The Relationship between Subjective Aging and Cognition in Elderly People: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

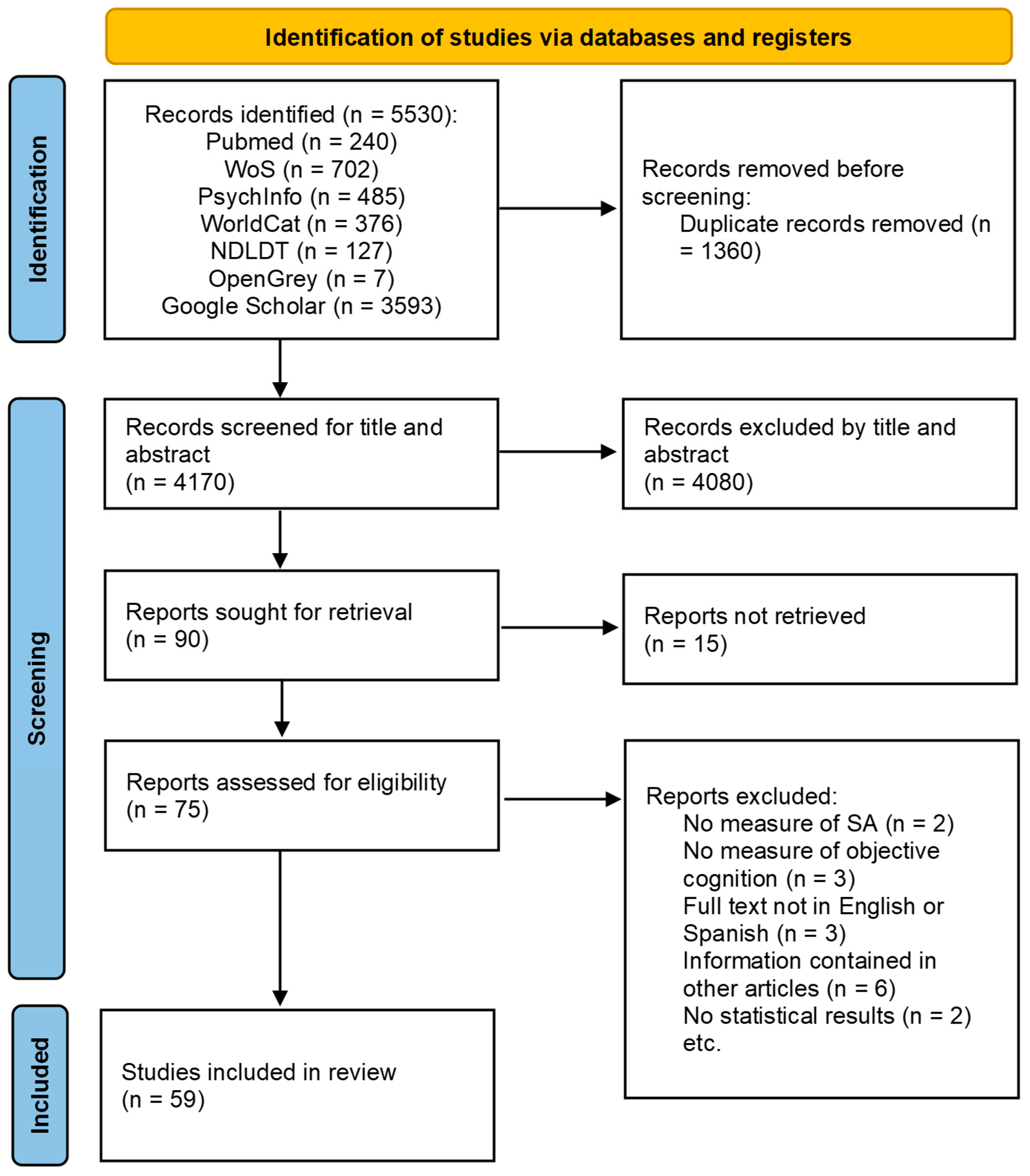

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Participant Characteristics and Sampling

