Factors Associated with the Choice of Contraceptive Method following an Induced Abortion after Receiving PFPS Counseling among Women Aged 20–49 Years in Hunan Province, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

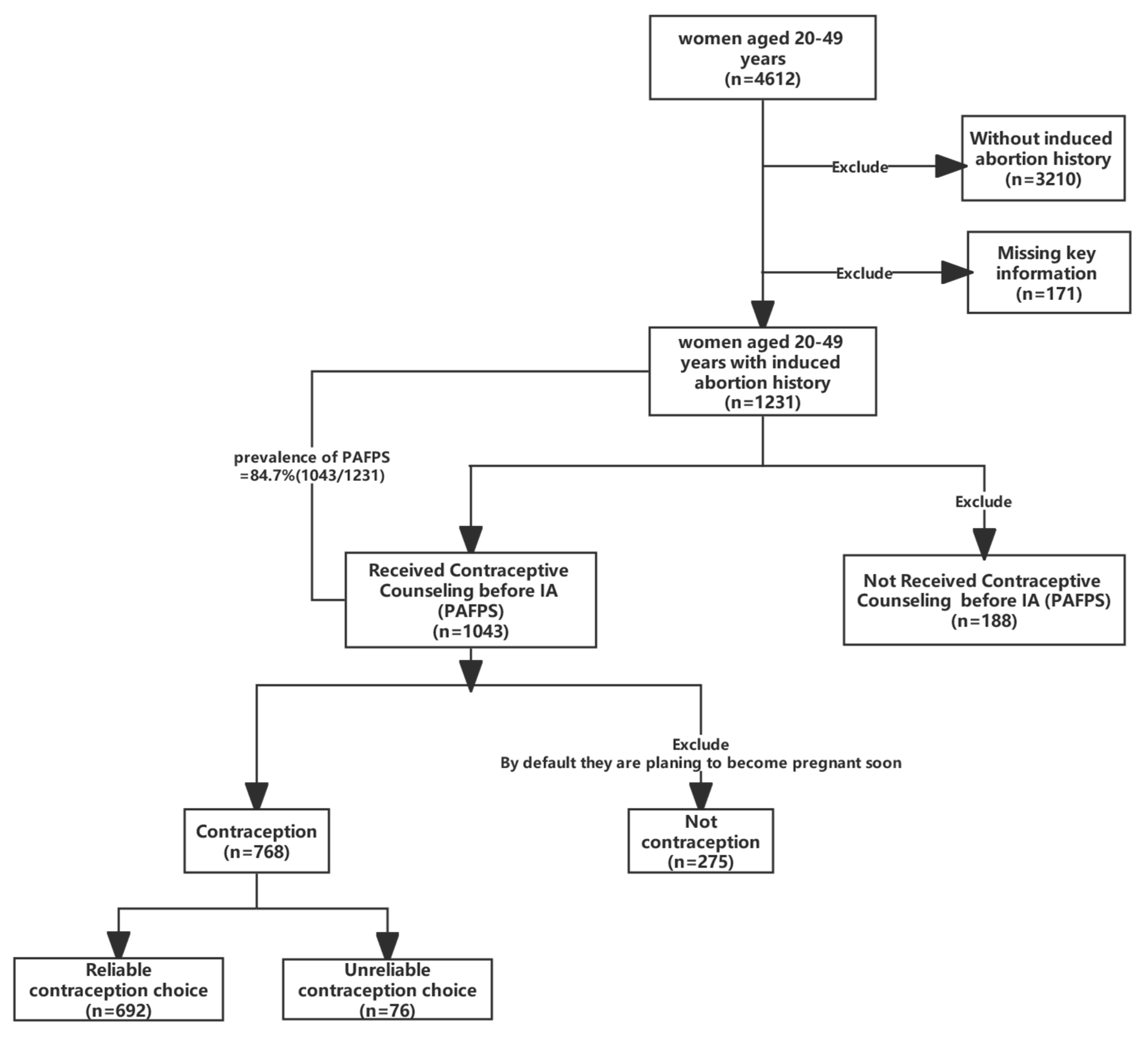

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.2.2. Contraceptive Methods

2.2.3. Factors Associated with PAFP Services

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Contraceptive Methods

3.2. Characteristics of the Participants

3.3. PAFP Services

3.4. Factors Associated with Contraception Choice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Moller, A.B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Beavin, C.; Kwok, L.; Alkema, L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1152–e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, M.R.; Turner, K.L. Essential elements of postabortion care: Origins, evolution and future directions. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2003, 29, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmerman, M. Missed opportunities in women’s health: Post-abortion care. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, A.; Ertem, M.; Saka, G.; Akdeniz, N. Post abortion family planning counseling as a tool to increase contraception use. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savelieva, I.; Pile, J.M.; Sacci, I.; Loganathan, R. Postabortion Family Planning Operations Research Study in Perm, Russia; Population Council, 2003; Available online: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/455 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Owolabi, O.O.; Biddlecom, A.; Whitehead, H.S. Health systems’ capacity to provide post-abortion care: A multicountry analysis using signal functions. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e110–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, S. What post-abortion care indicators don’t measure: Global abortion politics and obstetric practice in Senegal. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 254, 112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, A.Y.; Gu, X.Y.; Cheng, L.N. Guide to post-abortion family planning services. Chin. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 319–320. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.-H.; Li, J.; Che, Y.; Wu, S.; Qian, X.; Dong, X.; Xu, J.; Hu, L.; Tolhurst, R.; Temmerman, M. Effects of post-abortion family planning services on preventing unintended pregnancy and repeat abortion (INPAC): A cluster randomised controlled trial in 30 Chinese provinces. Lancet 2017, 390, S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y. Application effect of caring after caring for family planning care after artificial abortion. China Mod. Med. 2020, 27, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; He, N.; Du, Y.; Ding, J.X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.-T.; Huang, J.; Hua, K.-Q. Evaluation of two intervention models on contraceptive attitudes and behaviors among nulliparous women in Shanghai, China: A clustered randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission. China Health Care Statistics Yearbook; China Union Medical University Press: Beijing, China, 2019; p. 227.

- Tang, L.; Wu, S.; Liu, D.; Temmerman, M.; Zhang, W.H. Repeat Induced Abortion among Chinese Women Seeking Abortion: Two Cross Sectional Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, M.; Roston, A.; Keith, L.; Patel, A. Effect of previous induced abortions on postabortion contraception selection. Contraception 2015, 91, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. Trends in contraceptive use and determinants of choice in China: 1980–2010. Contraception 2012, 85, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, A.R.A.; Lohr, P.A.; Aiken, C.E.; Forsyth, T.; Trussell, J. Contraceptive method preferences and provision after termination of pregnancy: A population-based analysis of women obtaining care with the British Pregnancy Advisory Service. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 124, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asubiojo, B.; Ng’wamkai, P.E.; Shayo, B.C.; Mwangi, R.; Mahande, M.J.; Msuya, S.E.; Maro, E. Predictors and Barriers to Post Abortion Family Planning Uptake in Hai District, Northern Tanzania: A Mixed Methods Study. East Afr. Health Res. J. 2021, 5, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.F.; Puri, M.; Rocca, C.H.; Blum, M.; Henderson, J.T. Service provider perspectives on post-abortion contraception in Nepal. Cult. Health Sex. 2016, 18, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odwe, G.; Wado, Y.D.; Obare, F.; Machiyama, K.; Cleland, J. Method-specific beliefs and subsequent contraceptive method choice: Results from a longitudinal study in urban and rural Kenya. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Richards, E.; Qian, X.; Zhang, W.; Hu, L.; Wu, S.; Tolhurst, R.; INPAC Consortium. Opportunities, challenges and systems requirements for developing post-abortion family planning services: Perceptions of service stakeholders in China. