Development, Objectives and Operation of Return-of-Service Bursary Schemes as an Investment to Build Health Workforce Capacity in South Africa: A Multi-Methods Study

Highlights

- Bursaries and scholarships have been used for many years by South Africa’s provinces to increase the number of health professionals in rural health facilities by funding individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds. However, their origins, implementation and impact on the health system are not well understood.

- The effectiveness of RoS schemes is being limited by poor implementation.

- There is poor documentation of policies, limited use of historical successes and failures of previous policy documents, poor planning, poor archiving and record keeping, and the selection of beneficiaries does not always promote equity.

- Policy implementers operate in isolation at different stages of the implementation process.

- Given these shortcomings, it is hard to assess the value of these schemes relative to other potential workforce investments.

- To overcome these shortcomings, we propose long-term workforce planning for these schemes: planning must be supported by evidence and accompanied by thorough risk assessments and plans for ongoing evaluation; policies must be documented in a structured way with a known review period; and institutional mechanisms for synergy, coordination, monitoring and archiving should be strengthened.

Abstract

1. Background

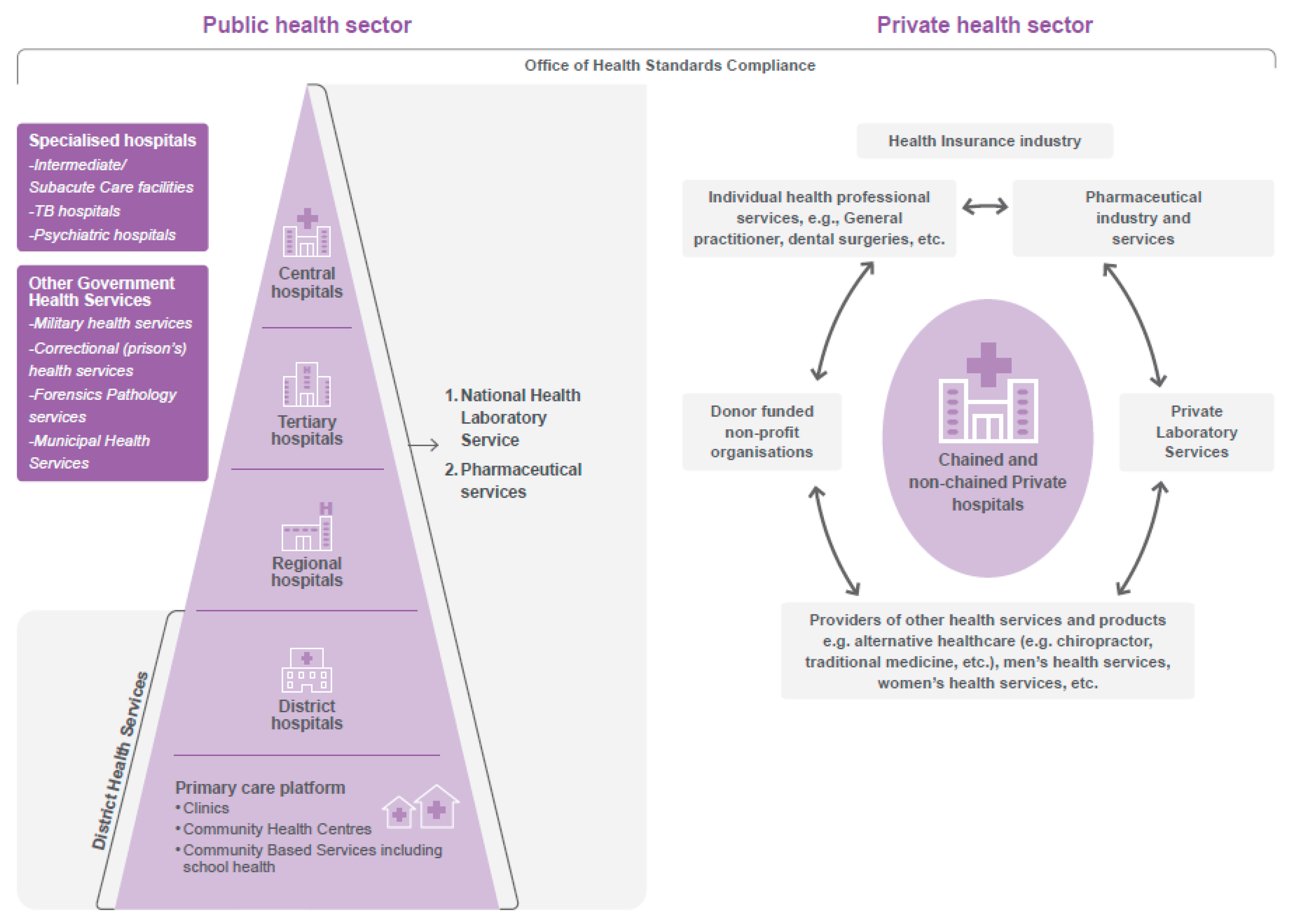

2. Context

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

3.2.1. Literature Review

3.2.2. In-Depth Interviews with Key Policymakers

3.2.3. Policy Review

3.3. Reflexivity

4. Data Analysis

5. Results

Document Availability, Archiving and Structure

6. Understanding RoS Schemes in South Africa (Context and Content)

