Safety Survey on Lone Working Magnetic Resonance Imaging Technologists in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Online Study

2.3. Questionnaire Survey

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stafford, R.J. The Physics of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Safety. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. 2020, 28, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katti, G.; Ara, S.A.; Shireen, A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–A review. Int. J. Dent. Clin. 2011, 3, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Shellock, F.G. Magnetic resonance safety update 2002: Implants and devices. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2002, 16, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, T.; Chavhan, G.B.; Sze, R.W.; Swenson, D.; Holowka, S.; Fricke, S.; Davidson, S.; Iyer, R.S. Practical considerations for establishing and maintaining a magnetic resonance imaging safety program in a pediatric practice. Pediatr. Radiol. 2019, 49, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downie, A.; Hancock, M.; Jenkins, H.; Buchbinder, R.; Harris, I.; Underwood, M.; Goergen, S.; Maher, C.G. How common is imaging for low back pain in primary and emergency care? Systematic review and meta-analysis of over 4 million imaging requests across 21 years. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shellock, F.G.; Crues, J.V. Corneal temperature changes induced by high-field-strength MR imaging with a head coil. Radiology 1988, 167, 809–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi-Sekino, S.; Sekino, M.; Ueno, S. Biological Effects of Electromagnetic Fields and Recently Updated Safety Guidelines for Strong Static Magnetic Fields. Magn. Reson. Med Sci. 2011, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartwig, V.; Giovannetti, G.; Vanello, N.; Lombardi, M.; Landini, L.; Simi, S. Biological Effects and Safety in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 1778–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, L.L.; Grant, A.K.; Mortele, K.J.; Kung, J.W.; Smith, M.P. A Practical Guide to MR Imaging Safety: What Radiologists Need to Know. Radiographics 2015, 35, 1722–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Radiology. ACR Manual on MR Safety. 2020. Available online: https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Radiology-Safety/MR-Safety (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Kanal, E.; Froelich, J.; Barkovich, A.J.; Borgstede, J.; Bradley, W., Jr.; Gimbel, J.R.; Gosbee, J.; Greenberg, T.; Jackson, E.; Larson, P.; et al. Standardized MR terminology and reporting of implants and devices as recommended by the American College of Radiology Subcommittee on MR Safety. Radiology 2015, 274, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewland, T.A.; Hancock, L.N.; Sargeant, S.; Bailey, R.K.M.-A.; Sarginson, R.A.; Ng, C.K.C. Study of lone working magnetic resonance technologists in Western Australia. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2013, 26, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyke, L.M. Working Alone in MRI?: Policies to Reduce Risk when Working Alone in the MRI Environment. Can. J. Med Radiat. Technol. 2007, 38, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJOEM, T. Canadian Center for Occupational Health and Safety. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 1, 204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Lai, S.; Lima, J.A. MRI gadolinium dosing on basis of blood volume. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, M.J.; Shubayr, N.; Alomair, O.I.; Alkhorayef, M.; Alashban, Y.; Alahmari, D.M.; Alghamdi, S.A. Safety related for lone working magnetic resonance technologists in Southern Saudi Arabia. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleem, S.A.; Alsabaani, A.; Alamri, R.S.; Hadi, R.A.; Alkhayri, M.H.; Badawi, K.K.; Badawi, A.G.; AlShehri, A.A.; Al-Bishi, A.M. Violence towards healthcare workers: A study conducted in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2018, 25, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Stogiannos, N.; Westbrook, C. Investigating MRI safety practices in Greece. A national survey. Hell. J. Radiol. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N.M.; Hoff, M.N.; Kanal, K.M. Avoiding MRI-related accidents: A practical approach to implementing MR safety. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2018, 15, 1738–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.A. Assessment of MRI Safety Practices in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2023, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.; Rana, S.; Parvin, T.; Muraduzzaman, S.M.; Ahmed, M. Evaluation of Knowledge, Awareness, And Attitude Of Mri Technologists Towards Mri Safety in Dhaka City of Bangladesh. Hospital 2020, 20, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Fu, J.; Chang, Y.; Wang, L. Epidemiological study on risk factors for anxiety disorder among Chinese doctors. J. Occup. Health 2012, 54, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohidnia, M.-R.; Rostami, R.; Ghomshei, S.M.; Moradi, S.; Azizi, S.A. Incidence rate of physical and verbal violence inflicted by patient and their companions on the radiology department staff of educational hospitals of medical university, Kermanshah, 2017. La Radiol. medica 2019, 124, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersson, A.D.; Gorleku, P.N. A national survey of MRI safety practices in Ghana. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Criteria | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Experience | Less than 6 months | 49 (22) |

| From 6 months to less than a year | 31(13.9) | |

| 1–3 years | 43 (19.3) | |

| 4–10 years | 56 (25.1) | |

| More than 10 years | 44 (19.7) | |

| Participants from each region | Albaha | 8 (5) |

| Asir | 13 (7) | |

| Riyadh | 42 (24) | |

| Makkah | 31 (18) | |

| Eastern Province | 22 (13) | |

| Northern Borders | 7 (4) | |

| Jezan | 13 (7) | |

| Tabuk | 6 (3) | |

| Qasim | 14 (9) | |

| Madinah | 11 (6) | |

| Jawf | 2 (1) | |

| Najran | 2 (1) | |

| Hail | 3 (2) | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 157 (90.23) |