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Dusabe-Richards, E.; Wu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.-H.; Temmerman, M.; Tolhurst, R.; INPAC Group. A qualitative exploration of perceptions and experiences of contraceptive use, abortion and post-abortion family planning services (PAFP) in three provinces in China. BMC Womens Health 2017, 17, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wu, S.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Xu, J.; Temmerman, M.; Zhang, W.H.; INPAC Consortium. Post-abortion family planning counselling practice among abortion service providers in China: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 22, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, R. Factors associated with seeking post-abortion care among women in Guangzhou, China. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.P.; Zhu, W.L.; Li, S.M.; Teng, Y.C. Acceptance and Continuation of Contraceptive Methods Immediate Postabortion. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2017, 82, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.X.; Luo, Y.; Chen, M.Z.; Zhou, Y.H.; Meng, Y.T.; Wang, T.; Qin, S.; Xu, C. Associations among menopausal status, menopausal symptoms, and depressive symptoms in midlife women in Hunan Province, China. Climacteric 2020, 23, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers. 2018 World Health Organization and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260156/9780999203705-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Contraceptive Effectiveness in the United States. GUTTMACHER INSTITUTE. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/contraceptive-effectiveness-united-states (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Evans, W.D.; Ulasevich, A.; Hatheway, M.; Deperthes, B. Systematic Review of Peer-Reviewed Literature on Global Condom Promotion Programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Di, W.; Ding, Y.; Fan, G.S.; Gu, X.Y.; Hao, M.; He, J.; Hu, L.N.; Hua, K.Q.; Huang, W.; et al. Chinese expert consensus on the clinical use of female contraceptive methods. Chin. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 53, 433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Postabortion Contraception Service Standards. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Department of Maternal and Child Health. 2018. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fys/s7904/201808/c211b0059b1447119bdf4f0a5128de50.shtml (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Akazili, J.; Kanmiki, E.W.; Anaseba, D.; Govender, V.; Danhoundo, G.; Koduah, A. Challenges and facilitators to the provision of sexual, reproductive health and rights services in Ghana. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1846247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanaugh, M.L.; Jones, R.K.; Finer, L.B. How commonly do US abortion clinics offer contraceptive services? Contraception 2010, 82, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, G.; Tura, G.; Kahsay, G.; Haile, K.; Grum, T.; Araya, T. Family planning utilization and factors associated among women receiving abortion services in health facilities of central zone towns of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A cross sectional Study. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.F.; Wu, J.Q.; Li, Y.Y.; Yu, C.N.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.R.; Zhang, J.G.; Jin, M.H. Association between factors related to family planning/sexual and reproductive health and contraceptive use as well as consistent condom use among internal migrant population of reproductive ages in three cities in China, based on Heckprobit selection models. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gebremedhin, S.A.; Opoku, S.; Abaidoo, C.S.; Mkandawire, T.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H. Determinants of modern contraceptive use among married women of reproductive age: A cross-sectional study in rural Zambia. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e030980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, M.P.; Kabamalan, M.M.; Laguna, E. Traditional and Modern Contraceptive Method Use in the Philippines: Trends and Determinants 2003–2013. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2018, 49, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosavi, A.; Ma, Y.; Wong, H.; Singh, K. Knowledge and factors determining choice of contraception among Singaporean women. Singap. Med. J. 2016, 57, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, C.; Bohet, A.; Hassoun, D.; Ringa, V.; Bajos, N. IUD use in France: Women’s and physician’s perspectives. Contraception 2014, 89, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Wu, S.; Zhang, A.; Li, J.; Gu, X. Cognition and attitude of postpartum contraception among obstetricians in Tianjin area. Chin. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 49, 842–846. [Google Scholar]

