Choosing Alternative Career Pathways after Immigration: Aspects Internationally Educated Physicians Consider when Narrowing down Non-Physician Career Choices

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prior Research and Significance of the Study

1.2. Theoretical Underpinnings

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

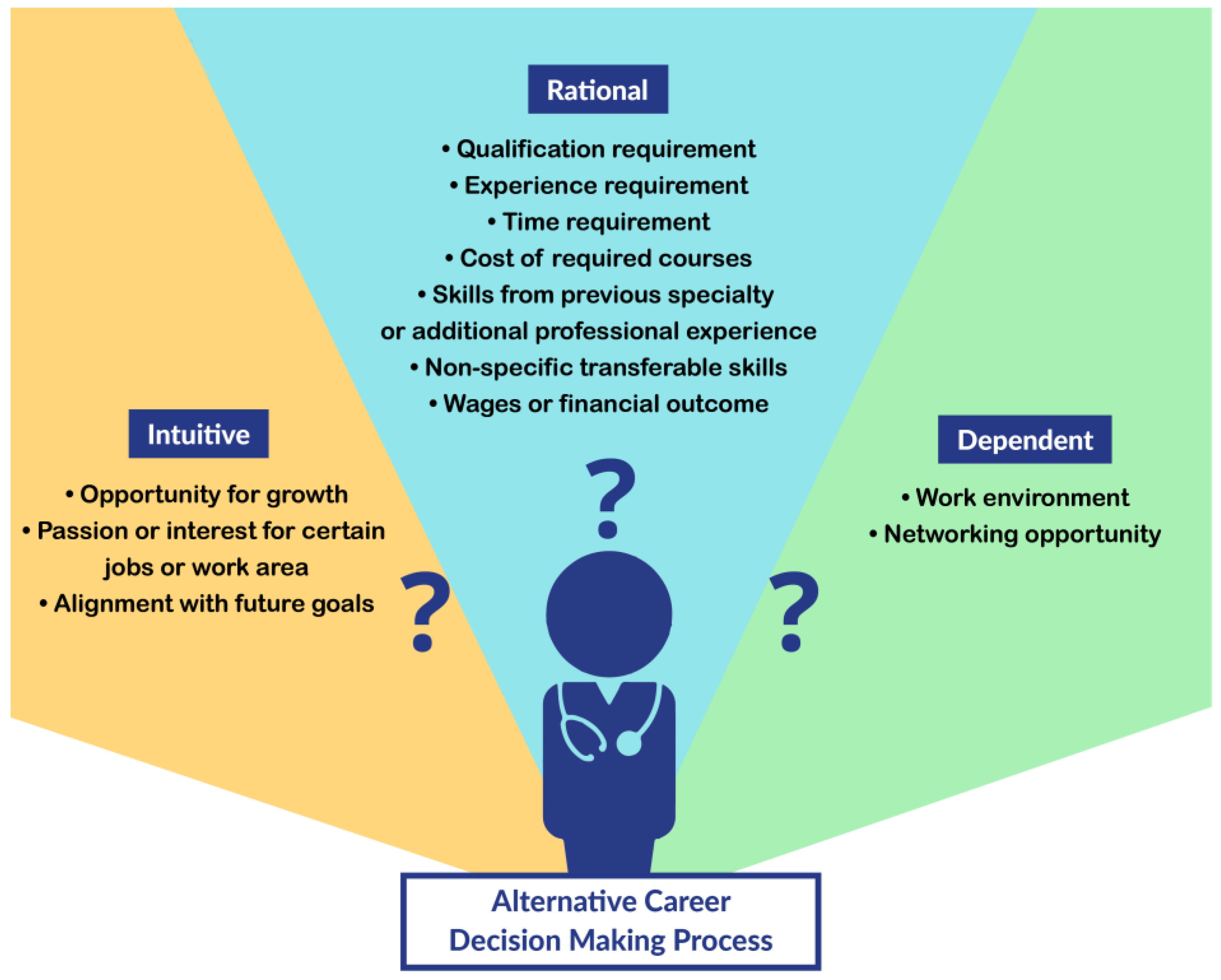

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Qualification and Experience Requirement

3.1.1. Sub-Theme: Qualification Requirement

“Yeah, sure. I’m actually very, um, enthusiastic about learning. So I am doing the clinical research certificate and I want to work and I don’t mind going back to school. I really want to be settled here, so I don’t mind going back to school.”(FGD4P5), FGD: Focus Group Discussion; P5: Participant No. 5.

