Systematic Review: HIV, Aging, and Housing—A North American Perspective, 2012–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions

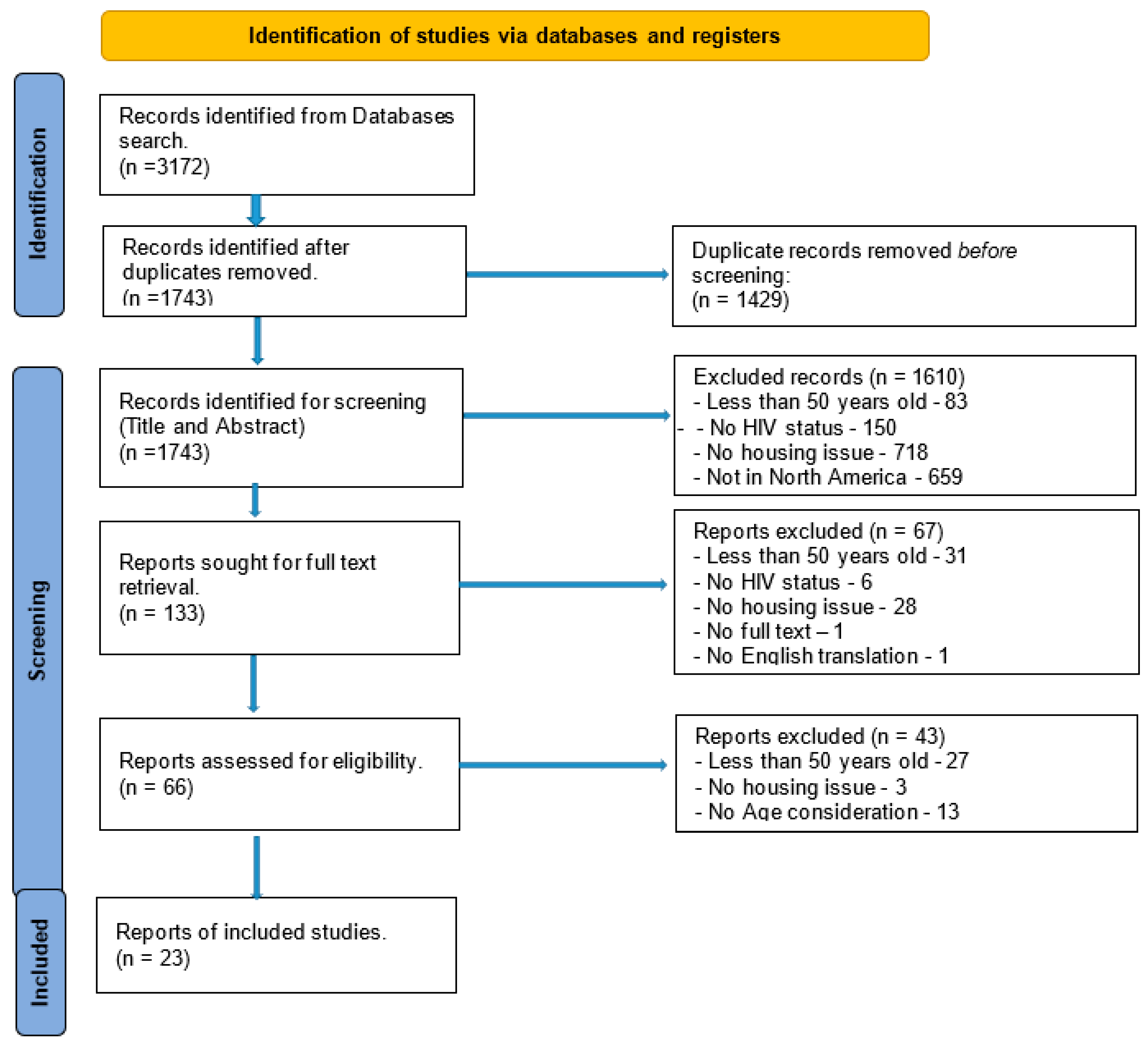

3. Methodology

4. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

| Search Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | |

| Search words/terms | HIV or AIDS or acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome or human immunodeficiency virus AND elderly or aged or older or elder or geriatric AND housing or (retirement home) or (nursing homes) or (care homes) or (long-term care) or (residential care) or (aged care facility). |