- Behulu, G.K.; Fenta, E.A.; Aynalem, G.L. Repeat induced abortion and associated factors among reproductive age women who seek abortion services in Debre Berhan town health institutions, Central Ethiopia, 2019. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, L.; Stumbras, K.; Lewnard, I.; Haider, S. Contraceptive Provision after Medication and Surgical Abortion. Women’s Health Issues Off. Publ. Jacobs Inst. Women’s Health 2017, 27, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.K.; Ogilvie, G.; Norman, W.V.; Fitzsimmons, B.; Maher, C.; Renner, R. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Mobile Technology Intervention to Support Postabortion Care (The FACTS Study Phase II) After Surgical Abortion: User-Centered Design. JMIR Hum. Factors 2019, 6, e14558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Gold, J.; Ngo, T.D.; Sumpter, C.; Free, C. Mobile phone-based interventions for improving contraception use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd011159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, B.; Mitchell, J.W.; Braun, K.L. Effectiveness of mHealth Interventions for Improving Contraceptive Use in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2020, 8, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Gao, L.; Anguzu, R.; Zhao, J. Long-acting reversible contraceptive use in the post-abortion period among women seeking abortion in mainland China: Intentions and barriers. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culwell, K.R.; Vekemans, M.; de Silva, U.; Hurwitz, M.; Crane, B.B. Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: Contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2010, 110, S13–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond-Smith, N.; Phillips, B.; Percher, J.; Saxena, M.; Dwivedi, P.; Srivastava, A. An intervention to improve the quality of medication abortion knowledge among pharmacists in India. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019, 147, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, C.X.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Stephansson, O.; Kang, J.Z.; Chen, Q.F.; Cheng, L.N. Emergency contraceptive use among 5677 women seeking abortion in Shanghai, China. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 1612–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wado, Y.D.; Dijkerman, S.; Fetters, T.; Wondimu, D.; Desta, D. The effects of a community-based intervention on women’s knowledge and attitudes about safe abortion in intervention and comparison towns in Oromia, Ethiopia. Women Health 2018, 58, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Contraceptive Methods | χ² | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 768) | Reliable (n = 692) | Unreliable (n = 76) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.719 | 0.698 | |||