3.3. Effect of Subjective Aging on Cognition

3.4. Cognitive Domains and Measures

3.5. Subjective Aging Constructs and Measures

3.6. Moderator Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, K.H.; Xu, H.; Wu, B. Gender differences in quality of life among community-dwelling elderly adults in low- and middle-income countries: Results from the Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velaithan, V.; Tan, M.-M.; Yu, T.-F.; Liem, A.; Teh, P.-L.; Su, T.T. The association of self-perception of ageing and quality of life in elderly adults: A systematic review. Gerontologist 2023, gnad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bülow, M.H.; Söderqvist, T. Successful ageing: A historical overview and critical analysis of a successful concept. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 31, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, J.; Martin, S.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Chatterji, S.; Garin, N.; Koskinen, S.; Leonardi, M.; Miret, M.; Moneta, V.; Olaya, B.; et al. Factors associated with active aging in Finland, Poland, and Spain. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, M.; O’Hanlon, A.; McGee, H.M.; Hickey, A.; Conroy, R.M. Cross-sectional validation of the Aging Perceptions Questionnaire: A multidimensional instrument for assessing self-perceptions of aging. BMC Geriatr. 2007, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, H.; Leventhal, E.A.; Contrada, R.J. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: A perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. Stereotype Embodiment: A Psychosocial Approach to Aging. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovel, H.; Carmel, S.; Raveis, V.H. Relationships Among Self-perception of Aging, Physical Functioning, and Self-efficacy in Late Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2019, 74, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, S.; Warner, L.M.; Ziegelmann, J.P.; Wolff, J.K.; Schüz, B. How do negative self-perceptions of aging become a self-fulfilling prophecy? Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villiers-Tuthill, A.; Copley, A.; McGee, H.; Morgan, K. The relationship of tobacco and alcohol use with ageing self-perceptions in elderly people in Ireland. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Gu, J.; Xue, F.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X. The association between self-perceptions of aging and antihypertensive medication adherence in elderly Chinese adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, A.-K.; Wolff, J.K.; Warner, L.M.; Schüz, B.; Wurm, S. The role of physical activity in the relationship between self-perceptions of ageing and self-rated health in elderly adults. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.R.; Zonderman, A.B.; Slade, M.D.; Ferrucci, L. Age Stereotypes Held Earlier in Life Predict Cardiovascular Events in Later Life. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent-Cox, K.A.; Anstey, K.J.; Luszcz, M.A. Longitudinal Change of Self-Perceptions of Aging and Mortality. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Kasl, S.V. Longitudinal Benefit of Positive Self-Perceptions of Aging on Functional Health. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, E.; Igelström, H.; Vikman, I.; Larsson, A.; Pauelsen, M. Positive Self-Perceptions of Aging Play a Significant Role in Predicting Physical Performance among Community-Dwelling Elderly Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurm, S.; Benyamini, Y. Optimism buffers the detrimental effect of negative self-perceptions of ageing on physical and mental health. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brothers, A.; Kornadt, A.E.; Nehrkorn-Bailey, A.; Wahl, H.-W.; Diehl, M. The Effects of Age Stereotypes on Physical and Mental Health Are Mediated by Self-perceptions of Aging. J. Gerontol. 2021, 76, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Miche, M.; Brothers, A.F.; Barrett, A.E.; Diehl, M.; Montepare, J.M.; Wahl, H.-W.; Wurm, S. The influence of subjective aging on health and longevity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Debreczeni, F.; Bailey, P.E. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Subjective Age and the Association with Cognition, Subjective Well-Being, and Depression. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, C.; Kramer, A.F.; Wilson, R.S.; Lindenberger, U. Enrichment Effects on Adult Cognitive Development: Can the Functional Capacity of Elderly Adults Be Preserved and Enhanced? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2008, 9, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, A.L.; Wolff, J.K. Bidirectional Associations Between Self-Perceptions of Aging and Processing Speed Across 3 Years. GeroPsych 2017, 30, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Shin, H.R.; Park, S.; Cho, S.E. The moderating effect of subjective age on the association between depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning in Korean elderly adults. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Ferrucci, L.; Zonderman, A.B.; Slade, M.D.; Troncoso, J.; Resnick, S.M. A culture–brain link: Negative age stereotypes predict Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Psychol. Aging 2016, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.; Kim, H.; Chey, J.; Youm, Y. Feeling How Old I Am: Subjective Age Is Associated with Estimated Brain Age. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.C.; Berntsen, D. People over forty feel 20% younger than their age: Subjective age across the lifespan. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006, 13, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, B. Age identity: A cross-cultural global approach. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steverink, N.; Westerhof, G.J.; Bode, C.; Dittmann-Kohli, F. The Personal Experience of Aging, Individual Resources, and Subjective Well-Being. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2001, 56, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.K.; Wahl, H.W. Awareness of Age-Related Change: Examination of a (Mostly) Unexplored Concept. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2010, 65B, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Wurm, S. Longitudinal Research on Subjective Aging, Health, and Longevity: Current Evidence and New Directions for Research. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 35, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Brothers, A.; Wahl, H.-W. Self-Perceptions and Awareness of Aging: Past, Present, and Future; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Leifheit-Limson, E. The Stereotype-Matching Effect: Greater Influence on Functioning When Age Stereotypes Correspond to Outcomes. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spuling, S.M.; Klusmann, V.; Bowen, C.E.; Kornadt, A.E.; Kessler, E.-M. The uniqueness of subjective ageing: Convergent and discriminant validity. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, S.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Brothers, A.; Diehl, M.; Wahl, H.-W.; Ballard, C.; Collins, R.; Corbett, A.; Brooker, H.; Clare, L. Differences in awareness of positive and negative age-related changes accounting for variability in health outcomes. Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, S.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ballard, C.; Collins, R.; Anstey, K.J.; Diehl, M.; Brothers, A.; Wahl, H.-W.; Corbett, A.; Hampshire, A.; et al. Cross-sectional association between objective cognitive performance and perceived age-related gains and losses in cognition. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, A.E. Questionnaire measures of self-directed ageing stereotype in elderly adults: A systematic review of measurement properties. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L. Are elderly adults perceived as a threat to society? Exploring perceived age-based threats in 29 nations. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P. The Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale: A Revision. J. Gerontol. 1975, 30, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Wahl, H.-W.; Barrett, A.E.; Brothers, A.F.; Miche, M.; Montepare, J.M.; Westerhof, G.J.; Wurm, S. Awareness of aging: Theoretical considerations on an emerging concept. Dev. Rev. 2014, 34, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A. Trajectories of normal cognitive aging. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisky, E.L. Changes in Cognitive Function in Human Aging. In Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms; Riddle, D.R., Ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murman, D.L. The Impact of Age on Cognition. Semin. Hear. 2015, 36, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, V.; Sproesser, G.; Wolff, J.K.; Renner, B. Positive Self-perceptions of Aging Promote Healthy Eating Behavior Across the Life Span via Social-Cognitive Processes. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2019, 74, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, S.A.; Siedlecki, K.L. Leisure Activity Engagement and Positive Affect Partially Mediate the Relationship Between Positive Views on Aging and Physical Health. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 72, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Segel-Karpas, D.; Cohn-Schwartz, E.; Ayalon, L. Self-perceptions of aging and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of loneliness. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boss, L.; Kang, D.-H.; Branson, S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the elderly adult: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, E.; Caballero, F.F.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Olaya, B.; Haro, J.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Miret, M. Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrira, A.; Hoffman, Y.; Bodner, E.; Palgi, Y. COVID-19-Related Loneliness and Psychiatric Symptoms Among Elderly Adults: The Buffering Role of Subjective Age. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, M.; Karim, H.T.; Becker, J.T.; Lopez, O.L.; Anderson, S.J.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Zmuda, M.D.; Butters, M.A. Late-life depression and increased risk of dementia: A longitudinal cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Connors, M.H. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2020, 12, e12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippon, I.; Steptoe, A. Is the relationship between subjective age, depressive symptoms and activities of daily living bidirectional? Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 214, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Marengoni, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Roso-Llorach, A.; Rizzuto, D.; Zucchelli, A.; Qiu, C.; Fratiglioni, L.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A. Multimorbidity burden and dementia risk in elderly adults: The role of inflammation and genetics. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.R.; Bavishi, A. Survival Advantage Mechanism: Inflammation as a Mediator of Positive Self-Perceptions of Aging on Longevity. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 73, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voelkner, A.R.; Caskie, G.I.L. Awareness of age-related change and its relationship with cognitive functioning and ageism. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2023, 30, 802–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Luchetti, M.; Aschwanden, D.; Terracciano, A. The mediating role of biomarkers in the association between subjective aging and episodic memory. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2023, 78, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langballe, E.M.; Skirbekk, V.; Strand, B.H. Subjective age and the association with intrinsic capacity, functional ability, and health among elderly adults in Norway. Eur. J. Ageing 2023, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D. Role of Positive Age Beliefs in Recovery from Mild Cognitive Impairment Among Elderly Persons. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e237707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.; Weiss, D.; Broulíková, H.M.; Sunderaraman, P.; Barker, M.S.; Joyce, J.L.; Azar, M.; McKeague, I.; Kriesl, W.C.; Cosentino, S. Examining the role of aging perceptions in Subjective Cognitive Decline. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2022, 36, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, C.; Dumitrache, C.G.; Rubio, L.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Self-perceptions of ageing and perceived health status: The mediating role of cognitive functioning and physical activity. Ageing Soc. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, S.; Martyr, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ballard, C.; Collins, R.; Pentecost, C.; Rusted, J.M.; Quinn, C.; Anstey, K.J.; Kim, S.; et al. Attitudes Toward Own aging and Cognition among Individuals living with and without dementia: Findings from the IDEAL programme and the PROTECT study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrigle, C.A.; Ward, M.; Kenny, R.A. Negative aging perceptions and cognitive and functional decline: Are you as old as you feel? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, S.; Siebert, J.S.; Diehl, M.; Brothers, A.; Wahl, H.-W. Identifying predictors of self-perceptions of aging based on a range of cognitive, physical, and mental health indicators: Twenty-year longitudinal findings from the ILSE study. Psychol. Aging 2022, 37, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, A.; Lam, J.; Thomas, M.L.; Daly, R.; Lee, E.E.; Jeste, D.V. Subjective Age and its Relationships with Physical, Mental, and Cognitive Functioning: A Cross-sectional Study of 1004 Community-Dwelling Adults across the Lifespan. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 152, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaspar, R.; Wahl, H.-W.; Diehl, M.; Zank, S. Subjective views of aging in very old age: Predictors of 2-year change in gains and losses. Psychol. Aging 2022, 37, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; Luo, Y.; Sun, J.; Chang, H.; Hu, H.; Zhao, B. Depression and Cognition Mediate the Effect of Self-Perceptions of Aging Over Frailty Among Elderly Adults Living in the Community in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 830667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Drewelies, J.; Duezel, S.; Lachman, M.E.; Smith, J.; Eibich, P.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Demuth, I.; Lindenberger, U.; Wagner, G.G.; et al. Subjective age and attitudes toward own aging across two decades of historical time. Psychol. Aging 2022, 37, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Neupert, S.D. Dynamic awareness of age-related losses predict concurrent and subsequent changes in daily inductive reasoning performance. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 39, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoblow, H.F. The Influence of Self-Perceptions of aging on Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Adult Dyads. Master’s Thesis, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Luchetti, M.; Aschwanden, D.; Terracciano, A. Subjective age and multiple cognitive domains in two longitudinal samples. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 150, 110616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E.P.; Zaheed, A.B.; Sharifian, N.; Sol, K.; Kraal, A.Z.; Zahodne, L.B. Subjective Age, Depressive Symptoms, and Cognitive Functioning across Five Domains. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2021, 43, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönstein, A.; Dallmeier, D.; Denkinger, M.; Rothenbacher, D.; Klenk, J.; Bahrmann, A.; Wahl, H.-W. Health and Subjective Views on Aging: Longitudinal Findings from the ActiFE Ulm Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, J.; Marques, S.; Ramos, M.R.; de Vries, H. Cognitive functioning mediates the relationship between self-perceptions of aging and computer use behavior in late adulthood: Evidence from two longitudinal studies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Du, X.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Feng, W.; Wu, Y. Does elderly subjective age predict poorer cognitive function and higher risk of dementia in middle-aged and elderly adults? Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Canada, B.; Terracciano, A. The Association Between Subjective Age and Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome: Results From a Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 2023–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisvetrová, H.; Herzig, R.; Bretšnajdrová, M.; Tomanová, J.; Langová, K.; Školoudík, D. Predictors of quality of life and attitude to ageing in elderly adults with and without dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Ferrucci, L. When Culture Influences Genes: Positive Age Beliefs Amplify the Cognitive-Aging Benefit of APOE ε2. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, e198–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Shi, J.; Yao, J.; Fu, H. Relationship Between Activities of Daily Living and Attitude Toward Own Aging Among the Elderly in China: A Chain Mediating Model. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 91, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A. Reductions in cognitive functioning are associated with decreases in satisfaction with aging. Longitudinal findings based on a nationally representative sample. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 89, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.S.; Braun, T.; Wahl, H.-W. Change in attitudes toward aging: Cognitive complaints matter more than objective performance. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, L.; Li, X.; Li, J. Subjective age and memory performance among elderly Chinese adults: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 91, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerino, E.; O’Brien, E.; Almeida, D. Feeling Elderly and Constrained: Synergistic Influences of Control Beliefs and Subjective Age on Cognition. Innov. Aging 2020, 4 (Suppl. 1), 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.S.; Wahl, H.-W.; Schröder, J. The Role of Attitude Toward Own Aging for Fluid and Crystallized Functioning: 12-Year Evidence from the ILSE Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Lachman, M.E. Getting elderly faster? changes in subjective age are tied to functional health and memory. Innov. Aging 2017, 1 (Suppl. 1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggle, C. Subjective Age, Lifestyle Behaviours and Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Adults: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Master’s Thesis, Maynooth University, Kildare, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Ferrucci, L. Positive age beliefs protect against dementia even among elders with high-risk gene. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebert, J.S.; Wahl, H.-W.; Degen, C.; Schröder, J. Attitude toward own aging as a risk factor for cognitive disorder in old age: 12-year evidence from the ILSE study. Psychol. Aging 2018, 33, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Luchetti, M.; Terracciano, A. Subjective age and risk of incident dementia: Evidence from the National Health and Aging Trends survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 100, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrrell, C. Stereotypes, Attitudes about Aging, and Optimism and their Impacts on Vocabulary Performance; University of Colorado: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Luchetti, M.; Terracciano, A. Feeling elderly and the development of cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 966–973. [Google Scholar]

