Alleged Malpractice in Orthopedic Surgery in The Netherlands: Lessons Learned from Medical Disciplinary Jurisprudence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database and Data Collection

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

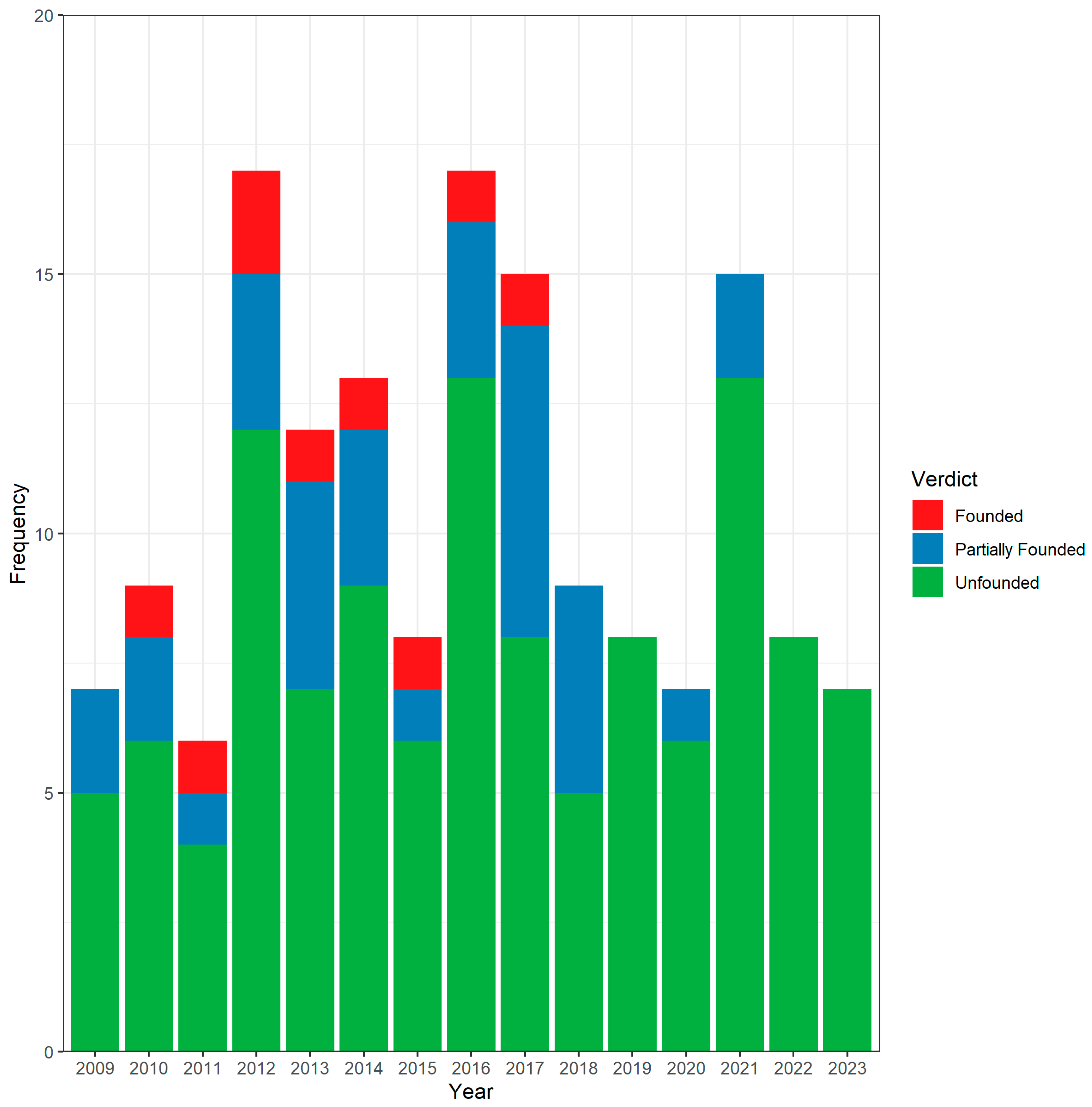

3.1. Case Characteristics

3.2. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jena, A.B.; Seabury, S.; Lakdawalla, D.; Chandra, A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, C.J.; Roumeliotis, A.G.; Karras, C.L.; Murthy, N.K.; Karras, M.F.; Tran, H.M.; Yerneni, K.; Potts, M.B. Overview of medical malpractice in neurosurgery. Neurosurg. Focus 2020, 49, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleiter, K.E. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009, 11, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studdert, D.M.; Mello, M.M.; Sage, W.M.; DesRoches, C.M.; Peugh, J.; Zapert, K.; Brennan, T.A. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005, 293, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.A.; Sampson, N.R.; Flynn, J.M. The prevalence of defensive orthopaedic imaging: A prospective practice audit in Pennsylvania. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2012, 94, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, M.K.; Obremskey, W.T.; Natividad, H.; Mir, H.R.; Jahangir, A.A. Incidence and costs of defensive medicine among orthopedic surgeons in the United States: A national survey study. Am. J. Orthop. 2012, 41, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rynecki, N.D.; Coban, D.; Gantz, O.; Gupta, R.; Ayyaswami, V.; Prabhu, A.V.; Ruskin, J.; Lin, S.S.; Beebe, K.S. Medical Malpractice in Orthopedic Surgery: A Westlaw-Based Demographic Analysis. Orthopedics 2018, 41, e615–e620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agout, C.; Rosset, P.; Druon, J.; Brilhault, J.; Favard, L. Epidemiology of malpractice claims in the orthopedic and trauma surgery department of a French teaching hospital: A 10-year retrospective study. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2018, 104, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, M.B.; Blandino, A.; Del Sordo, S.; Vignali, G.; Novello, S.; Travaini, G.; Berlusconi, M.; Genovese, U. Alleged malpractice in orthopaedics. Analysis of a series of medmal insurance claims. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2018, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougereau, G.; Marty-Diloy, T.; Langlais, T.; Pujol, N.; Boisrenoult, P. Litigation after primary total hip and knee arthroplasties in France: Review of legal actions over the past 30 years. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2022, 142, 3505–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardinangeli, C.; Giannace, C.; Cerciello, S.; Grassi, V.M.; Lodise, M.; Vetrugno, G.; De-Giorgio, F. A Fifteen-Year Survey for Orthopedic Malpractice Claims in the Criminal Court of Rome. Healthcare 2023, 11, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhafaji, F.Y.; Frederiks, B.J.; Legemaate, J. The Dutch system of handling complaints in health care. Med. Law 2009, 28, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- KNMG. Dossier. Available online: https://www.knmg.nl/advies-richtlijnen/dossiers/tuchtrecht (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Tuchtcolleges Voor de Gezondheidszorg. Welke Maatregelen Kan Een Tuchtcollege Opleggen. Available online: https://www.tuchtcollege-gezondheidszorg.nl/documenten/vragen-enantwoorden/welke-maatregelen-kan-een-tuchtcollege-opleggen (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Kwee, R.M.; Kwee, T.C. Medical disciplinary jurisprudence in alleged malpractice in radiology: 10-year Dutch experience. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 3507–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchtcolleges Voor de Gezondheidszorg. Ik Heb Een Klacht. Available online: https://www.tuchtcollegegezondheidszorg.nl/ik-heb-een-klacht (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Prismant. Aantal Werkzame Specialisten Per Specialisme En Uitstroom Van Specialisten in De Komende 20 Jaar. Available online: https://capaciteitsorgaan.nl/app/uploads/2019/03/190301_Prismant_Werkzame-specialisten-2019.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Tuchtcolleges Voor de Gezondheidszorg. Wat Kost Het Indienen Van Een Klacht. Available online: https://www.tuchtcollege-gezondheidszorg.nl/documenten/vragen-enantwoorden/wat-kost-het-indienen-van-een-klacht (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Sauder, N.; Emara, A.K.; Rullán, P.J.; Molloy, R.M.; Krebs, V.E.; Piuzzi, N.S. Hip and Knee Are the Most Litigated Orthopaedic Cases: A Nationwide 5-Year Analysis of Medical Malpractice Claims. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, S443–S449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goud, A.L.; Harlianto, N.I.; Ezzafzafi, S.; Veltman, E.S.; Bekkers, J.E.J.; van der Wal, B.C.H. Reinfection rates after one- and two-stage revision surgery for hip and knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2023, 143, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, H. Litigations in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: Analysis and outcomes of medicolegal claims during the last 10 years in the United Kingdom National Health Service. EFORT Open Rev. 2021, 6, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, E.M.; Bordewijk, E.M.; Klemann, D.; Driessen, S.R.C.; Twijnstra, A.R.H.; Jansen, F.W. Medical malpractice claims in laparoscopic gynecologic surgery: A Dutch overview of 20 years. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 5418–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wansink, L.; Kuypers, M.I.; Boeije, T.; van den Brand, C.L.; de Waal, M.; Holkenborg, J.; Ter Avest, E. Trend analysis of emergency department malpractice claims in the Netherlands: A retrospective cohort analysis. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Santaroni, F.; Lanzetti, R.; Failla, G.; Gentili, A.; Ricciardi, W. Developing a Data-Driven Approach in Order to Improve the Safety and Quality of Patient Care. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 667819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcărea, V.; Gheorghe, I.R.; Petrescu, C. The Assessment of Perceived Service Quality of Public Health Care Services in Romania Using the SERVQUAL Scale. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 6, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, L.M.; Weenink, J.W.; Winters, S.; Robben, P.B.; Westert, G.P.; Kool, R.B. The disciplined healthcare professional: A qualitative interview study on the impact of the disciplinary process and imposed measures in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laarman, B.S.; Bouwman, R.J.; de Veer, A.J.; Hendriks, M.; Friele, R.D. How do doctors in the Netherlands perceive the impact of disciplinary procedures and disclosure of disciplinary measures on their professional practice, health and career opportunities? A questionnaire among medical doctors who received a disciplinary measure. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, F.R.K.; Wimmer-Boelhouwers, P.; Dijt, O.X.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; Schepers, T. Claims in orthopedic foot/ankle surgery, how can they help to improve quality of care? A retrospective claim analysis. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2021, 31, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengerink, I.; Reijman, M.; Mathijssen, N.M.; Eikens-Jansen, M.P.; Bos, P.K. Hip Arthroplasty Malpractice Claims in the Netherlands: Closed Claim Study 2000–2012. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 1890–1893.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| I. Warning. This is a reproof for misconduct, but not culpable negligence. |

