Adult Attachment and Fear of Missing Out: Does the Mindful Attitude Matter?

Abstract

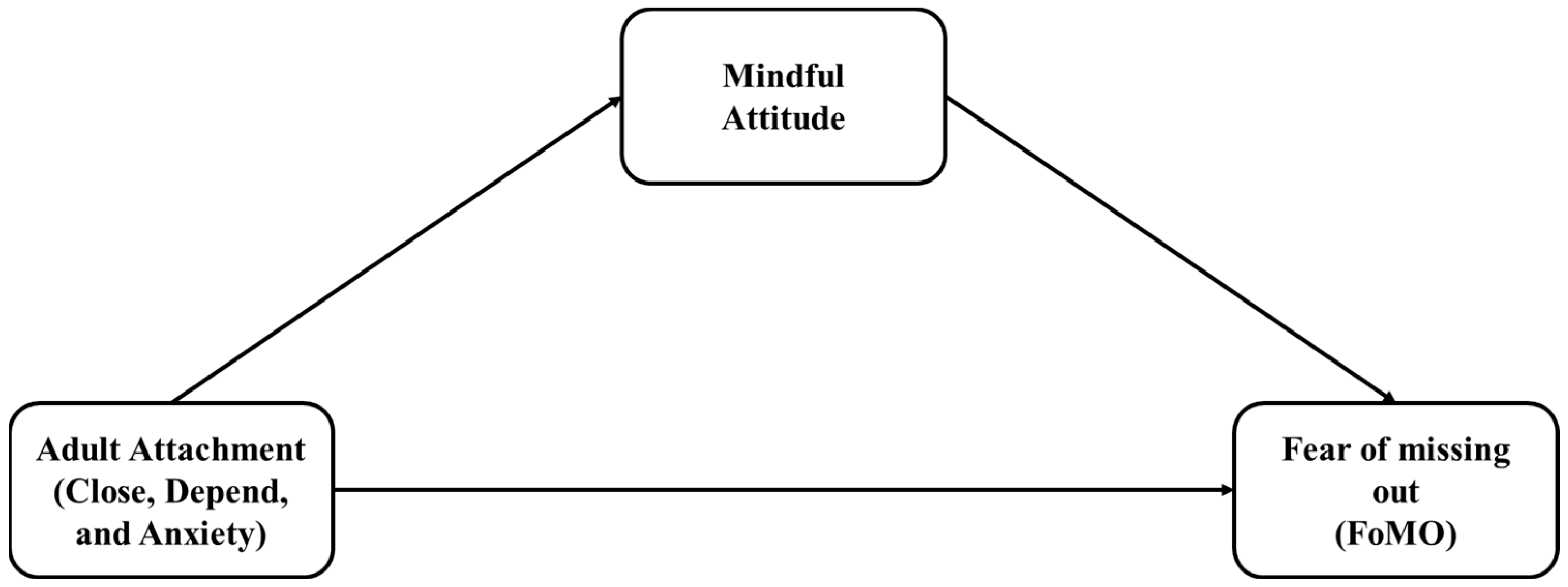

:1. Introduction

Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodkinson, C. ‘Fear of Missing Out’(FOMO) marketing appeals: A conceptual model. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberst, U.; Wegmann, E.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M.; Chamarro, A. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, J.L.; Swank, J.M. Mindful connections: A mindfulness-based intervention for adolescent social media users. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2019, 5, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.H.; Monin, B.; Dweck, C.S.; Lovett, B.J.; John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Misery has more company than people think: Underestimating the prevalence of others’ negative emotions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiórka, A. Facebook intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissism, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reagle, J. Following the Joneses: FOMO and conspicuous sociality. First Monday 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Z.G.; Krieger, H.; LeRoy, A.S. Fear of missing out: Relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2016, 2, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.L.; Swank, J.M. An examination of college students’ social media use, fear of missing out, and mindful attention. J. Coll. Couns. 2021, 24, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, H.; Bibby, P.A. Personality, fear of missing out and problematic Internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiru, J.; Oluwajana, D.; Biabor, O.S. Is the Global Pandemic Driving Me Crazy? The Relationship Between Personality Traits, Fear of Missing Out, and Social Media Fatigue During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 2309–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musetti, A.; Manari, T.; Billieux, J.; Starcevic, V.; Schimmenti, A. Problematic social networking sites use and attachment: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 31, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The bowlby-ainsworth attachment theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 1979, 2, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazan, C.; Shaver, P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troisi, G.; Parola, A.; Margherita, G. Italian validation of AAS-R: Assessing psychometric properties of Adult Attachment Scale—Revised in the Italian Context. Psychol. Stud. 2022, 67, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, N.L.; Read, S.J. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boustead, R.; Flack, M. Moderated-mediation analysis of problematic social networking use: The role of anxious attachment orientation, fear of missing out and satisfaction with life. Addict. Behav. 2021, 119, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Griffiths, M.D. The associations between attachment, self-esteem, fear of missing out, daily time expenditure, and problematic social media use: A path analysis model. Addict. Behav. 2023, 141, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holte, A.J.; Ferraro, F.R. Anxious, bored, and (maybe) missing out: Evaluation of anxiety attachment, boredom proneness, and fear of missing out (FoMO). Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 112, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J.G.; Ryan, R.M.; Couchman, C.E.; Deci, E.L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durao, M.; Etchezahar, E.; Albalá Genol, M.Á.; Muller, M. Fear of missing out, emotional intelligence and attachment in older adults in Argentina. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 51, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbro, F.; Muratori, F. La mindfulness: Un nuovo approccio psicoterapeutico in età evolutiva (Mindfulness: A new psychotherapeutic approach for children). Ital. J. Dev. Tal Neuropsychiatry 2012, 32, 248–259. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, N.G.; Manber, R.; Shapiro, S.L.; Constantino, M.J. Psychotherapist mindfulness and the psychotherapy process. Psychotherapy 2010, 47, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.J.; Balint, M.G.; Smolira, D.R.; Fredericksen, L.K.; Madsen, S. Predicting individual differences in mindfulness: The role of trait anxiety, attachment anxiety and attentional control. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P.R.; Lavy, S.; Saron, C.D.; Mikulincer, M. Social foundations of the capacity for mindfulness: An attachment perspective. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordon, S.L.; Finney, S.J. Measurement invariance of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale across adult attachment style. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2008, 40, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepping, C.A.; O’Donovan, A.; Davis, P.J. The differential relationship between mindfulness and attachment in experienced and inexperienced meditators. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayner, B. Emotion-focused mindfulness therapy. Pers.-Centered Exp. Psychother. 2019, 18, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, J.; Crane, C.; Germer, C.K.; Gold, E.; Heidenreich, T.; Mander, J.; Meibert, P.; Segal, Z. Principles for a Responsible Integration of Mindfulness in Individual Therapy. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, W.E.B.; Eisendrath, S.J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Theory and practice. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomas, T.; Medina, J.C.; Ivtzan, I.; Rupprecht, S.; Hart, R.; Eiroa-Orosa, F.J. The impact of mindfulness on well-being and performance in the workplace: An inclusive systematic review of the empirical literature. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 492–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; An, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, W. State mindfulness and positive emotions in daily life: An upward spiral process. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 141, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, L.; Rifayanti, R.; Amalia, P.R.; Gultom, L.M.K. Mindfulness Therapy to Lower the Tendency to Fear of Missing Out (FoMo). J. Aisyah J. Ilmu Kesehatan. 2023, 8, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.J. Mindfulness training and neural integration: Differentiation of distinct streams of awareness and the cultivation of well-being. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2007, 2, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xiong, W.; Liu, X.; An, J. Trait Mindfulness and Problematic Smartphone Use in Chinese Early Adolescent: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Negative Affectivity and Fear of Missing Out. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Italian version of the fear of missing out scale in emerging adults and adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2020, 102, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 810–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Boosting attachment security to promote mental health, prosocial values, and inter-group tolerance. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziani, C.A.; Voci, A. The Italian adaptation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised. TPM—Test. Psychometr. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 22, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.C.; Hayes, A.M.; Kumar, S.; Greeson, J.M.; Laurenceau, J. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007, 29, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola, M.; Palmiero, M.; D’Amico, S. Social sustainability in late adolescence: Trait Emotional Intelligence mediates the impact of the Dark Triad on Altruism and Equity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 840113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; D’Amico, S.; Palmiero, M. Working Memory and Divergent Thinking: The Moderating Role of Field-Dependent-Independent Cognitive Style in Adolescence. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertler, C.A.; Vannatta, R.A. Advanced and Multivariate Statistical Methods: Practical Application and Interpretation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola, M.; Palmiero, M.; D’Amico, S. Dark Triad and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The role of conspiracy beliefs and risk perception. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.; Anderson, V.N. Secure attachment and autonomy orientation may foster mindfulness. Contemp. Buddhism 2013, 14, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Brown, K.W.; Creswell, J.D. How integrative is attachment theory? Unpacking the meaning and significance of felt security. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.C.; Emerson, L.M.; Millings, A. The relationship between adult attachment orientation and mindfulness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1438–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment Security, Compassion, and Altruism. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 14, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brach, T. Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a Buddha; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, J.A.; Caputi, P.; Grenyer, B.F. Mindfulness and emotional regulation as sequential mediators in the relationship between attachment security and depression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Ryan, R. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.S.; Van Solt, M.; Cruz, R.E.; Philp, M.; Bahl, S.; Serin, N.; Canbulut, M. Social media and mindfulness: From the fear of missing out (FOMO) to the joy of missing out (JOMO). J. Consum. Aff. 2022, 56, 1312–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, N.; Kirkby, A.; Duncan, S.; Brown, R.J. Adult attachment style and childhood interpersonal trauma in non-epileptic attack disorder. Epilepsy Res. 2008, 79, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Verde, P.; Cacciapuoti, L.; Angelino, G.; Piccardi, L.; Bocchi, A.; Palmiero, M.; Nori, R. Do advanced spatial strategies depend on the number of flight hours? the case of military pilots. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Palmiero, M.; Piccardi, L.; D’Amico, S. The relationships between cognitive styles and creativity: The role of field dependence-independence on visual creative production. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Palmiero, M.; Bocchi, A.; Piccardi, L.; Nori, R.; D’Amico, S. Divergent thinking in Italian elementary school children: The key role of probabilistic reasoning style. Cogn. Process. 2022, 23, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perilli, E.; Scosta, E.; Perazzini, M.; Di Giacomo, D.; Ciuffini, R.; Bontempo, D.; Marcotullio, S.; Cobianchi, S. Cross-cultural correlates of homophobia: Comparison of Italian and Spanish attitudes towards homosexuals. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M.; Pino, M.C.; D’Amico, S. Exploring the psychosocial antecedents of sustainable behaviors through the lens of the positive youth development approach: A Pioneer study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perilli, E.; Perazzini, M.; Di Giacomo, D.; Marrelli, A.; Ciuffini, R. Attitudine “mindful”, emozioni e perdono di sé in adolescenza: Una ricerca correlazionale. Riv. Psichiatr. 2020, 55, 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Lawlor, M.S. The effects of a mindfulness-based education program on pre-and early adolescents’ well-being and social and emotional competence. Mindfulness 2010, 1, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perilli, E.; Perazzini, M.; Bontempo, D.; Ranieri, F.; Di Giacomo, D.; Crosti, C.; Marcotullio, S.; Cobianchi, S. Reduced Anxiety Associated to Adaptive and Mindful Coping Strategies in General Practitioners Compared with Hospital Nurses in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic Primary Care Reorganization. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 891470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolea, S. The Courage To Be Anxious. Paul Tillich’s Existential Interpretation of Anxiety. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2020, 6, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlikova, M.; Maturkanič, P.; Akimjak, A.; Mazur, S.; Timor, T. Social Interventions in the Family in the Post-COVID Pandemic Period. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2023, 14, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturkanič, P.; Tomanová Čergeťová, I.; Konečná, I.; Thurzo, V.; Akimjak, A.; Hlad, Ľ.; Zimny, J.; Roubalová, M.; Kurilenko, V.; Toman, M.; et al. Well-Being in the Context of COVID-19 and Quality of Life in Czechia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, X.; Wen, Z.; Zhou, J. Fear of missing out and problematic social media use as mediators between emotional support from social media and phubbing behavior. Addict. Behav. 2020, 107, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 23.24 | 4.33 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Education (years) | 14.11 | 1.90 | 0.52 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Adult Attachment—Close | 3.36 | 0.84 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 1 | ||||

