The Art of Childbirth of the Midwives of Al-Andalus: Social Assessment and Legal Implication of Health Assistance in the Cultural Diversity of the 10th–14th Centuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

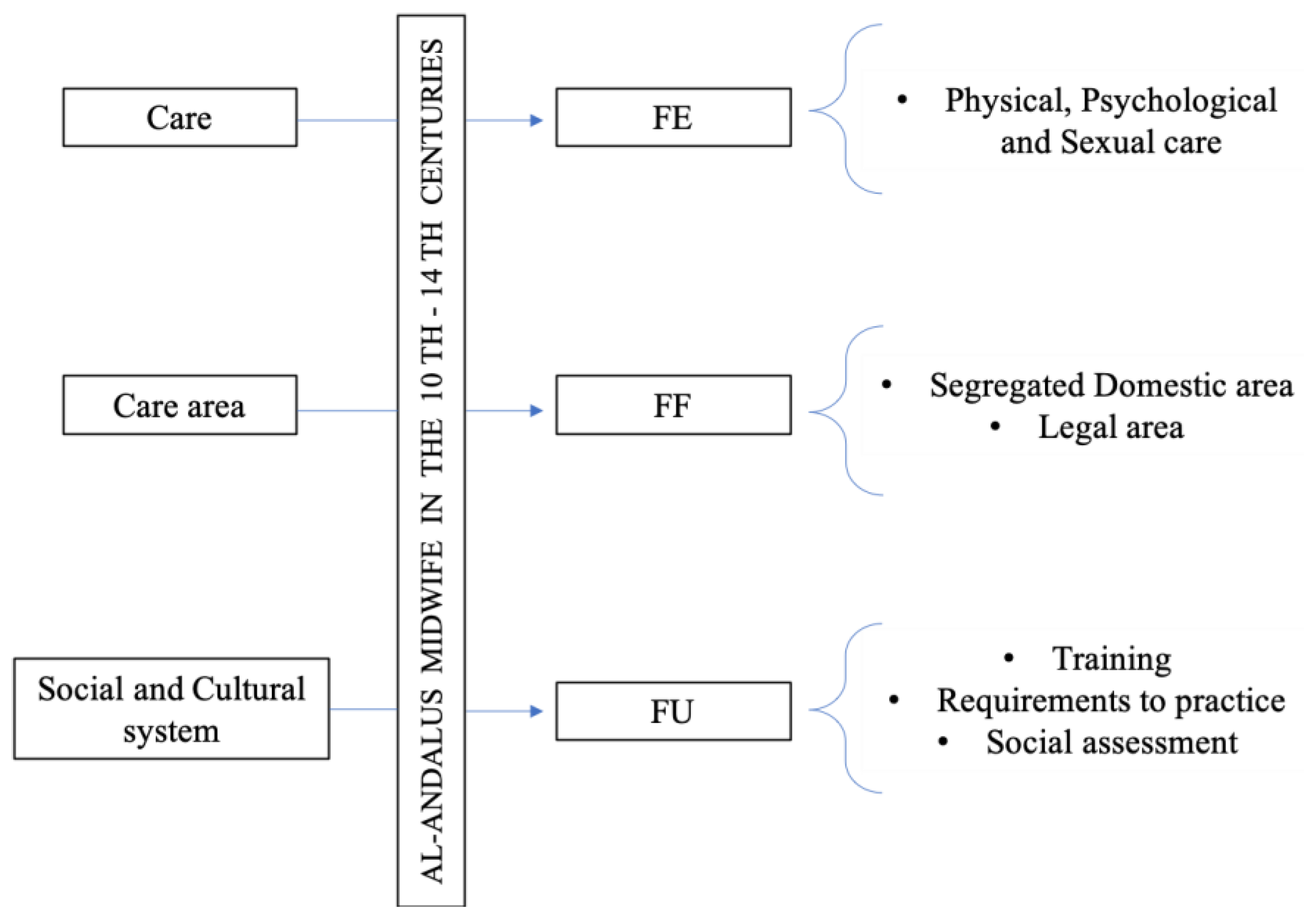

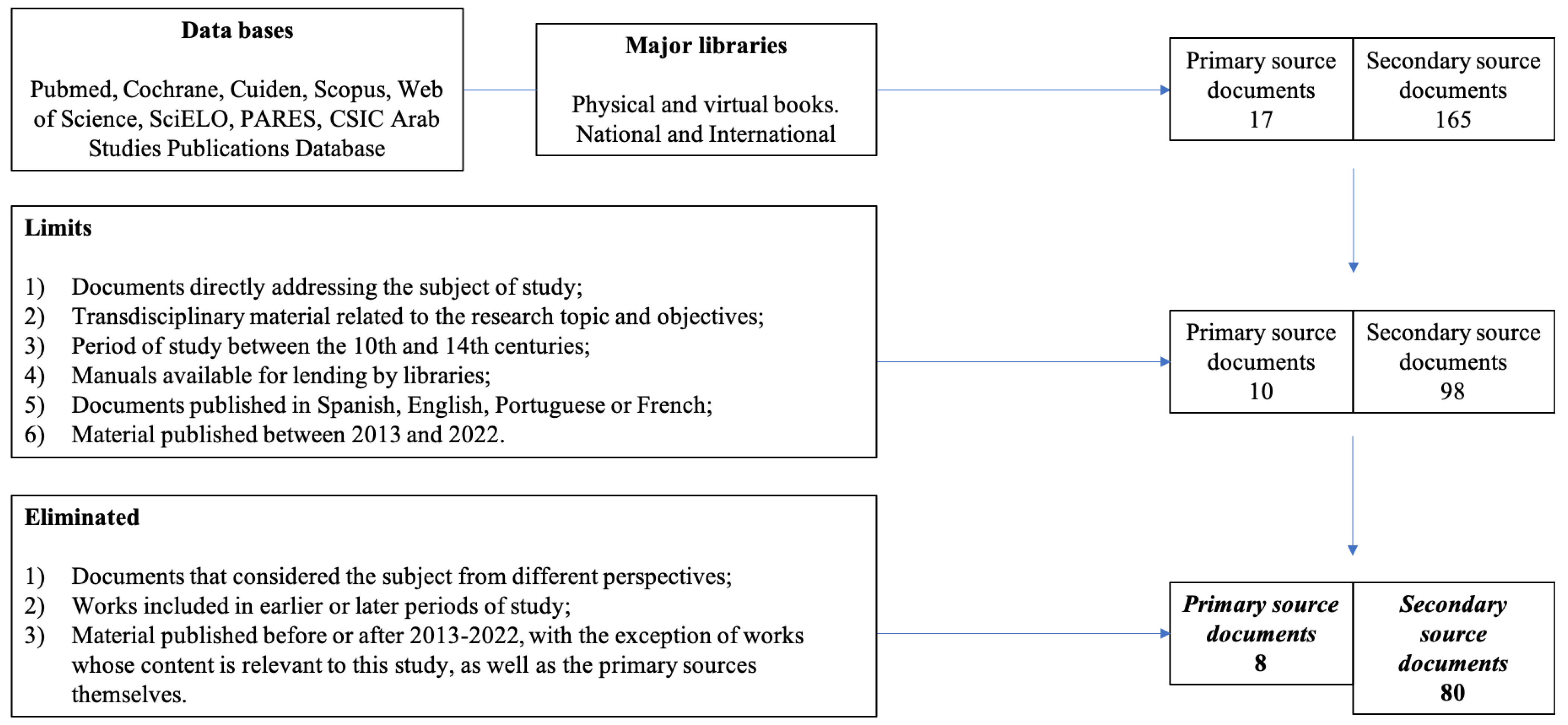

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Midwife Trade: Types and Requirements

3.2. The Social Position of the Midwife: Legal Aspects

3.2.1. The Social Assessment of the Andalusian Midwife

3.2.2. Known Women: Names of Those Dedicated to Care

3.2.3. Unknown Women: Made Invisible in Medical Treatises

3.2.4. The Midwife in the Courts: Legal Function and Other Aspects

3.2.5. Blood Kinship: An Unwritten Law

3.3. The Midwife’s Care Role

3.3.1. Care during Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Immediate Postpartum: Mother and Newborn

3.3.2. Postpartum Rituals, Fertility, Contraception, Abortion, and Other Areas of Qābila Intervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSMC | Dialectical structural model of care |

| FU | Functional unit |

| FF | Functional framework |

| EF | Functional element |

| PARES | Spanish Archives Portal |

References

- Mead, M. Masculino y Femenino; Minerva: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Siles, J. Historia de la Enfermería; Aguaclara: Alicante, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Siles, J. Los cuidados de enfermería en el marco de la historia social y la historia cultural. In La Transformación de la Enfermería Nuevas Miradas para la Historia; González, C., Martínez, F., Eds.; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2010; pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar]

