Assessment of the Impact of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Ethics Statement

2.2. Measurement Scale

WHOQOL-BREF and LURN Scale

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fragala, E.; Russo, G.; Di Rosa, A.; Giardina, R.; Privitera, S.; Favilla, V.; Castelli, T.; Chisari, M.; Caramma, A.; Patti, F. Relationship between urodynamic findings and sexual function in multiple sclerosis patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, R. Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction in multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, and related disorders. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centonze, D.; Petta, F.; Versace, V.; Rossi, S.; Torelli, F.; Prosperetti, C.; Rossi, S.; Marfia, G.; Bernardi, G.; Koch, G. Effects of motor cortex rTMS on lower urinary tract dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2007, 13, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragalà, E.; Russo, G.I.; Di Rosa, A.; Giardina, R.; Privitera, S.; Favilla, V.; Patti, F.; Welk, B.; Cimino, S.; Castelli, T. Association between the neurogenic bladder symptom score and urodynamic examination in multiple sclerosis patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Int. Neurourol. J. 2015, 19, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Polo, J.; Adot, J.M.; Allué, M.; Arlandis, S.; Blasco, P.; Casanova, B.; Matías-Guiu, J.; Madurga, B.; Meza-Murillo, E.R.; Müller-Arteaga, C. Consensus document on the multidisciplinary management of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2020, 39, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, P.K.; Sand, R.I. The diagnosis and management of lower urinary tract symptoms in multiple sclerosis patients. Dis. Mon. 2013, 59, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dandan, H.B.; Galvin, R.; McClurg, D.; Coote, S.; Robinson, K. Management strategies for neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: A qualitative study of the experiences of people with multiple sclerosis and healthcare professionals. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 3805–3815. [Google Scholar]