6.1. Historical Recognition of Health Worker Shortage and Training Plans

6.2. Origins of RoS Schemes

6.3. Types of RoS Schemes Operating in South Africa

6.4. Justification for State-Funded Educational Initiative Policies

- (a)

- Continuity

- (b)

- Recruitment and retention

- (c)

- Social responsiveness to the needs of disadvantaged groups

- (d)

- Compliance with legislation and government mandates

- (e)

- Political reasons

6.5. Who Are RoS Beneficiaries and What Academic Programmes Are Supported by RoS Schemes?

6.6. Targeted Recruitment of Beneficiaries Who Are Likely to Address Health Worker Shortages

6.7. Noted Shortcomings in Beneficiary Selection

6.8. What Are the Obligations of Beneficiaries?

6.9. Is There Room for Contract Variation?

6.10. Funding Model

6.11. Use of Policy Development Framework

6.12. Policy Governance and Administration

6.13. Presence of Reasons for Review of Preceding Policy Document in Subsequent Versions

7. Process and Actors for Implementation of RoS Policies in South Africa

7.1. How Do RoS Schemes Operate in Practice?

7.2. How Does the Policy Planning and Implementation Process Work in Practice?

7.3. How Are the Opportunities Advertised?

7.4. How Are Beneficiaries Selected?

7.5. Where Do Beneficiaries Serve Their Contractual Obligation and How Is this Determination Made?

7.6. How Are the Databases Organised?

7.7. How Are Beneficiaries Recruited into Service?

7.8. What Are the Plans in Place to Strengthen the Policies?

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EC | Eastern Cape province |

| FS | Free State province |

| GP | Gauteng province |

| HPCSA | Health Professions Council of South Africa |

| HRD | Human Resource Development |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| ICSP | Internship and Community Service Programme |