- Jaconelli, A.; Terracciano, A.; Sutin, A.R.; Sarrazin, P.; Raffard, S.; Stephan, Y. Subjective age and dementia. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 40, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D.A.; Kenny, R.A. Negative perceptions of aging modify the association between frailty and cognitive function in elderly adults. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 100, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.A.; King-Kallimanis, B.L.; Kenny, R.A. Negative perceptions of aging predict longitudinal decline in cognitive function. Psychol. Aging 2016, 31, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. Self-Perceptions of Aging in Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults: A Longitudinal Study. En ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis, Fordham University, New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Y.; Sutin, A.R.; Caudroit, J.; Terracciano, A. Subjective age and changes in memory in elderly adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagood, E.W.; Gruenewald, T.L. Negative self-perceptions of aging predict declines in memory performance over time. Gerontologist 2015, 55 (Suppl. 2), 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülür, G.; Hertzog, C.; Pearman, A.M.; Gerstorf, D. Correlates and moderators of change in subjective memory and memory performance: Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontology 2015, 61, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihira, H.; Furuna, T.; Mizumoto, A.; Makino, K.; Saitoh, S.; Ohnishi, H.; Shimada, H.; Makizako, H. Subjective physical and cognitive age among community-dwelling elderly people aged 75 years and elderly: Differences with chronological age and its associated factors. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasteen, A.L.; Pichora-Fuller, M.K.; Dupuis, K.; Smith, S.; Singh, G. Do negative views of aging influence memory and auditory performance through self-perceived abilities? Psychol. Aging 2015, 30, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenkin, S.D.; Laidlaw, K.; Allerhand, M.; Mead, G.E.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J. Life course influences of physical and cognitive function and personality on attitudes to aging in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1417–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, Y.; Caudroit, J.; Jaconelli, A.; Terracciano, A. Subjective Age and Cognitive Functioning: A 10-Year Prospective Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 22, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.L. The Influence of Self-Perceptions of Aging on Elderly Adults’ Cognition and Behavior. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Zonderman, A.B.; Slade, M.D.; Ferrucci, L. Memory Shaped by Age Stereotypes over Time. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 67, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindi, S. Determinants of Stress Reactivity and Memory Performance in Elderly Adults; McGill University Libraries: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, R.; Watts, S.; Jones, R.; Tod, A.; Elliman, R. Self-reported quality of life ratings of people with dementia: The role of attitudes to aging. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paggi, M.; Jopp, D.; Schmitt, M. The Cognitive Effects of Aging Self-Stereotypes in Elderly and Middle-Aged Adults; Fordham University: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.S.; Hong, C.H. P3-035: Relationship between ‘discrepancy of subjective age and chronological age’ and cognition in the non cognitive LV impaired elderly. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2010, 6, S459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.L. Perception Is Reality: The Power of Subjective Age and Its Effect on Physical, Psychological, and Cognitive Health; Brandeis University: Waltham, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.; Langer, E. Aging free from negative stereotypes: Successful memory in China among the American deaf. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia; WHO Guidelines: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gluhm, S.; Goldstein, J.; Loc, K.; Colt, A.; Van Liew, C.; Corey-Bloom, J. Cognitive Performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Across the Healthy Adult Lifespan. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. Off. J. Soc. Behav. Cogn. Neurol. 2013, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation | Design | Sampling | Sample | SA | Cognition | Moderator | Covariate | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voelkner & Caskie, 2023 [55] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · 215 participants. · 66 years or elderly. · No dementia or cognitive impairment. · Living in the US. · Mean age of 69.06 (sd = 3.49) · 66% female | Awareness of age-related change (AARC-50) | Memory (word recall) Reasoning (word series, number series and letter series) | Ageism | Yes | There was a direct effect of cognitive losses (b = −0.17, p < 0.001) and total losses (b = −0.69, p < 0.001) on memory, as well as of cognitive gains (b = −0.12, p < 0.001), cognitive losses (b = −0.09, p < 0.001), total gains (b = −0.56, p < 0.001) and total losses (b = −0.39, p < 0.001) on reasoning. Ageism did not mediate this relationship. |

| Stephan et al., 2023 [56] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 2423 participants. · 50 years or elderly at baseline. · 60% female. · Mean age of 66.89 (sd = 9.22) | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) | Memory (word recall) | Biomarkers | Yes | There was a direct effect of subjective age (b = −1.13, p < 0.001) and self-perceptions of aging (b = −0.27, p < 0.001), and biomarkers mediated it. |

| Langballe et al., 2023 [57] | Cross-sectional | NORSE | · 817 participants. · 60 years or elderly. · 48.87% female. · 353 participants 60–69 years, 329 70–79 years, and 135 80 or elderly. | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Global cognition (MoCA) | No | Yes | There was no significant relationship between subjective age and cognitive capacity. |

| Levy & Slade, 2023 [58] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 1716 participants. · 65 years or elderly. · Without dementia at baseline measurement. · 55.5% female. · Mean age of 77.8 years (sd = 7.5). | Age beliefs (PGCMS) | Cognitive decline (TICS) | No | Yes | Participants with MCI had 30.2% greater likelihood of recovering normal cognitive status if they held positive age beliefs and recovered 2 years faster. |