“Uh, the thing that I am not open to is, as I mentioned before that I am at this point. Yeah. I’m not looking into going to school or going to upgrade myself. Uh, I think that it’s, it’s not in me. I lost that desire to do it. So I’m looking for something that can give me an opportunity to work now, instead of asking me to go back to school for one or two years, um, the otherwise I’m, I’m, uh, I can’t think of anything in particular. Uh, other than that.”(FGD4P2)

“So, so first off for the preparatory phase, I mean to say that certain courses require extensive qualification, uh, for example, um, like IELTS score GRE score experiences. Uh, so just to get into that course, I think that, yeah.”(FGD8P3).

3.1.2. Sub-Theme: Experience Requirement

“You actually have the skills, you have the certification, but they still want you to have had the Canadian experience, which still makes it tedious. Even with this medical office administration. The fact that I even went to school here, they still want me to have had two years experience.”(FGD3P3).

3.2. Theme 2: Personal Resource Requirement for Capacity Building

3.2.1. Sub-Theme: Time Requirement

“I will think about the time factor. So I, um, I can take any program or any, uh, on any course for a short time period. Um, maybe up to a year or two years maximum, uh, until I finished my studying and exams on so much, but more than that, I think it.”(FGD4P6).

3.2.2. Sub-Theme: Cost of Required Courses

“…you know, first and foremost, what I think is, uh, what is the cost of that course? Have to do, if I have to do a course and, uh, if I need, you know.”(FGD1P1)

“That’s not a problem for me, if it is needed, I’m also. Ready to invest for a course or whatever, but really the ever-changing Canadian and [muffled] landscape will be able to provide me with a job once I come out of it.”(FGD1P1)

3.3. Theme 3: Possibility of the Utilization of Transferable Skills

3.3.1. Sub-Theme: Skills from Previous Specialty or Additional Professional Experience

“Third thing, uh, trying to select something, that near to the medical field. Okay. So that it will not take lots of money from the person who is trying, for example, to study or to prepare to get in that field. And it will not be time-consuming the same time.”(FGD8P4)

“…since I have done the ARDMS (American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography). So, my first priority will be, when I think about the alternative career, it will be something related to this field. Like radiology or something, I know that’s really hard, but that will be my first priority and something related to patient.”(FGD2P6)

3.3.2. Sub-Theme: Non-Specific Transferable Skills

“So I have been working with people, managing people, a part of work that I have done before. Also, it has given me those skills to work with. So. People rather than just dealing with patients.”(FGD4P2)

3.4. Theme 4: Employment-Related Factors

3.4.1. Sub-Theme: Wages or Financial Outcome

“So financial outcome. Yes, remuneration. Actually, what you’re going to get, it should be sufficient enough to maintain dignity as well as your life.”(FGD1P3)

“Yeah, top three for me would be one would be income, um, location and three would be, um, how close is it to my actual work? So income, location, and the third one, the closeness to my role as a doctor.”(FGD4P3)

3.4.2. Sub-Theme: Flexibility in Working Hours

“That I might hold some kind of job, which is not too hectic to have a family and, um, to, to, to give time to the husband, to the kids. And you know, it’s not like, uh, a difficult, you know, like, well, flexible hours relaxing, but it’s still some, you know, some kind of income, basic income.(FGD2P5)

“…and I consider that is, working hours. Do I have to work on weekends? I have to do nights, or it’s just weekdays?”(FGD4P3)

3.4.3. Sub-Theme: Opportunity for Growth

“I needed to be in a, in a profession or something that I would like, can you going on and what I can grow and just continue and feel satisfied with it.”(FGD3P2).