- Akkoc, Y.; Karapolat, H.; Eyigor, S.; Yesil, H.; Yüceyar, N. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients with urinary disorders: Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of King’s Health Questionnaire. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornic, J.; Panicker, J.N. The Management of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonniaud, V.; Parratte, B.; Amarenco, G.; Jackowski, D.; Didier, J.-P.; Guyatt, G. Measuring quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients with urinary disorders using the Qualiveen questionnaire. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciudin, A.; Franco, A.; Diaconu, M.G.; Peri, L.; Vivas, V.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Alcaraz, A. Quality of life of multiple sclerosis patients: Translation and validation of the Spanish version of Qualiveen. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2012, 31, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, C. Overview on the lower urinary tract. In Urinary Tract; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Panicker, J.N.; Fowler, C.J.; Kessler, T.M. Lower urinary tract dysfunction in the neurological patient: Clinical assessment and management. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, B.J.; Stephens, D.S. Urinary tract infection: An overview. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1997, 314, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bragadin, M.M.; Motta, R.; Uccelli, M.M.; Tacchino, A.; Ponzio, M.; Podda, J.; Konrad, G.; Rinaldi, S.; Della Cava, M.; Battaglia, M.A. Lower urinary tract dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis: A post-void residual analysis of 501 cases. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 45, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.A.; Mak, R.H. Urinary tract infection in pediatrics: An overview. J. Pediatr. 2020, 96, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Porru, D.; Campus, G.; Garau, A.; Sorgia, M.; Pau, A.; Spinici, G.; Pischedda, M.; Marrosu, M.; Scarpa, R.; Usai, E. Urinary tract dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: Is there a relation with disease-related parameters? Spinal Cord 1997, 35, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.S.; Smith, A.L. Questionnaires to Evaluate Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men and Women. Curr. Bladder Dysfunct. Rep. 2021, 16, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulum, B.; Özçakar, Z.B.; Kavaz, A.; Hüseynova, M.; Ekim, M.; Yalçınkaya, F. Lower urinary tract dysfunction is frequently seen in urinary tract infections in children and is often associated with reduced quality of life. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, e454–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenlehner, F.; Wullt, B.; Ballarini, S.; Zingg, D.; Naber, K.G. Social and economic burden of recurrent urinary tract infections and quality of life: A patient web-based study (GESPRIT). Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2018, 18, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, M.Q. Evaluation of Health-Related Quality of Life in Women with Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections Using the EQ-5D-3L in Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 2419–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomeroy, I.; Tennant, A.; Mills, R.; Group, T.S.; Young, C. The WHOQOL-BREF: A modern psychometric evaluation of its internal construct validity in people with multiple sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Smith, A.R.; Griffith, J.W.; Flynn, K.E.; Bradley, C.S.; Gillespie, B.W.; Kirkali, Z.; Talaty, P.; Jelovsek, J.E.; Helfand, B.T. A new outcome measure for LUTS: Symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network symptom Index-29 (LURN SI-29) questionnaire. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Marijam, A.; Mitrani-Gold, F.S.; Wright, J.; Joshi, A.V. Activity impairment, health-related quality of life, productivity, and self-reported resource use and associated costs of uncomplicated urinary tract infection among women in the United States. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0277728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippova, E.S.; Bazhenov, I.V.; Ziryanov, A.V.; Moskvina, E.Y. Evaluation of lower urinary tract dysfunction impact on quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: Russian translation and validation of SF-Qualiveen. Mult. Scler. Int. 2020, 2020, 4652439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucio, A.C.; Perissinoto, M.C.; Natalin, R.A.; Prudente, A.; Damasceno, B.P.; D’ancona, C.A.L. A comparative study of pelvic floor muscle training in women with multiple sclerosis: Its impact on lower urinary tract symptoms and quality of life. Clinics 2011, 66, 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.L.; Chen, J.; Wyman, J.F.; Newman, D.K.; Berry, A.; Schmitz, K.; Stapleton, A.E.; Klusaritz, H.; Lin, G.; Stambakio, H. Survey of lower urinary tract symptoms in United States women using the new lower urinary tract dysfunction research Network-Symptom Index 29 (LURN-SI-29) and a national research registry. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2022, 41, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, R.C.; Ryan, S.T. Diagnosis and management of lower urinary tract dysfunction. Surg. Clin. 2016, 96, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖZEN, Ş.; POLAT, Ü. Bladder training and Kegel exercises on urinary symptoms in female patients with multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 2023, 17, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peco-Antić, A.; Miloševski-Lomić, G. Development of the lower urinary tract and its functional disorders. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2015, 143, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Gender | Participants (428) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (270, 63.1%) | Males (158, 36.9%) | ||||||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | ||

| Age | Less than 20 | 9 | 2.1% | 1 | 0.2% | 10 | 2.3% |

| 20–30 | 103 | 24.1% | 51 | 11.9% | 154 | 36.0% | |

| 31–40 | 94 | 22.0% | 62 | 14.5% | 156 | 36.4% | |

| 41–50 | 53 | 12.4% | 37 | 8.6% | 90 | 21.0% | |

| Older than 50 | 11 | 2.6% | 7 | 1.6% | 18 | 4.2% | |

| Educational level | High school | 46 | 10.7% | 41 | 9.6% | 87 | 20.3% |

| Illiterate | 2 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.7% | |

| Secondary school | 14 | 3.3% | 5 | 1.2% | 19 | 4.4% | |

| University | 208 | 48.6% | 111 | 25.9% | 319 | 74.5% | |

| Marital status | Divorced | 26 | 6.1% | 7 | 1.6% | 33 | 7.7% |

| Married | 120 | 28.0% | 84 | 19.6% | 204 | 47.7% | |

| Single | 123 | 28.7% | 67 | 15.7% | 190 | 44.4% | |

| Widow | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Occupation | Homemaker | 99 | 23.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 99 | 23.1% |