| KZN | KwaZulu Natal province |

| LP | Limpopo province |

| MP | Mpumalanga province |

| NC | Northern Cape province |

| NHI | National Health Insurance |

| NW | North West province |

| RoS | Return-of-service |

| SAPC | South African Pharmacy Council |

| WC | Western Cape province |

References

- Grobler, L.; Marais, B.J.; Mabunda, S. Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, Cd005314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, U.; Dieleman, M.; Martineau, T. Staffing remote rural areas in middle- and low-income countries: A literature review of attraction and retention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabunda, S.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R.; Durbach, A. Evaluation of the alignment of policies and practices for state-sponsored educational initiatives for sustainable health workforce solutions in selected Southern African countries: A protocol, multimethods study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabunda, S.A.; Angell, B.; Yakubu, K.; Durbach, A.; Joshi, R. Reformulation and strengthening of return-of-service (ROS) schemes could change the narrative on global health workforce distribution and shortages in sub-Saharan Africa. Fam. Med. Community Health J. 2020, 8, e000498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Health Workforce Statistics, OECD, Supplemented by Country Data. 2020. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.NUMW.P3?locations=BW-SZ-LS-NA-ZA-ZG (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2019: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1237162/retrieve (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Mabunda, S.A.; Durbach, A.; Chitha, W.W.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R. Are return-of-service bursaries an effective investment to build health workforce capacity? A qualitative study of key South African policymakers. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, F.; Sarasa, N.L.; Cañizares, O.; Huguet, Y. Assessment of a complementary curricular strategy for training South African physicians in a Cuban medical university. MEDICC Rev. 2012, 14, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokitimi, S.; Schneider, M.; de Vries, P.J. Child and adolescent mental health policy in South Africa: History, current policy development and implementation, and policy analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pas, R.; Kolie, D.; Delamou, A.; Van Damme, W. Health workforce development and retention in Guinea: A policy analysis post-Ebola. Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovo, S. Analyzing the welfare-improving potential of land in the former homelands of South Africa. Agric. Econ. 2014, 45, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, T.; Hattingh, P.S. Black Homelands in South Africa; Africa Institute of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of South Africa. National Health Act: No. 61 of 2003, Government Gazette Number 26595; Republic of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2004; Volume 469. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a61-03.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- South African National Department of Health. White Paper for the Transformation of the Health System in South Africa; Government Gazette; South African National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 1997; Volume 667. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/17910gen6670.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Govan, P. National Health Act, 2003—Licence to practice—A step in the right direction? SADJ 2004, 59, 313–336. [Google Scholar]

- South African Government. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996: As Adopted on 8 May 1996 and Amended on 11 October 1996 by the Constitutional Assembly. Available online: https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/saconstitution-web-eng.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- South African National Department of Health (NDoH). 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy: Investing in the Health Workforce for Universal Health Coverage; Government Printers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020; Available online: https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2030-HRH-strategy-19-3-2020.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Harris, B.; Goudge, J.; Ataguba, J.E.; McIntyre, D.; Nxumalo, N.; Jikwana, S.; Chersich, M. Inequities in access to health care in South Africa. J. Public Health Policy 2011, 32 (Suppl. S1), S102–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African National Department of Health. Policy Framework and Strategy for Ward-Based Primary Healthcare Outreach Teams 2018/2019-2023/24; Government Printers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018; Available online: https://rhap.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Policy-WBPHCOT-4-April-2018-1.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Roos, E.L. Provincial Equitable Share Allocations in South Africa. Melbourne, Australia: Victoria University, Centre of Policy Studies/IMPACT Centre. 2020. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/cop/wpaper/g-298.html#:~:text=The%20provincial%20equitable%20share%20(PES,revenue%20to%20the%20nine%20provinces (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Reid, S.J. Compulsory community service for doctors in South Africa—An evaluation of the first year. S. Afr. Med. J. 2001, 91, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.J.; Peacocke, J.; Kornik, S.; Wolvaardt, G. Compulsory community service for doctors in South Africa: A 15-year review. S. Afr. Med. J. 2018, 108, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.; MacLeod, A.; Ellaway, R.H. CARDA: Guiding document analyses in health professions education research. Med. Educ. 2022, 57, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walt, G.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabunda, S.A.; Durbach, A.; Chitha, W.W.; Moaletsane, O.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R. How Were Return-of-Service Schemes Developed and Implemented in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho? Healthcare 2023, 11, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, C. Doctor shortages: Unpacking the ‘Cuban solution’. S. Afr. Med. J. 2013, 103, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, C. An inside view: A Cuban trainee’s journey. S. Afr. Med. J. 2013, 103, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donda, B.M.; Hift, R.J.; Singaram, V.S. Assimilating South African medical students trained in Cuba into the South African medical education system: Reflections from an identity perspective. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motala, M.; Van Wyk, J. Where are they working? A case study of twenty Cuban-trained South African doctors. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motala, M.; Van Wyk, J.M. Professional experiences in the transition of Cuban-trained South African medical graduates. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2021, 63, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncayiyana, D. Impact Assessment Study Report: RSA-CUBA Medical Training Program; Benguela Health: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2008; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Squires, N.; Colville, S.E.; Chalkidou, K.; Ebrahim, S. Medical training for universal health coverage: A review of Cuba-South Africa collaboration. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Reddy, P.; Nyembezi, A.; Naidoo, P.; Chalkidou, K.; Squires, N.; Ebrahim, S. Cuban medical training for South African students: A mixed methods study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colborn, R.P. Medical students’ financial dilemma. A study conducted at the University of Cape Town. S. Afr. Med. J. 1991, 79, 616–619. [Google Scholar]