| Inclusion Criteria | Date of publication—January 2012–March 2023 (11 years) HIV diagnosis Language of publication—English, translation to English availability Type of articles includes full text/scholarly and peer-reviewed Study methodology—quantitative, qualitative (interviews, focus groups, ethnography), mixed-methods Geographic location(s) Country—North America (USA and Canada) Age of subjects > 50 yrs |

| Exclusion Criteria | Age of subjects < 50 yrs HIV status—negative Country—Not USA or Canada Abstract with an unavailable full article Language—not English/Translation not available Date of publication—(>10 yrs) Type of publication—letters, editorials, non-peer-reviewed articles, dissertations/theses, news and conference articles |

| Location | USA and Canada |

5. Results

| Systematic Review Characteristics of Included Studies: Summary | Study Design | Country | ||

| Author(s) | Date | Characteristics | ||

| Furlotte et al., 2012 [15] | Mar-12 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Sexuality, other—poverty, race | qualitative | Canada, Ottawa |

| Lane et al., 2013 [14] | Jan-13 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, other—Nurse caregiver impact, HIV/AIDS staff education | systematic lit. review | North America |

| Solomon et al., 2014 [17] | Feb-14 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, other—poverty, food and financial insecurity | qualitative | Canada, Ontario |

| Arnold et al., 2017 [18] | Jan-17 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—poverty, food and financial insecurity | qualitative | USA, San Francisco |

| Cox and Brennan-Ing, 2017 [19] | Jan-17 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—case management, clinical provider referrals, mental health, and substance use treatment, housing assistance, legal services, nutrition, transportation, home care | review/commentary | USA |

| Siou et al., 2017 [20] | May-17 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), other—basic HIV transmission education and awareness for LTC staff | qualitative and quantitative | Canada, Toronto |

| Tobin et al., 2018 [21] | Jan-18 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—financial insecurity, physical health, mental health, relationships with family (safe physical space for socializing and collaborating with their peers (sexual minority populations)) | quantitative | USA, Baltimore |

| Solomon et al., 2018 [22] | Apr-18 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Social and community support, Other—fulfilling gendered and family roles. Financial insecurity | qualitative | Canada |

| Sok et al., 2018 [23] | May-18 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, other—role cultural differences may play in long-term caregiving preferences and advance planning care. (food, clothing) | quantitative | Canada, Ontario |

| Nguyen et al., 2019 [24] | Feb-19 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support | quantitative | USA, Los Angeles & New Orleans |

| Baguso et al., 2019 [25] | Apr-19 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, other trans-gender hormonal use | quantitative | USA, San Francisco |

| Olivieri-Mui, 2019 [26] | May-19 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Social and community support, other—financial insecurity | commentary | USA |

| Justice and Akgün, 2019 [27] | Jul-19 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization | commentary | USA |

| Whittle et al., 2020 [28] | Jan-20 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, other financial insecurity, physical and mental health | qualitative | USA |

| Wainwright et al., 2020 [29] | Jun-20 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, | quantitative | USA, DC |

| Yoo-Jeong et al., 2020 [30] | Jul-20 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Social and community support, other—trauma, financial insecurities, loneliness, social exclusion | quantitative | USA, Georgia, ATL |

| Chayama et al., 2020 [31] | Aug-20 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, other—Drug abuse | commentary | USA |

| Koehn et al., 2021 [32] | Jan-21 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—finacial insecurity | quantitative | Canada |

| Cherry et al., 2021 [33] | Jun-21 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—financial insecurity, provider competency, isolation/loneliness | qualitative | USA, Los Angeles |

| Murzin et al., 2022 [34] | Sep-22 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—Trauma, uncertainty, and alternative is to access support to age in place, at home, but this option is also fraught with barriers | qualitative | Canada, Ontario |

| Vorobyova et al., 2022 [35] | Oct-22 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other | qualitative | Canada |

| Mitchell et al., 2023 [36] | Feb-23 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—health comorbidities, economic, food, and job insecurity, lack of transportation | qualitative—mixed method design | USA |

| Weinstein et al., 2023 [37] | Mar-23 | Aging/Elderly housing options, Stigma (HIV-related, sexuality, race), Housing-related HIV health outcomes/healthcare utilization, Sexuality, Social and community support, Other—illicit substance use, and depression. financial hardship due to HIV-related disability, and social isolation related to decades of marriage inequality). | quantitative | USA, Florida |

