Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior among Medically Underserved Women: Effectiveness of 3R Communication Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening

1.2. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening

1.3. Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Recruitment

- (a)

- The face-to-face method was used to recruit some of the women at community gatherings such as local food pantries and churches. During our first contact with the potential participants, we gave them the study recruitment flyer which had the study eligibility criteria (in English and Spanish) and our contact information. Upon reading it, some of them instantly informed us of their willingness to participate in the study and gave us their phone number. Others took the flyers with them and made decisions afterward. Women were recruited once initial inclusion qualifications were determined.

- (b)

- The snowball method was used when a woman completed the study; we asked her if she would like to introduce anybody, including friend(s), family member(s), or co-worker(s), to the study. Some of the participants offered to introduce the study to women in their network. When we received the contact information of the women referred, we followed up with them and assessed their eligibility based on the study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria. In both recruitment methods, we contacted the women through the phone numbers they gave to us, and once their eligibility had been determined, we discussed informed consent with them and scheduled an intervention presentation time for those who qualified and were willing to participate. We had a designated facility in the community area where the presentations were conducted. We gave the address of the facility to the women, and they drove to the facility on their scheduled date. We provided transportation to those women who did not have access to transportation. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University.

2.2. Intervention Description and Delivery

2.3. Intervention Delivery

2.4. Measures

2.5. Interviews Guide

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Self-Sampling Outcomes

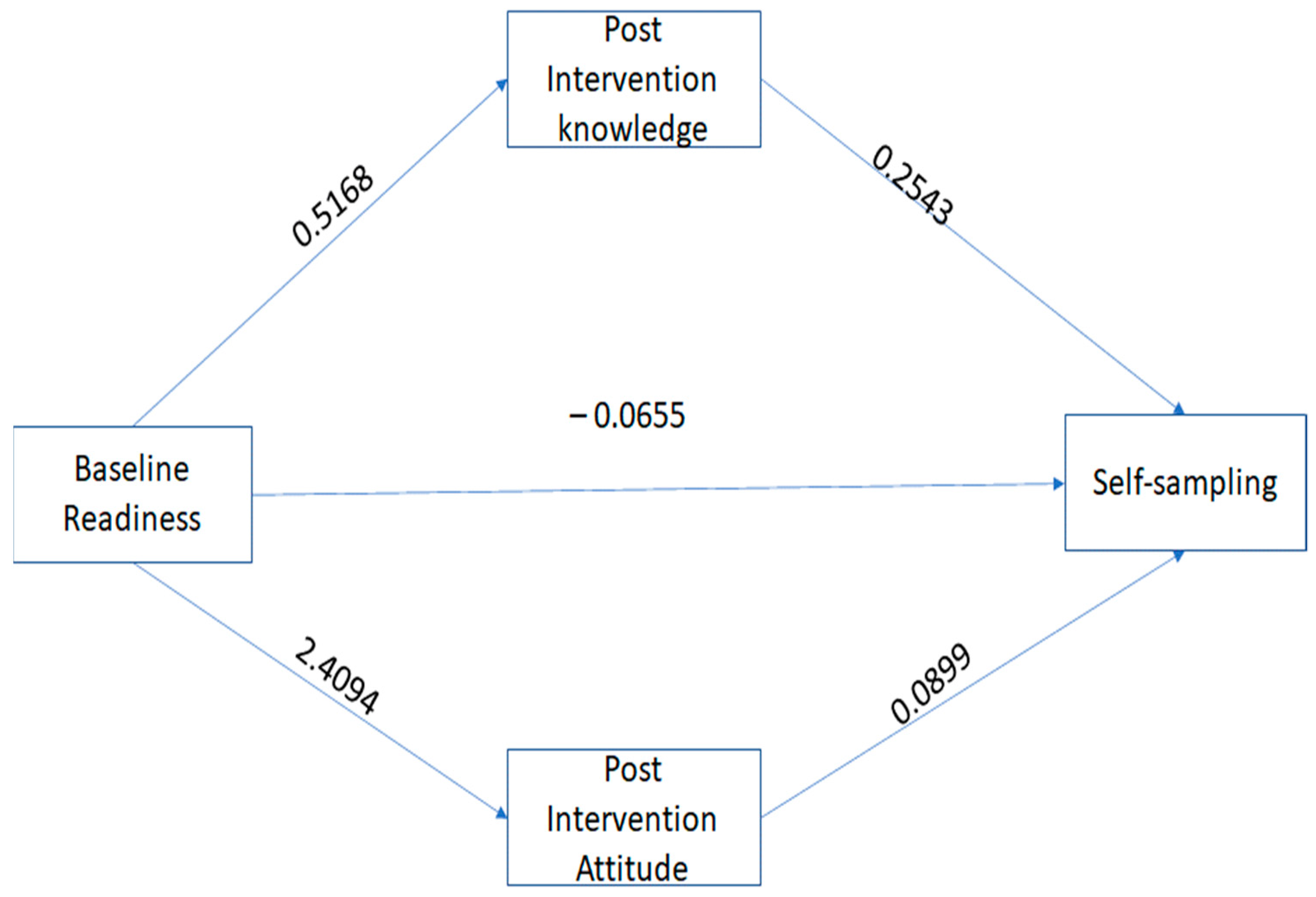

3.3. Mediation Analysis

3.4. Mixed Method: Survey and Interview Results

3.4.1. Theme 1: Acceptability

“Reforming and being proactive and how you can change what you have been doing”. “It was educational for me. I like the step-by-step approach to the information presented. The diagram gives a clear picture for me to understand and explain to other people. The presentation is not too long, and it was straight to the point”.(A 33-year-old participant)

3.4.2. Theme 2: Appropriateness

“The presentation was clear, precise, and very informative, and I like that [the presenter] asked questions along the way. The information I received today was helpful and as a woman, I have a daughter, I will be able to use the information I learned today to help my daughter when she comes up against it”.(A 39-year-old participant)

3.4.3. Theme 3: Feasibility

“I will tell others how easy it was and the information I learned, easy to understand and it was relieving to learn those things. I will recommend it to people because I think a lot of people are busy and this sample at-home kit makes it easier for people to do it at home when their lives are fast and chaotic” (A 53-year-old participant). “I will be open to do self-sampling and I believe a lot of women will do self-sampling because they are not comfortable with doctors taking the samples”.(A 44-year-old participant)

“I had no idea about self-sampling but after I learned about it, it is convenient, less embarrassing, unlike going to the actual doctor and lying on the exam table for examination. It is not invasive taking it and it is more comfortable and easier to take it”. (A 34-year-old participant) “The presentation helps me to decide to take the sample because I want to know my status and be educated. I wanted to know if I carry the virus” (A 53-year-old participant). Before taking the sample, I was very nervous that I was going to do this to my body, and I don’t want to do that to my body. After I did it, I found out that it was not difficult at all. It was easy, one, two, three, you are done”.(A 55-year-old participant)

“I feel like a learned a lot, just valuable information I didn’t know before about cervical cancer and HPV that I didn’t know and preventative things to be proactive about it” (A 53-year old participant). Wow, I am glad that I took part in the study because I didn’t know anything about the virus and how you can get it. Why nobody has told us anything like this. This is great information to learn” (A 34-year-old participant). “The presentation created awareness for me to know that I may be at risk of having the virus, aware that HPV is so common”.(A 43-year-old participant)

“Barriers to taking self-sampling could be not understanding what to do and some people are not comfortable with their own body, the cost for self-sampling around $45 can be expensive for some people to buy but compared to doctors’ examination it is less expensive” (A 42-year-old participant). “Some of the barriers can be fear of knowing they have the virus” (A 33-year-old participant). “I don’t see any barriers why any woman wouldn’t want to take it. If women doubt the results, it could be a barrier to take it but to me I will encourage women to take it because it was easier and comfortable to take it. I will recommend it to people to take it”.(A 36-year-old participant)