- South African Government; Loram, C. Report of the Committee Appointed to Inquire into the Training of Natives in Medicine and Public Health Pretoria; Government Printers: Pretoria, South Africa, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Delobelle, P. The Health System in South Africa: Historical Perspectives and Current Challenges; Wolhuter, C.C., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 159–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rheinallt Jones, J.D.; Saffery, A.L. Findings of the Native Economic Commission, 1930–1932, Collated and Summarised. Bantu Stud. 1933, 7, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinallt Jones, J.D.; Saffery, A.L. Findings of the Native Economic Commission, 1930–1932, Collated and Summarised. Bantu Stud. 1934, 8, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapere, I. Report of a sub-committee appointed by the inter-university committee for African studies in January, 1932. Bantu Stud. 1934, 8, 219–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekings, J. Not a Single White Person Should Be Allowed to Go under: Swartgevaar and the Origins of South Africa’s Welfare State, 1924–1929. J. Afr. Hist. 2007, 48, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekings, J. The Carnegie Commission and the Backlash against Welfare State-Building in South Africa, 1931–1937. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2008, 34, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African National Bureau of Educational and Social Research. Awards Available for Undergraduate Study at South African Universities; Department of Education and Arts and Science: Pretoria, South Africa, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- University of Cape Town. Scholarship Opportunities for Study in the United States Announced; South African Committee on study and Training in the United States: Pretoria, South Africa, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Loram C, editor The training of Africans in Medicine and Public Health. Commission on World Mission and Evangelism of the World Council of Churches; International Review of Mission: Geneva, Switzerland, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- SouSouth African Government. Skills Development Act No. 97 of 1998; Contract No.: 97; Government Printers: Pretoria, South Africa, 1998. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a97-98.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health. Policy on Awarding of Bursaries for Full Time Study for Prospective Employees in the KwaZulu-Natal Province; Human Resources Development: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health. Amended Policy on Awarding of Bursaries for Full Time Study for Prospective Employees in the KwaZulu-Natal Province; Human Resources Development: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Limpopo Department of Health. Bursary Policy; Limpopo Department of Health: Polokwane, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Limpopo Department of Health. Human Resources Development and Training Policy: Bursary Policy; Limpopo Department of Health: Polokwane, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mpumalanga Provincial Government. Approved Provincial Bursary Policy; Mpumalanga Provincial Government: Nelspruit, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- North West Department of Health. Education, Training and Development Policy: Part E-Bursaries; North West Department of Health: Mahikeng, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Northern Cape Department of Health. Policy on Bursary; Northern Cape Department of Health: Kimberley, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Northern Cape Department of Health. Policy on Bursary Management; Northern Cape Department of Health: Kimberley, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Department of Health. Departmental Policy for Full-Time Higher Education Bursaries; Western Cape Department of Health: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- South African Government. Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and The Government of the Republic of Cuba on Co-Operation in the Fields of Public Health and Medical Sciences; South African Government: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- South African National Department of Health. Agreement between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Cuba on Co-Operation in the Field of Health; South African National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, G.H. Letter: Nationalisation of mission hospitals. S. Afr. Med. J. 1975, 49, 1684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sweet, H. ‘Wanted: 16 nurses of the better educated type’: Provision of nurses to South Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Nurs. Inq. 2004, 11, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingle, R. An Uneasy Story: The Nationalising of South African Mission Hospitals 1960–1976: A Personal Account, 1st ed.; SAMJ: Hillcrest, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, H.; Robertson, H.M. The University of Cape Town 1918–1948: The Formative Years; UCT: Cape Town, South Africa, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Coovadia, H.; Jewkes, R.; Barron, P.; Sanders, D.; McIntyre, D. The health and health system of South Africa: Historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet 2009, 374, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravenscroft, A.R. The geographical distribution of medical practitioners in the Union. S. Afr. Med. J. 1920, 18, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Inflation Tool. Inflation Timeline in South Africa (1965–2023). Available online: https://www.inflationtool.com/south-african-rand/1965-to-present-value (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- Republic of South Africa. Employment Equity Act No. 55 of 1998: Government Gazette Number 19370. 