- Siles González, J. Historia cultural de enfermería: Reflexión epistemológica y metodológica. Av. Enferm. 2010, 28, 120–128. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0121-45002010000300011&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Borges, A. Donde Viemos, Historia de Portugal; Caminho SA: Alfragide, Portugal, 2010; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Sidarus, A.Y. Fontes da História de al-Andalus e do Gharb; Centro de Estudos Africanose e Asiáticos: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Borges-Coelho, A. Portugal na Espanha Árabe; Caminho: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Espina-Jerez, B.; Domínguez-Isabel, P.; Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Pina-Queirós, P.J.; Bouzas-Mosquera, C. Una Excepción en la Trayectoria Formativa de las Mujeres: Al-Ándalus en los Siglos VIII-XII. Cult. Los. Cuid. 2019, 54, 194–205. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/96320 (accessed on 14 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fierro, M.I. La Mujer y el Trabajo en el Corán y el Hadiz. In La Mujer en al-Ándalus: Reflejos Históricos de su Actividad y Categorías Sociales; Colección del Seminario de Estudios de la Mujer; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 35–51. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10261/12321 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Shatzmiller, M. Women’s labour. In Labour in the Medieval Islamic World (Islamic History and Civilization (formerly Arab History and Civilization). Studies and Texts; Vol., 4), Brill, E.J., Eds.; Brill Academic Pub.: Leiden, The Netherlands; New York, NY, USA; Köln, Germany, 1994; pp. 347–368. [Google Scholar]

- Valdeón, J. La Reconquista: El Concepto de España: Unidad y Diversidad; Espasa Calpe: Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abellán, J. Poblamiento y sociedad en al-Ándalus. In IV-V Jornada de Cultura Islámica Almonaster la Real; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2006; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila, M.L. Las mujeres «sabias» en Al-Ándalus. In La Mujer en Al-Ándalus: Reflejos Históricos de su Actividad y Categorías Sociales; Viguera, M.J., Ed.; Andaluzas Unidas: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 139–184. [Google Scholar]

- Espina-Jerez, B.; Alaminos, M.A.; Gómez Cantarino, S.; Dominguez, P.; Moncunill, E. Los cuidados brindados por la mujer a la esclavitud andalusí: Siglos X-XV. In Conocimientos, Investigación y Prácticas en el Campo de la Salud: Innovación y Cambio en Competencias profesionales; ASUNIVEP: Almería, Spain, 2020; pp. 455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, P. Al-Ándalus. Estructura Antropológica de una Sociedad Islámica en Occidente; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ladero, M.F.; López, P. Introducción a la Historia del Occidente Medieval; Ramón Areces: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Provençal, E. Le siècle du califat de Cordoue. In Histoire de l’Espagne Musulmane; G.P. Maisonneuve: París, France; E. J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1950; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

- López, P. Algunas consideraciones sobre la legislación musulmana concernientes a los mozárabes. Espac. Tiempo Forma Ser. III Ha Mediev. 2007, 20, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, M. Historia de las Mujeres en Occidente. In Nombres sin voz: La Mujer y la Cultura en al-Ándalus; Duby, G., Perrot, M., Eds.; Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mesned Alesa, M.S. El Estatus de la Mujer en la Sociedad Árabo-Islámica Medieval Entre Oriente y Occidente; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2007; Available online: https://hera.ugr.es/tesisugr/16734154.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Soares, M.d.A. O Espaço Ibero-Magrebino Durante a Presença árabe em Portugal e Espanha (do Al-Garbe à Expansão em Marrocos); Palimage: Coimbra, Portugal, 2012; 336p. [Google Scholar]

