Reliability and Validity of the Defeat Scale among Internal Migrant Workers in China: Decadence and Low Sense of Achievement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample Size

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Defeat Scale

2.4.2. Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

2.4.3. Revised Version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

2.5. Statistical Methods

2.5.1. Content Validity

2.5.2. Structural Validity Test by Factor Analysis

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett’s Test

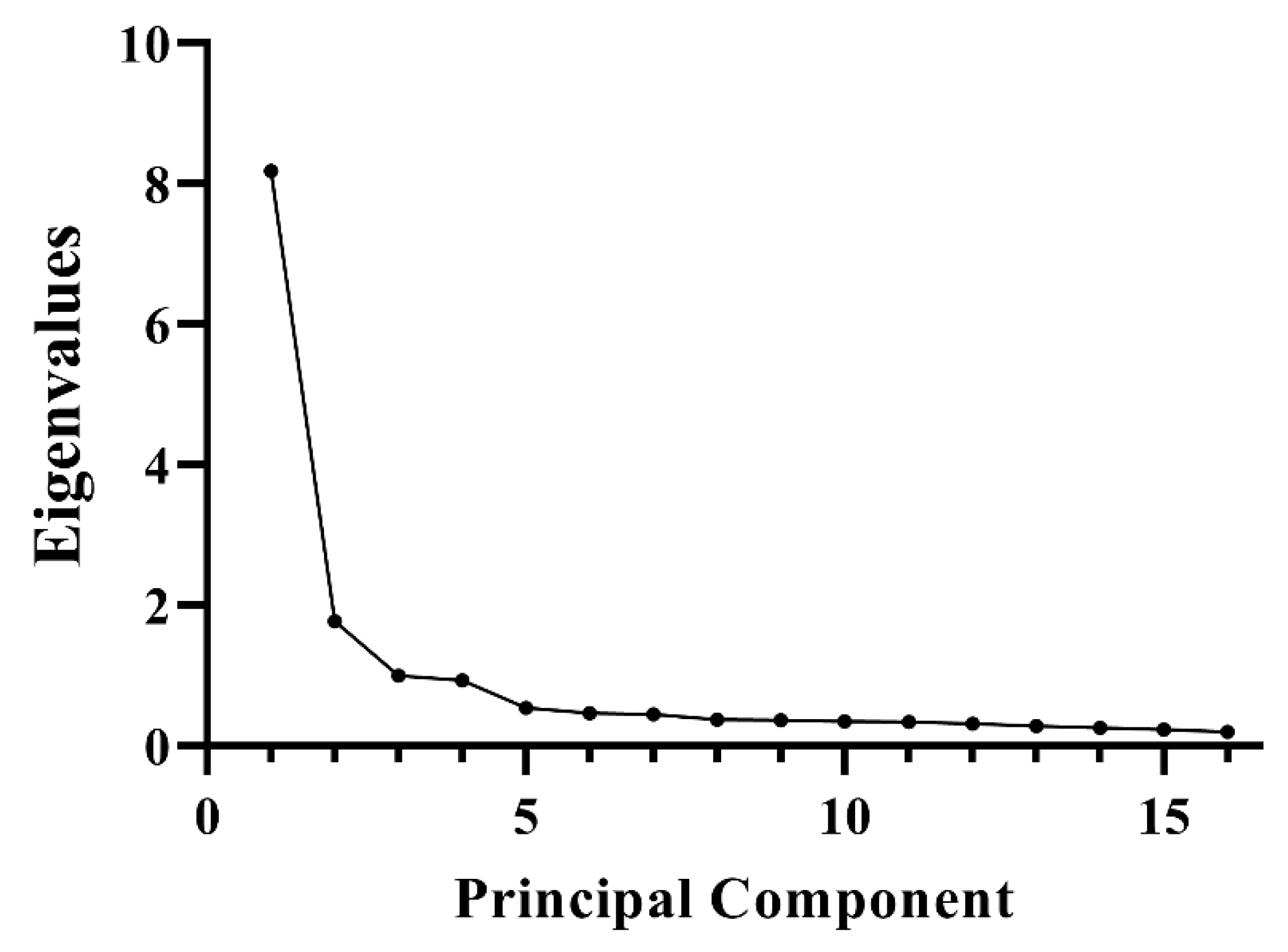

Screen Test

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

2.5.3. Reliability Test

2.5.4. Validity Test

Convergent Validity

Discriminant Validity

2.5.5. Logistic Regression

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

3.2. Content Validity

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.5. Reliability

3.6. Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity

3.7. Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- State Council. Several Opinions of the State Council on Solving the Problem of Migrant Workers. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2008-03/28/content_6668.htm (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- State Council. Regulations to Protect the Payment of Wages to Migrant Workers. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-01/07/content_5467278.htm (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistics China. 2020 Migrant Worker Monitoring Survey Report. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202104/t20210430_1816933.html (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Data for 2020. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0301&sj=2020 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Gilbert, P.; Allan, S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: An exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forkmann, T.; Stenzel, J.-S.; Rath, D.; Glaesmer, H.; Teismann, T. „Vom Leben geschlagen “–Validierung der deutschen Version der Defeat Scale (DS-d). PPmP-Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2018, 68, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilbert, P. Varieties of submissive behavior as forms of social defense: Their evolution and role in depression. In Subordination and Defeat: An Evolutionary Approach to Mood Disorders and Their Therapy; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Li, S.-m.; Hao, P. ‘Anyway, you are an outsider’: Temporary migrants in urban China. Urban Studies 2018, 55, 3185–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, G. Together but unequal: Citizenship rights for migrants and locals in urban China. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 50, 781–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. Quality matters: Housing and the mental health of rural migrants in urban China. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 1422–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Hong, Y.; Fang, X.; Qin, X.; Stanton, B. Discrimination, perceived social inequity, and mental health among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, D. Policing and racialization of rural migrant workers in Chinese cities. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2010, 33, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Stuck in the suburbs? Socio-spatial exclusion of migrants in Shanghai. Cities 2017, 60, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, G. The Economics of Discrimination; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, P.T.T.; Peeren, E. Exploiting the distance between conflicting norms: Female rural-to-urban migrant workers in Shanghai negotiating stigma around singlehood and marriage. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2019, 22, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, P.; Caine, E.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Ma, X. Depression and associated factors in internal migrant workers in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 134, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shao, C.; Meng, X.; Cui, S.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Income-related health inequality of migrant workers in China and its decomposition: An analysis based on the 2012 China Labor-force Dynamics Survey data. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2016, 79, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, B.L.; Liu, T.B.; Chan, S.S.M.; Jin, D.; Hu, C.Y.; Dai, J.; Chiu, H.F.K. Common mental health problems in rural-to-urban migrant workers in Shenzhen, China: Prevalence and risk factors. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiq, S.; Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R. Effect of internal migration on the environment in China. Energy Econ. 2017, 64, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W. New Trends in Internal Migration in China:Profiles of the New-generation Migrants. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Yang, Y.; Chi, G. Does the mental health of migrant workers suffer from long commute time? Evidence from China. J. Transp. Health 2020, 19, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Statistical Yearbook. National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2019; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Smyth, R. Happiness and job satisfaction in urban China: A comparative study of two generations of migrants and urban locals. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2160–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slade, K.; Edelmann, R.; Worrall, M.; Bray, D. Applying the C ry of P ain Model as a predictor of deliberate self-harm in an early-stage adult male prison population. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2014, 19, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akın, A.; Uysal, R.; Çitemel, N.; Akın, Ü. The Validity and Reliability of Turkish Version of the Defeat Scale. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2013, 5, 660–666. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, H.; Kang, H.H.; Moon, H.S.; Lee, S.H. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2020, 36, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bobov, G.; Capik, C. The Reliability and Validity of the Religious Health Fatalism Scale in Turkish Language. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 1080–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.B.; Aderka, I.M.; Lee, J.; Beard, C.; Bj?Rgvinsson, T.S. A Comparison of Three Brief Depression Measures in an Acute Psychiatric Population: CES-D-10, QIDS-SR, and DASS-21-DEP. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2015, 37, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, S.; Gong, R.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Y. Reliability and validity of defeat scale on anxiety and depression in medical students. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 39, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Xu, C.; Dong, J.; Yu, X.; Cai, Y.; Yuan, D.; Wang, Y. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of Defeat Scale in men who have sex with men. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 41, 793–798. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tong, X.; An, D.; McGonigal, A.; Park, S.P.; Zhou, D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy–ScienceDirect. Epilepsy Res. 2016, 120, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Lukai; Rongjing, D.; Dayi, H.; Sheng, L. GW25-e4488 The value of Chinese version GAD-7 and PHQ-9 to screen anxiety and depression in cardiovascular outpatients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, C222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, Q.Z.; Yan-Ling, H.E.; Liu, H.; Miao, J.M.; Chen, J.X.; Hai-Nan, X.U. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item(GAD-7) scale in screening anxiety disorders in outpatients from traditional Chinese internal department. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2013, 27, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorgvinsson, T.; Kertz, S.J.; Bigda-Peyton, J.S.; McCoy, K.L.; Aderka, I.M. Psychometric properties of the CES-D-10 in a psychiatric sample. Assessment 2013, 20, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohebbi, M.; Nguyen, V.; Mcneil, J.J.; Woods, R.L.; Nelson, M.R.; Shah, R.C.; Storey, E.; Murray, A.M.; Reid, C.M.; Kirpach, B. Psychometric properties of a short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D-10) scale for screening depressive symptoms in healthy community dwelling older adults. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2017, 51, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, E.C.; Davies, T.; Lund, C. Validation of the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almanasreh, E.; Moles, R.; Chen, T.F. Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Focus on research methods. is the cvi an acceptable indicator of content validity? appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nur. Res. 1986, 35, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, L.L. Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1992, 5, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Sahibuddin, S.; Jalaliyoon, N. Exploratory factor analysis; concepts and theory. Adv. Appl. Pure Math. 2022, 27, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Pett, M.A.; Lackey, N.R.; Sullivan, J.J. Making Sense of Factor Analysis: The Use of Factor Analysis for Instrument Development in Health Care Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, R.K.; Roberts, J.K. Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Published Research. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; International Standard Book Number: 1-59147-093-5; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J.W. What is rotating in exploratory factor analysis? Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2015, 20, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 24, p. 899. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, R.D.; Valero-Mora, P. Determining the number of factors to retain in EFA: An easy-to-use computer program for carrying out parallel analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1993, 154, 132–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumaher, M.; Milani, D.; Alexandre, N. Psychometric properties evaluation of the Psychological Empowerment Instrument in a Brazilian context. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Green, S.B. Coefficient alpha: A reliability coefficient for the 21st century? J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2011, 29, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret, L.; Mesbah, M.; Chwalow, J.; Lellouch, J. Internal validation of a measurement scale: Relation between principal component analysis, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and intra-class correlation coefficient. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 1993, 41, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ju, X.; Brennan, D.; Parker, E.; Chrisopoulos, S.; Jamieson, L. Confirmatory factor analysis of the health literacy in dentistry scale (HeLD) in the Australian population. Community Dent Health 2018, 35, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: A Comment. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segars, A.H. Assessing the unidimensionality of measurement: A paradigm and illustration within the context of information systems research. Omega 1997, 25, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zahedi, F.M. Individuals’ Internet Security Perceptions and Behaviors: Polycontextual Contrasts Between the United States and China. MIS Q. 2016, 40, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasan, S.I.; Yee, A.; Rinaldi, A.; Azham, A.A.; Mohd Hairi, F.; Amer Nordin, A.S. Prevalence of common mental health issues among migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwerier, E.; Crombez, G.; Van Damme, S.; Goubert, L.; Vogelaers, D.; Evers, A.W. The Construct Validity of the Illness Cognition Questionnaire: The Robustness of the Three-factor Structure Across Patients with Chronic Pain and Chronic Fatigue. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2010, 17, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loo, R. A psychometric evaluation of the General Decision-Making Style Inventory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000, 29, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, D. Defeat and entrapment as predictors of depression and suicidal ideation versus hopelessness and helplessness. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 111, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willner, P.; Goldstein, R.C. Mediation of depression by perceptions of defeat and entrapment in high-stress mothers. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 2001, 74, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagioti, M.; Gooding, P.A.; Tarrier, N. Hopelessness, defeat, and entrapment in posttraumatic stress disorder: Their association with suicidal behavior and severity of depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012, 200, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Taylor, P.J.; Wood, A.M.; Schulz, J. A meta-analysis of perceptions of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety problems, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 184, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Participants n = 1805 | Group 1 n = 856 | Group 2 n = 949 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Median (IQR) | 32 (27.0, 37.0) | 32 (27, 36) | 32.0 (27, 37) | 0.726 |