1998 Contract No.: 1323. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a55-98ocr.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- South African National Department of Health. National Recruitment Plan 2019; South African National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nyoni, J.; Christmals, C.D.; Asamani, J.A.; Illou, M.M.A.; Okoroafor, S.; Nabyonga-Orem, J.; Ahmat, A. The process of developing health workforce strategic plans in Africa: A document analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, J.; Gbary, A.; Awases, M.; Ndecki, P.; Chatora, R. Policies and Plans for Human Resources for Health: Guidelines for Countries in the WHO African Region; WHO Press: Brazaville, Congo, 2006; Available online: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/toolkit/15.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- United Nations Development Programme. Governance for Sustainable Human Development New York, USA: United Nations Development Programme. 1997. Available online: https://www.gdrc.org/u-gov/g-attributes.html (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Van Ryneveld, M.; Schneider, H.; Lehmann, U. Looking back to look forward: A review of human resources for health governance in South Africa from 1994 to 2018. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, E. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ditlopo, P.; Blaauw, D.; Bidwell, P.; Thomas, S. Analyzing the implementation of the rural allowance in hospitals in North West Province, South Africa. J. Public Health Policy 2011, 32 (Suppl. S1), S80–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, E. A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving, 5th ed.; Patashnik, E.M., Ed.; CQ Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Management Sciences for Health. Health Systems in Action: An eHandbook for Leaders and Managers; Management Sciences for Health: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Afriyie, D.O.; Nyoni, J.; Ahmat, A. The state of strategic plans for the health workforce in Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, S.; Woods, N.; Kalmus, O.; Birch, S.; Listl, S. Needs-based planning for the oral health workforce—Development and application of a simulation model. Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamani, J.A.; Akogun, O.B.; Nyoni, J.; Ahmat, A.; Nabyonga-Orem, J.; Tumusiime, P. Towards a regional strategy for resolving the human resources for health challenges in Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, W.J.; Fricker, R.S.; Ziegler, C.; Wiegman, D.L.; Rowland, M.L. Rural track training based at a small regional campus: Equivalency of training, residency choice, and practice location of graduates. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, A.P.; Liyanage, I.K.; De Silva, S.T.G.R.; Jayawardana, M.B.; Liyanage, C.K.; Karunathilake, I.M. Migration of Sri Lankan medical specialists. Hum. Resour. Health 2013, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, E.; Reid, S. Do South African medical students of rural origin return to rural practice? S. Afr. Med. J. 2003, 93, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dunbabin, J.S.; McEwin, K.; Cameron, I. Postgraduate medical placements in rural areas: Their impact on the rural medical workforce. Rural. Remote Health 2006, 6, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goma, F.M.; Tomblin Murphy, G.; MacKenzie, A.; Libetwa, M.; Nzala, S.H.; Mbwili-Muleya, C.; Rigby, J.; Gough, A. Evaluation of recruitment and retention strategies for health workers in rural Zambia. Hum. Resour Health 2014, 12 (Suppl. S1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, D. Developing Health Care Workforces for Uncertain Futures. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, D.F.; Brooks, P.M. On solutions to the shortage of doctors in Australia and New Zealand. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, M.; Heath, S.L.; Neufeld, S.M.; Samarasena, A. Evaluation of physician return-for-service agreements in Newfoundland and Labrador. Healthc. Policy 2013, 8, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Neufeld, S.M.; Mathews, M. Canadian return-for-service bursary programs for medical trainees. Healthc. Policy 2012, 7, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mapukata, N.O.; Couper, I.; Smith, J. The value of the WIRHE Scholarship Programme in training health professionals for rural areas: Views of participants. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2017, 9, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) Year | Justification for Inclusion |