| 20–29 | 103 (13.4%) | 91 (88.3%) | 12 (11.7%) | ||

| 30–39 | 208 (40.5%) | 186 (89.4%) | 22 (10.6%) | ||

| 40–49 | 457 (59.5%) | 415 (90.8%) | 42 (9.2%) | ||

| Residence | 2.628 | 0.105 | |||

| Urban | 459 (59.8%) | 407 (88.7%) | 52 (11.3%) | ||

| Rural | 309 (40.2%) | 285 (92.2%) | 24 (7.8%) | ||

| Education level #1 | 15.364 | <0.001 * | |||

| Low | 332 (43.2%) | 302 (91.0%) | 30 (9.0%) | ||

| Middle | 296 (38.5%) | 276 (93.2%) | 20 (6.8%) | ||

| High | 140 (18.2%) | 114 (81.4%) | 26 (18.6%) | ||

| Occupation | 17.610 | 0.001 * | |||

| Unemployed | 113 (14.7%) | 98 (86.7%) | 15 (13.3%) | ||

| Famer or worker | 285 (37.1%) | 272 (95.4%) | 13 (4.6%) | ||

| Professional or Administrative staff | 134 (17.4%) | 112 (83.6%) | 22 (16.4%) | ||

| Staff Business or Service personnel | 200 (26.0%) | 177 (88.5%) | 23 (11.5%) | ||

| Others | 36 (4.7%) | 33 (91.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | ||

| Marital status #2 | 0.054 | 0.816 | |||

| Being single | 45 (5.9%) | 41 (91.9%) | 4 (8.9%) | ||

| Being married | 723 (94.1%) | 651 (90.0%) | 72 (10.0%) | ||

| Personal monthly income (RMB) #3 | 1.478 | 0.687 | |||

| None | 108 (14.1%) | 97 (89.8%) | 11 (10.2%) | ||

| <3000 | 368 (47.9%) | 336 (91.3%) | 32 (8.7%) | ||

| 3000–4999 | 230 (29.9%) | 205 (89.1%) | 25 (10.9%) | ||

| ≥5000 | 62 (8.1%) | 54 (87.1%) | 8 (12.9) | ||

| Family monthly income (RMB) #3 | 1.830 | 0.401 | |||

| <3000 | 151 (19.7%) | 132 (87.4%) | 19 (12.6%) | ||

| 3000–4999 | 205 (26.7%) | 188 (91.7%) | 17 (8.3%) | ||

| ≥5000 | 412 (53.6%) | 372 (90.3%) | 40 (9.7%) | ||

| Number of children | 1.464 | 0.481 | |||

| 0 | 13 (1.7%) | 13 (100%) | 0 | ||

| 1 | 403 (52.5%) | 362 (89.8%) | 41 (10.2%) | ||

| ≥2 | 352 (45.8%) | 317 (90.1%) | 35 (9.9%) | ||

| Variables | Contraceptive Methods | χ² | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 768) | Reliable (n = 692) | Unreliable (n = 76) | |||

| What contraceptive methods did the service providers tell you about? | 35.884 | <0.001 * | |||

| Unreliable methods | 24 (3.1%) | 13 (54.2%) | 11 (45.8%) | ||

| Reliable methods | 744 (96.9%) | 679 (91.3%) | 65 (8.7%) | ||

| How many contraceptive methods did the service provider introduce you to? | 2.251 | 0.324 | |||

| Recommend only one method | 302 (39.3%) | 271 (89.7%) | 31 (10.3%) | ||

| Recommend various methods | 445 (57.9%) | 404 (90.8%) | 41 (9.2%) | ||

| Others | 21 (2.7%) | 17 (81.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | ||

| Were you informed about the side effects of the contraceptive methods? | 1.685 | 0.194 | |||

| No | 122 (15.9%) | 106 (86.9%) | 16 (13.1%) | ||

| Yes | 646 (84.1%) | 586 (90.7%) | 60 (9.3%) | ||

| How many factors did you know were risk factors for having an induced abortion? | |||||