6. Quality of Included Studies and Risk of Bias Assessment

7. Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA)

8. Discussion

9. Topic Extraction

10. Discussion

11. Strengths and Limitations

12. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. OHCHR|The Human Right to Adequate Housing. OHCHR. 2022. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-housing/human-right-adequate-housing (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Aidala, A.A.; Wilson, M.G.; Shubert, V.; Gogolishvili, D.; Globerman, J.; Rueda, S.; Bozack, A.K.; Caban, M.; Rourke, S.B. Housing Status, Medical Care, and Health Outcomes Among People Living With HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, e1–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-26-1.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Wing, E.J. The Aging Population with HIV Infection. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2017, 128, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States and Dependent Areas. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Yasin, F.; Rizk, C.; Taylor, B.; Barakat, L.A. Substantial gap in primary care: Older adults with HIV presenting late to care. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourcher, V.; Gourmelen, J.; Bureau, I.; Bouee, S. Comorbidities in people living with HIV: An epidemiologic and economic analysis using a claims database in France. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, J.L.; Leyden, W.A.; Alexeeff, S.E.; Anderson, A.N.; Hechter, R.C.; Hu, H.; Lam, J.O.; Towner, W.J.; Yuan, Q.; Horberg, M.A.; et al. Comparison of Overall and Comorbidity-Free Life Expectancy Between Insured Adults with and without HIV Infection, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e207954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, T.; Sugrue, D.; Hayward, O.; McEwan, P.; Anderson, S.-J.; Lopes, S.; Punekar, Y.; Oglesby, A. Estimating HIV Management and Comorbidity Costs Among Aging HIV Patients in the United States: A Systematic Review. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2020, 26, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewes, J.; Ebert, J.; Langer, P.C.; Kleiber, D.; Gusy, B. Social inequalities in health-related quality of life among people aging with HIV/AIDS: The role of comorbidities and disease severity. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, T.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, D.; Dragovic, G.; Vasylyev, M.; Saumoy, M.; Blanco, J.R.; García, D.; Koval, T.; Loste, C.; Westerhof, T.; et al. Identifying the needs of older people living with HIV (≥50 years old) from multiple centres over the world: A descriptive analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2023, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walmsley, S.L.; Ren, M.; Simon, C.; Clarke, R.; Szadkowski, L. Pilot study assessing the Rotterdam Healthy Aging Score in a cohort of HIV-positive adults in Toronto, Canada. AIDS 2020, 34, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Conde, M.; Díaz-Alvarez, J.; Dronda, F.; Brañas, F. Why are people with HIV considered “older adults” in their fifties? Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 10, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.; Hirst, S.; Reed, M. Housing Options for North American Older Adults with HIV/AIDS. Indian J. Gerontol. 2013, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Furlotte, C.; Schwartz, K.; Koornstra, J.J.; Naster, R. “Got a room for me?” Housing Experiences of Older Adults Living with HIV/AIDS in Ottawa. Can. J. Aging/Rev. Can. Vieil. 2012, 31, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, P.; O’Brien, K.; Wilkins, S.; Gervais, N. Aging with HIV and disability: The role of uncertainty. AIDS Care 2013, 26, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, E.A.; Weeks, J.; Benjamin, M.; Stewart, W.R.; Pollack, L.M.; Kegeles, S.M.; Operario, D. Identifying social and economic barriers to regular care and treatment for Black men who have sex with men and women (BMSMW) and who are living with HIV: A qualitative study from the Bruthas cohort. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, L.E.; Brennan-Ing, M. Medical, Social and Supportive Services for Older Adults with HIV. HIV Aging 2017, 42, 204–221. [Google Scholar]