| II. Reprimand. This is a reproof for culpable negligence. |

| III. A monetary fine up to EUR 4.500. |

| IV. A (conditional) suspension for up to one year. This measure may also be imposed together with a fine. |

| V. Partial prohibition to practice. |

| VI. Complete prohibition to practice. |

| Total Group (n = 158) | Unfounded Verdict (n = 114) | (Partially) Founded Verdict (n = 44) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training level | ||||

| Specialist | 151 (96%) | 108 (95%) | 43 (98%) | 0.78 |

| Resident | 7 (4%) | 6 (5%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Subspecialty | ||||

| Knee | 34 (22%) | 30 (16%) | 4 (9%) | 0.06 |

| Hip | 31 (20%) | 19 (17%) | 12 (27%) | |

| Ankle | 25 (16%) | 20 (18%) | 5 (11%) | |

| Spine | 22 (14%) | 10 (9%) | 12 (27%) | |

| Shoulder | 18 (11%) | 12 (11%) | 6 (14%) | |

| Hand | 7 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Oncology | 3 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Elbow | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Pediatric | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 14 (9%) | 9 (8%) | 5 (11%) | |

| Category | 0.86 | |||

| Incorrect treatment/wrong diagnosis | 107 (68%) | 79 (69%) | 28 (64%) | |

| Providing no or insufficient care | 17 (11%) | 13 (11%) | 4 (9%) | |

| Providing insufficient information | 10 (6%) | 7 (6%) | 3 (7%) | |

| Inaccurate statement or documentation | 8 (5%) | 5 (4%) | 3 (7%) | |

| No or delayed referral | 4 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Improper treatment | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Breach of confidentiality | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Other | 7 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 4 (9%) | |

| Percentage of physicians with an attorney | 94% | 94% | 95% | 0.99 |

| Percentage of patients with an attorney | 47.5% | 33.3% | 80% | <0.001 |

| Time between filing and verdict in months | 9.9 (IQR: 7.6–12.5) | 9.8 (IQR: 7.6–12.2) | 9.9 (IQR: 7.5–12.8) | 0.60 |

| Number of appeals | 68 (43%) | 48 (42%) | 20 (45%) | |

| Rejected | 61 (90%) | 48 (100%) | 13 (65%) | |

| Granted | 7 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (35%) | |

| Appellant | ||||

| Specialist | 12 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (52%) | |

| Patient | 59 (83%) | 48 (100%) | 11 (48%) |

| Main Components of Founded Verdicts |

|---|

| Wrong diagnosis |

| Not performing additional imaging |

| Inadequate documentation in the electronic health record |

| Not adhering to orthopedic guidelines |

| Incorrect or insufficient acquisition of informed consent |

| Not discussing the risks of the operation |

| Incorrect operation indication |

| Incorrect time-out procedure, operating on the wrong side |

| Intraoperative errors |

| Incorrect surgical technique |

| Inadequate documentation of operation report |

| Inadequate postoperative care |

| Failure to refer to another specialist |

| Accessing the electronic health record and spreading information without consent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harlianto, N.I.; Harlianto, Z.N. Alleged Malpractice in Orthopedic Surgery in The Netherlands: Lessons Learned from Medical Disciplinary Jurisprudence. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243111

Harlianto NI, Harlianto ZN. Alleged Malpractice in Orthopedic Surgery in The Netherlands: Lessons Learned from Medical Disciplinary Jurisprudence. Healthcare. 2023; 11(24):3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243111

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarlianto, Netanja I., and Zaneta N. Harlianto. 2023. "Alleged Malpractice in Orthopedic Surgery in The Netherlands: Lessons Learned from Medical Disciplinary Jurisprudence" Healthcare 11, no. 24: 3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243111

APA StyleHarlianto, N. I., & Harlianto, Z. N. (2023). Alleged Malpractice in Orthopedic Surgery in The Netherlands: Lessons Learned from Medical Disciplinary Jurisprudence. Healthcare, 11(24), 3111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243111