“Yep. Um, so for the growth opportunity, I would say, you know, it might not be even again, a tangible thing that a lot of time actually come around with assistant development opportunities are provided or, you know, a mentorship is provided or coaching job coaching is private or something like that.”(FGD8P5).

“Initially they said that there was no opportunity for growth, but then as I was in the job, I saw a lot of opportunities as I went through it. Cause like, um, I had the opportunity to be part of research studies as well as our medical lab technician. So I was in contact with a lot of physicians, like in Alberta Children’s Hospital. And then at the same time now at the South health campus, we do a lot of research studies. And then there’s also this opportunity for more of the administrative part, like knowing the ins and outs of the laboratory, how it works.”(FGD5P5).

3.4.4. Sub-Theme: Job Demand and Availability

“Cause whenever I want to train on something, I want to train it good, like a hundred percent perfection, but the money that is required to do the training, if it has to come from me and I would want to have some kind of, um, reassurance that I’m going to get a job at the end.”(FGD2P5).

3.4.5. Sub-Theme: Networking Opportunity

“Um, yeah, many of the research groups that I’ve known I’ve worked with or know about they work in collaborations. So there’s a lot of opportunity to work with different stakeholders and different collaborators, even though they are different than universities that are collaborating together on a project.”(FGD6P1).

“So if you’re working in a team environment, you’re working with like, you know, 10 or 15 different peoples, you will get to know them. There is a networking opportunity, for sure.”(FGD8P2)

“Yeah. You can’t give it right. Like you can’t dictate it. Uh it’s because honestly, um, but from person to person, the networking ability differs.”(FGD8P1)

3.4.6. Sub-Theme: Work Environment

(From the Zoom chat feature) “Collaborative work environment, amount of stress and what do the employer (do) to manage staffs’ stress. One of the proxy could be what proportion of people are working in the specific workplace for what duration. How much they appreciate their staffs for the work they do. Paid vacation, sick leaves, family leaves, paid holidays, etc.”(FGD8P5).

3.5. Theme 5: Personal Level Factors

3.5.1. Sub-Theme: Passion or Interest for Certain Jobs or Work Area

“Like radiology, or something, I know that’s really hard, but that will be my first priority and something related to patient. Actually, since I, I worked solely through the clinical side. I don’t know. Is it possible or what, but if I got chance to work with the patient, uh, I will, I will definitely go through that, that being my first priority.”(FGD2P6)

3.5.2. Sub-Theme: Alignment with Future Goals

“…either that or that particular job is going to be a bridging job. Uh, or a position like a stepping stone, uh, for me to, uh, work for a little bit and then move on to something that is going to be my destination.”(FGD4P4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Expositions

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sumalinog, R.; Zacharias, A.; Rana, A. Backgrounder: International Medical Graduates (IMGs) and the Canadian Health Care System. Can. Fed. Med. Stud. 2015, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Motala, M.I.; Van Wyk, J.M. Experiences of Foreign Medical Graduates (FMGs), International Medical Graduates (IMGs) and Overseas Trained Graduates (OTGs) on Entering Developing or Middle-Income Countries like South Africa: A Scoping Review. Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Force Ontario Registration Requirements. Available online: http://www.healthforceontario.ca/en/Home/Health_Providers/Physicians/Registration_Requirements (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Chowdhury, N.; Ekpekurede, M.; Lake, D.; Chowdhury, T.T. The Alternative Career Pathways for International Medical Graduates in Health and Wellness Sector. In International Medical Graduates in the United States; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 293–325. [Google Scholar]