“To me, it is easier to use the self-sampling because of the way the economy is, people are being laid off and people are not having insurance or anything. I think self-sampling is good for those who don’t have health insurance because they can’t afford to go to their doctors but can buy the kit and use it at home.” (A 39-year-old participant). “…I think a lot of people are busy and this sample at-home kit makes it easier for people to do it at home when their lives are fast and chaotic”.(A 53-year-old participant)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Denny, L.; Herrero, R.; Levin, C.; Kim, J.J. Cervical Cancer. In Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3); Gelband, H., Jha, P., Sankaranarayanan, R., Horton, S., Eds.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1 November 2015; Chapter 4. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343648/ (accessed on 26 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Caskey, R.; Lindau, S.T.; Alexander, G.C. Knowledge and early adoption of the HPV vaccine among girls and young women: Results of a national survey. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahasrabuddhe, V. April 10–12. HPV Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening in the United States. [Conference Session). Dusseldorf, Germany. In Proceedings of the Eurogin 2022 Conference; Available online: https://www.eurogin.com/content/dam/Informa/eurogin/2022/pdf/Eurogin2022_CongressBook_Program.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Viens, L.J.; Henley, S.J.; Watson, M.; Markowitz, L.E.; Thomas, C.C.; Thompson, T.D.; Razzaghi, H.; Saraiya, M. Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers—United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV and Cancer: HPV-Associated Cervical Cancer Rates by Race and Ethnicity. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cervical.htm (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Yu, L.; Sabatino, S.A.; White, M.C. Rural-Urban and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Invasive Cervical Cancer Incidence in the United States, 2010–2014. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2018–2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-hispanics-and-latinos/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-hispanics-and-latinos-2018-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2019–2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2019-2021.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Bradley, C.J.; Given, C.W.; Roberts, C. Health care disparities and cervical cancer. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 2098–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, P.W.; Hall-Daniels, L.; Baker, S.; Perez, C.A. Comparison of clinical outcome in black and white women treated with radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 79, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A.; Chen, Y.T.; Concato, J. Differences in cervical cancer mortality among black and white women. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 94, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.J.; Given, C.W.; Roberts, C. Disparities in cancer diagnosis and survival. Cancer 2001, 91, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference on Cervical Cancer, Bethesda, Maryland, 1–3 April 1996. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 1996, 21, 1–148.