- López, G. Las mujeres andalusíes en el discurso y en la práctica religiosos. In Al-Ándalus: Mujeres, Sociedad y Religión; Universidad de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 1992; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro, S. Matrimonios interreligiosos y pensiones (nafaqāt) en el derecho islámico. Su reflejo en el Kitāb al-Nafaqāt del andalusí Ibn Rašīq (s. XI). In VII Congreso Virtual Sobre Historia de Las Mujeres; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2015; pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Spectorsky, S.A. Women in Classical Islamic Law: A Survey of the Sources; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Do Souto, A.M.M. Médicos Medievais Naturais de Al-Ándaluz; By the Book: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, E.G. La Médecine Arabe; Librairie Coloniale et Orientaliste Larose: París, France, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥabīb, I. Mujtasar fi l-tibb (Compendio de Medicina); CSIC e Instituto de Cooperación con el Mundo Árabe (AECI): Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, K.M. Amulets. In Encyclopaedia of the Qur’ān; Pink, J., Ed.; University of Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2001; pp. 77–79. Available online: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-the-quran/amulets-EQSIM_00018?lang=de (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Samsó, J. Las Ciencias de los Antiguos en al-Ándalus; Colecciones Mapfre: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi Provençal, É. Histoire de l’espagne Musulmane; G.P. Maisonneuve: París, France; E. J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, L.F. Sobre el Ejercicio de la Medicina en al-Andalus: Una Fetua de Ibn Sahl. Anaquel Estudios Árabes. 1997, 2, 157–160. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/656914/_Sobre_el_ejercicio_de_la_medicina_en_al-Andalus_una_fetua_de_Ibn_Sahl_ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Cabanillas, M.I. La mujer en Al-Ándalus. In Proceedings of the IV Congreso Virtual Sobre Historia de las Mujeres, Virtual, 15–31 October 2012; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán, M.F.J.; Calero, M.Á.; Pérez, R.E.M.; Calama, A.M.S.; Higuera, A.T.; Concepción, M.B.A. La «qabila»: Historia de la Matrona Olvidada de al-Andalus. Matronas Profesión 2014, 15, 2–8. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4776748 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Castro, A.A. El Libro de la Generación del feto, el Tratamiento de las Mujeres Embarazadas y de los Recién Nacidos; Sociedad de pediatría de Andalucía Occidental y Extremadura: Sevilla, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles González, J.; Solano Ruiz, C. El Modelo Estructural Dialéctico de los Cuidados. Una guía facilitadora de la organización, análisis y explicación de los datos en investigación cualitativa. CIAIQ 2016. 2016, 2, 211–220. Available online: https://proceedings.ciaiq.org/index.php/ciaiq2016/article/view/754 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Espina-Jerez, B.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; de Dios-Aguado, M.; Cunha-Oliveira, A.; Siles-Gonzalez, J.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. Wet Nurse or Milk Bank? Evolution in the Model of Human Lactation: New Challenges for the Islamic Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9742. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35955096/ (accessed on 15 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Espina-Jerez, B.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; Cotto-Andino, M.; Aguado, M.d.D.; Siles-Gonzalez, J.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. Midwives in Health Sciences as a Sociocultural Phenomenon: Legislation, Training and Health (XV-XVIII Centuries). Med. Kaunas. Lith. 2022, 58, 1309. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36143986/ (accessed on 15 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Siles González, J.; Solano-Ruíz, C. Antropología Educativa de los Cuidados: Una Etnografía del Aula y las Prácticas Clínicas; Marfil: Alcoy, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. Available online: https://www.jclinepi.com/article/S0895-4356(14)00210-8/abstract (accessed on 23 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26134548/ (accessed on 23 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- al-Malik Ibn Habib, M. Kitab al-Wadiha (Tratado Jurídico); Arcas, M., Ed.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, G.; Jesús, M.; Martínez, A.C.G.G. Las Funciones de la Matrona en el Mundo Antiguo y Medieval. Una Mirada Desde la Historia. Matronas Profesión 2005, 6, 11–18. Available online: https://www.federacion-matronas.org/revista/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/vol6n1pag11-18.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Espina Jerez, B.; Gómez Cantarino, S.; Checa Peñalver, A.; Del Rocío Rodríguez López, C.; Navarro Rognoni, J.E. El Cuidado Femenino en las Figuras de Matrona y Enfermera: Denominación, Formación y Práctica Asistencial (s. XV-XVIII). In Conocimientos, Investigación y Prácticas en el Campo de la Salud: Enfoques Metodológicos Renovados; ASUNIVEP: Almería, Spain, 2022; pp. 221–228. Available online: https://ciise.es/9/contenido/textos/descargar_libro/249 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Flores, D.P. El Servicio de las Parteras Musulmanas en la Corte Castellana Bajo Medieval a Través de las Crónicas y Otros Testimonios Documentales. In Minorías en la España Medieval y Moderna (ss XV-XVII); Publications of eHumanista: Santa Bárbara, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 182–191. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5751161 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- El-Hamamsy, L. The Daya of Egypt: Survival in a Modernizing Society; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1973. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED117011 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Khaldûn, I. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. Bodies, Gender, Health, Disease: Recent Work on Medieval Women’s Medicine. Stud. Edieval. Renaiss. Hist. 2005, 2, 1–46. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/19979497/Monica_H_Green_Bodies_Gender_Health_Disease_Recent_Work_on_Medieval_Women_s_Medicine_2005_ (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Goldsmith, J. Childbirth Wisdom: From the World’s Oldest Societies, 2nd ed.; Closing the Circle Productions: Brooklin, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelder, G.J. Close Relationships: Incest and Inbreeding in Classical Arabic Literature; I.B. Tauris: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leiser, G. Medical Education in Islamic Lands from the Seventh to the Fourteenth Century. J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 1983, 38, 48–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temkin, O. Soranus Gynecology; Digital Library of India: Jaipur, India, 1956; Available online: http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.547535 (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Arabiat, D.H.; Whitehead, L.; Al Jabery, M.; Towell-Barnard, A.; Shields, L.; Abu Sabah, E. Traditional methods for managing illness in newborns and infants in an Arab society. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vasconcelos, J.L. Etnografía Portuguesa; INCM-Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007; Volume VIII. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, V. Mujeres y Repertorios Biográficos, Biografías y Género Biográfico en el Occidente Islámico; Estud Onomástico-Biográficos Al-Andal VIII.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 1997; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/29143751/Mujeres_y_repertorios_biogr%C3%A1ficos_biograf%C3%ADas_y_g%C3%A9nero_biogr%C3%A1fico_en_el_Occidente_Isl%C3%A1mico (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Pormann, P.E.; Savage-Smith, E. Medieval Islamic Medicine; The New Edinburgh Islamic Surveys: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, H. Manners and Customs of Fourteenth-Century Cairene Women: Female Anarchy versus Male Shar’i Order in Muslim Prescriptive Treatises. In Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; pp. 99–121. Available online: http://gender-middle-east.weebly.com/uploads/2/6/5/7/26578904/lutfi_manners_and_customs_ch.6_copy.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Abu al-Qasim, K.; al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi, A. Kitab at-Tasrif; Al-Matbaa Publishing: Lucknow, India, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, W.; Muntner, S. Maimonides’ Views on Gynecology and Obstetrics: English Translation of Chapter Sixteen of His Treatise, “Pirke Moshe” (Medical Aphorisms). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1965, 91, 443–448. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0002937865902620 (accessed on 26 February 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canaan, T. The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans. In Magic and Divination in Early Islam; Savage-Smith, E., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 125–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, L. Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1992; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bg61 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Arnaldez, R. Ibn Zuhr. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed.; Bearman, P., Bianquis, T., Bosworth, C.E., Van Donzel, E., Heinrich, W.P., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 976–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arenal, M. Los moros de Navarra en la Baja Edad Media. In Moros y Judíos en Navarra en la Baja Edad Media; Libros Hiperion: Madrid, Spain, 1984; pp. 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- Molénat, J.P. Privilégiées ou Poursuivies: Quatre Sages-Femmes Musulmanes dans la Castille du XV siècle. In Identidades Marginals; Estudios Onomástico- biográficos de al-Andalus; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2003; pp. 413–421. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=0oO68GslcYYC&pg=PA413&lpg=PA413&dq=Privilegi%C3%A9es+ou+poursuivies+quatre+sages-femmes+musulmanes&source=bl&ots=FNI859Imi2&sig=ACfU3U1XaCFHMpXzfI0hiedAXwKCbsr62g&hl=es&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjtxKHx6Or9AhXqxAIHHRKwC2oQ6AF6BAgiEAM#v=onepage&q=Privilegi%C3%A9es%20ou%20poursuivies%20quatre%20sages-femmes%20musulmanes&f=false (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- García Arancón, M.R. El Personal Femenino del Hostal de la Reina Blanca de Navarra (1425-1426). El Trabajo de las Mujeres en la Edad Media Hispana; Asociación Cultural Al-Mudayna: Madrid, Spain, 1988; pp. 27–45. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=591369 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Marín, M. Los saberes de las mujeres. In Vidas de Mujeres Andalusíes; Sarriá: Málaga, Spain, 2006; pp. 188–189. [Google Scholar]