| Non-Saudi | 17 (9.77) | |

| Gender | Male | 109 (62.6) |

| Female | 65 (37.4) | |

| Age | Less than 30 years. | 53 (30.5) |

| Between 30–40 years. | 91 (52.3) | |

| More than 40 years. | 30 (17.2) | |

| Average number of patients/machine/days | Less than 10 (<10) patients | 31 (17.8) |

| 10–16 patients | 74 (42.5) | |

| More than 16 (>16) patients | 69 (39.7) | |

| Type of health care setting | Public hospital | 145 (83) |

| Private center | 29 (17) | |

| Job type | Full-time | 165 (95) |

| Part-time | 9 (5) | |

| Qualifications | Diploma | 29 (13) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 104 (46.6) | |

| Master’s degree | 35 (15.7) | |

| PhD | 5 (2.2) | |

| Saudi fellowship for radiology technologists | 1 (0.4) |

| Items | Criteria | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The presence of an MRSO in the department | Available | 55 (31.6) |

| Not available | 119 (68.4) | |

| The availability of policies for the reporting of safety accidents that occur in the MRI department | Available | 139 (79.9) |

| Not available | 35 (20.1) | |

| Have you received training in the following areas: [MRI safety]? | Yes | 109 (63) |

| No | 65 (37) | |

| Have you received training in the following areas: [first aid]? | Yes | 145 (83) |

| No | 29 (17) | |

| The extent of self-confidence and preferences when you are working as the only MRI technologist in the presence of another medical staff member (such as nurses) | Not confident at all | 5 (3) |

| Not very confident | 7 (4) | |

| Moderately confident | 33 (19) | |

| Highly confident | 61 (35) | |

| Completely confident | 68 (39) | |

| According to the American College of Radiology (ACR), working alone in the MRI unit is optional, depending on the person’s desire and ability to work alone | True | 38 (22) |

| False | 69 (40) | |

| I don’t know | 67 (38) | |

| Preference to work with another qualified MRI technologist | Very undesirable | 1 (1) |

| Undesirable | 10 (6) | |

| Neutral | 24 (14) | |

| Desirable | 58 (33) | |

| Very desirable | 81 (47) |

| Q. According to the American College of Radiology (ACR), Working Alone in an MRI Unit is Optional, Depending on the Person’s Desire and Ability to Work Alone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Criteria | Number of Incorrect Answers (%) | Number of Correct Answers (%) | p-Value |

| Gender | Male | 24 (63.2) | 85 (62.5) | 0.979 a |

| Female | 14 (36.8) | 51 (37.5) | ||

| Diploma | 18 (13) | 11 (29) | ||

| Qualification | Bachelor | 80 (59) | 24 (63) | b |

| Master | 32 (24) | 3 (8) | 0.255 c | |

| 0.003 d | ||||

| Ph.D. | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Fellowship | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| MRI experience | 6 months to <1 year | 23 (17) | 8 (21) | |

| 1–3 years | 38 (28) | 5 (13) | 0.015 e | |

| 4–10 years | 40 (29) | 16 (42) | 0.050 f | |

| >10 years | 35 (26) | 9 (24) | 0.527 g | |

| Based on Four-Point Likert Scale Questions a | Public (Mean Rank) | Private (Mean Rank) | H b | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

