Using the Expanded Andersen Model to Determine Factors Associated with Mexican Adolescents’ Utilization of Dental Services

Abstract

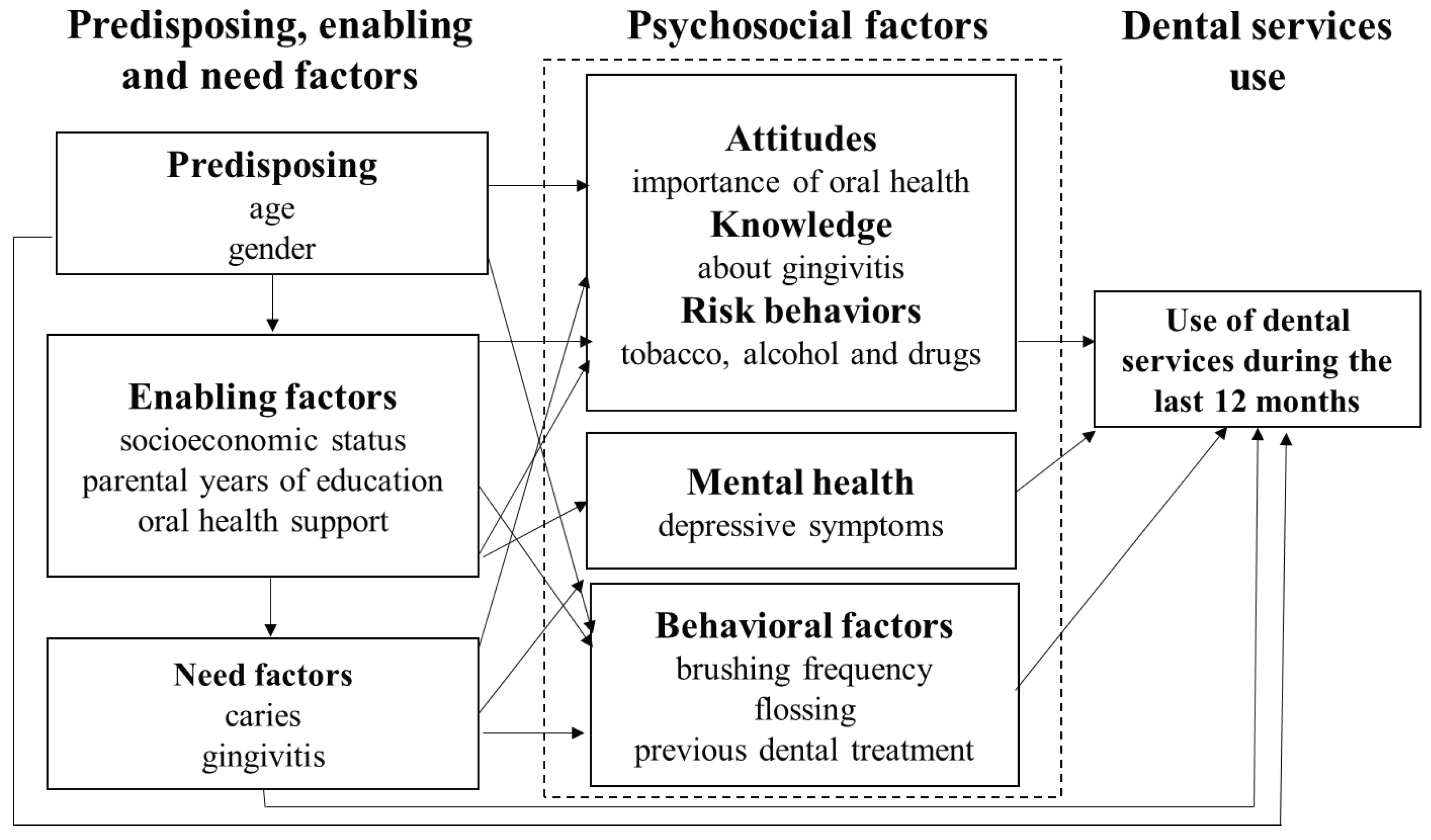

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Use of Dental Services

3.2. Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors

3.3. Psychosocial Factors and Behavioral Factors

3.4. Bivariate Associations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Secretaría del Trabajo y Previsión Social Gobierno de México. Observatorio Laboral 2023. Available online: https://www.observatoriolaboral.gob.mx/#/carrera/carrera-detalle-nacional/5713/33/Estomatolog%C3%ADa%20y%20odontolog%C3%ADa/Nacional/ (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Secretaría de Salud Gobierno de México. Programa de Acción Específico de Prevención, Detección y Control de las Enfermedades Bucales. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/706942/PAE_BUC_cF.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. Encuesta Nacional de Salud en Escolares 2008. 2010. Available online: https://www.insp.mx/images/stories/Produccion/pdf/101202_ense.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Galicia-Diez Barroso, D. Asociación Entre Soporte Social y el Estado de Salud Bucal en Estudiantes del Colegio de Bachilleres Plantel No. 4 “Culhuacán”. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Proyecto de Estrategia Mundial Sobre Salud Bucodental 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/18-11-2022-who-highlights-oral-health-neglect-affecting-nearly-half-of-the-world-s-population (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Salud Bucodental 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Masood, Y.; Masood, M.; Zainul, N.N.B.; Araby, N.B.A.A.; Hussain, S.F.; Newton, T. Impact of malocclusion on oral health related quality of life in young people. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivara, F.; Park, M.J.; Irwin, C.E., Jr.; DiClemente, R.; Santelli, J.; Crosby, R. Trends in Adolescent and Young Adult Morbidity and Mortality. Adolescent Health: Understanding and Preventing Risk Behaviors; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; p. 7Á29. [Google Scholar]

- Gaete, V. Adolescent psychosocial development. Rev. Chil. Pediatría 2015, 86, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, R.; Newman, J.F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in theUnited States. Milbank Meml. Fund Q. Health Soc. 1973, 51, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E.H.; McGraw, S.A.; Curry, L.; Buckser, A.; King, K.L.; Kasl, S.V.; Andersen, R. Expanding the Andersen model: The role of psychosocial factors in long-term care use. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 37, 1221–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AEFCM, Estadísticas: Primarias y Secundarias Generales, Ciclo Escolar 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.aefcm.gob.mx/inf_sep_cdmx/estadisticas/ei2018_2019.html (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Asociación Mexicana de Agencias de Investigación de Mercado y Opinión Pública. Niveles Socioeconómicos AMAI. 2018. Available online: https://www.amai.org/NSE/ (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Asociación Mexicana de Agencias de Investigación de Mercado y Opinión Pública. Descripción de los Niveles Socioeconómicos 2018. Available online: https://www.amai.org/NSE/index.php?queVeo=niveles (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Mariño, M.; Medina-Mora, M.; Chaparro, J.; González-Forteza, C. Confiabilidad y estructura factorial del CES-D en adolescentes mexicanos. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 1993, 10, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, A.I.; Sohn, W.; Tellez, M.; Amaya, A.; Sen, A.; Hasson, H.; Pitts, N.B. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS): An integrated system for measuring dental caries. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Weijden, G.; Timmerman, M.; Nijboer, A.; Reijerse, E.; Van der Velden, U. Comparison of different approaches to assess bleeding on probing as indicators of gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1994, 21, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Encuestas de Salud Bucodental. Métodos Básicos. Malta 1997. Updated 1997. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/41997/9243544934_spa.pdf;jsessionid=5D939DA1F66C66AC80B4DE80BCB79996?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Stella, M.Y.; Bellamy, H.A.; Schwalberg, R.H.; Drum, M.A. Factors associated with use of preventive dental and health services among US adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2001, 29, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R.; Baelum, V. Factors associated with dental attendance among adolescents in Santiago, Chile. BMC Oral Health 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, E.P.d.; Frias, A.C.; Mialhe, F.L.; Pereira, A.C.; Meneghim, M.d.C. Factors associated with last dental visit or not to visit the dentist by Brazilian adolescents: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldani, M.H.; Mendes, Y.B.; Lawder, J.A.; de Lara, A.P.; Rodrigues, M.M.; Antunes, J.L. Inequalities in dental services utilization among Brazilian low-income children: The role of individual determinants. J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahouraii, H.; Wasserman, M.; Bender, D.E.; Rozier, R.G. Social support and dental utilization among children of Latina immigrants. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlan, R.; Ghazal, E.; Saltaji, H.; Salami, B.; Amin, M. Impact of social support on oral health among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S. Factors affecting dental anxiety and beliefs in an Indian population. J. Oral Rehabil. 2008, 35, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.M.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhi, Q.H.; Lin, H.C. The relationship between children’s oral health-related behaviors and their caregiver’s social support. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yuan, B.; Zhou, S.; Peng, S.; Xu, Y.; Cai, H.; Cheng, L.; You, Y.; Hu, T. Socio-demographic factors, dental status, oral health knowledge and attitude, and health-related behaviors in dental visits among 12-year-old Shenzhen adolescents: A multilevel analysis. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronis, D.L.; Lang, W.P.; Farghaly, M.M.; Passow, E. Tooth brushing, flossing, and preventive dental visits by Detroit-area residents in relation to demographic and socioeconomic factors. J. Public Health Dent. 1993, 53, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, S.S.; Knuuttila, M.L.; Sakki, T.K. Relationship of depressive symptoms to edentulousness, dental health, and dental health behavior. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2001, 59, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Ziebolz, D.; Zeynalova, S.; Löffler, M.; Stengler, K.; Wirkner, K.; Haak, R. Dental and Medical Service Utilisation in a German Population - Findings of the LIFE-Adult-Study. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2020, 18, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stockbridge, E.L.; Dhakal, E.; Griner, S.B.; Loethen, A.D.; West, J.F.; Vera, J.W.; Nandy, K. Dental visits in Medicaid-enrolled youth with mental illness: An analysis of administrative claims data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drilea, S.K.; Reid, B.C.; Li, C.-H.; Hyman, J.J.; Manski, R.J. Dental visits among smoking and nonsmoking US adults in 2000. Am. J. Health Behav. 2005, 29, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, W.J.; Locker, D. Smoking and oral health status. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 155. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Utilization of Dental Services in the Last 12 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 122) | Yes (n = 125) | Total (n = 247) | p | |