| 4. Adult Attachment—Depend | 2.67 | 0.77 | 0.11 | 0.17 ** | 0.45 ** | 1 | |||

| 5. Adult Attachment—Anxiety | 3.03 | 1.12 | −0.19 * | −0.16 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.58 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. Mindful Attitude | 10.26 | 2.00 | 0.17 * | 0.19 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.44 ** | 1 | |

| 7. FoMO | 2.67 | 0.71 | −0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.18 * | −0.04 | 0.32 ** | −0.30 ** | 1 |

| α | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| Independent Variable | Mediator | Dependent Variable | Path a 1 | Path b 2 | Direct Effect 3 | Indirect Effect 4 | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Attachment—Close | Mindful Attitude | FoMO | 0.51 [0.154, 0.862] | −0.07 [−0.119, −0.011] | −0.05 [−0.188, −0.079] | −0.03 [−0.073, −0.002] | −0.09 [−0.220, 0.044] |

| Adult Attachment—Depend | Mindful Attitude | FoMO | 0.46 [0.186, 0.731] | −0.08 [−0.147, −0.008] | 0.05 [−0.082, 0.185] | −0.04 [−0.077, −0.003] | 0.02 [−0.116, 0.147] |

| Adult Attachment—Anxiety | Mindful Attitude | FoMO | −0.55 [−0.845, −0.262] | −0.07 [−0.119, −0.011] | 0.21 [0.099, 0.322] | 0.03 [0.005, 0.071] | 0.25 [0.138, 0.356] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perazzini, M.; Bontempo, D.; Giancola, M.; D’Amico, S.; Perilli, E. Adult Attachment and Fear of Missing Out: Does the Mindful Attitude Matter? Healthcare 2023, 11, 3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233093

Perazzini M, Bontempo D, Giancola M, D’Amico S, Perilli E. Adult Attachment and Fear of Missing Out: Does the Mindful Attitude Matter? Healthcare. 2023; 11(23):3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233093

Chicago/Turabian StylePerazzini, Matteo, Danilo Bontempo, Marco Giancola, Simonetta D’Amico, and Enrico Perilli. 2023. "Adult Attachment and Fear of Missing Out: Does the Mindful Attitude Matter?" Healthcare 11, no. 23: 3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233093

APA StylePerazzini, M., Bontempo, D., Giancola, M., D’Amico, S., & Perilli, E. (2023). Adult Attachment and Fear of Missing Out: Does the Mindful Attitude Matter? Healthcare, 11(23), 3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233093