Factors Affecting Users’ Continuous Usage in Online Health Communities: An Integrated Framework of SCT and TPB

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Online Health Communities and Continuous Usage

2.2. Social Cognitive Theory

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior

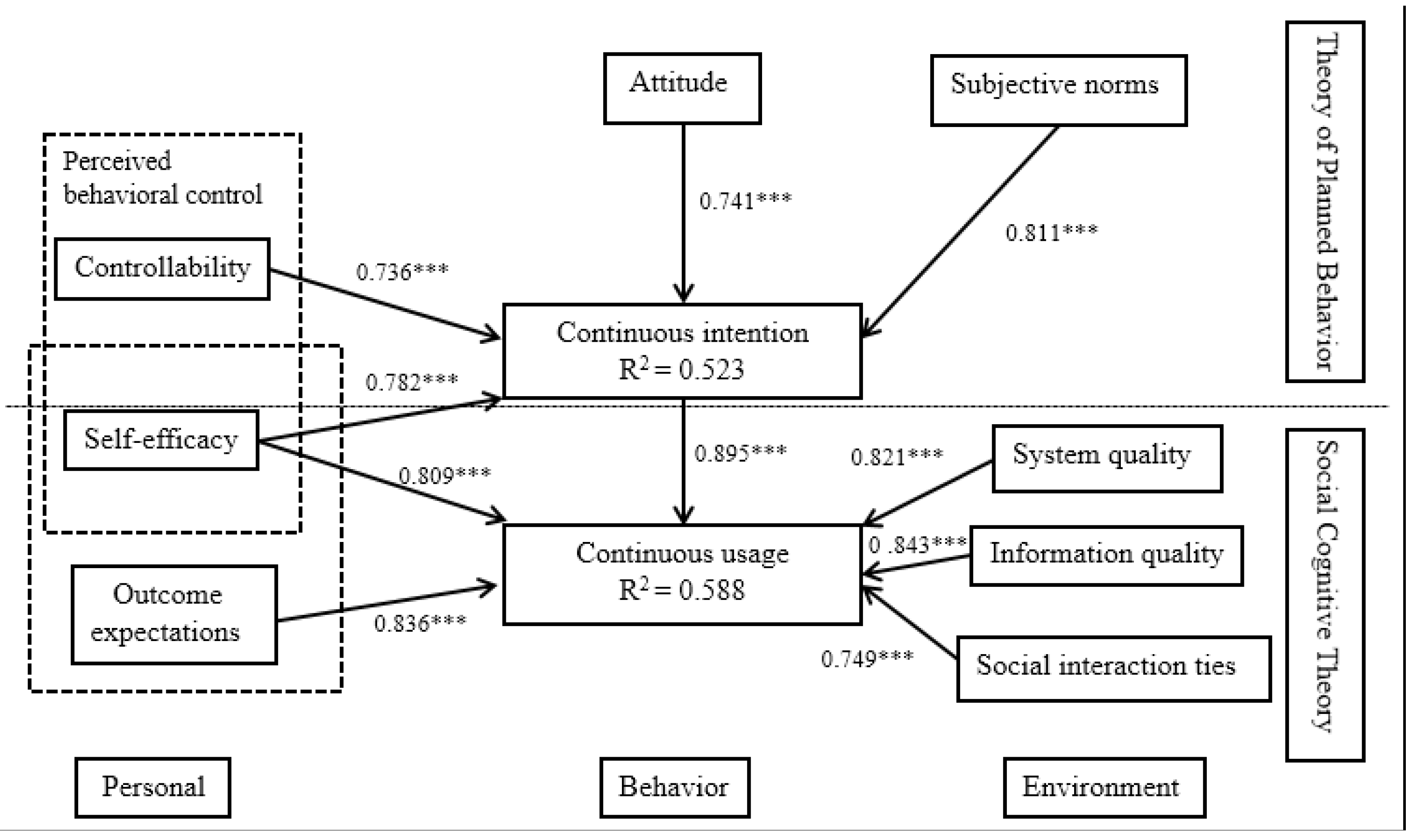

3. Research Hypotheses

Relationship between Perceived Behavior Control and Continuous Use Intention

4. Methods

4.1. Instrument Development

4.2. Analysis Tool Selection

4.3. Data Collection and Respondent Profile

4.4. Common Method Bias and Non-Response Bias Test

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Principal Findings

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OHC | Online Health Community |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