| Retired | 12 | 2.8% | 24 | 5.6% | 36 | 8.4% | |

| Student | 34 | 7.9% | 18 | 4.2% | 52 | 12.1% | |

| Teacher | 25 | 5.8% | 14 | 3.3% | 39 | 9.1% | |

| Other | 100 | 23.1% | 102 | 23.8% | 201 | 47.0% | |

| MS type | Primary Progressive | 27 | 6.3% | 9 | 2.1% | 36 | 8.4% |

| Relapsing–Remitting | 78 | 18.2% | 44 | 10.3% | 122 | 28.5% | |

| Secondary Progressive | 7 | 1.6% | 17 | 4.0% | 24 | 5.6% | |

| Unknown | 158 | 36.9% | 88 | 20.6% | 246 | 57.5% | |

| Family history of MS | No | 230 | 53.7% | 136 | 31.8% | 366 | 85.5% |

| Yes | 40 | 9.3% | 22 | 5.1% | 62 | 14.5% | |

| Questionnaire | Frequency | Patients | Gender | p-Value * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | |||||||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | |||

| Q9. In the past 7 days, how often did you have pain or discomfort while urinating? | never | 204 | 47.70% | 143 | 53.00% | 61 | 38.60% | 0.000326 |

| a few times | 132 | 30.80% | 87 | 32.20% | 45 | 28.50% | ||

| about half the time | 38 | 8.90% | 15 | 5.60% | 23 | 14.60% | ||

| most of the time | 34 | 7.90% | 17 | 6.30% | 17 | 10.80% | ||

| every time | 20 | 4.70% | 8 | 3.00% | 12 | 7.60% | ||

| Q10. In the past 7 days, how often did you have pain or discomfort right after you had finished urinating? | never | 250 | 58.40% | 171 | 63.30% | 79 | 50.00% | 0.033 |

| a few times | 97 | 22.70% | 59 | 21.90% | 38 | 24.10% | ||

| about half the time | 32 | 7.50% | 14 | 5.20% | 18 | 11.40% | ||

| most of the time | 34 | 7.90% | 18 | 6.70% | 16 | 10.10% | ||

| every time | 15 | 3.50% | 8 | 3.00% | 7 | 4.40% | ||

| Q12. In the past 7 days, how often did you have a delay before you started to urinate? | never | 175 | 40.90% | 133 | 49.30% | 42 | 26.60% | 0.00004 |

| a few times | 141 | 32.90% | 84 | 31.10% | 57 | 36.10% | ||

| about half the time | 40 | 9.30% | 20 | 7.40% | 20 | 12.70% | ||

| most of the time | 49 | 11.40% | 23 | 8.50% | 26 | 16.50% | ||

| every time | 23 | 5.40% | 10 | 3.70% | 13 | 8.20% | ||

| Q13. In the past 7 days, once you started urinating, how often did your urine flow stop and start again? | never | 183 | 42.80% | 128 | 47.40% | 55 | 34.80% | 0.000301 |

| a few times | 134 | 31.30% | 84 | 31.10% | 50 | 31.60% | ||

| about half the time | 45 | 10.50% | 32 | 11.90% | 13 | 8.20% | ||

| most of the time | 43 | 10.00% | 16 | 5.90% | 27 | 17.10% | ||

| every time | 23 | 5.40% | 10 | 3.70% | 13 | 8.20% | ||

| Q14. In the past 7 days, how often was your urine flow slow or weak? | never | 165 | 38.60% | 115 | 42.60% | 50 | 31.60% | 0.003 |

| a few times | 147 | 34.30% | 99 | 36.70% | 48 | 30.40% | ||

| about half the time | 50 | 11.70% | 26 | 9.60% | 24 | 15.20% | ||

| most of the time | 39 | 9.10% | 19 | 7.00% | 20 | 12.70% | ||

| every time | 27 | 6.30% | 11 | 4.10% | 16 | 10.10% | ||

| Q.15 In the past 7 days, how often did you have a trickle or dribble at the end of your urine flow? | never | 143 | 33.40% | 106 | 39.30% | 37 | 23.40% | 0.000096 |