| Chapman et al., 2022 [59] | Cross-sectional | Parent study on subjective cognitive decline | · 136 participants. · Normal cognition and psychological status · 67.6% females. · Mean age of 73.69 (sd = 6.79). | Age stereotypes (ad hoc and IAT) Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) Age identification (ad hoc) | Memory (word recall) | No | Yes. | Age stereotype and age identification did not correlate with objective cognition nor explained a significant amount of variance over cognition in the regression analysis. |

| Fernández-Jiménez et al., 2022 [60] | Cross-sectional | ELES_PS | · 1124 participants. · Community-dwelling. ·50 years or elderly. · Living in Spain. · 54.4% female. ·Mean age of 64.84 (sd = 10.12). | Attitudes to aging (ad hoc) Self-perceptions of aging (ad hoc) | Global cognition (MMSE) | No | Yes | Self-perceptions of aging correlated with cognitive functioning (r = 0.173, p < 0.01), and its path was significant (Bca = 0.848). Cognitive functioning mediates the relationship between self-perceptions of aging and perceived health (B = 0.0032, SE = 0.002, p < 0.01). |

| Sabatini et al., 2022 [61] | Cross-sectional | PROTECT; 2019 sample. | · 6192 participants. · 50 years or elderly. · No dementia point. · 76% female. · Mean age of 66.1 years (sd = 7). | Awareness of age-related change (AARC-10) | Global cognition (digit span, self-ordered search, paired learning, and grammatical reasoning) | No | Yes | Class 1 (many gains, few losses) showed better cognition compared with class 2 (moderate gains, few losses), 3 (many gains, moderate losses) and 4 (many gains, many losses) in all four cognitive measures. |

| McGarrigle et al., 2022 [62] | Longitudinal | TILDA | · 4031 participants. · 50 years or elderly. · Subset analysis of elderly adults (65 years or elderly; n = 2359) | Self-perceptions of aging (APQ) | Global cognition (MMSE) | Depression, self-rated health, loneliness, smoking, physical function, alcohol consumption. | Yes | Participants within the highest tertile of negative APQ had a higher probability of being classified in the cognitive decline trajectory (RRR = 1.82 after controlling for covariates. This link was partially mediated (40%), notably by loneliness (22%) and poor self-rated health (7%). The result was similar in the 65 years or elderly subsample if loneliness became the strongest mediator. |

| Sabatini et al., 2022 [63] | Longitudinal | ILSE | · 103 participants. · Without dementia. · 50.5% females. · Mean age at 20-year follow-up of 82.5 years (sd = 1). | Self-perceptions of aging (AARC-50) Attitudes towards own aging (PGCMS) | Fluid intelligence (digit span, SDMT and block design) Crystallized intelligence (information, similarities, and picture completion) | No | Yes | A decline in digit symbol test score predicted fewer AARC gains (small effect size, R2 = 0.07) and higher AARC losses (small effect size, R2 = 0.03). However, change in cognition did not predict attitudes towards own aging. |

| Aftab et al., 2022 [64] | Cross-sectional | SAGE | · 1004 participants. · Community-dwelling · No dementia or terminal illness Age group 1 (21–39 years; n = 161), group 2 (40–59 years; n = 224), group 3 (60–79 years; n = 314) and group 4 (80+ years; n = 305). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Global cognition (TICS) | No | Yes | There was no correlation between age discrepancy and cognition in any age group. |

| Kaspar et al., 2022 [65] | Longitudinal | Non-random | · 912 participants. · With follow-up. · 80 years or elderly. · 50.24% female. · Mean age at baseline of 87 years (sd = 4.5) | Awareness of age-related change (AARC-10) | Global cognition (DemTect) | No | Yes | Intra-individual changes in cognition were not significantly associated with changes in AARC gains or losses. |

| Yuan et al., 2022 [66] | Longitudinal | Non-random | · 822 participants. · 65 years or elderly. · Cognitively healthy; 57.06% female. · Mean age of 70 (sd = 7). | Self-perceptions of aging (B-APQ) | Global cognition (MMSE) | No | Yes | There was a significant correlation between cognition and SPA (r = −0.175, p < 0.001). |

| Wahl et al., 2022 [67] | Longitudinal | BASE | BASE (1990/93 and 2017/18 cohort); 512 participants. Mean age of 77. | Views on aging (composite score of age discrepancy) Attitudes towards own aging (PGCMS). | Speed of processing (SDMT) | No | Yes | Positive attitudes towards aging correlated with speed of processing (r = 0.23, p < 0.05). |

| Zhu & Neupert, 2021 [68] | Cross-sectional | Mindfulness and Anticipatory Coping Everyday (MACE) study | · 112 participants. · 60–90 years old. · Living in the US. · Without cognitive impairment. · Mean age of 64.65 (sd = 4.86). · 56.3% female. | Awareness of age-related change (AARC-20) | Reasoning (letter series and item-number comparison) Memory (word recall) | No | Yes | There was an association between daily AARC losses and letter series scores (concurrent B = −0.09, lagged B = −0.09), but not with AARC gains. AARC gains or losses were not related to either word recall or number comparison. |

| Sabatini et al., 2021 [36] | Cross-sectional | PROTECT | · 6056 participants. · Cognitively healthy. · 76.2% female. · Mean age of 66 years (sd = 7). · 3111 participants were middle-aged (51–65 years); 2473 were in early old age (66–75 years) and 472 were in advanced old age (≥76 years). | Awareness of age-related change (cognitive AARC-50 subscale and AARC-10) Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | · Working memory (self-ordered search and digit span) · Reasoning (grammatical reasoning) · Memory (paired learning) | No | Yes | AARC gains and losses in cognition and AARC total losses predicted working memory and reasoning. AARC total gains predicted working memory and reasoning but not memory. Subjective age predicted working memory. AARC gains in cognition were predictors of cognition in the middle-aged and early old subsamples but not in the advanced old subsample. AARC losses in cognition predicted cognition in all subsamples. |

| Skoblow, 2021 [69] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 933 dyads. · 50 years or elderly. · 50% female. · Mean age for women of 63.91 (sd = 7.64). Mean age for men of 66.77 (sd = 7.79) | Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) | Memory (word recall) | No | Yes | There was no significant association between own or partner’s SPA and memory change at baseline or follow-up. |

| Stephan, et al., 2021 [70] | Longitudinal | HRS and MIDUS | · 2549 participants from HRS. No MCI at baseline; 60% female. Mean age of 69.66 (sd = 7.36). · 2499 participants from MIDUS. No MCI at baseline; 54% female. Mean age of 46.24 (sd = 11.25). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall, logic memory and brave man history) Visuospatial (constructional praxis and MMSE) Verbal fluency (category fluency) Speed–attention–executive (letter cancellation, SDMT, TMT a and B, stop and go) Reasoning (number series) | No | Yes | Elderly subjective age related to lower scores in episodic memory (MIDUS d = 0.14; HRS d = 0.24) and speed–attention–executive (MIDUS d = 0.25; HRS d = 0.33) in both samples. Elderly SA related to lower fluency (d = 0.3) and visuospatial ability (d = 0.25) in HRS sample, and the relationship between subjective age and episodic memory was stronger for elderly participants (B = −0.04) and participants with lower depression symptoms (B = 0.04) in HRS sample. After excluding participants with MCI, the relationships remained significant. |

| Morris et al., 2021 [71] | Cross-sectional | HRS | · 993 participants. · 65 years or elderly. · Without dementia. · 58.81% female. · Mean age of 75.85 (sd = 7.49) | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall, logic memory and brave man history) Executive function (number series, TMT-B and visual reasoning) Visuospatial (constructional praxis) Speed of processing (letter cancellation and backwards count) Language (category fluency and naming) | Depression and chronological age | Yes | There was a direct effect of SA on episodic memory (b = 0.072, p < 0.01), executive functioning (b = 0.062, p < 0.01), language (b = 0.07, p < 0.25) and processing speed (b = −0.85, p < 0.001) but not visuoconstruction (b = 0.45, p > 0.05). Depression mediated 26.39% of the association between SA and episodic memory, 32.26% for executive functioning, 21.42% for language, and 23.35% for processing speed. However, after accounting for depression and covariates, only the effects of subjective age on language (b = 0.015, p = 0.27) and speed of processing (b = −0.2, p = 0.005) remained. |