- Edriss, H.; Rosales, B.N.; Nugent, C.; Conrad, C.; Nugent, K. Islamic Medicine in the Middle Ages. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 354, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, M. Two Women, One Man: Knowledge, Power, and Gender in Medieval Sunni Legal Thought. Int. J. Middle East. Stud. 1997, 29, 185–204. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/164016 (accessed on 29 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.E. In the House of the Law: Gender and Islamic Law in Ottoman Syria and Palestine; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000; 232p. [Google Scholar]

- de la Puente González, C. Free Fathers, Slave Mothers and Their Children: A Contribution to the Study of Family Structures in Al-Andalus. Imago Temporis Medium Aev. 2013, 7, 27–44. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4905242 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Giladi, A. Muslim Midwives: The Craft of Birthing in the Premodern Middle East; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/es/academic/subjects/history/middle-east-history/muslim-midwives-craft-birthing-premodern-middle-east?format=PB (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Shaham, R. The Expert Witness in Islamic Courts: Medicine and Crafts in the Service of Law; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Espina Jerez, B.; Gómez Cantarino, S.; Queirós, P.J.P.; Siles, J. La figura de la nodriza y su implicación en el parentesco de leche para la cultura islámica: Marco socio-cultural y jurídico. Cult. Los. Cuid. 2022, 26, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf-Obermeyer, C. Pluralism and Pragmatism: Knowledge and Practice of Birth in Morocco. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2000, 14, 180–201. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/649701 (accessed on 29 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Berkey, J.P. The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; Available online: https://moodle.swarthmore.edu/pluginfile.php/151607/mod_resource/content/1/Berkey_The%20Formation%20of%20Islam.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Abu-l-Walid, M.; Ahmad ibn Rushd, A. Kitab al-Kulliyyât al-Tibb (Colliget); Apud Intas, apud Haeredes Lucaeantonii Luntae: Rome, Italy, 1553. [Google Scholar]

- Wāfid, I. El Libro de la Almohada; Instituto Provincial de Investigaciones y Estudios Toledanos: Toledo, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- González, I. Posiciones Fetales, Aborto, Cesárea e Infanticidio. Un Acercamiento a la Ginecología y Puericultura Hispánica a través de tres Manuscritos Medievales. Miscelánea Mediev. Murc. 2009, 33, 99–122. Available online: http://revistas.um.es/mimemur/article/view/103391 (accessed on 15 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- González, I. La Cesárea. Rev. Digit. Iconogr. Mediev. 2013, 5, 1–15. Available online: https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/docs/621-2013-12-14-03.%20Ces%C3%A1rea.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- De Miguel Sesmero, J.R. La salud reproductiva en las Cántigas de Santa María de Alfonso X el Sabio: Una visión desde el ámbito médico. Santander Estud. Patrim. 2019, 2, 317–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, A. Children of Islam: Concepts of Childhood in Medieval Muslim Society; Macmillan: Houndmills, UK; London, UK; St. Antony’s College: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn, M.C. Quest for Conception: Gender, Infertility and Egyptian Medical Traditions; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelpia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Espina Jerez, B.; Siles-Gonzalez, J.; Solano-Ruiz, C.; Gómez-Cantarino, M. Women health providers: Materials on cures, remedies and sexuality in inquisitorial processes (15th–18th century). Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1178499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquart, D.; Thomasset, C.A. Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages; Princeton University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; 242p. [Google Scholar]

- Joaquim, T. Dar à luz: Ensaio Sobre as Práticas e Crenças da Gravidez, Parto e Pós-Parto em Portugal; Publicaciones Dom Quixote: Lisboa, Portugal, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Musallam, B.F. Sex and Society in Islam: Birth Control Before the Nineteenth Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983; 196p. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez-Tejero, M. Una Aproximación al Cuerpo Femenino a Través de la Medicina Medieval. Filanderas 2016, 1, 45–60. Available online: https://papiro.unizar.es/ojs/index.php/filanderas/article/view/1503 (accessed on 15 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ibn al-Jatib, M.b.A. Kitab al-Wusul li-hifz al-sihha fi-l-fusul, “Libro de Higiene”. In Traducido al Español Como Libro del Cuidado de la Salud Durante las Estaciones del Año; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pottier, R. Initiation a la Medecine Et a la Magie en Islam; Nouvelles Editions Latines: París, France, 1939; 128p. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. The Ottoman. Lady: A Social History from 1718 to 1918; Greenwood Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA; Westport, CT, USA; London, UK, 1986; 348p. [Google Scholar]