| a few times | 131 | 30.60% | 85 | 31.50% | 46 | 29.10% | ||

| about half the time | 48 | 11.20% | 30 | 11.10% | 18 | 11.40% | ||

| most of the time | 59 | 13.80% | 23 | 8.50% | 36 | 22.80% | ||

| every time | 47 | 11.00% | 26 | 9.60% | 21 | 13.30% | ||

| Q16. In the past 7 days, how often did you feel a sudden need to urinate? | never | 124 | 29.00% | 90 | 33.30% | 34 | 21.50% | 0.003 |

| a few times | 93 | 21.70% | 66 | 24.40% | 27 | 17.10% | ||

| about half the time | 105 | 24.50% | 53 | 19.60% | 52 | 32.90% | ||

| most of the time | 72 | 16.80% | 40 | 14.80% | 32 | 20.30% | ||

| every time | 34 | 7.90% | 21 | 7.80% | 13 | 8.20% | ||

| Q25. In the past 7 days, how often did you feel that your bladder was not completely empty after urination? | never | 120 | 28.00% | 64 | 23.70% | 57 | 36.10% | 0.008 |

| a few times | 182 | 42.50% | 116 | 43.00% | 66 | 41.80% | ||

| about half the time | 39 | 9.30% | 23 | 8.50% | 16 | 10.10% | ||

| most of the time | 58 | 13.70% | 43 | 15.90% | 15 | 9.50% | ||

| every time | 28 | 6.50% | 24 | 8.90% | 4 | 2.50% | ||

| Q26. In the past 7 days, how often did you dribble urine just after zipping your pants or pulling up your underwear? | never | 238 | 55.60% | 148 | 54.80% | 90 | 57.00% | 2.04 × 10−7 |

| a few times | 123 | 28.70% | 74 | 27.40% | 49 | 31.00% | ||

| about half the time | 28 | 6.50% | 15 | 5.60% | 13 | 8.20% | ||

| most of the time | 26 | 6.10% | 24 | 8.90% | 2 | 1.30% | ||

| every time | 13 | 3.00% | 9 | 3.30% | 4 | 2.50% | ||

| Q28. In the past 7 days, how bothered were you by urinary symptoms? | Not at all bothered | 123 | 28.70% | 76 | 28.10% | 47 | 29.70% | 0.041 |