- Lim Consulting Associates Foreign Qualifications Recognition and Alternative Careers. The Best Practices and Thematic Task Team of the Foreign Qualifications Recognition Working Group. Available online: https://novascotia.ca/lae/RplLabourMobility/documents/AlternativeCareersResearchReport.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Independent Review of Access to Postgraduate Programs by International Medical Graduates in Ontario; Volume I: Findings and Recommendations. Available online: https://cou.ca/reports/independent-review-of-access-to-postgraduate-programs-by-international-medical-graduates-in-ontario-volume-i-findings-and-recommendations (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- The Canadian Resident Matching Service. Available online: https://practiceinbc.ca/for-gps/canadian-medical-graduates/canadian-resident-matching-service (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Ekpekurede, M.; Lake, D.; Lasker, M.; O’Brien, M.; Goopy, S. Alternative Career Pathways for International Medical Graduates towards Job Market Integration: A Literature Review. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2021, 12, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeault, I.L.; Neiterman, E.; Lebrun, J.; Viers, K.; Winkup, J. Brain Gain, Drain & Waste: The Experiences of Internationally Educated Health Professionals in Canada; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sood, A. A Study of Immigrant International Medical Graduates’ Re-Licensing in Ontario: Their Experiences, Reflections, and Recommendations. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Das, R.L.V.; Lapa, T.; Marosan, P.; Pawliuk, R.; Chable, H.D.; Lake, D.; Lofters, A. Career Development of International Medical Graduates in Canada: Status of the Unmatched. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Lake, D.; Chowdhury, M.Z.I. Labor Market Integration of High-Skilled Immigrants in Canada: Employment Patterns of International Medical Graduates in Alternative Jobs. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beran, T.N.; Violato, E.; Faremo, S.; Violato, C.; Watt, D.; Lake, D. Ego Identity Development in Physicians: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Using a Mixed Method Approach. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberta International Medical Graduates Association (AIMGA). Available online: https://www.newcomernavigation.ca/en/news/featured-organization-the-alberta-international-medical-graduate-association-aimga.aspx (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Blain, M.J.; Fortin, S.; Alvarez, F. Professional Journeys of International Medical Graduates in Quebec: Recognition, Uphill Battles, or Career Change. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2017, 18, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, S. Career Options and Professional Integration of Internationally Trained Physicians in Canada. Can. Health Policy 2020, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ariss, A.; Koall, I.; Özbilgin, M.; Suutari, V. Careers of Skilled Migrants: Towards a Theoretical and Methodological Expansion. J. Manag. Dev. 2012, 31, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, K.S. Underemployment and Labor Market Incorporation of Highly Skilled Immigrants With Professional Skills. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Employment Gaps and Underemployment for Racialized Groups and Immigrants in Canada: Current Findings and Future Directions. Available online: https://fsc-ccf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/EmploymentGaps-Immigrants-PPF-JAN2020-EN.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Cheng, L.; Spaling, M.; Song, X. Barriers and Facilitators to Professional Licensure and Certification Testing in Canada: Perspectives of Internationally Educated Professionals. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2013, 14, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.W.L.; Shankar, J.; Khalema, E. Unspoken Skills and Tactics: Essentials for Immigrant Professionals in Integration to Workplace Culture. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2017, 18, 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, S.; Galabuzi, G.-E. Canada’s Colour Coded Labour Market. Can. Cent. Policy Altern. 2011, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, K.; Chua, C. Linguistic Outcomes of Language Accountability and Points-Based System for Multilingual Skilled Immigrants in Canada: A Critical Language-in-Immigration Policy Analysis. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, J.G.; Curtis, J.; Elrick, J. Immigrant Skill Utilization: Trends and Policy Issues. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2014, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siar, S.V. From Highly Skilled to Low Skilled: Revisiting the Deskilling of Migrant Labor; Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS): Quezon, Philippines, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, H.J. Immigrant Professionals and Alternative Routes to Licensing: Policy Implications for Regulators and Government. Can. Public Policy 2015, 41, S14–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiterman, E.; Bourgeault, I.L.; Covell, C.L. What Do We Know and Not Know about the Professional Integration of International Medical Graduates (IMGs) in Canada? Healthc. Policy 2017, 12, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Medical Graduates-Current Issues. Available online: https://www.acponline.org/international-medical-graduates-strengths-and-weaknesses-of-international-medical-graduates-in-us (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Shuval, J.T. The Reconstruction of Professional Identity Among Immigrant Physicians in Three Societies. J. Immigr. Health 2000, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; ISBN 0226041220. [Google Scholar]