- Çaksen, H. Parents’ Supernatural Beliefs on Causes of Birth Defects: A Review from Islamic Perspective. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2023, 12, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidumo, E.M.; Ehlers, V.J.; Hattingh, S.P. Cultural knowledge of non-Muslim nurses working in Saudi Arabian obstetric units. Curationis 2010, 33, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jaroudi, D.H. Beliefs of subfertile Saudi women. Saudi Med. J. 2010, 31, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arabiat, D.H.; Whitehead, L.; Al Jabery, M.A.; Darawad, M.; Geraghty, S.; Halasa, S. Newborn Care Practices of Mothers in Arab Societies: Implication for Infant Welfare. J. Transcult. Nurs. Off. J. Transcult. Nurs. Soc. 2019, 30, 260–267. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30136917/ (accessed on 29 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Marín, M. Nombres sin voz: La Mujer y la Cultura en al-Andalus; Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cabré i Pairet, M.; Ortiz Gómez, T. Sanadoras, Matronas y Médicas en Europa: Siglos XII-XX; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters | Points Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed Cochrane Cuiden Scopus Web of Science SciELO PARES CSIC Arab Studies Publications Database | history of nursing AND midwives nursing AND midwife midwife AND requirements AND Muslim history women doctor AND Muslim history history of nursing AND gender AND legislation midwife AND traditional medicine midwife AND Quran Middle Ages and nursing | Last 10 years Article English/Spanish | Training Requirements to practice Social assessment Segregated domestic area Legal area Physical, psychological, and sexual care |

| Primary Source | Location | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ibn Ḥabīb. Mujtasar fi l-tibb (Compendium of Medicine). 9th century. | Library of the School of Translators in Toledo (Spain) | Al-Ándalus |

| Ibn Sa’īd ‘Arīb. El libro de la generación del feto, el tratamiento de las mujeres embarazadas y de los recién nacidos. 10th century. | Loaned by the National Library of Spain through the Library of the University of Castilla-La Mancha (Toledo, Spain) | |

| Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi [Abulcasis]. Kitab at-Tasrif. 10th century. | French National Library | |

| Ibn Habib A al M. Kitab al-Wadiha (legal treatise). 11th century. | Library of the School of Translators in Toledo (Spain) | |

| Ibn Wāfid. El libro de la Almohada. 11th century. | Library of the School of Translators in Toledo (Spain) | |

| Abu-l-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd (Averroes). Kitab al-Kulliyyât al-Tibb (Colliget). 12th century. | Digital Hispanic Library | |

| Ibn al-Jatib M b. A. Kitab al-Wusul li-hifz al-sihha fi-l-fusul, “Libro de Higiene”. 12th century. | Loaned by the Autonomous University of Madrid through the Library of the University of Castilla-La Mancha (Toledo, Spain) | |

| Ibn Khaldûn. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. 14th century. | JSTOR |

| Activity | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Assistance in conception | |

| Diagnosis of pregnancy | |

| Normal delivery | 9 lunar months When the head comes out before the body, it is easier and safer for the fetus |

| Premature delivery | 7 and 8 lunar months Before that, their survival is not assured |

| Complicated delivery | Pelvic or breech presentation, transverse position |

| Twin births, Siamese twin or multiple fetuses | |

| Deformities of newborns | Greater or lesser number of limbs and/or fingers on hands or feet |

| Placental extraction | |

| Hydatidiform mole or molar pregnancy | |

| Instrument | Use |

|---|---|

| Vaginal speculum | To open the vagina at its entrance to the uterus. Place the woman in a lithotomy position (“on a sofa with her legs falling and separated”) and insert the lubricated speculum blades. It was made of ebony or boxwood. |

| Impeller Midfa’ | There is no clear description of its use. It is interpreted that it could be used to grab the neck of the fetus and thus facilitate the exit of the rest of the body. |

| Cephalotribe Mishdakh This would be the precursor to the current forceps. | It has the shape of scissors whose blades are toothed jaws. It was used to grab the fetus’s head when it could not progress through the pelvic canal, either due to the size of its head (e.g., hydrocephalus is referred to) or the narrowness of the birth canal, and there was no other option for its delivery. It was not intended for the extraction of a live fetus. |

| Hook or separator Sinnara This would be similar to the current spatula. | It has the shape of a bar with a hook at its end. It was used when the fetus was stuck to the walls of the canal to assist in its extraction. Its use is described only in the case that the fetus was already dead. |

| Perforator or scalpel Mibda | It is a kind of scalpel without a handle. It is said that they were designed to be hidden between the midwife’s fingers and not to be seen. |

| Remedy | Use |

|---|---|

| Seeds of colocynth boiled in lily oil. Enema. | Prevent miscarriage in the 2nd–3rd month. |

| Fenugreek, fennel seeds and root, and celery. | Pain from miscarriage. Boil and drink several times a day. |

| Ginger, musk, celery seeds, asarum, cardamom, nutmeg, cinnamon. Put unperforated pearls of coral or amber. Electuary. | Flatulence during pregnancy. |

| Mucilage of fenugreek with sesame oil. | Induction of labor during prolonged labor and to increase the quality and quantity of breast milk after 2–3 days of birth. |