Appendix A. Measurement Scale

| Component and Measurement Number | Scale |

|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | I could easily operate in OHCs and it is important to me |

| I know enough to operate in OHCs and it is important to me | |

| I would feel comfortable using OHCs and it is important to me | |

| Controllability | I have the network to use the OHCs and it is important to me |

| I have the time to use the OHCs and it is important to me | |

| I have the money to use the OHCs and it is important to me | |

| Attitude | Using the OHCs is good |

| Using the system is favorable | |

| Using the OHCs is a wise idea | |

| Subjective norms | People who influence my behavior (would think/think) that using OHCs would be a wise idea |

| People who are important to me (would think/think) that I should use the OHCs | |

| People who are in my social circle (would think/think) that using OHCs is a good idea | |

| Outcome expectations | Continuous usage OHCs will be helpful to the successful functioning of the community |

| Continuous usage OHCs would help the community continue its operation in the future | |

| Continuous usage OHCs would help the community grow | |

| Continuous intention | I intend to continue using OHCs rather than discontinue their use |

| I intend to continue using OHCs than use any alternative means | |

| I plan to continue using OHCs to get more information when i need | |

| Continuous usage | I currently use the OHCs |

| I currently use different applications related to healthy | |

| I currently spend much time on OHCs when i need | |

| System quality | The OHCs system performed reliably for me |

| The OHCs system was accessible to me | |

| The OHCs system answered my requests quickly | |

| Overall, i would give the quality of the OHCs website system a high rating | |

| Information quality | The information provided by the OHCs is related to my search |

| The information provided by the OHCs is current | |

| The information provided by the OHCs is trustworthy | |

| In general, the OHCs provided me with high-quality information | |

| Social interaction ties | I maintain close social relationships with some members in OHCs |