| Schönstein et al., 2021 [72] | Longitudinal | ActiFE Ulm | · 526 participants. · With follow-up. · Age between 65 and 90 years at baseline. · 57% male. | Views of aging (PGCMS) Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Global cognition (MMSE) | No | Yes | General cognition did not significantly improve the prediction model for attitudes towards own aging (b = −0.04, p > 0.05) nor for subjective age (b = −0.03, p > 0.05). |

| Mariano et al., 2021 [73] | Longitudinal | HRS and DEAS | · Study 1: 3404 participants; 50 years or elderly. · Study 2: 4871 participants; 40 years or elderly. | Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) | Memory (word recall) Speed of processing (SDMT) | No | Yes | Study 1: Self-perceptions of aging correlated with cognition at T1 (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), T2 (r = 0.18, p < 0.001), T3 (r = 0.18, p < 0.001) and in the cross-lagged model (b = 0.09, p < 0.001). Study 2: Self-perceptions of aging correlated with cognition at T1 (r = 0.18, p < 0.001) and T2 (r = 0.22, p < 0.001) and in the cross-lagged model (Δχ2 (1) = 25.52, p < 0.001). |

| Qiao et al., 2021 [74] | Longitudinal | ELSA | · 6475 participants. · Community-dwelling. · 50 years or elderly. · Living in UK. · Without dementia at baseline. · Not outliers in subjective age (≥3 sd). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) Executive function (category fluency) Cognitive decline (self-reported) | No | Yes | Elderly subjective age reported at baseline predicted poorer memory (β = −0.70, p = 0.02) and executive function (β = −1.56, p < 0.01) ten years later after controlling for covariates. Elderly subjective age was a risk factor for dementia (HR = 1.737) after controlling for covariates. |

| Stephan et al., 2021 [75] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 6341 participants. ·65 years or elderly. ·Without dementia. · Excluding outliers on gait speed and subjective age. · 57% female. | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Cognitive decline (TICS) | No | Yes | Elderly subjective age participants were more likely to present MCR at baseline (OR = 4.44) and to develop MCR at follow-up (HR = 3.55). |

| Kisvetrová et al., 2021 [76] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · PwD: 290 participants; 60 years or elderly, community-dwelling, diagnosed early-stage dementia. · PwoD: 209 participants; 60 years or elderly. | Attitudes to aging (AAQ) | Cognitive decline (MMSE) | No | Yes | PwD scored lower on all subscales of AAQ: Psychosocial loss (p = 0.001), physical change (p = 0.001) and psychological growth (p = 0.001). |

| Levy et al., 2020 [77] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 3895 participants. · 490 APOE carriers. · 60 years or elderly at baseline. · APOE ε2: APOE probability score >0.8. · 50.17% female. · Mean age of 71.07 (sd = 6.76). | Age beliefs (PGCMS) | Global cognition (TICS) | No | Yes | Positive age beliefs (F = 122.68, p < 0.001) and APOE ε2 (F = 7.87, p = 0.005) predicted better cognition. The interaction of positive age beliefs and APOE ε2 significantly predicted cognition (F = 7.74, p = 0.005). |

| Wang et al., 2020 [78] | Cross-sectional | China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) | · 8723 participants. · 60 years or elderly. · Completed MMSE and ATOA. · 46.3% female. · Mean age of 69.82 (sd = 7.54). | Attitudes towards own aging (PGCMS) | Global cognition (MMSE) | ADLs and social network (Lubben scale) | No | There was a partial mediation effect since cognition predicted attitudes towards own aging (b = 0.355) and social support (b = 0.15), and social support predicted attitudes towards own aging (b = −0.31). |

| Hajek, 2020 [79] | Longitudinal | DEAS | · 6348 participants. · Community-dwelling. · 50% female. · Mean age of 65 (sd = 10.6). | Aging satisfaction (PGCMS) | Global cognition (SDMT) | No | Yes | Decreases in cognitive functioning were associated with decreases in satisfaction with aging (β = 0.002) after controlling for all covariates. |

| Siebert et al., 2020 [80] | Longitudinal | ILSE | · Midlife age: 40 years or elderly at baseline. Mean age of 43.7 (sd = 0.92). · Old age: 60 years or elderly at baseline. Mean age of 62.5. | Attitudes towards own aging (PGCMS) | Global cognition (SDMT, digit span and block design) | No | Yes | Participants with positive attitudes towards own aging showed higher cognitive ability in both midlife (b = 0.25, p < 0.001) and old group (b = 0.41, p < 0.001). After controlling for covariates, this effect only remained in the midlife group. |

| Shao et al., 2020 [81] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · 200 participants. · 60 years or elderly. · Complete measures. · No multivariate outliers. · Mean age of 65.42 (sd = 5.60). · 66.5% female. | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) | Learning self-efficacy and education (ad hoc) | Yes | Elderly subjective age was negatively associated with memory (r = −0.19). There was an indirect effect of subjective age on memory performance through learning self-efficacy (b = 0.04). There was an effect of elderly subjective age on learning self-efficacy (b = 0.18) and an interaction of subjective age and education on learning self-efficacy (b = 0.33). |

| Cerino et al., 2020 [82] | Cross-sectional | MIDUS | · 2621 participants. · 55.51%female. · Mean age of 64.06 (sd = 11.15). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) Executive function (TICS) | No | Yes | Reporting a more youthful subjective age was associated with better episodic memory (est.−0.10, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). |

| Choi et al., 2019 [23] | Cross-sectional | Dementia Literacy Survey | · 513 participants. · 60 years or elderly. · 55% female. · Mean age of 68.12 (sd = 5.65). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Global cognition (MMSE) | No | Yes | Subjective age correlated with cognitive functioning (r = 0.14, p = 0.01). In the full adjusted model, subjective age was a significant predictor of cognitive functioning (b = 0.08, p < 0.05). |

| Segel-Karpas & Palgi, 2022 [46] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 4624 participants. · 50 years or elderly at baseline. · Normal memory at baseline. · No dementia or stroke at follow-up. | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) | No | Yes | Subjective age correlated significantly with memory at t1 (r = −0.24, p < 0.001) and memory change (r = −0.15, p < 0.001). |

| Siebert et al., 2018 [83] | Longitudinal | ILSE | · T1: 1001 participants. Mean age of 62.5 (sd = 1). · T2 499 participants. Mean age of 66.6 (sd = 1.1). · T3 352 participants. Mean age of 74.3 (sd = 1.2). | Attitudes towards own aging (PGCMS) | Fluid intelligence (digit span, SDMT and block design) Crystallized intelligence (information, similarities, and picture completion) | No | Yes | After including covariables, more positive attitudes towards own aging baseline predicted less decline in fluid intelligence in men (βATOA = 0.71, p < 0.001) and explained 57% of the variance. However, it did not predict decline in women (βATOA = 0.7, p > 0.05). Positive attitudes did not predict less decline in crystallized intelligence. |

| Hughes & Lachman, 2017 [84] | Longitudinal | MIDUS | · 3427 participants. · Complete data in two waves. · Mean age of 55.92 (sd = 12.19). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) Executive function (digit span backwards, category fluency, stop and go, and number series) | Social comparison | Yes | Direct effects showed that episodic memory was significantly related to cross-sectional subjective age (b = −0.42, p < 0.01), and indirect effects indicated that social comparisons mediated it (b = −0.09, κ2 = 0.01). There were no significant direct effects between longitudinal changes of subjective age and episodic memory or executive function. |

