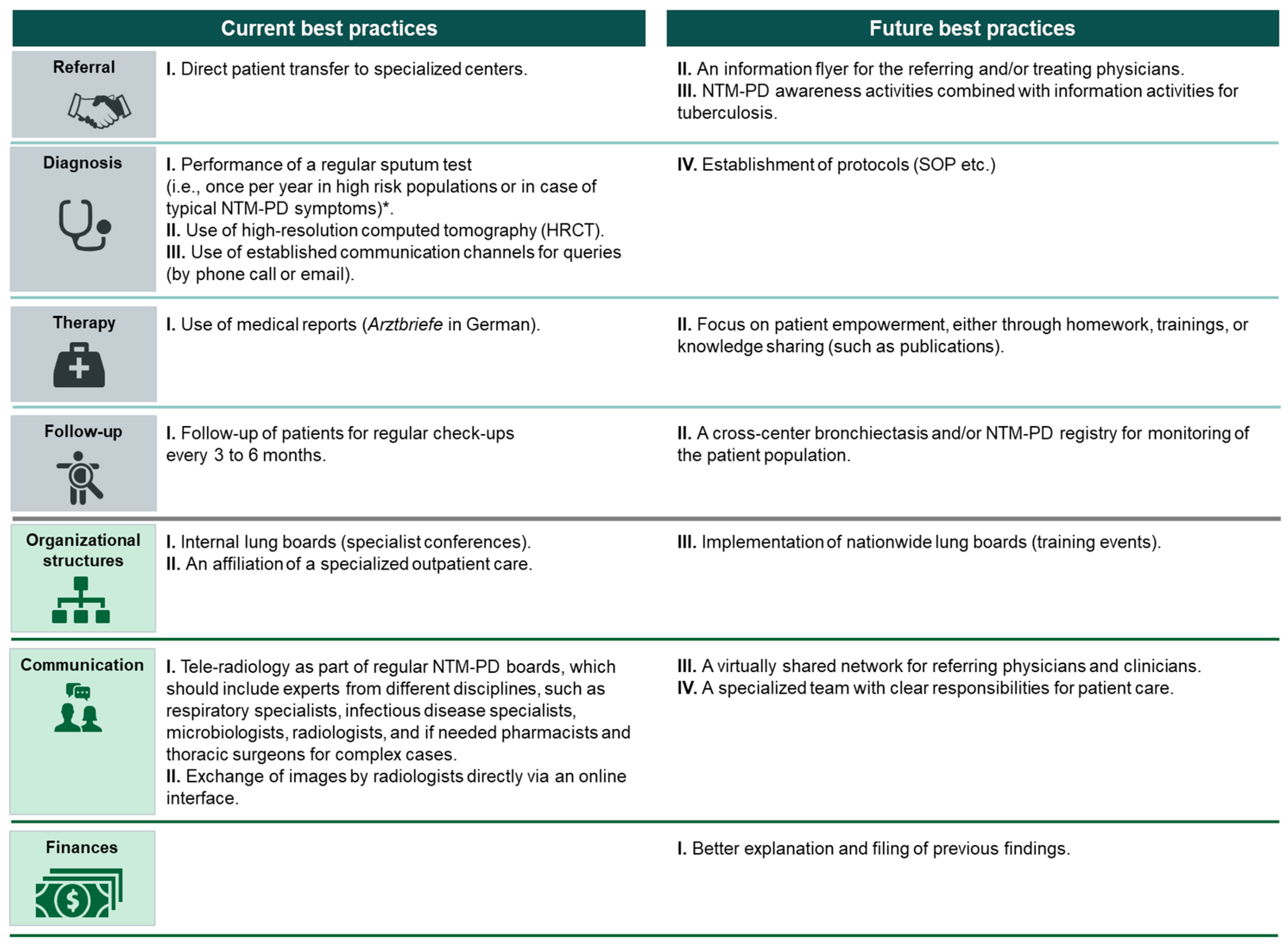

3.3.1. Clinical Phases in the Management of NTM-PD (a)

Referral

- Direct patient transfer to specialized centers.

- II.

- An information flyer for the referring and/or treating physicians.

- III.

- NTM-PD awareness activities combined with information activities for tuberculosis.

Diagnosis

- I.

- II.