| Points | 5.646 | 0.227 | |||

| 0 #4 | 249 (32.4%) | 232 (93.2%) | 17 (6.8%) | ||

| 1 | 149 (19.4%) | 132 (88.6%) | 17 (11.4%) | ||

| 2 | 184 (24.0%) | 167 (90.8%) | 17 (9.2%) | ||

| 3 | 124 (16.1%) | 109 (87.9%) | 15 (12.1%) | ||

| 4 | 62 (8.1%) | 52 (83.9%) | 10 (16.1%) | ||

| 5 | 0 | ||||

| Induced abortion history | 0.614 | 0.685 | |||

| 1 | 411 (53.5%) | 372 (90.5%) | 39 (9.5%) | ||

| ≥2 | 357 (46.5%) | 320 (89.6%) | 37 (10.4) | ||

| What procedure did you undergo with your most recent induced abortion? | 9.990 | 0.019 * | |||

| Medical abortion | 105 (13.7%) | 101 (96.2%) | 4 (3.8%) | ||

| Painless surgical abortion | 402 (52.3%) | 354 (88.1%) | 48 (11.9%) | ||

| Non-painless surgical abortion | 177 (23.0%) | 165 (93.2%) | 12 (6.8%) | ||

| Medical combined with surgical abortion | 84 (10.9%) | 72 (85.7%) | 12 (14.3%) | ||

| Were you satisfied with your most recent abortion services? | 1.214 | 0.545 | |||

| Satisfied | 459 (59.8%) | 412 (89.8%) | 47 (10.2%) | ||

| Neutral | 274 (35.7%) | 250 (91.2%) | 24 (8.8%) | ||

| Dissatisfied | 35 (4.6%) | 30 (85.7%) | 5 (14.3%) | ||

| Did you receive one-on-one contraceptive counselling one month after your IA? | 5.089 | 0.024 * | |||

| No | 331 (43.1%) | 289 (87.3%) | 42 (12.7%) | ||

| Yes | 437 (56.9%) | 403 (92.2%) | 34 (7.8%) | ||

| Model a #5 | Model b #6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | p | ORs | 95% CIs | p | ORs | 95% CIs |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Unemployed | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Farmer or Worker | 0.004 * | 0.297 | 0.130–0.678 | 0.004 * | 0.297 | 0.130–0.678 |

| Professional or Administrative staff | 0.946 | 1.030 | 0.437–2.426 | 0.946 | 1.030 | 0.437–2.426 |

| Staff business or Service personnel | 0.679 | 0.854 | 0.404–1.805 | 0.679 | 0.854 | 0.404–1.805 |

| Others | 0.158 | 0.350 | 0.081–1.506 | 0.158 | 0.350 | 0.081–1.506 |

| Family monthly income (RMB) | ||||||

| <3000 | – | – | – | |||

| 3000–4999 | 0.042 * | 0.454 | 0.212–0.973 | |||

| ≥5000 | 0.026 * | 0.455 | 0.228–0.909 | |||

| Unreliable methods | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Reliable methods | <0.001 * | 0.109 | 0.044–0.274 | 0.000 * | 0.098 | 0.039–0.250 |

| Medical abortion | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Painless surgical abortion | 0.027 * | 3.353 | 1.151–9.769 | 0.024 * | 3.465 | 1.177–10.201 |

| Non-painless surgical abortion | 0.328 | 1.811 | 0.551–5.949 | 0.303 | 1.879 | 0.566–6.246 |

| Medical and surgical abortion | 0.080 | 2.987 | 0.879–10.145 | 0.058 | 3.290 | 0.961–11.261 |

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 0.009 * | 0.506 | 0.303–0.846 | 0.021 * | 0.543 | 0.323–0.914 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, T. Factors Associated with the Choice of Contraceptive Method following an Induced Abortion after Receiving PFPS Counseling among Women Aged 20–49 Years in Hunan Province, China. Healthcare 2023, 11, 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040535

Tong C, Luo Y, Li T. Factors Associated with the Choice of Contraceptive Method following an Induced Abortion after Receiving PFPS Counseling among Women Aged 20–49 Years in Hunan Province, China. Healthcare. 2023; 11(4):535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040535

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Chenxi, Yang Luo, and Ting Li. 2023. "Factors Associated with the Choice of Contraceptive Method following an Induced Abortion after Receiving PFPS Counseling among Women Aged 20–49 Years in Hunan Province, China" Healthcare 11, no. 4: 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040535

APA StyleTong, C., Luo, Y., & Li, T. (2023). Factors Associated with the Choice of Contraceptive Method following an Induced Abortion after Receiving PFPS Counseling among Women Aged 20–49 Years in Hunan Province, China. Healthcare, 11(4), 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040535