| Buggle, 2018 [85] | Longitudinal | ELSA | · Responded to both waves 4 and 7 of ELSA. · Wave 4: 11,050 participants; 64.15% female, mean age of 64.19 (sd = 8.57). · Wave 7: 9666 participants; 69.78% female, mean age of 69.66 (sd = 8.04). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) Verbal fluency (category fluency and letter fluency) | No | Yes | Subjective age predicted immediate recall (β = −0.08; p < 0.001), delayed recall (β = −0.07; p < 0.001) and verbal fluency (β = −0.07; p < 0.001) at wave 4. Subjective age predicted immediate recall (β = −0.07; p < 0.001), delayed recall (β = −0.07; p < 0.001) and verbal fluency (β = −0.08; p < 0.001) at wave 7. Longitudinally, subjective age was a significant predictor of immediate recall (β = −0.03; p < 0.001), delayed recall (β = −0.03; p < 0.001) and verbal fluency (β = −0.01; p= 0.57). |

| Levy et al., 2018 [86] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 4756 participants. · 60 years or elderly at baseline. · No dementia at baseline. · APOE score >0.8. · Mean age of 72 years (sd = 7.19). | Age beliefs (PGCMS) | Cognitive decline (TICS) | No | Yes | Positive age beliefs were associated with lower risk of dementia in the total sample (RR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.67, 0.97, p = 0.03) and in the APOE ε4 sample (RR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.50, 0.94, p = 0.018). |

| Siebert et al., 2018 [87] | Longitudinal | ILSE | · 260 participants. · 60 years or elderly at baseline. · Cognitively healthy and without psychiatric disorders at baseline. | Attitudes towards own aging (PGCMS) | Cognitive decline (diagnosis or formal neuropsychological assessment) | Leisure activity and control beliefs | Yes | More negative ATOA at baseline was related to higher risk of MCI or AD at time 3 (b = 0.283, p < 0.05; OR 1.43). There was a significant path from ATOA to overall activity (b = 0.44, p < 0.001) but not from overall activity to future cognitive status. Adding cognitive leisure activity to the model weakened the direct effect of ATOA on cognitive status (b = 0.19, p = 0.09). There was a significant path from ATOA to external control beliefs (b = 0.17, p < 0.05) and external control beliefs to cognitive status at T3 (b = 0.15, p < 0.05) and a nonsignificant effect from ATOA to cognitive status (b = 0.18, p =0.08). |

| Stephan et al., 2018 [88] | Longitudinal | NHATS | · 4262 participants. · 65 years or elderly. · No dementia at baseline. · No subjective age outliers (≥3 sd). · Mean age of 76 (sd = 7.2). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Cognitive decline (diagnosis or formal neuropsychological assessment) | No | Yes | After controlling for demographics, depression and physical health, subjective age was not related to likelihood of developing dementia (HR = 1.11, p > 0.05). However, it was related in a subsample that excluded cases developed during the first year after the baseline measures (HR = 1.62, p < 0.05). |

| Tyrrell, 2017 [89] | Cross-sectional | HRS | · 361 participants. · 60 years or elderly. · 56% female. · Mean age of 73.67 (sd = 6.58). | Aging satisfaction (ad hoc) Aging expectations (ad hoc) | Memory (word recall) Language (vocabulary) | No | Yes | Aging satisfaction correlated with vocabulary (r = 0.12, p < 0.001) and memory (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), but it did not improve their predictive models (vocabulary: b = −0.004, p = 0.37; memory: b = 0.001, p = 0.73). Aging expectations correlated with vocabulary (r = 0.04, p < 0.001) and memory (r = 0.13, p < 0.001), but it did not improve their predictive models (vocabulary: b = −0.002, p = 0.11; memory: b = 0.000, p = 0.73). |

| Seidler & Wolff, 2017 [22] | Longitudinal | DEAS | · Baseline: 8198 adults. · Follow-up. · 49% female. · Mean age of 62.56 (sd = 11.93). | Self-perceptions of aging (Age-Cog) | Speed of processing (SDMT) | No | Yes | Physical loss (r = 0.24, p < 0.001) and personal growth (r = −0.17, p = 0.007) were correlated with speed of processing at baseline, but the cross-lagged paths of physical loss (Δχ2 = 0.12, p = 0.73; b = –0.03, p = 0.03) and personal growth (Δχ2 = 0.05, p = 0.83; b = 0.03, p = 0.01) on processing speed were equal without significant loss. |

| Stephan et al., 2017 [90] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 5772 participants. · 65 years or elderly at baseline. · No cognitive impairment at baseline. · No subjective age outliers (≥3 sd). · 59% female. · Mean age of 73.69 (sd = 6.24). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Cognitive decline (TICS) | No | Yes | An elderly subjective age at baseline was related to an increased likelihood of dementia (OR = 1.27, p < 0.001) and cognitive impairment (TICS-m <12: OR = 1.16, p < 0.001; TICS 7–11: OR 1.15, p < 0.001) after controlling for covariates, time interval, and baseline cognition. |

| Jaconelli et al., 2017 [91] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · Dementia group: · France: 49 participants diagnosed with mild-to-moderate dementia of Alzheimer’s type aged 73–93 years old (MoCA: mean = 15.96, SD = 3.60). · US: 30 participants with dementia aged 77–82 years (MoCA: mean = 10.70, SD = 5.11). · Control group: 31 participants. No dementia; 60 years or elderly. | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Cognitive decline (MoCA) | No | Yes | France: No significant difference in subjective age between the dementia and control groups after controlling for covariates (F = 0.06, p = 0.80). US: No significant difference in subjective age between the dementia and control groups after controlling for covariates (F(1, 54) = 0.56, p = 0.46). Both subsamples: No significant difference in subjective age between the dementia and control groups after controlling for covariates (d = 0.03; p > 0.05). |

| Robertson & Kenny, 2016 [92] | Cross-sectional | TILDA | · 4135 participants. · 50 years or elderly. · Community-dwelling. · No dementia, antidepressants, dementia medication or stroke history. · 53.4% female. · Mean age of 62 (sd = 8.7). | Self-perceptions of aging (B-APQ) | Global cognition (MMSE and MoCa) Executive function (visual reasoning, TMT-B and category fluency) Memory (picture recall) Attention (TMT-A) | No | Yes | Negative perceptions were a significant predictor of global cognition (B = −0.09, p < 0.05), executive function (B = −0.12, p < 0.001) and memory (B = −0.11, p < 0.01) but not attention (B = 0.03, p > 0.05). |

| Robertson et al., 2016 [93] | Longitudinal | TILDA | · 5896 participants. · 50 years or elderly at baseline. · Community-dwelling. · No stroke, Parkinson’s disease, MMSE < 18 or suspected dementia at baseline or in the intervening 2 years between waves. · 54.65% female. · Mean age of 63.17 (sd = 9.36). | Self-perceptions of aging (B-APQ) | Verbal fluency (category fluency) Memory (word recall and prospective memory) | No | Yes | Cross-sectional: Verbal fluency was associated with positive control (IRR = 0.38, p < 0.01) and negative control and consequences (IRR = −0.33, p < 0.05). Delayed memory was associated with positive control (IRR = 0.12, p < 0.01) and negative control and consequences (IRR = −0.21, p < 0.01). Immediate memory was associated with timeline (IRR = −0.13, p < 0.05), positive consequences (IRR = 0.12, p < 0.05), positive control (IRR = 0.15, p < 0.05) and negative consequences and control (IRR = −0.22, p < 0.01). · Longitudinal: Positive control was associated with animal naming in wave 2 (B = 0.43, p < 0.001). Negative control and consequences were associated with animal naming in wave 2 (B = −0.51, p < 0.001). Timeline was associated with the first prospective memory task (IRR = 0.98, p < 0.05). |