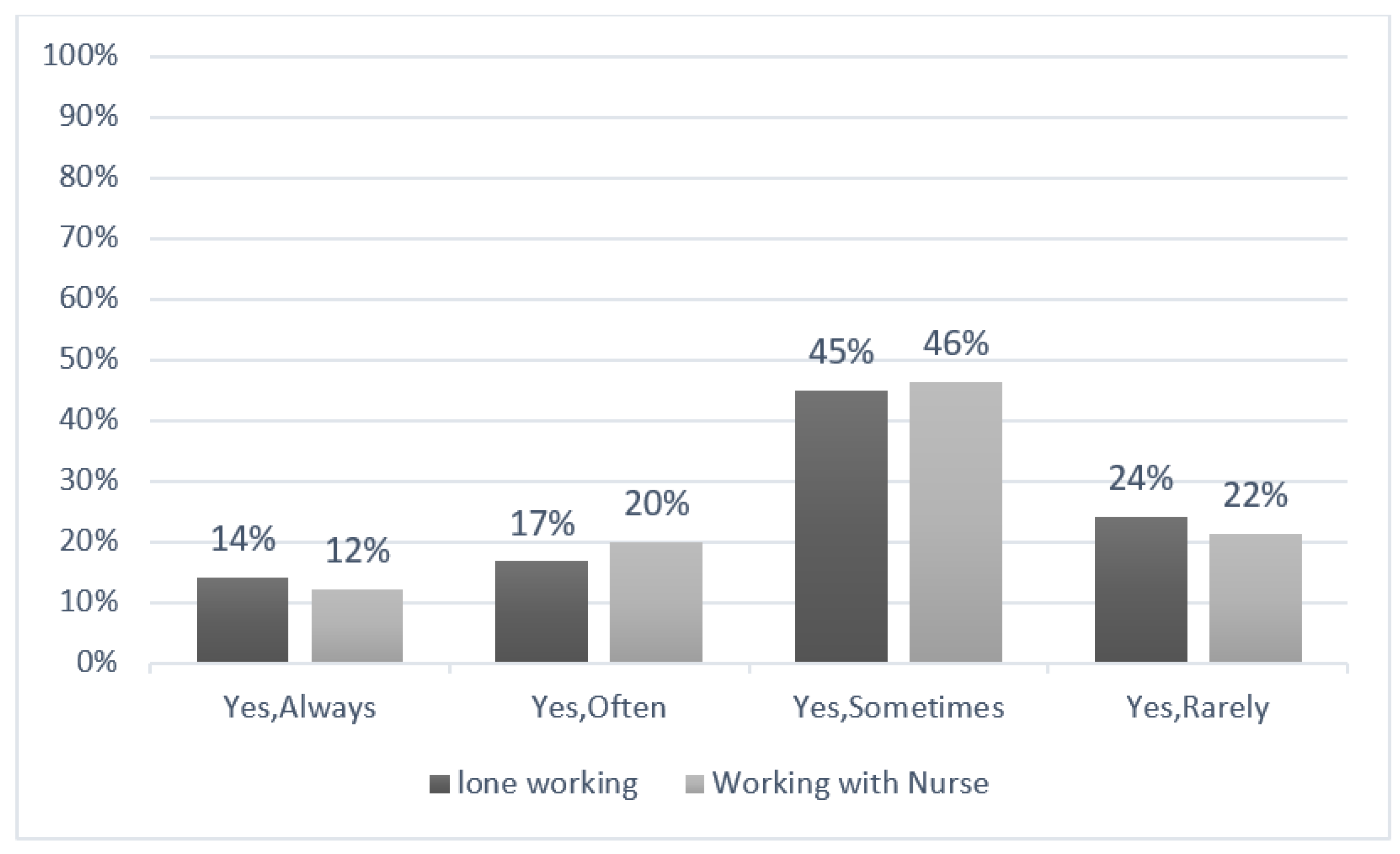

| Rate of lone working (n = 149) | 82.52 | 112.38 | 9.163 | 0.002 |

| Rate of working as the only MR technologist with the presence of another medical staff member (such as nurses) (n = 155) | 87.06 | 89.72 | 0.074 | 0.785 |

| Comparison between Different Concerns and Accidents/Mistakes experienced by MRI Technologists while They Are Working as: (A) A Lone MRI Technologist (n = 149) (B) An MRI Technologist in the Presence of Another Medical Staff Member (such as Nurses) (n = 155) | H a | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns b |

| A | 2.387 | 0.496 |

| B | 4.51 | 0.211 | ||

| A | 3.363 | 0.339 | |

| B | 1.606 | 0.658 | ||

| A | 4.737 | 0.192 | |

| B | 6.651 | 0.084 | ||

| A | 1.711 | 0.635 | |

| B | 9.165 | 0.027 | ||

| A | 5.63 | 0.131 | |

| B | 0.908 | 0.823 | ||

| A | 3.018 | 0.389 | |

| B | 3.553 | 0.314 | ||

| Accidents/Mistakes c |

| A | 2.40 | 0.49 |

| B | 3.53 | 0.32 | ||

| A | 2.98 | 0.39 | |

| B | 1.51 | 0.68 | ||

| A | 9.15 | 0.03 | |

| B | 2.98 | 0.39 | ||

| A | 6.17 | 0.10 | |

| B | 18.70 | 0.00 | ||

| Descriptive Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | n | Correlation | |

| The presence of an MRI safety officer (MRSO) in the department | 1.68 | 0.466 | 174 | 0.310 |

| The availability of policies for reporting safety accidents that occur in the MRI unit | 1.2 | 0.402 | 174 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alghamdi, S.A.; Alshamrani, S.A.; Alomair, O.I.; Alashban, Y.I.; Abujamea, A.H.; Mattar, E.H.; Almalki, M.; Alkhorayef, M. Safety Survey on Lone Working Magnetic Resonance Imaging Technologists in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050721

Alghamdi SA, Alshamrani SA, Alomair OI, Alashban YI, Abujamea AH, Mattar EH, Almalki M, Alkhorayef M. Safety Survey on Lone Working Magnetic Resonance Imaging Technologists in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2023; 11(5):721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050721

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlghamdi, Sami A., Saad A. Alshamrani, Othman I. Alomair, Yazeed I. Alashban, Abdullah H. Abujamea, Essam H. Mattar, Mohammed Almalki, and Mohammed Alkhorayef. 2023. "Safety Survey on Lone Working Magnetic Resonance Imaging Technologists in Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 11, no. 5: 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050721