| I spend a lot of time interacting with some members in this OHCs | |

| I know some members in this OHCs on a personal level | |

| I have frequent communication with some members in OHCs |

References

- Potts, H.W.W. Online support groups: An overlooked resource for patients. Health Inf. Internet 2005, 44, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, J.M.; Gao, G.; Agarwal, R. The Creation of Social Value: Can an Online Health Community Reduce Rural–Urban Health Disparities? MIS Q. 2016, 40, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, D.; Jonker, J.; Faber, N. Outside-in constructions of organizational legitimacy: Sensitizing the influence of evaluative judgments through mass self-communication in online communities. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2018, 12, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, H.; Seymour, B.; Fish, S.A., 2nd; Robinson, E.; Zuckerman, E. Digital Health Communication and Global Public Influence: A Study of the Ebola Epidemic. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22 (Suppl. 1), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Gu, Y.; Hong, W.; Ping, Z.S.; Liang, C.; Gu, D. How COVID-19 Affects the Willingness of the Elderly to Continue to Use the Online Health Community: A Longitudinal Survey. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2022, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jina, X.-L.; Lee, M.K.O.; Cheung, C.M.K. Predicting continuance in online communities: Model development and empirical test. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2010, 29, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, R. Impact of Physician-Patient Communication in Online Health Communities on Patient Compliance: Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.M.; Km, M.A.S. Knowledge Sharing in Cyberspace: Virtual Knowledge Communities. In Practical Aspects of Knowledge Management; PAKM 2002. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Karagiannis, D., Reimer, U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2569. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Deng, Z.; Chen, X. knowledge sharing motivations in online health communities: A comparative study of health professionals and normal users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Examining users’ knowledge sharing behaviour in online health communities. Data Technol. Appl. 2019, 53, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, S.; Sastry, N.; Coulson, N.S.; Taylor, S.J.; Patel, A.; Duschinsky, R.; Anand, A.; Jameson Evans, M.; Griffiths, C.J.; Sheikh, A.; et al. Addendum to the Acknowledgements: How Online Communities of People with Long-Term Conditions Function and Evolve: Network Analysis of the Structure and Dynamics of the Asthma UK and British Lung Foundation Online Communities. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamakiotis, P.; Petrakaki, D.; Panteli, N. Social value creation through digital activism in an online health community. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 31, 94–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney-Krichmar, D.; Preece, J. A multilevel analysis of sociability, usability, and community dynamics in an online health community. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2005, 12, 201–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney-Krichmar, D.; Preece, J. The meaning of an online health community in the lives of its members: Roles, relationships and group dynamics. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2002 International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS’02). Social Implications of Information and Communication Technology. Proceedings (Cat. No. 02CH37293), Raleigh, NC, USA, 6–8 June 2002; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L.; Yiwei, Z.; Yixuan, X. Support-Seeking Strategies and Social Support Provided in Chinese Online Health Communities Related to COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 783135. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.M.; Hribar, C.A.; Hayes, S.; Bhowmick, A.; Herbert, L.B. Come for Information, Stay for Support: Harnessing the Power of Online Health Communities for Social Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Fan, X.; Ji, R.; Jiang, Y. Perceived Community Support, Users’ Interactions, and Value Co-Creation in Online Health Community: The Moderating Effect of Social Exclusion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, K.; Street, N. Analyzing and predicting user participations in online health communities: A social support perspective. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, E.; Han, J. Exploring the Effect of Market Conditions on Price Premiums in the Online Health Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebland, S.U.E.; Wyke, S. Health and Illness in a Connected World: How Might Sharing Experiences on the Internet Affect People’s Health? Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 219–249. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23266510 (accessed on 2 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Audrain-Pontevia, A.-F.; Menvielle, L. Do online health communities enhance patient–physician relationship? An assessment of the impact of social support and patient empowerment. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2018, 31, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.; Kwon, B.C.; Yi, J.S.; Choo, J.; Huh, J. Toward predicting social support needs in online health social networks. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpinganjira, M. Willingness to reciprocate in virtual health communities: The role of social capital, gratitude and indebtedness. Serv. Bus. 2019, 13, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Lederman, R. Online health communities: How do community members build the trust required to adopt information and form close relationships? Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, B.; Zhu, Q. Health information privacy concerns, antecedents, and information disclosure intention in online health communities. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, N.; van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.; Kelders, S.M.; Brandenburg, B.J.; Seydel, E.R. Factors influencing the use of a Web-based application for supporting the self-care of patients with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, K.T.; McCray, A.T.; Safran, C. Modeling the temporal evolution of an online cancer forum. In Proceedings of the First ACM International Health Informatics Symposium, Arlington, VA, USA, 11–12 November 2010; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Potnis, D.; Halladay, M. Information practices of administrators for controlling information in an online community of new mothers in rural America. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 73, 1621–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. Patient Continued Use of Online Health Care Communities: Web Mining of Patient-Doctor Communication. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S. Understanding relationship commitment and continuous knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 26, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J. Users’ Intention to Continue Using Online Mental Health Communities: Empowerment Theory Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Miyao, M.; Ozaki, H.; Tobia, S.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Frattini, F. The role of open innovation hubs and perceived collective efficacy on individual behaviour in open innovation projects. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2022, 31, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdizadeh, S.M.; Sany SB, T.; Sarpooshi, D.R.; Jafari, A.; Mahdizadeh, M. Predictors of preventive behavior of nosocomial infections in nursing staff: A structural equation model based on the social cognitive theory. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fan, T. Understanding the Factors Influencing Patient E-Health Literacy in Online Health Communities (OHCs): A Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-P. Learning Virtual Community Loyalty Behavior from a Perspective of Social Cognitive Theory. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2010, 26, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A.; Huff, S. Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: A longitudinal study. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, K.-C.; Chen, M.-C. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intention: Perceived playfulness and perceived flow as mediators. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2011, 10, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Davison, R.M. What Drives Trust Transfer? The Moderating Roles of Seller-Specific and General Institutional Mechanisms. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 20, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. The relative importance of website design quality and service quality in determining consumers’ online repurchase behavior. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2009, 26, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, E.T.G. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40 Pt 4, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Chiu, C. Predicting electronic service continuance with a decomposed theory of planned behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2004, 23, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Ju, T.; Yen, C.; Chang, C. Knowledge sharing behaviour in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self—Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D.; Sheeran, P.; Conner, M.; Finlay, K. Evidence that perceived behavioural control is a multidimensional construct: Perceived control and perceived difficulty. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 41, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.K.; Li, N.H.; Wu, K.S. An empirical research of Kinmen tourists’ behavioral tendencies model—A case-validation in causal modeling. J. Tour. Stud. 2005, 11, 355–384. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.; Chervany, N. Information technology adoption across time: A cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Premkumar, G. Understanding changes in belief and attitude toward information technology usage: A theoretical model and longitudinal test. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.C. The management of sports tourism: A causal modeling test of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 474–491. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Geng, L.; Xu, Y.; Meline, N.N. The Influence of Environmental Values on Consumer Intentions to Participate in Agritourism—A Model to Extend TPB. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2022, 35, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P. The influence process of electronic word-of-mouth on traveller’s visit intention: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2016, 16, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.P. Integration of TAM, TPB, and Self-image to Study Online Purchase Intentions in an Emerging Economy. Int. J. Online Mark. 2015, 5, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, Z.; Von Krogh, G.; Kim, S. Knowledge Sharing in an Online Community of Volunteers: The Role of Community Munificence. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2012, 9, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.-C. Online stickiness: Its antecedents and effect on purchasing intention. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2007, 26, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Khan, A.N.; Ali, A.; Khan, N.A. Consequences of Cyberbullying and Social Overload while Using SNSs: A Study of Users’ Discontinuous Usage Behavior in SNSs. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 22, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z. Understanding online knowledge community user continuance:A social cognitive theory perspective. Data Technol. Appl. 2018, 52, 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Davison, R.M. The role of website quality and social capital in building buyers’ loyalty. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yan, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. How users adopt healthcare information: An empirical study of an online Q&A community. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 86, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Y.-Y.; Fang, K. The use of a decomposed theory of planned behavior to study Internet banking in Taiwan. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Chun, J.U.; Song, J. Investigating the role of attitude in technology acceptance from an attitude strength perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2008, 29, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Han, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, C.; Reinhardt, J.D. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Online Health Consultation Services: The Role of Subjective Norm, Trust, Perceived Benefit, and Offline Habit. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.G. Examining an extended duality perspective regarding success conditions of IT service. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Benbasat, I.; Cenfetelli, R.T. Integrating service quality with system and information quality: An empirical test in the e-service context. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Lin, C.-P. A unified model of IT continuance: Three complementary perspectives and crossover effects. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Perols, J.; Sanford, C. Information Technology Continuance: A Theoretic Extension and Empirical Test. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2008, 49, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 51st Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. Available online: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2023/0303/c88-10757.html (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Yan, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.; Overton, T.S. Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 39–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.K.; Benyoucef, M.; Zhao, S.J. Building brand loyalty in social commerce: The case of brand microblogs. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Gong, Y.Y. Social capital, motivations, and knowledge sharing intention in health Q&A communities. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1536–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Hong, Y. Evolutionary Game—Theoretic Approach for Analyzing User Privacy Disclosure Behavior in Online Health Communities. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. General Office of the State Council’s Views on Promoting the Development of “Internet Plus Medical Health”. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-04/28/content_5286645.htm (accessed on 28 April 2018).