|---|---|

| Bateman 2013a [27] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Bateman 2013b [28] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Colborn 1991 [35] | Reference to government funding in return for service, for financially distressed medical students at the University of Cape Town. |

| Delobelle 2013 [37] | History of the South African health system. |

| Donda et al. 2016 [29] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Loram 1929 [45] | Proposal for the need to increase intake and funding for Africans who desired to train in Medicine and Public Health. |

| Motala and Van Wyk 2019 [30] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Motala and Van Wyk 2021 [31] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Ncayiyana 2008 [32] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Quintana et al. 2012 [8] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Rheinallt Jones and Saffery 1933 [38] | Recommendations for the South African government to increase social assistance to Africans who want to study further, especially in the health sciences. |

| Rheinallt Jones and Saffery 1934 [39] | Recommendations for the South African government to increase social assistance to Africans who want to study further, especially in the health sciences. |

| Schapere 1934 [40] | Proposal for the need to increase the training of Africans in health sciences and how this would be funded. |

| Seekings 2007 [41] | Proposals for increased government social welfare in many sectors including education for both white and black South Africans. |

| Seekings 2008 [42] | Proposals for increased government social welfare in many sectors including education for both white and black South Africans. |

| South African Government 1998 [46] | Act on the need to improve knowledge and competencies of government employees, including career pathing and progression (in-service training). |

| South African government and Loram 1928 [36] | Proposal for the need to increase intake and funding for Africans who desired to train in Medicine and Public Health. |

| South African National Bureau of Educational and Social Research 1965 [43] | Early advertisement of different types of funding agreements for health science studies, some in return for service. |

| South African National Department of Health 1997 [14] | White paper proposing the structure of the proposed ‘new South African health system in 1997′ and how the health workforce capacity would be increased. |

| Squires et al. 2020 [33] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| Sui et al. 2019 [34] | History of South Africa and Cuba bilateral agreement on training medical students. |

| University of Cape Town 1950 [44] | First advertisement of return-of-service schemes recovered. |

| Policy documents (9) are embedded within the manuscript in Table S1. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mabunda, S.A.; Durbach, A.; Chitha, W.W.; Bodzo, P.; Angell, B.; Joshi, R. Development, Objectives and Operation of Return-of-Service Bursary Schemes as an Investment to Build Health Workforce Capacity in South Africa: A Multi-Methods Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212821

Mabunda SA, Durbach A, Chitha WW, Bodzo P, Angell B, Joshi R. Development, Objectives and Operation of Return-of-Service Bursary Schemes as an Investment to Build Health Workforce Capacity in South Africa: A Multi-Methods Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212821

Chicago/Turabian StyleMabunda, Sikhumbuzo A., Andrea Durbach, Wezile W. Chitha, Paidamoyo Bodzo, Blake Angell, and Rohina Joshi. 2023. "Development, Objectives and Operation of Return-of-Service Bursary Schemes as an Investment to Build Health Workforce Capacity in South Africa: A Multi-Methods Study" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212821

APA StyleMabunda, S. A., Durbach, A., Chitha, W. W., Bodzo, P., Angell, B., & Joshi, R. (2023). Development, Objectives and Operation of Return-of-Service Bursary Schemes as an Investment to Build Health Workforce Capacity in South Africa: A Multi-Methods Study. Healthcare, 11(21), 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212821