- Use of HRCT imaging [6].

- III.

- Use of established communication channels for queries (by phone call or email).

- IV.

- Establishment of protocols (standard operating procedure, etc.).

Therapy

- I.

- Use of medical reports (Arztbriefe in German)

- II.

- Focus on patient empowerment, either through homework, training, or knowledge sharing (such as publications).

Follow-Up

- I.

- Follow-up of patients for regular check-ups every 3 to 6 months.

- II.

- A cross-center bronchiectasis and/or NTM-PD registry for monitoring of the patient population.

3.3.2. Infrastructure in the NTM-PD Management Process (b)

Organizational Structures

- I.

- Internal lung boards (specialist conferences).

- II.

- An affiliation of specialized outpatient care [24].

- III.

- Implementation of nationwide lung boards (training events).

Communication

- I.

- Tele-radiology as part of regular multidisciplinary NTM-PD boards, which should include experts from different disciplines, such as respiratory specialists, infectious disease specialists, microbiologists, radiologists, and, if needed, pharmacists and thoracic surgeons for complex cases.

- II.

- Exchange of images by radiologists directly via an online interface.

- III.

- A virtually shared network for referring physicians and clinicians.

- IV.

- A specialized team with clear responsibilities for patient care.

Finances

3.4. Challenges/Barriers in NTM-PD Management

3.4.1. Clinical Phases in NTM-PD Management (a)

3.4.2. Infrastructure for NTM-PD Management (b)

4. Discussion

4.1. Best Practices in the NTM-PD Management Process and Challenges Associated with Their Implementation

4.1.1. Best Practices during Patient Referral

4.1.2. Best Practice Diagnostics

4.1.3. Best Practices during Therapy

4.1.4. Best Practices during Follow-Up

4.1.5. Evaluating the Implementation of Best Practices

4.2. Study Limitations

4.3. Key Findings and Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falkinham, J.O., III. Surrounded by mycobacteria: Nontuberculous mycobacteria in the human environment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfeld, N.; Haas, W.; Richter, E.; Bauer, T.T.; Bös, L.; Castell, S.; Hauer, B.; Magdorf, K.; Matthiessen, W.; Mauch, H.; et al. Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie nichttuberkulöser Mykobakteriosen des Deutschen Zentralkomitees zur Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose (DZK) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin (DGP). Pneumologie 2013, 67, 605–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primm, T.P.; Lucero, C.A.; Falkinham, J.O., III. Health impacts of environmental mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ingen, J.; Bendien, S.A.; de Lange, W.C.; Hoefsloot, W.; Dekhuijzen, P.N.; Boeree, M.J.; van Soolingen, D. Clinical relevance of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated in the Nijmegen-Arnhem region, The Netherlands. Thorax 2009, 64, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gommans, E.P.; Even, P.; Linssen, C.F.; van Dessel, H.; van Haren, E.; de Vries, G.J.; Dingemans, A.M.; Kotz, D.; Rohde, G.G. Risk factors for mortality in patients with pulmonary infections with non-tuberculous mycobacteria: A retrospective cohort study. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, C.L.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lange, C.; Cambau, E.; Wallace, R.J.J.; Andrejak, C.; Böttger, E.C.; Brozek, J.; Griffith, D.E.; Guglielmetti, L.; et al. Treatment of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease: An Official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, e1–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkraut, J.A.; Gallagher, J.; Morimoto, K.; Lange, C.; Haworth, C.; Floto, R.A.; Hoefsloot, W.; Griffith, D.E.; Wagner, D.; Ingen, J.V. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in Europe and Japan by Delphi estimation. Respir. Med. 2020, 173, 106164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringshausen, F.C.; Wagner, D.; de Roux, A.; Diel, R.; Hohmann, D.; Hickstein, L.; Welte, T.; Rademacher, J. Prevalence of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease, Germany, 2009–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, T.K.; Chedore, P.; Ying, A.M.; Jamieson, F. Isolation prevalence of pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacteria in Ontario, 1997–2003. Thorax 2007, 62, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjemian, J.; Olivier, K.N.; Seitz, A.E.; Falkinham, J.O., 3rd; Holland, S.M.; Prevots, D.R. Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.E.; Aksamit, T.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Catanzaro, A.; Daley, C.; Gordin, F.; Holland, S.M.; Horsburgh, R.; Huitt, G.; Iademarco, M.F.; et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 367–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, E.P.; Leung, J.M.; Fowler, C.J.; Haney, C.; Hsu, A.P.; Chen, F.; Duggal, P.; Oler, A.J.; McCormack, R.; Podack, E.; et al. Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infection. A Multisystem, Multigenic Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, M.; Marras, T.K. Impaired health-related quality of life in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Respir. Med. 2011, 105, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diel, R.; Lipman, M.; Hoefsloot, W. High mortality in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.S.; Koh, W.J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringshausen, F.C.; Ewen, R.; Multmeier, J.; Monga, B.; Obradovic, M.; van der Laan, R.; Diel, R. Predictive modeling of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease epidemiology using German health claims data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, O.M.; van der Laan, R.; Obradovic, M.; McMahon, P.; Daniels, F.; Pitcher, A.; Loebinger, M.R. Identification of potentially undiagnosed patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease using machine learning applied to primary care data in the UK. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotilainen, H.; Valtonen, V.; Tukiainen, P.; Poussa, T.; Eskola, J.; Jarvinen, A. Clinical findings in relation to mortality in non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: Patients with Mycobacterium avium complex have better survival than patients with other mycobacteria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, M.; Cleverley, J.; Fardon, T.; Musaddaq, B.; Peckham, D.; van der Laan, R.; Whitaker, P.; White, J. Current and future management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) in the UK. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ingen, J.; Wagner, D.; Gallagher, J.; Morimoto, K.; Lange, C.; Haworth, C.S.; Floto, R.A.; Adjemian, J.; Prevots, D.R.; Griffith, D.E.; et al. Poor adherence to management guidelines in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1601855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, R.; Obradovic, M.; Tyler, S.; Engelhard, J.; Kostev, K. Real-world treatment patterns in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in general and pneumologist practices in Germany. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 2020, 20, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.; Gibson-Smith, K.; MacLure, K.; Mair, A.; Alonso, A.; Codina, C.; Cittadini, A.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Fleming, G.; Gennimata, D.; et al. A modified Delphi study to determine the level of consensus across the European Union on the structures, processes and desired outcomes of the management of polypharmacy in older people. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, R.; Gupta, A.; Herbert, C.; Payne, M.; Diaz-Mendoza, S.; Vincent, S.A.; Kovaleva, E. Delphi panel for consensus on the optimal management of dabrafenib plus trametinib-related pyrexia in patients with melanoma. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2022, 14, 17588359221127681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alliance, N.G. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. In Cystic Fibrosis: Diagnosis and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.B.; Fortescue, R.; Grimwood, K.; Alexopoulou, E.; Bell, L.; Boyd, J.; Bush, A.; Chalmers, J.D.; Hill, A.T.; Karadag, B.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of children and adolescents with bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2002990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G-BA. Richtlinie des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über die Ambulante Spezialfachärztliche Versorgung Nach § 116b SGB V. 2022. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/richtlinien/80/ (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Shteinberg, M.; Boyd, J.; Aliberti, S.; Polverino, E.; Harris, B.; Berg, T.; Posthumus, A.; Ruddy, T.; Goeminne, P.; Lloyd, E.; et al. What is important for people with nontuberculous mycobacterial disease? An EMBARC-ELF patient survey. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00807-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaddaq, B.; Cleverley, J.R. Diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD): Modern challenges. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENPADE. ENPADE Survey Results Summary. Available online: https://ntmpatientsurvey.eu (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Ironmonger, L.; Ohuma, E.; Ormiston-Smith, N.; Gildea, C.; Thomson, C.S.; Peake, M.D. An evaluation of the impact of large-scale interventions to raise public awareness of a lung cancer symptom. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, K.O. Nonpharmacological therapies for interstitial lung disease. Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2018, 7, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Center Borstel. Available online: https://fz-borstel.de/index.php/en/ (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- German Center for Infection Research. Available online: https://www.dzif.de/de (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Stronisch, A.; Mardian, S.; Florcken, A. Centralized and Interdisciplinary Therapy Management in the Treatment of Sarcomas. Life 2023, 13, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ORPHANET. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/index.php (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- SE-ATLAS. Available online: https://www.se-atlas.de/ (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Lenz, F.; Harms, L. The Impact of Patient Support Programs on Adherence to Disease-Modifying Therapies of Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis in Germany: A Non-Interventional, Prospective Study. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 2999–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, A.; Clewell, J.; Shillington, A.C. The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: A targeted systematic review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, M.; Schmidt, O.; Schultz, T.; Woehrle, H.; Sundrup, M.G.; Schöbel, C. Experiences with digital care of patients with chronic and acute lung diseases during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Internist 2022, 63, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederer, J.; Bolte, H.; FInk, C.; Tuengerthal, S.; Rehbock, B.; Hieckel, H.G.; Diederich, S.; Hofmann-Preiss, K.; Lörcher, U.; Heussel, C.P. Protocol Recommendations for Computed Tomography of the Lung: Consensus of the Chest Imaging Workshop of the German Radiologic Society. Fortschr Rontgenstr 2008, 180, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element No. | a. Clinical Phases in the Management of NTM-PD | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Referral | ||