- Marquardt, K.; Büttner, H.H.; Broschewitz, U.; Barten, M.; Schneider, V. Persistent carcinoma in cervical cancer screening: Non-participation is the most significant cause. Acta Cytol. 2011, 55, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, A.B.; Rebolj, M.; Habbema, J.D.; van Ballegooijen, M. Nonattendance is still the main limitation for the effectiveness of screening for cervical cancer in the Netherlands. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 2372–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. About Cervical Cancer: Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer. 2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Winer, R.L.; Lin, J.; Tiro, J.A.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Beatty, T.; Gao, H.; Kimbel, K.; Thayer, C.; Buist, D.S.M. Effect of Mailed Human Papillomavirus Test Kits vs Usual Care Reminders on Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake, Precancer Detection, and Treatment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1914729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyden, W.A.; Manos, M.M.; Geiger, A.M.; Weinmann, S.; Mouchawar, J.; Bischoff, K.; Yood, M.U.; Gilbert, J.; Taplin, S.H. Cervical Cancer in Women With Comprehensive Health Care Access: Attributable Factors in the Screening Process. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement. Cervical Cancer: Screening. 2018. Available online: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/cervical-cancer-screening2 (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Trends Progress Report: Cervical Cancer Screening. April 2022. Available online: https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/cervical_cancer#:~:text=In%202019%2C%2073.5%25%20of%20women,date%20with%20cervical%20cancer%20screening (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Sahasrabuddhe, V. NCI Cervical Cancer ‘Last Mile’ Initiative. 2022. Available online: https://prevention.cancer.gov/lastmile (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Texas Cancer Registry Texas Department of State Health Services. Cervical Cancer in Texas. 2019. Available online: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/tcr/data/cervical-cancer.aspx?terms=Cervical%20Cancer%20in%20Texas (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Benard, V.B.; Thomas, C.C.; King, J.; Massetti, G.M.; Doria-Rose, V.P.; Saraiya, M. Vital signs: Cervical cancer incidence, mortality, and screening-United States, 2007–2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akinlotan, M.; Bolin, J.N.; Helduser, J.; Ojinnaka, C.; Lichorad, A.; McClellan, D. Cervical Cancer Screening Barriers and Risk Factor Knowledge Among Uninsured Women. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asare, M.; Lanning, B.A.; Isada, S.; Rose, T.; Mamudu, H.M. Feasibility of Utilizing Social Media to Promote HPV Self-Collected Sampling among Medically Underserved Women in a Rural Southern City in the United States (US). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute (n.d). State Cancer Profiles. Screening and Risk Factors Table. Available online: https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/risk/index.php?topic=women&risk=v17&race=00&type=risk&sortVariableName=default&sortOrder=default#results (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Coronado, G.D.; Thompson, B.; Koepsell, T.D.; Schwartz, S.M.; McLerran, D. Use of Pap test among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites in a rural setting. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Carmen, M.G.; Findley, M.; Muzikansky, A.; Roche, M.; Verrill, C.L.; Horowitz, N.; Seiden, M.V. Demographic, risk factor, and knowledge differences between Latinas and non-Latinas referred to colposcopy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 104, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindau, S.T.; Tomori, C.; Lyons, T.; Langseth, L.; Bennett, C.L.; Garcia, P. The association of health literacy with cervical cancer prevention knowledge and health behaviors in a multiethnic cohort of women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A.; Gregoire, L.; Pilarski, R.; Zarbo, A.; Gaba, A.; Lancaster, W.D. Human papillomavirus, cervical cancer and women’s knowledge. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2008, 32, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, L.; Joseph, N.; Velazquez, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Munro, E.; Muzikansky, A.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Del Carmen, M.G. Understanding barriers to cervical cancer screening among Hispanic women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 199.e1–199.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Kessler, C.L.; Mori, N.; Chauhan, S.P. Cervical cancer screening in the United States, 1993-2010: Characteristics of women who are never screened. J. Women’s Health 2012, 21, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Palmer, C.; Bik, E.M.; Cardenas, J.P.; Nunez, H.; Kraal, L.; Bird, S.W.; Bowers, J.; Smith, A.; Walton, N.A.; et al. Self-Sampling for Human Papillomavirus Testing: Increased Cervical Cancer Screening Participation and Incorporation in International Screening Programs. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, A.; Kulasingam, S.L.; Baer, A.; Hughes, J.P.; Myers, E.R.; Mao, C.; Kiviat, N.B.; Koutsky, L.A. Accuracy and cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening by high-risk HPV DNA testing of self-collected vaginal samples. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2010, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, F.; Mullins, R.; English, D.R.; Simpson, J.A.; Drennan, K.T.; Heley, S.; Wrede, C.D.; Brotherton, J.M.; Saville, M.; Gertig, D.M. Women’s experience with home-based self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.J.; Maynard, B.R.; Loux, T.; Fatla, J.; Gordon, R.; Arnold, L.D. The acceptability of self-sampled screening for HPV DNA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2017, 93, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehbe, I.; Wakewich, P.; King, A.D.; Morrisseau, K.; Tuck, C. Self-administered versus provider-directed sampling in the Anishinaabek Cervical Cancer Screening Study (ACCSS): A qualitative investigation with Canadian First Nations women. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Verdoodt, F.; Snijders, P.J.; Verhoef, V.M.; Suonio, E.; Dillner, L.; Minozzi, S.; Bellisario, C.; Banzi, R.; Zhao, F.H.; et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: A meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petignat, P.; Faltin, D.L.; Bruchim, I.; Tramer, M.R.; Franco, E.L.; Coutlee, F. Are self-collected samples comparable to physician-collected cervical specimens for human papillomavirus DNA testing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: Updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018, 363, k4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Castle, P.E.; Schiffman, M.; Wentzensen, N.; Heckman-Stoddard, B.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.V. Meta-analysis of agreement/concordance statistics in studies comparing self-vs clinician-collected samples for HPV testing in cervical cancer screening. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- President Cancer Panel. Closing Gaps in Cancer Screening: Connecting People, Communities, and Systems to Improve Equity and Access. February 2022. Available online: https://prescancerpanel.cancer.gov/report/cancerscreening/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Padela, A.I.; Malik, S.; Vu, M.; Quinn, M.; Peek, M. Developing religiously-tailored health messages for behavioral change: Introducing the reframe, reprioritize, and reform (“3R”) model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 204, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asare, M.; Agyei-Baffour, P.; Koranteng, A.; Commeh, M.E.; Fosu, E.S.; Elizondo, A.; Sturdivant, R.X. Assessing the Efficacy of the 3R (Reframe, Reprioritize, and Reform) Communication Model to Increase HPV Vaccinations Acceptance in Ghana: Community-Based Intervention. Vaccines 2023, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.J.; Salovey, P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.J.; Bartels, R.D.; Wlaschin, J.; Salovey, P. The strategic use of gain-and loss-framed messages to promote healthy behavior: How theory can inform practice. J. Commun. 2006, 56, S202–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, M.; Lanning, B.A.; Montealegre, J.R.; Akowuah, E.; Adunlin, G.; Rose, T. Determinants of Low-Income Women’s Participation in Self-Collected Samples for Cervical Cancer Detection: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Community Health Equity Res. Policy 2022, 0272684X221090060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Ntroduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R.; Bernard, H.R. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 70, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Sitaresmi, M.N.; Rozanti, N.M.; Simangunsong, L.B.; Wahab, A. Improvement of Parent’s awareness, knowledge, perception, and acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination after a structured-educational intervention. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, M.; Abah, E.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Lowenstein, L.; Lanning, B. HPV Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening among Women Living with HIV in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: What Do We Know and What Can Be Done? Healthcare 2022, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierz, A.J.; Ajeh, R.; Fuhngwa, N.; Nasah, J.; Dzudie, A.; Nkeng, R.; Anastos, K.M.; Castle, P.E.; Adedimeji, A. Acceptability of self-sampling for cervical cancer screening among women living with HIV and HIV-negative women in Limbé, Cameroon. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Age range 30–65; Mean (SD) = 48.57 ± 11.02 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 23 | 27.71 |