| Jung, 2016 [94] | Longitudinal | DEAS | · 2545 middle-aged participants (age between 40 and 64 years). ·1489 old participants (65 years or elderly). | Self-perceptions of aging (PEAS) | Global cognition (SDMT) | No | Yes | · Physical loss predicted changes in cognitive performance in the middle-aged group (T1→T2: –0.12, p < 0.01 and T3→T4: –0.12, p < 0.01) and the old group (T1→T2: –0.17, p < 0.01; T3→T4: –.26, p < 0.05). Cognitive performance only predicted changes in physical loss in the old group (T2→T3: –0.22, p < 0.05). · Social loss did not predict changes in cognitive performance in the middle-aged group, but it did in the old group (T1→T2: –0.30, p < 0.01; T3→T4: –0.40, p < 0.01). Moreover, cognitive performance predicted changes in social loss in the old group (T3 to T4: –0.51, p < 0.01). · Continuous growth predicted changes in cognitive performance in the middle-aged group (T1→T2:.13, p < 0.01) and the old group (T1→T2: 0.23, p < 0.01). Cognitive performance only predicted changes in continuous growth in the middle-aged group (T2→T3: 0.10, p < 0.05). |

| Stephan et al., 2016 [95] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 5809 participants at baseline; 3631 participants with complete data. · 50 years or elderly at baseline. · No subjective age outliers (= + 3 sd). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) | No | Yes | A younger subjective age at baseline was related to better immediate recall (β = 0.05, p < 0.001), delayed recall (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) and total memory (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) at baseline, and with better immediate recall (β = 0.04, p < 0.001), delayed recall (β = 0.03, p < 0.01) and total memory (β = 0.04, p < 0.001) longitudinally. Depressive symptoms mediated the association between subjective age and changes in immediate recall (β = 0.04, p < 0.001), delayed recall (β = 0.05, p < 0.001) and total memory (β = 0.08, p < 0.001). |

| Hagood & Gruenewald, 2015 [96] | Longitudinal | HRS | ·1518 participants · Age between 65 and 99. | Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) | Memory (word recall) | No | No | Negative self-perceptions of aging are related to reductions of memory over time (β = −0.26; p < 0.001) after controlling for covariables. |

| Hülür et al., 2015 [97] | Longitudinal | HRS | · 5824 participants at T1. · 50 years or elderly. · 58% female. · Mean age of 64.27 (sd = 9.9). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) | No | No | Subjective age predicted correlated with memory at baseline (r = −0.31; p < 0.01) but did not improve the predictive model (b = −0.01, p > 0.01). |

| Ihira et al., 2015 [98] | Cross-sectional | Population-based and Inspiring Potential Activity for Old-old Inhabitants (PIPAOI) study | · 275 participants. · 75 years or elderly. · No recent hospitalization, stroke, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, dementia, depression, or schizophrenia. · 59.1% female. · Mean age of 80 (sd = 4.1). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Attention (TMT-A) Executive function (TMT-B) Speed of processing (SDMT) Memory (word recall) | No | Yes | Subjective cognitive age correlated with attention (r = 0.12, p < 0.01), executive function (r = 0.18, p < 0.01), speed of processing (r = −0.29, p < 0.01) and memory (r = −0.25, p < 0.01). Subjective physical age only correlated with speed of processing (r = −0.25, p < 0.01). Word list score was a significant predictor of subjective cognitive age (OR = 1.26, p = 0.03). |

| Chasteen et al., 2015 [99] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · 301 elderly adults. · 63.78% female. · Mean age of 71.13 (sd = 7.4). | Views of aging (ARS) | Memory (word recall) | No | No | There was no correlation between views of aging and memory (r = −0.07, p > 0.05). |

| Shenkin et al., 2014 [100] | Longitudinal | Lothian Birth Cohort (1936) | · 1091 participants. · Community-dwelling. | Attitudes to aging (AAQ) | Fluid intelligence (letter number, digit span backwards, matrix reasoning, block design, SDMT and symbol search) Global cognition (MMSE) | No | Yes | Fluid intelligence correlated with the psychosocial loss (r = −0.13, p < 0.001) and physical change (r = 0.127, p < 0.001) subscales of the AAQ. Fluid intelligence did not predict scores of psychosocial loss (b = −0.014, p > 0.05), physical change (b = 0.068, p > 0.05) or psychological growth (b = 0.009, p > 0.05) subscales of the AAQ. |

| Stephan et al., 2014 [101] | Longitudinal | MIDUS | · 1368 participants. · 50 years or elderly at baseline. · Without neurological disorders. · 76% female. · Mean age of 59.95 (sd = 6.73). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) Executive function (digit span backwards, category fluency, stop and go, and number series) | Body mass index and physical function | Yes | · Subjective age correlated significantly with episodic memory (r = 0.06, p < 0.05) and executive function (r = 0.06, p < 0.05). Subjective age was a significant predictor of episodic memory (b = 0.05, p < 0.05) and executive function (b = 0.05, p < 0.05). BMI partially mediated the relationship between subjective age and episodic memory (indirect effect b = 0.07). Physical activity partially mediated the relationship between subjective age and executive function (indirect effect b = 0.02). |

| Hughes, 2014 [102] | Cross-sectional | 1A and 1B: Own sample, non-randomized. 1C: MIDUS | · 1A: 47 participants. Scores equal to or higher than 26 at MMSE; 65 years or elderly; 53.17% female. Mean age of 71.4 (sd = 7.1). · 1B: 78 participants. Scores equal to or higher than 26 at MMSE; 55 years or elderly. Mean age of 59.87 (sd = 4.21). · 1C: 3228 participants; 54.3% female. Mean age of 55.92 (sd = 12.16). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Memory (word recall) Language (vocabulary) Speed of processing (lexical decision and backwards count) Working memory (digit span and digit span backwards) Verbal fluency (category exemplar and category fluency) Reasoning (number series) Attention (backwards count) | No | Yes | 1A: No correlations between subjective age and cognitive indicators after controlling for chronological age. Applying bootstrap, it was correlated with recall (r = 0.11, p = 0.00), vocabulary (r = 0.07, p = 0.03), category fluency (r = −0.13, p = 0.00), F-A-S perseverative errors (r = −0.09, p = 0.01) and category fluency perseverative errors (r = −0.11, p = 0.00). 1B: Baseline subjective age was correlated with reasoning ability after controlling for chronological age (r = −0.26, p = 0.02). Applying bootstrap, subjective age correlated with processing speed (r = 0.07, p = 0.03), reasoning ability (r = −0.14, p = 0.00), category fluency (r = −0.10, p = 0.00), LDT prediction (r = −0.13, p = 0.00), reasoning ability prediction (r = 0.13, p = 0.00) and vocabulary prediction (r = −0.14, p = 0.00). 1C: Baseline subjective age correlated with immediate recall (r = −0.09, p = 0.00), delayed recall (r = −0.09, p = 0.00), the proportion of forgotten words between the two recall tests (r = 0.05, p = 0.03), processing speed (r = −0.06, p = 0.00), working memory (r = −0.06, p = 0.01), reasoning ability (r = −0.05, p = 0.03) and category fluency (r = −0.07, p = 0.00). |

| Levy et al., 2012 [103] | Longitudinal | BLSA | · 1st hypothesis: 395 participants. Community-dwelling. At least 22 years old at baseline; 28.6% female. Mean age of 45 years at baseline. · 2nd hypothesis: 87 participants. Measure of self-relevance; 40 years or elderly; 31.03% female. Mean age of 53 years at baseline. | Age stereotypes (PGCMS) Self-relevance (ad hoc) | Memory (picture recall) | No | Yes | After controlling for covariates, there was a link between age stereotypes and memory over time (b = −0.24, p = 0.04, d = 2) that increased as the participants aged. Moreover, there was a significant interaction between age stereotypes and self-relevance on memory (B = −31.10, p = 0.0002, d = 3.7). |

| Sindi, 2014 [104] | Cross-sectional | Douglas Hospital Longitudinal Study of Normal and Pathological Aging | · 40 participants. · With no history of head trauma, cerebral vascular accident, alcohol abuse, use of medications or use of anesthesia in the previous year. · Cognitively healthy. · 55% female. · Mean age of 71.25 (sd = 1.39). | Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) | Memory (paired learning) | No | Yes | Self-perceptions of aging did not predict total related (p = 0.718) nor total unrelated (p = 0.544) word pairs recall. |