- Buzdugan, R.; Halli, S.S. Labor Market Experiences of Canadian Immigrants with Focus on Foreign Education and Experience. Int. Migr. Rev. 2009, 43, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internationally Educated Health Professionals in Canada: Navigating Three Policy Subsystems along the Pathway to Practice. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306026312_Internationally_Educated_Health_Professionals_in_Canada_Navigating_Three_Policy_Subsystems_Along_the_Pathway_to_Practice (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Creese, G.; Wiebe, B. ‘Survival Employment: Gender and Deskilling among African Immigrants in Canada. Int. Migr. 2012, 50, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occupational Dimensions of Immigrant Credential Assessment: Trends in Professional, Managerial, and Other Occupations. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228599355_Occupational_dimensions_of_immigrant_credential_assessment_Trends_in_professional_managerial_and_other_occupations_1970-1996 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Available online: https://www.gwptoolbox.org/resource/mapping-margins-intersectionality-identity-politics-and-violence-against-women-color (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Hassan, F. Intersectionality and the Role of Service Providers: A Step Towards Improving the Employment Outcomes of Immigrant Women. Ph.D. Thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-8039-3186-7. [Google Scholar]

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Lake, D. Alternative Careers toward Job Market Integration: Barriers Faced by International Medical Graduates in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.S. Purposive Sampling. Encycl. Qual. Life Well-Being Res. 2014, 5243–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who Is Succeeding in the Canadian Labour Market?: Predictors of Career Success for Skilled Immigrants. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED602857.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Racism, Discrimination and Migrant Workers in Canada: Evidence from the Literature. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/reports-statistics/research/racism-discrimination-migrant-workers-canada-evidence-literature.html (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Awareness of Ageism While Researching Multiple Minority Discrimination: A Discourse and Grounded Theory Analysis Revisiting Own Qualitative Research. Available online: https://newsletter.x-mol.com/paper/1602761267624923136 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Determinants and Effects of Post-Migration Education Among New Immigrants in Canada. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ubc/clssrn/clsrn_admin-2009-20.html (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Osaze, E.D. The Non-Recognition or Devaluation of Foreign Professional Immigrants Credentials in Canada: The Impact on the Receiving Country (Canada) and the Immigrants; York Space: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, J. Employment Match Rates in the Regulated Professions: Trends and Policy Implications. Can. Public Policy 2015, 41, s28–s47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C. The Bridging Education and Licensure of International Medical Doctors in Ontario: A Call for Commitment, Consistency, and Transparency. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.; Novicevic, M.M.; Zikic, J. Career Success of Immigrant Professionals: Stock and Flow of Their Career Capital. Int. J. Manpow. 2009, 30, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, L.; Chen, C.P. Career Development of Foreign Trained Immigrants from Regulated Professions. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2012, 131, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.D. Choice and Change: Convergence from the Decision-Making Perspective. In Convergence in Career Development Theories: Implications for Science and Practice; Savickas, M.L., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Davies-Black: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S.D. Toward an Expanded Definition of Adaptive Decision Making. Career Dev. Q. 1997, 45, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, P.J.; Blustein, D.L. Reason, Intuition, and Social Justice: Elaborating on Parsons’s Career Decision-Making Model. J. Couns. Dev. 2002, 80, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Greenhaus, J.H. The Relation between Career Decision-Making Strategies and Person-Job Fit: A Study of Job Changers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oringderff, J. “My Way”: Piloting an Online Focus Group. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2004, 3, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Ekpekurede, M.; Lake, D.; Lasker, M.A.A.; O’Brien, M.; Goopy, S. Professional Integration of Immigrant Medical Professionals through Alternative Career Pathways: An Internet Scan to Synthesize the Current Landscape. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Lake, D. Lost in transition: The need for a strategic approach to facilitate job market integration of internationally educated physicians through alternative careers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vapor, V.R.; Xu, Y. Double Whammy for a New Breed of Foreign-Educated Nurses: Lived Experiences of Filipino Physician-Turned Nurses in the United States. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2011, 25, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Traits | % | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 29 or younger | 9.5 | 4 |

| 30–39 | 40.5 | 17 |

| 40–49 | 33.3 | 14 |

| 50 or over | 16.8 | 7 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 26.2 | 11 |