| Somewhat bothered | 183 | 42.80% | 106 | 39.30% | 77 | 48.70% | ||

| Very bothered | 59 | 13.80% | 39 | 14.40% | 20 | 12.70% | ||

| Extremely bothered | 63 | 14.70% | 49 | 18.10% | 14 | 8.90% | ||

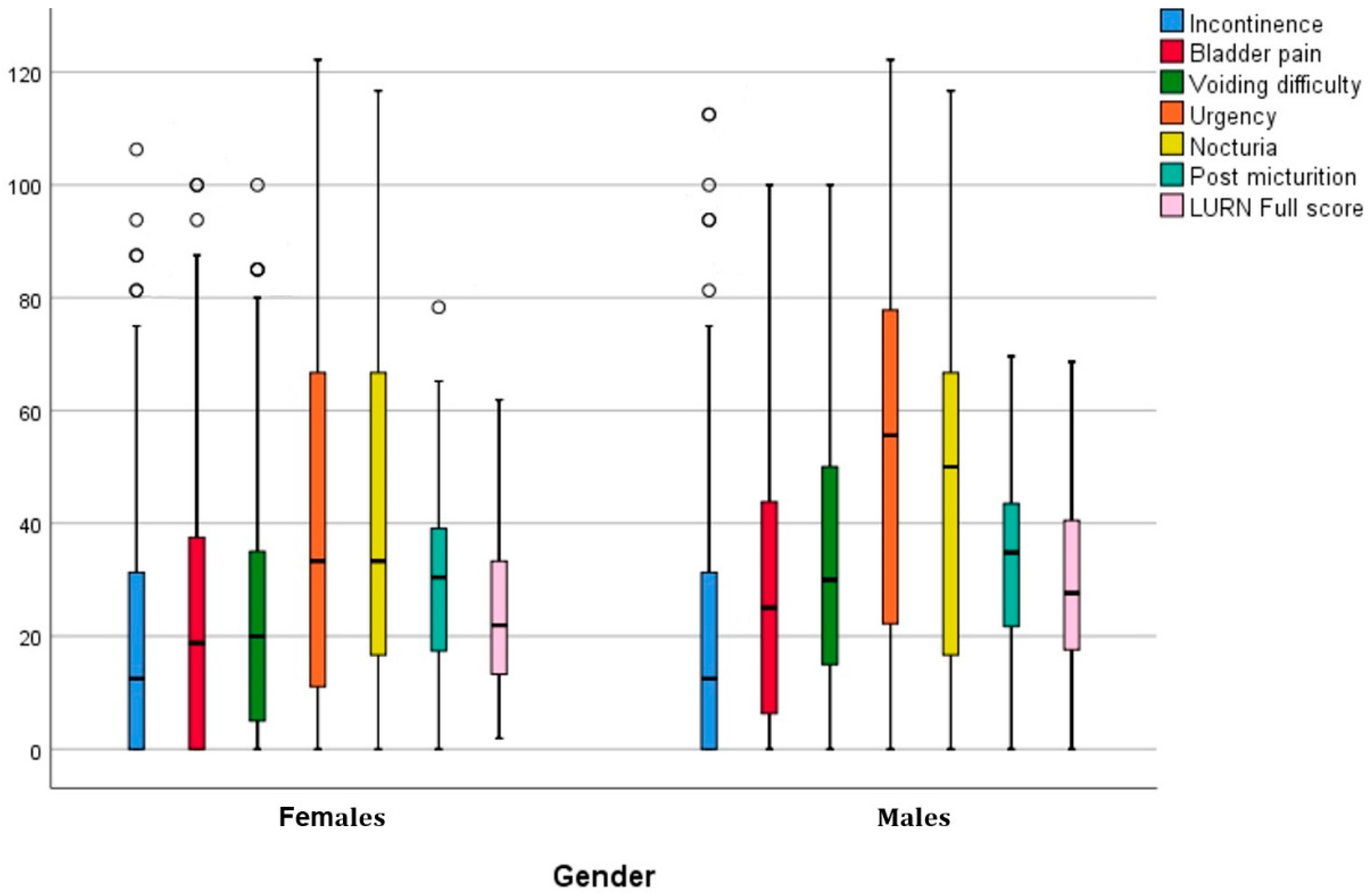

| Section | Patients | Gender | p-Value * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (270) | Males (158) | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Section A | Incontinence | 22.80 | 26.80 | 21.75 | 26.23 | 24.58 | 27.76 | 0.2920 |

| Section B | Bladder pain | 26.05 | 25.64 | 23.58 | 24.59 | 30.28 | 26.89 | 0.0090 |

| Section C | Voiding difficulty | 28.40 | 24.59 | 24.13 | 22.49 | 35.70 | 26.32 | 0.0000 |

| Section D | Urgency | 47.20 | 36.88 | 43.54 | 36.68 | 53.45 | 36.51 | 0.0070 |

| Section E | Nocturia | 44.74 | 32.91 | 42.96 | 31.72 | 47.79 | 34.75 | 0.1430 |

| Section F | Post micturition | 31.16 | 15.95 | 29.39 | 14.87 | 34.17 | 17.26 | 0.0003 |

| Full score | 27.37 | 16.62 | 25.29 | 15.54 | 30.91 | 17.80 | 0.0010 | |

| Questionnaire | Frequency | Patients | Gender | p-Value * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | |||||||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | |||

| Q1. How would you rate your quality of life? | Very poor | 15 | 3.5% | 9 | 3.3% | 6 | 3.8% | |