| Predisposing factors | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 13.56 (1.15) | 13.45 (1.02) | 13.51 (1.09) | 0.46 * |

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Male | 67 (54.92) | 52 (41.60) | 119 (48.18) | 0.036 ** |

| Female | 55 (45.08) | 73 (58.40) | 128 (51.82%) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Enabling factors | ||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 157.78 (55.11) | 171.56 (52.13) | 164.76 (53.96) | 0.045 * |

| Mothers’ years of education | No (n = 113) | Yes (n = 115) | Total (n = 228) | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.06 (3.81) | 9.93 (3.53) | 9.50 (3.69) | 0.07 * |

| Fathers’ years of education | No (n = 103) | Yes (n = 103) | Total (n = 206) | |

| Mean (SD) | 8.96 (3.29) | 9.92 (3.83) | 9.44 (3.59) | 0.055 * |

| Oral health support | ||||

| With support | 75 (61.48) | 107 (85.60) | 182 (73.68) | 0.001 ** |

| Without support | 47 (38.52) | 18 (14.40) | 65 (26.32) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Need factors | ||||

| Caries | Yes (n = 98) | No (n = 106) | Total (n = 204) | |

| Yes | 54 (55.10) | 67 (63.21) | 121 (59.31) | 0.24 ** |

| No | 44 (44.90) | 39 (36.79) | 83 (40.69) | |

| Total | 98 (100) | 106 (100) | 204 (100) | |

| Gingivitis | Yes (n = 98) | No (n = 106) | Total (n = 204) | |

| Yes | 95 (96.94) | 102 (96.23) | 197 (96.57) | 0.78 ** |

| No | 3 (3.06) | 4 (3.77) | 7 (3.43) | |

| Total | 98 (100) | 106 (100) | 208 (100) | |

| Psychosocial and behavioral factors | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.95 (11.49) | 18.38 (10.38) | 20.14 (11.06) | 0.012 *** |

| Median (IQR) | 20.50 (19) | 16 (15) | 17 (28) | |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 65 (53.28) | 54 (43.20) | 119 (48.20) | 0.11 ** |

| No | 57 (46.72) | 71 (56.80) | 128 (51.82) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Tobacco | ||||

| Yes | 42 (34.43) | 25 (20.00) | 67 (27.13) | 0.01 ** |

| No | 80 (65.57) | 100 (80.00) | 180 (72.87) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Drugs | ||||

| Yes | 20 (16.39) | 13 (10.40) | 33 (13.36) | 0.17 ** |

| No | 102 (83.61) | 112 (89.60) | 214 (86.64) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Psychosocial and behavioral factors | ||||