- National Healthcare Security Administration. Guidance from National Healthcare Security Administration on Improving the Price of “Internet Plus” Medical Services and Medical Insurance Payment Policies. Available online: http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2019/8/30/art_37_1707.html (accessed on 30 August 2019).

| Demographic Characteristics | Participants, n(%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <20 | 17 (3.5) |

| 20–29 | 222 (46.3) |

| 30–39 | 167 (34.8) |

| 40–49 | 61 (12.7) |

| 50–59 | 10 (2.1) |

| 60 and above | 3 (0.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 224 (46.7) |

| Female | 256 (53.3) |

| Living area | |

| Urban | 310 (64.6) |

| Rural | 170 (35.4) |

| Education | |

| Junior hihg school and below | 15 (3.1) |

| High school | 50 (10.4) |

| Bachelor’ degree | 209 (43.5) |

| Master’ degree | 173 (36.1) |

| Doctor’s degree and above | 33 (6.9) |

| Constructs | Item | Standard Factor Loading | Variance Inflation Factor | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | Square Root of AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | S1 | 0.93 | 1.437 | 0.916 | 0.893 | 0.702 | 0.838 |

| S2 | 0.89 | ||||||

| S3 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Controllability | C1 | 0.96 | 1.533 | 0.932 | 0.926 | 0.732 | 0.856 |

| C2 | 0.91 | ||||||

| C3 | 0.93 | ||||||

| Attitude | A1 | 0.91 | 1.426 | 0.907 | 0.836 | 0.721 | 0.849 |

| A2 | 0.89 | ||||||

| A3 | 0.93 | ||||||

| Subjective norms | SN1 | 0.96 | 1.506 | 0.918 | 0.917 | 0.717 | 0.847 |

| SN2 | 0.86 | ||||||

| SN3 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Continuous intention | CI1 | 0.92 | 1.455 | 0.924 | 0.913 | 0.785 | 0.886 |

| CI2 | 0.94 | ||||||

| CI3 | 0.89 | ||||||

| Continuous usage | CB1 | 0.93 | 1.328 | 0.915 | 0.907 | 0.752 | 0.867 |

| CB2 | 0.91 | ||||||

| CB3 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Outcome expectations | OE1 | 0.91 | 1.314 | 0.910 | 0.914 | 0.783 | 0.885 |

| OE2 | 0.92 | ||||||

| OE3 | 0.88 | ||||||

| System quality | SQ1 | 0.88 | 1.306 | 0.905 | 0.903 | 0.724 | 0.851 |

| SQ2 | 0.89 | ||||||

| SQ3 | 0.92 | ||||||

| SQ4 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Information quality | IQ1 | 0.95 | 1.369 | 0.922 | 0.924 | 0.741 | 0.861 |