| 1 |

| BP |

| 2 |

| PBP |

| 3 |

| PBP |

| Diagnosis | ||

| 4 |

| BP |

| 5 |

| BP |

| 6 |

| BP |

| 7 |

| PBP |

| Therapy | ||

| 8 |

| BP |

| 9 |

| PBP |

| 10 |

| BP |

| Follow-up | ||

| 11 |

| BP |

| 12 |

| PBP |

| b. Infrastructure in NTM-PD management | ||

| Organization structures | ||

| 13 |

| BP |

| 14 |

| BP |

| 15 |

| PBP |

| 16 |

| BP |

| 17 |

| BP |

| Communication | ||

| 18 |

| BP |

| 19 |

| BP |

| 20 |

| PBP |

| 21 |

| PBP |

| 22 |

| PBP |

| Finances | ||

| 23 |

| PBP |

| 24 |

| BP |

| Element No. | a. Clinical Phases in the Management of NTM-PD |

|---|---|

| Referral | |

| 1 | Limited experience of referring physician (including general physicians and respiratory specialists) with diagnosis and management of NTM-PD. |

| 2 | No specific request for investigation of NTM-PD infection during referral, leading to most patients being incidental findings. |

| 3 | Incomplete documentation of findings and result reports, leading to increased effort and complications. |

| 4 | Referral is only possible through a respiratory specialist, which can lead to extended waiting times. |

| Diagnosis | |

| 5 | Lack of time and staff to make diagnostic and treatment decisions, as the disease is individual and complex. |

| Follow-up | |

| 6 | Time-consuming regular feedback with the referring physician. |

| 7 | Lack of adherence to guideline-based therapies and possibly also to specified therapy plans. |

| b. Infrastructure in NTM-PD management | |

| Communication | |

| 8 | Lack of a suitable external communication channel for the exchange of patient data, findings, and diagnoses. |

| Finances | |

| 9 | Complex and time-consuming processes for services billed both in the inpatient and outpatient setting, which can lead to mistakes. |

| 10 | Almost no in-house expertise available for billing via a uniform evaluation standard (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab in German) despite a very complicated system. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rohde, G.; Eichinger, M.; Gläser, S.; Heiß-Neumann, M.; Kehrmann, J.; Neurohr, C.; Obradovic, M.; Kröger-Kilian, T.; Loebel, T.; Taube, C. Best Practices for the Management of Patients with Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease According to a German Nationwide Analysis of Expert Centers. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192610

Rohde G, Eichinger M, Gläser S, Heiß-Neumann M, Kehrmann J, Neurohr C, Obradovic M, Kröger-Kilian T, Loebel T, Taube C. Best Practices for the Management of Patients with Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease According to a German Nationwide Analysis of Expert Centers. Healthcare. 2023; 11(19):2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192610

Chicago/Turabian StyleRohde, Gernot, Monika Eichinger, Sven Gläser, Marion Heiß-Neumann, Jan Kehrmann, Claus Neurohr, Marko Obradovic, Tim Kröger-Kilian, Tobias Loebel, and Christian Taube. 2023. "Best Practices for the Management of Patients with Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease According to a German Nationwide Analysis of Expert Centers" Healthcare 11, no. 19: 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192610