| Female | 73.9 | 31 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Armenia | 2.4 | 1 |

| Bangladesh | 12.0 | 5 |

| Canada | 4.8 | 2 |

| China | 2.4 | 1 |

| Colombia | 2.4 | 1 |

| Egypt | 2.4 | 1 |

| India | 14.3 | 6 |

| Iraq | 2.4 | 1 |

| Mexico | 2.4 | 1 |

| Nepal | 2.4 | 1 |

| Nigeria | 14.5 | 6 |

| Pakistan | 21.4 | 9 |

| Philippines | 7.1 | 3 |

| Somalia | 2.4 | 1 |

| Spain | 2.4 | 1 |

| Sudan | 2.4 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 2.4 | 1 |

| Province currently living in | ||

| Alberta | 71.4 | 30 |

| British Columbia | 7.1 | 3 |

| Manitoba | 4.8 | 2 |

| Ontario | 14.3 | 6 |

| Quebec | 2.4 | 1 |

| Immigration status | ||

| Citizen | 47.7 | 20 |

| Permanent resident | 47.7 | 20 |

| Refugee | 0.0 | 0 |

| Temporary migrant (on a student visa, work visa, or visitor visa) | 4.8 | 2 |

| Specialty before coming to Canada | ||

| Emergency medicine specialist | 4.8 | 2 |

| Family/general physician | 38.1 | 16 |

| Nephrologist | 2.4 | 1 |

| Neurological surgeon | 2.4 | 1 |

| Obstetrician | 7.1 | 3 |

| Occupational medicine specialist | 2.4 | 1 |

| Ophthalmologist | 4.8 | 2 |

| Paediatrician | 4.8 | 2 |

| Radiologist | 4.8 | 2 |

| Surgeon | 2.4 | 1 |

| Other | 26.2 | 11 |

| Others included: MPH, MD, FCPS, FRCS, or other post-graduate training in various specialty | ||

| Current work position | ||

| Employed (full-time) | 33.3 | 14 |

| Employed (part-time) | 26.2 | 11 |

| Unemployed; seeking work | 33.3 | 14 |

| Unemployed; not seeking work | 7.1 | 3 |

| Current area of work (among employed 25 participants) | ||

| Health-related (regulated alternative career, i.e., requires licensure procedure, e.g., nursing, pharmacy technician, EMS tech, sonography, or laboratory technician) | 20.0 | 5 |

| Health-related (non-regulated alternative career, i.e., does not require licensure, e.g., health educator, health administrative officer, researcher, health policy analyst) | 60.0 | 15 |

| Non-health-related professional job (non-medical career build-up, e.g., engineering, business, or life sciences) | 8.0 | 2 |

| Non-health-related non-professional job (i.e., survival job, e.g., Uber/taxi driving, store jobs, or business owner) | 12.0 | 3 |

| Years spent preparing for alternative careers | ||

| Less than a year | 35.7 | 15 |

| 1–3 years | 47.6 | 20 |

| 4–5 years | 9.5 | 4 |

| More than 5 years | 7.1 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chowdhury, N.; Lake, D.; Turin, T.C. Choosing Alternative Career Pathways after Immigration: Aspects Internationally Educated Physicians Consider when Narrowing down Non-Physician Career Choices. Healthcare 2023, 11, 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050657

Chowdhury N, Lake D, Turin TC. Choosing Alternative Career Pathways after Immigration: Aspects Internationally Educated Physicians Consider when Narrowing down Non-Physician Career Choices. Healthcare. 2023; 11(5):657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050657

Chicago/Turabian StyleChowdhury, Nashit, Deidre Lake, and Tanvir C. Turin. 2023. "Choosing Alternative Career Pathways after Immigration: Aspects Internationally Educated Physicians Consider when Narrowing down Non-Physician Career Choices" Healthcare 11, no. 5: 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050657

APA StyleChowdhury, N., Lake, D., & Turin, T. C. (2023). Choosing Alternative Career Pathways after Immigration: Aspects Internationally Educated Physicians Consider when Narrowing down Non-Physician Career Choices. Healthcare, 11(5), 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050657