| Pyrethrum or soapwort. | Makes the woman sneeze and thereby contributes to the contractions, for the delivery of the fetus and placenta. |

| Mucilage of marshmallow, fenugreek, sesame oil, and dissolved gum. | Facilitate the delivery of the fetus in breech presentation, when one of the hands comes out first, or when the fetus has died in the womb. The four ingredients are mashed and mixed, applied to the vulva and lower abdomen. Then, the vaporizer is placed with only clean boiled water. Afterward, combine with pyrethrum. When the placenta does not come out with the previous remedy, apply manually on the placenta inside the uterus, let it act, and pull gently to avoid prolapse. |

| Pennyroyal, rue, aniseed, chamomile, artemisia, cassia, and centaury. Boil in water and apply with a vaporizer. Combine with pyrethrum. Cooked fenugreek over the genitals once the placenta has been expelled. | Stimulate detachment of the placenta in case of retention or for significant menstrual delays. |

| Chamomile, myrrh, valerian, carrot seed, anise, fennel seed and root, bitter, sweet, and cultivated rue and juniper. Drink. | Induce menstruation. |

| Yellow amber, almond gum, pomegranate flower, incense, rose leaves, and nut. Crush with powdered zargatona mucilage and sumac cooking water. Crushed jasmine flowers. Drink. | Stop menstruation when it exceeds the normal duration and any type of vaginal bleeding. |

| Vitriol (sulphate present in several metals) Quince syrup, toasted gum Arabic, and clay. Drink. | Stop bleeding. |

| Acacia “Olibanum” or oil of Lebanon Always mixed with egg white. | Stop bleeding and treat pain. |

| Sumac, pomegranate peel, and oak galls. Administer with a vaporizer. | Persistent vaginal bleeding. |

| Radish seed ointment with human or sheep milk. Mustard mashed with figs. Among others. | Freckles of the pregnant woman. They will be treated after delivery. |

| Intervention Cause | Mode |

|---|---|

| Hermaphroditism | Three possible forms are exposed. In all of them, “what grows must be cut and destroyed”. Then, the usual treatment for wound healing was used. |

| Excision of the clitoris and other growths in female genitals (female circumcision) | When the clitoris grows above its normal size, and can even become erect like male organs, it must be cut to the root of its growth to prevent serious bleeding. Then, heal and bandage like any other wound. |

| Imperforate vulva | The woman’s vulva is partially or completely closed. It can be congenital or acquired. If it is congenital, it would be an imperforate hymen. When the membrane is thin, the midwife performs a manual rupture. If it is thick, an incision with a scalpel must be made. Daily care and bandaging with dry linen. Sometimes it is due to large growths caused by cancerous tumors. These cases cannot be remedied by isolating the tumor. |

| Hemorrhoids, warts, and red pustules in the female vulva | The treatment and prognosis depend on their depth. The shallower they are, the better the prognosis and the easier to cure. The procedure consists of their removal, holding the warts with rough fabric and cutting them with a scalpel. Use medications to stop bleeding. |

| Uterine eruptions | Collections of pus occur, which must be opened with a scalpel and drained. When acute pain symptoms occur, pulse, inflammation, heat, and redness, use ointments that help to naturally suppurate it before breaking it. |

| Imperforate anus | Newborns are sometimes born with the anus closed by a thin membrane. The midwife will perforate it with a finger or scalpel, taking care not to reach the muscle. Soak a cotton ball and linen in oil, and treat it after each bowel movement and until it heals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Espina-Jerez, B.; Aguiar-Frías, A.M.; Siles-González, J.; Cunha-Oliveira, A.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. The Art of Childbirth of the Midwives of Al-Andalus: Social Assessment and Legal Implication of Health Assistance in the Cultural Diversity of the 10th–14th Centuries. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212835

Espina-Jerez B, Aguiar-Frías AM, Siles-González J, Cunha-Oliveira A, Gómez-Cantarino S. The Art of Childbirth of the Midwives of Al-Andalus: Social Assessment and Legal Implication of Health Assistance in the Cultural Diversity of the 10th–14th Centuries. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212835

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspina-Jerez, Blanca, Ana María Aguiar-Frías, José Siles-González, Aliete Cunha-Oliveira, and Sagrario Gómez-Cantarino. 2023. "The Art of Childbirth of the Midwives of Al-Andalus: Social Assessment and Legal Implication of Health Assistance in the Cultural Diversity of the 10th–14th Centuries" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212835