| Gender | 0.978 | |||

| Male | 1214 (67.3%) | 576 (67.3%) | 638 (67.2%) | |

| Female | 591 (32.7%) | 280 (32.7%) | 311 (32.8%) | |

| Nation | 0.256 | |||

| Han nationality | 1524 (84.4%) | 714 (83.4%) | 810 (85.4%) | |

| Ethnic minority | 281 (15.6%) | 142 (16.6%) | 139 (14.6%) | |

| Education | 0.198 | |||

| Primary School and below | 64 (3.5%) | 30 (3.5%) | 34 (3.6%) | |

| Junior High School | 995 (55.1%) | 493 (57.6%) | 502 (52.9%) | |

| High School | 585 (32.4%) | 259 (30.3%) | 326 (34.4%) | |

| junior college | 94 (5.2%) | 43 (5.0%) | 51 (5.4%) | |

| Undergraduate | 19 (1.1%) | 12 (1.4%) | 7 (0.7%) | |

| Other | 48 (2.7%) | 19 (2.2%) | 29 (3.1%) | |

| Marriage | 0.759 | |||

| Unmarried with no boyfriend/girlfriend | 555 (30.7%) | 260 (30.4%) | 295 (31.1%) | |

| Unmarried but with a boyfriend/girlfriend | 164 (9.1%) | 88 (10.3%) | 76 (8.0%) | |

| Married | 967 (53.6%) | 441 (51.5%) | 526 (55.4%) | |

| Divorce/widowhood | 47 (2.6%) | 24 (2.8%) | 23 (2.4%) | |

| Others | 72 (4.0%) | 43 (5.0%) | 29 (3.1%) | |

| Wage ($) * | 0.201 | |||

| Unknown | 56 (3.1%) | 17 (2.0%) | 39 (4.1%) | |

| Less than 154.67 | 25 (1.4%) | 13 (1.5%) | 12 (1.3%) | |

| 154.67–463.85 | 141 (7.8%) | 49 (5.7%) | 92 (9.7%) | |

| 464.00–773.18 | 1099 (60.9%) | 552 (64.5%) | 547 (57.6%) | |

| 773.34–1082.51 | 447 (24.8%) | 214 (25.0%) | 233 (24.6%) | |

| 1082.67–1546.52 | 29 (1.6%) | 8 (0.9%) | 21 (2.2%) | |

| Over 1546.67 | 8 (0.4%) | 3 (0.4%) | 5 (0.5%) |

| Items | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 | Expert 4 | Expert 5 | Expert 6 | Expert 7 | Expert 8 | Number of Agreements | Item-CVI1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.875 |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 0.875 |

| 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 9 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.875 |

| 12 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 13 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 14 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 15 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 1.000 |

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.000 |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cum% | Total | % of Variance | Cum% | Total | % of Variance | Cum% | |

| 1 | 8.180 | 51.126 | 51.126 | 8.180 | 51.126 | 51.126 | 7.882 | 49.263 | 49.263 |

| 2 | 1.773 | 11.082 | 62.208 | 1.773 | 11.082 | 62.208 | 2.071 | 12.944 | 62.208 |

| 3 | 0.994 | 6.213 | 68.421 | ||||||

| 4 | 0.928 | 5.802 | 74.222 | ||||||

| 5 | 0.535 | 3.341 | 77.564 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.466 | 2.915 | 80.479 | ||||||

| 7 | 0.444 | 2.776 | 83.256 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.374 | 2.338 | 85.593 | ||||||

| 9 | 0.360 | 2.250 | 87.843 | ||||||

| 10 | 0.342 | 2.136 | 89.980 | ||||||

| 11 | 0.336 | 2.099 | 92.079 | ||||||

| 12 | 0.313 | 1.954 | 94.033 | ||||||

| 13 | 0.279 | 1.742 | 95.775 | ||||||

| 14 | 0.257 | 1.608 | 97.383 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.227 | 1.418 | 98.801 | ||||||