| Poor | 38 | 8.9% | 23 | 8.5% | 15 | 9.5% | ||

| Neither poor nor good | 186 | 43.5% | 104 | 38.5% | 82 | 51.9% | 0.043 | |

| Good | 132 | 30.8% | 96 | 35.6% | 36 | 22.8% | ||

| Very good | 57 | 13.3% | 38 | 14.1% | 19 | 12.0% | ||

| Q4. How much do you need any medical treatment to functionin your daily life? | Not at all | 67 | 15.7% | 36 | 13.3% | 31 | 19.6% | |

| A little | 69 | 16.1% | 33 | 12.2% | 36 | 22.8% | ||

| A moderate amount | 136 | 31.8% | 91 | 33.7% | 45 | 28.5% | 0.007 | |

| Very much | 24 | 5.6% | 17 | 6.3% | 7 | 4.4% | ||

| An extreme amount | 132 | 30.8% | 93 | 34.4% | 39 | 24.7% | ||

| Q13. How available to you is the information that you need in your day-to-day life? | Not at all | 33 | 7.7% | 21 | 7.8% | 12 | 7.6% | |

| A little | 83 | 19.4% | 41 | 15.2% | 42 | 26.6% | ||

| Moderately | 112 | 26.2% | 78 | 28.9% | 34 | 21.5% | 0.038 | |

| Mostly | 107 | 25.0% | 66 | 24.4% | 41 | 25.9% | ||

| Completely | 93 | 21.7% | 64 | 23.7% | 290 | 18.4% | ||

| Q15. How well are you able to get around? | Very poor | 32 | 7.5% | 19 | 7.0% | 13 | 8.2% | |

| Poor | 50 | 11.7% | 24 | 8.9% | 26 | 16.5% | ||

| Neither poor nor good | 90 | 21.0% | 48 | 17.8% | 42 | 26.6% | 0.008 | |

| Good | 116 | 27.1% | 81 | 30.0% | 35 | 22.2% | ||

| Very good | 140 | 32.7% | 98 | 36.3% | 42 | 26.6% | ||

| Q21. How satisfied are you with your sex life? | Very dissatisfied | 70 | 16.4% | 38 | 14.1% | 32 | 20.3% | |

| Dissatisfied | 70 | 16.4% | 34 | 12.6% | 36 | 22.8% | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 126 | 29.4% | 80 | 29.6% | 46 | 29.1% | 0.002 | |

| Satisfied | 108 | 25.2% | 82 | 30.4% | 26 | 16.5% | ||

| Very satisfied | 54 | 12.6% | 36 | 13.3% | 18 | 11.4% | ||

| Q22. How satisfied are you with the support you get from your friends? | Very dissatisfied | 72 | 16.8% | 47 | 17.4% | 25 | 15.8% | |

| Dissatisfied | 58 | 13.6% | 35 | 13.0% | 23 | 14.6% | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 107 | 25.0% | 54 | 20.0% | 53 | 33.5% | 0.011 | |

| Satisfied | 113 | 26.4% | 83 | 30.7% | 30 | 19.0% | ||

| Very satisfied | 78 | 18.2% | 51 | 18.9% | 27 | 17.1% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, M.A.; Amer, K.A.; Aldosari, A.A.S.; Al Qahtani, R.F.; Shar, H.S.; Al-Tarish, L.M.; Shawkhan, R.A.; Alahmadi, M.A.; Alsaleem, M.A.; AL-Eitan, L.N. Assessment of the Impact of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192694

Alghamdi MA, Amer KA, Aldosari AAS, Al Qahtani RF, Shar HS, Al-Tarish LM, Shawkhan RA, Alahmadi MA, Alsaleem MA, AL-Eitan LN. Assessment of the Impact of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(19):2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192694

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Mansour Abdullah, Khaled Abdulwahab Amer, Abdulrahman Ali S. Aldosari, Reemah Farhan Al Qahtani, Haneen Saeed Shar, Lujane Mohammed Al-Tarish, Rammas Abdullah Shawkhan, Mohammad Ali Alahmadi, Mohammed Abadi Alsaleem, and Laith Naser AL-Eitan. 2023. "Assessment of the Impact of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients in Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 11, no. 19: 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192694