| Black or African American | 30 | 36.14 |

| Hispanics | 24 | 28.92 |

| Other | 6 | 7.23 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Not married | 58 | 69.88 |

| Married | 25 | 30.12 |

| Education | ||

| Graduate degree or higher | 17 | 20.48 |

| Undergraduate | 14 | 16.87 |

| High School | 25 | 30.12 |

| Less than High School | 27 | 32.53 |

| Insurance | ||

| No | 30 | 36.14 |

| Yes | 53 | 63.86 |

| Employment | ||

| Not working | 48 | 57.83 |

| Working | 35 | 42.17 |

| Annual Income | ||

| <$20,000 | 64 | 77.11 |

| >$20,000 | 19 | 22.89 |

| Screening behavior | ||

| Did not screen | 21 | 25.30 |

| Screened | 62 | 74.70 |

| Screening outcomes | ||

| Incomplete | 8 | 12.90 |

| Negative | 47 | 75.58 |

| Positive | 7 | 11.29 |

| Acceptability | ||

| Not acceptable | 4 | 4.82 |

| Acceptable | 79 | 95.18 |

| Appropriateness | ||

| No appropriate | 4 | 4.82 |

| Appropriate | 79 | 95.18 |

| Feasibility | ||

| Not feasible | 0 | 0.00 |

| Feasible | 83 | 100.00 |

| Unadjusted OR (95%, CI) | Adjusted OR (95%, CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 30–40 | 1.47 (0.38–5.66) | 1.48 (0.42–5.24) |

| 41–50 | 2.2 (0.54–9.01) | 1.36 (0.36–5.14) |

| >50 | Ref (--) | Ref (--) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 3.82 (1.13–12.94 | 3.88 (1.11–13.59) |

| Not Married | Ref (--) | Ref (--) |

| Insurance | ||

| Yes | 1.08 (0.40–2.96) | 1.12 (0.39–3.23) |

| No | Ref (--) | Ref (--) |

| Employment | ||

| Working | 1.18 (0.45–3.11) | 1.08 (0.40–2.94) |

| Not working | Ref (--) | Ref (--) |

| Income | ||

| Yes | 0.86 0.26–2.82) | 0.96 (0.27–3.43) |

| No | Ref (--) | Ref (--) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Other | 0.93 (0.10–8.46) | 0.84 (0.12–5.96) |

| African American | 2.78 (0.78–9.85) | 0.16 (0.04–0.65) |

| Hispanic | 4.27 (1.01–18.11) | 0.12 (0.02–0.67) |

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref (--) | Ref (--) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high sch | 1.23 (0.24–6.45) | 1.35 (0.24–7.46) |

| High school | 0.32 (0.07–1.50) | 15.97 (2.90–88.04) |

| Undergraduate | 0.15 (0.03–0.85) | 4.39 (1.06–18.19) |

| Graduate | Ref (--) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asare, M.; Elizondo, A.; Dwumfour-Poku, M.; Mena, C.; Gutierrez, M.; Mamudu, H.M. Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior among Medically Underserved Women: Effectiveness of 3R Communication Model. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091323

Asare M, Elizondo A, Dwumfour-Poku M, Mena C, Gutierrez M, Mamudu HM. Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior among Medically Underserved Women: Effectiveness of 3R Communication Model. Healthcare. 2023; 11(9):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091323

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsare, Matthew, Anjelica Elizondo, Mina Dwumfour-Poku, Carlos Mena, Mariela Gutierrez, and Hadii M. Mamudu. 2023. "Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior among Medically Underserved Women: Effectiveness of 3R Communication Model" Healthcare 11, no. 9: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091323

APA StyleAsare, M., Elizondo, A., Dwumfour-Poku, M., Mena, C., Gutierrez, M., & Mamudu, H. M. (2023). Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior among Medically Underserved Women: Effectiveness of 3R Communication Model. Healthcare, 11(9), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091323