| IQ2 | 0.93 | ||||||

| IQ3 | 0.84 | ||||||

| IQ4 | 0.89 | ||||||

| Social interaction ties | ST1 | 0.92 | 1.411 | 0.916 | 0.886 | 0.794 | 0.891 |

| ST2 | 0.93 | ||||||

| ST3 | 0.89 | ||||||

| ST4 | 0.91 |

| Variable | SE | C | SN | CI | CU | OE | SQ | IQ | SIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 0.838 | ||||||||

| C | 0.529 | 0.856 | |||||||

| A | 0.473 | 0.533 | |||||||

| SN | 0.556 | 0.654 | 0.847 | ||||||

| CI | 0.689 | 0.387 | 0.652 | 0.886 | |||||

| CU | 0.731 | 0.571 | 0.630 | 0.651 | 0.867 | ||||

| OE | 0.322 | 0.388 | 0.407 | 0.496 | 0.611 | 0.885 | |||

| SQ | 0.546 | 0.476 | 0.606 | 0.569 | 0.357 | 0.521 | 0.851 | ||

| IQ | 0.433 | 0.519 | 0.618 | 0.393 | 0.408 | 0.637 | 0.593 | 0.861 | |

| SIT | 0.497 | 0.475 | 0.425 | 0.544 | 0.511 | 0.706 | 0.436 | 0.675 | 0.891 |

| Variables | R Square | Control Variables Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Control Variables | Without Control Variables | ΔR² a | f2 b | Effect | |

| CI | 0.523 | 0.521 | 0.002 | 0.015 | Insignificant |

| CU | 0.588 | 0.583 | 0.005 | 0.008 | Insignificant |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | t Test | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | 0.736 | 14.31 | <0.001 |

| H1b | 0.782 | 14.66 | <0.001 |

| H2 | 0.741 | 14.24 | <0.001 |

| H3 | 0.811 | 16.56 | <0.001 |

| H4 | 0.895 | 17.79 | <0.001 |

| H5a | 0.809 | 16.31 | <0.001 |

| H5b | 0.836 | 16.95 | <0.001 |

| H6a | 0.821 | 16.73 | <0.001 |

| H6b | 0.843 | 17.32 | <0.001 |

| H6c | 0.749 | 14.57 | <0.001 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | p Value | CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||

| SE → CI | 0.736 | <0.001 | 0.631–0.824 |

| Controllability → CI | 0.782 | <0.001 | 0.675–0.879 |

| Attitude → CI | 0.741 | <0.001 | 0.639–0.813 |

| SN → CI | 0.811 | <0.001 | 0.719–0.903 |

| CI → CU | 0.895 | <0.001 | 0.787–0.985 |

| SE → CU | 0.809 | <0.001 | 0.723–0.856 |

| OE → CU | 0.836 | <0.001 | 0.748–0.889 |

| SQ → CU | 0.821 | <0.001 | 0.736–0.917 |

| IQ → CU | 0.843 | <0.001 | 0.756–0.836 |

| SIT → CU | 0.749 | <0.001 | 0.685–0.793 |

| Indirect effect | |||

| SE → CU | 0.563 | <0.001 | 0.489–0.612 |

| Controllability → CU | 0.498 | <0.001 | 0.399–0.528 |

| Attitude → CU | 0.577 | <0.001 | 0.496–0.654 |

| SN → CU | 0.374 | <0.001 | 0.306–0.452 |

| Total effect | |||

| SE → CU | 0.563 | <0.001 | 0.489–0.612 |

| Controllability → CU | 0.498 | <0.001 | 0.399–0.528 |

| Attitude → CU | 0.577 | <0.001 | 0.496–0.654 |

| SN → CU | 0.374 | <0.001 | 0.306–0.452 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Liu, R. Factors Affecting Users’ Continuous Usage in Online Health Communities: An Integrated Framework of SCT and TPB. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091238

Cao Z, Zheng J, Liu R. Factors Affecting Users’ Continuous Usage in Online Health Communities: An Integrated Framework of SCT and TPB. Healthcare. 2023; 11(9):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091238

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Zhuolin, Jian Zheng, and Renjing Liu. 2023. "Factors Affecting Users’ Continuous Usage in Online Health Communities: An Integrated Framework of SCT and TPB" Healthcare 11, no. 9: 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091238

APA StyleCao, Z., Zheng, J., & Liu, R. (2023). Factors Affecting Users’ Continuous Usage in Online Health Communities: An Integrated Framework of SCT and TPB. Healthcare, 11(9), 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091238