| Brushing frequency | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.36 (0.99) | 2.49 (0.78) | 2.42 (0.89) | 0.10 *** |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Flossing | ||||

| Yes | 27 (22.13) | 59 (47.20) | 86 (34.82) | 0.001 ** |

| No | 95 (77.87) | 66 (52.80) | 161 (65.18) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Knowledge of gingivitis | ||||

| Not suitable | 92 (75.41) | 96 (76.80) | 188 (76.11) | 0.79 ** |

| Suitable | 30 (24.59) | 29 (23.20) | 59 (23.89) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Attitude towards the importance of oral health | ||||

| Adequate | 16 (13.11) | 26 (20.80) | 42 (17.00) | 0.10 ** |

| Inadequate | 106 (86.89) | 99 (79.20) | 205 (83.00) | |

| Total | 122 (100) | 125 (100) | 247 (100) | |

| Presence of previous dental treatment | ||||

| Yes | 21 (21.43) | 45 (42.45) | 66 (32.35) | 0.001 ** |

| No | 77 (78.57) | 61 (57.55) | 138 (67.65) | |

| Total | 98 (100) | 106 (100) | 204 (100) | |

| Variables | Crude OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | ||||

| Age | 0.91 (0.72–1.14) | 0.43 | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) | 0.86 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.71 (1.03–2.83) | 0.03 | 1.39 (0.73–2.66) | 0.31 |

| Enabling factors | ||||

| SES | 1.004 (1.01–1.01) | 0.04 | 1.01 (0.99–1.01) | 0.09 |

| Oral health support | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 3.72 (2.01–6.91) | 0.001 | 2.69 (1.24–5.84) | 0.012 |

| Mothers’ years of education | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 0.07 | - | - |

| Fathers’ years of education | 1.07 (0.99–1.17) | 0.05 | - | - |

| Need factors | ||||

| Caries | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.39 (0.79–2.45) | 0.24 | 1.78 (0.91–3.46) | 0.08 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.012 | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.03 |

| Tobacco use once in life | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 2.1 (1.18–3.73) | 0.012 | 2.19 (0.99–4.86) | 0.05 |

| Alcohol use once in life | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 1.49 (0.91–2.48) | 0.11 | - | - |

| Drug use once in life | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 1.69 (0.79–3.57) | 0.17 | - | - |

| Drug use once in life | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 1.69 (0.79–3.57) | 0.17 | - | - |

| Brushing frequency | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 0.23 | 1.24 (0.86–1.80) | 0.24 |

| Flossing | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 3.14 (1.81–5.47) | 0.001 | 1.87 (0.94–3.71) | 0.07 |

| Attitude towards the importance of oral health | ||||

| Inadequate | 1 | |||

| Adequate | 1.74 (0.88–3.43) | 0.11 | 1.69 (0.69–4.17) | 0.24 |

| Previous dental treatment | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 2.7 (1.46–5.02) | 0.002 | 2.25 (1.12–4.52) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galicia-Diez Barroso, D.; Abeijón-Malvaez, L.D.; Moreno Altamirano, G.A.; Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E.J.; Finlayson, T.L.; Borges-Yáñez, S.A. Using the Expanded Andersen Model to Determine Factors Associated with Mexican Adolescents’ Utilization of Dental Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3159. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243159

Galicia-Diez Barroso D, Abeijón-Malvaez LD, Moreno Altamirano GA, Irigoyen-Camacho MEJ, Finlayson TL, Borges-Yáñez SA. Using the Expanded Andersen Model to Determine Factors Associated with Mexican Adolescents’ Utilization of Dental Services. Healthcare. 2023; 11(24):3159. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243159

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalicia-Diez Barroso, Daniela, Luis David Abeijón-Malvaez, Gloria Alejandra Moreno Altamirano, María Esther Josefina Irigoyen-Camacho, Tracy L. Finlayson, and Socorro Aída Borges-Yáñez. 2023. "Using the Expanded Andersen Model to Determine Factors Associated with Mexican Adolescents’ Utilization of Dental Services" Healthcare 11, no. 24: 3159. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243159

APA StyleGalicia-Diez Barroso, D., Abeijón-Malvaez, L. D., Moreno Altamirano, G. A., Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E. J., Finlayson, T. L., & Borges-Yáñez, S. A. (2023). Using the Expanded Andersen Model to Determine Factors Associated with Mexican Adolescents’ Utilization of Dental Services. Healthcare, 11(24), 3159. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11243159