| Trigg et al., 2012 [105] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | ·PwD: 56 participants. Mild dementia. · PwoD: 84 participants; 60 years or elderly. Community-dwelling. Cognitively healthy. | Attitudes to aging (AAQ) | Cognitive decline (MoCA) | No | No | There were significant differences in the psychosocial loss subscale of the AAQ (t = 3.56, p < 0.01). |

| Paggi et al., 2011 [106] | Cross-sectional | ILSE | · Middle-aged: 501 participants. Mean age of 44.2. · Elderly: 499 participants. Mean age of 62.9. | Self-perceptions of aging (PGCMS) | Reasoning (block design, spatial capacity and picture completion) Speed of processing (D2, SDMT and connect the numbers) Memory (digit span, word recall and picture recall) | No | No | Aging self-perceptions were not related to speed of processing (Es = 0.02, p > 0.05), memory (Es = 0.02, p > 0.05) or reasoning (Es = 0.00, p > 0.05) in the middle-aged sample. Aging self-perceptions were related to memory (Es = 0.07, p < 0.05) and reasoning (Es = 0.09, p < 0.05) in the elderly adults sample, but processing speed did not mediate this relationship. |

| Lee & Hong, 2010 [107] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · 1345 participants. · 60 years or elderly. · Without cognitive impairment. · 74.02% female. · Mean age of 75.8 (sd = 6.2). | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Global cognition (MoCA) | No | Yes | There was a significant difference in the estimated marginal means of MMSE among 4 quartile groups after controlling for covariates (F = 13.122, p < 0.0001). Subjective age was associated with general cognition in the elderly after adjusting for covariates (b = 0.116, p < 0.0001). |

| Murphy, 2009 [108] | Longitudinal | MIDUS and BOLOS | · MIDUS: 4955 participants at follow-up; 53.34% female. Mean age of 55.45 (sd = 12.44). · BOLOS: 151 participants at follow-up; 38.41% female. Mean age of 46.57. | Subjective age (composite score of age discrepancy) Look age (composite score of age discrepancy) | Global cognition (BTACT) | No | Yes | The young feel age group obtained higher scores in cognition (F = 17.09, p < 0.001) when compared with the same and old feel age group. |

| Levy & Langer, 1994 [109] | Cross-sectional | Non-random | · 90 participants. · From the American deaf, American hearing and Mainland China. · Participants were 45 young adults (mean age = 22) and 45 elderly adults (mean age = 70). | Attitudes to aging (FAQ) | Memory (picture recall and paired learning) | No | Yes | There was a significant correlation between views of aging and memory in the old group (r = 0.49, p < 0.01). The direct path between views of aging and memory was significant (ES = −0.31, p < 0.001). The direct path between positive culture and memory was not significant (p > 0.05). The direct paths between age and memory and age and positive age views were not significant (p > 0.05). |

| Cognitive Domain | Subjective Aging Construct | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Age | SPA | ATOA | Attitudes to Aging | Awareness of Age-Related Change | Age Beliefs | Views of Aging | Aging Satisfaction | Age Stereotypes | Aging Expectations | Age Identification | Look Age | |

| Memory | 16 (15) | 9 (6) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |||

| Global cognition | 6 (3) | 6 (5) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | |||

| Cognitive decline | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | ||||||||

| Speed of processing | 3 (3) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) | ||||||||

| Executive functions | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Reasoning | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (3) | |||||||||

| Attention | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | ||||||||||

| Language | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |||||||||

| Fluid intelligence | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |||||||||

| Crystallized intelligence | 1 (0) | 2 (0) | ||||||||||

| Visuospatial | 2 (1) | |||||||||||

| Working memory | 2 (2) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | |||||||||

| Verbal fluency | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | ||||||||||

| Speed–attention–executive | 1 (1) | |||||||||||

| Total | 50 (35) | 26 (16) | 8 (5) | 7 (6) | 10 (7) | 3 (3) | 3 (0) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Domain | N of Studies Included | Measure | N of Times Employed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | 29 | ||

| Word recall | 24 | ||

| Picture recall | 4 | ||

| Brave Man | 2 | ||

| Digit span | 1 | ||

| Paired learning | 4 | ||

| Prospective memory task | 1 | ||

| Logical memory | 1 | ||

| Global cognition | 17 | ||

| MMSE | 8 | ||

| SDMT | 3 | ||

| TICS | 2 | ||

| Digit span | 2 | ||

| MoCA | 2 | ||

| Self-ordered search | 1 | ||

| Grammatical reasoning | 1 | ||

| BTACT | 1 | ||

| Block design | 1 | ||

| DemTect | 1 | ||

| Cognitive decline | 11 | ||

| TICS | 6 | ||

| MMSE | 3 | ||

| Diagnosis or formal neuropsychological assessment | 2 | ||

| MoCA | 1 | ||

| Self-reported | 1 | ||

| Speed of processing | 7 | ||

| SDMT | 6 | ||

| Backwards count | 2 | ||

| TMT-A | 1 | ||

| Letter cancellation | 1 | ||

| D2 | 1 | ||

| Executive function | 7 | ||

| Category fluency | 4 | ||

| Number series | 3 | ||

| TMT-B | 3 | ||

| Number series | 3 | ||

| Digit span (backwards) | 2 | ||

| Stop and go | 2 | ||

| TICS | 1 | ||

| Visual reasoning | 1 | ||

| Reasoning | 6 | ||

| Number series | 3 | ||

| Block design | 1 | ||

| Spatial capacity | 1 | ||

| Picture completion | 1 | ||

| Grammatical reasoning | 1 | ||

| Letter series | 1 | ||

| Number comparison | 1 | ||

| Verbal fluency | 4 | ||

| Category fluency | 4 | ||

| Letter fluency | 1 | ||

| Attention | 3 | ||

| TMT-A | 2 | ||

| Backwards count | 1 | ||

| Language | 3 | ||

| Vocabulary | 2 | ||

| Naming | 1 | ||

| Category fluency | 1 | ||

| Fluid intelligence | 3 | ||

| SDMT | 3 | ||

| Block design | 3 | ||

| Digit span (backwards) | 1 | ||

| Digit span | 1 | ||

| Letter-number | 1 | ||

| Visual reasoning | 1 | ||

| Symbol search | 1 | ||

| Crystallized intelligence | 2 | ||

| Information | 2 | ||

| Similarities | 2 | ||

| Picture completion | 2 | ||

| Visuospatial | 2 | ||

| Constructional praxis | 3 | ||

| Visual reasoning | 1 | ||

| Working memory | 2 | ||

| Digit span | 2 | ||

| Self-ordered search | 1 | ||

| Digit span (backwards) | 1 | ||

| Speed–attention–executive | 1 | ||

| Letter cancellation | 1 | ||

| SDMT | 1 | ||

| TMT-A | 1 | ||

| TMT-B | 1 | ||

| Stop and go | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Ballbé, Ó.; Martin-Moratinos, M.; Saiz, J.; Gallardo-Peralta, L.; Barrón López de Roda, A. The Relationship between Subjective Aging and Cognition in Elderly People: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243115

Fernández-Ballbé Ó, Martin-Moratinos M, Saiz J, Gallardo-Peralta L, Barrón López de Roda A. The Relationship between Subjective Aging and Cognition in Elderly People: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(24):3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243115

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Ballbé, Óscar, Marina Martin-Moratinos, Jesus Saiz, Lorena Gallardo-Peralta, and Ana Barrón López de Roda. 2023. "The Relationship between Subjective Aging and Cognition in Elderly People: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 11, no. 24: 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243115

APA StyleFernández-Ballbé, Ó., Martin-Moratinos, M., Saiz, J., Gallardo-Peralta, L., & Barrón López de Roda, A. (2023). The Relationship between Subjective Aging and Cognition in Elderly People: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 11(24), 3115. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243115