| 16 | 0.192 | 1.199 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Two-Factor Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| item1 | I feel that I have not made it in life | 0.630 | |

| item2 | I feel that I am a successful person (R) | 0.865 | |

| item3 | I feel defeated by life | 0.726 | |

| item4 | I feel that I am basically a winner (R) | 0.881 | |

| item5 | I feel that I have lost my standing in the world | 0.664 | |

| item6 | I feel that life has treated me like a punchbag | 0.698 | |

| item7 | I feel powerless | 0.807 | |

| item8 | I feel that my confidence has been knocked out of me | 0.753 | |

| item9 | I feel able to deal with whatever life throws at me (R) | 0.593 | |

| item10 | I feel that I have sunk to the bottom of the ladder | 0.773 | |

| item11 | I feel completely knocked out of action | 0.805 | |

| item12 | I feel that I am one of life’s losers | 0.863 | |

| item13 | I feel that I have given up | 0.819 | |

| item14 | I feel down and out | 0.857 | |

| item15 | I feel I have lost important battles in life | 0.832 | |

| item16 | I feel that there is no fight left in me | 0.814 | |

| One-Factor Model | Two-Factor Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | ||

| item1 | I feel that I have not made it in life | 0.587 | 0.586 | |

| item2 | I feel that I am a successful person (R) | 0.137 | 0.735 | |

| item3 | I feel defeated by life | 0.664 | 0.664 | |

| item4 | I feel that I am basically a winner (R) | 0.148 | 0.762 | |

| item5 | I feel that I have lost my standing in the world | 0.670 | 0.670 | |

| item6 | I feel that life has treated me like a punchbag | 0.650 | 0.650 | |

| item7 | I feel powerless | 0.789 | 0.788 | |

| item8 | I feel that my confidence has been knocked out of me | 0.692 | 0.691 | |

| item9 | I feel able to deal with whatever life throws at me (R) | 0.237 | 0.434 | |

| item10 | I feel that I have sunk to the bottom of the ladder | 0.747 | 0.733 | |

| item11 | I feel completely knocked out of action | 0.788 | 0.788 | |

| item12 | I feel that I am one of life’s losers | 0.837 | 0.838 | |

| item13 | I feel that I have given up | 0.827 | 0.827 | |

| item14 | I feel down and out | 0.880 | 0.880 | |

| item15 | I feel I have lost important battles in life | 0.845 | 0.845 | |

| item16 | I feel that there is no fight left in me | 0.824 | 0.825 | |

| Index | Acceptable Value | One-Factor Model | Two-Factor Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | <5 | 9.751 | 5.343 |

| GFI | >0.9 | 0.883 | 0.932 |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.910 | 0.956 |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.901 | 0.946 |

| RFI | >0.9 | 0.881 | 0.935 |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.910 | 0.956 |

| TLI | >0.9 | 0.892 | 0.946 |

| sRMR | <0.08 | 0.0695 | 0.0522 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.096 | 0.068 |

| Dependent Variables | Covariates | β | S.E. | Wald | df | p | OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | DS score | 0.127 | 0.007 | 315.117 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.136 (1.120, 1.152) |

| Anxiety | DS score | 0.131 | 0.007 | 318.743 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.140 (1.124, 1.156) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Hu, F.; Xu, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Reliability and Validity of the Defeat Scale among Internal Migrant Workers in China: Decadence and Low Sense of Achievement. Healthcare 2023, 11, 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060781

Liu S, Chen Y, Chen Y, Hu T, Wang Z, Wang R, Hu F, Xu C, Yu X, Liu Y, et al. Reliability and Validity of the Defeat Scale among Internal Migrant Workers in China: Decadence and Low Sense of Achievement. Healthcare. 2023; 11(6):781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060781

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shangbin, Yingjie Chen, Yaqi Chen, Tian Hu, Zixin Wang, Rongxi Wang, Fan Hu, Chen Xu, Xiaoyue Yu, Yujie Liu, and et al. 2023. "Reliability and Validity of the Defeat Scale among Internal Migrant Workers in China: Decadence and Low Sense of Achievement" Healthcare 11, no. 6: 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060781