- Siou, K.; Mahan, M.; Cartagena, R.; Carusone, S.C. A growing need—HIV education in long-term care. Geriatr. Nurs. 2017, 38, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, K.E.; Winiker, A.K.; Smith, C. Understanding the Needs of Older (Mature) Black Men who have Sex with Men: Results of a Community-based Survey. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, P.; O’brien, K.K.; Nixon, S.; Letts, L.; Baxter, L.; Gervais, N. Qualitative longitudinal study of episodic disability experiences of older women living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, P.; Gardner, S.; Bekele, T.; Globerman, J.; Seeman, M.V.; Greene, S.; Sobota, M.; Koornstra, J.J.; Monette, L.; Hambly, K.; et al. Unmet basic needs negatively affect health-related quality of life in people aging with HIV: Results from the Positive Spaces, Healthy Places study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Manolova, G.; Daskalopoulou, C.; Vitoratou, S.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 2019, 9, 2235042X19870934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baguso, G.N.; Turner, C.M.; Santos, G.; Raymond, H.F.; Dawson-Rose, C.; Lin, J.; Wilson, E.C. Successes and final challenges along the HIV care continuum with transwomen in San Francisco. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri-Mui, B.L. Access to HIV Medication in the Community Versus a Nursing Home for the Medicare Eligible HIV population. Del. J. Public Health 2019, 5, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, A.C.; Akgün, K.M. What does aging with HIV mean for nursing homes? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1327–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H.; Leddy, A.; Shieh, J.; Tien, P.; Ofotokun, I.; Adimora, A.; Turan, J.M.; Frongillo, E.A.; Turan, B.; Weiser, S.D. Precarity and health: Theorizing the intersection of multiple material-need insecurities, stigma, and illness among women in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, J.J.; Beer, L.; Tie, Y.; Fagan, J.L.; Dean, H.D. Socioeconomic, Behavioral, and Clinical Characteristics of Persons Living with HIV Who Experience Homelessness in the United States, 2015–2016. AIDS Behav. 2019, 24, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo-Jeong, M.; Hepburn, K.; Holstad, M.; Haardörfer, R.; Waldrop-Valverde, D. Correlates of loneliness in older persons living with HIV. AIDS Care 2019, 32, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayama, K.L.; Ng, C.; McNeil, R. Addressing treatment and care needs of older adults living with HIV who use drugs. Afr. J. Reprod. Gynaecol. Endosc. 2020, 23, e25577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, K.; Burgess, H.; Lyndon, S.; Lu, M.; Ye, M.; Hogg, R.S.; Parashar, S.; Barrios, R.; Salters, K.A. Characteristics of older adults living with HIV accessing home and community care services in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS Care 2021, 33, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, S.T.; Tyagi, K.; Bailey, J.; Reagan, B.; Jacuinde, V.; Soto, J.; Klinger, I.; Mutchler, M.G. More to come: Perspectives and lived experiences of adults aging with HIV. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2021, 34, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzin, K.; Racz, E.; Behrens, D.M.; Conway, T.; Da Silva, G.; Fitzpatrick, E.; Lindsay, J.D.; Walmsley, S.L.; PANACHE Study Team. “We can hardly even do it nowadays. So, what’s going to happen in 5 years from now, 10 years from now?” The health and community care and support needs and preferences of older people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada: A qualitative study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e25978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyova, A.; Van Tuyl, R.; Cardinal, C.; Marante, A.; Magagula, P.; Lyndon, S.; Parashar, S. Obstacles and Pathways on the Journey to Access Home and Community Care by Older Adults Living With HIV/AIDS in British Columbia, Canada: Thrive, a Community-Based Research Study. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2023, 35, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.D.; Utterback, L.; Hibbeler, P.; Logsdon, A.R.; Smith, P.F.; Harris, L.M.; Castle, B.; Kerr, J.; Crawford, T.N. Patient-Identified Markers of Quality Care: Improving HIV Service Delivery for Older African Americans. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, E.R.; Lozano, A.; Jones, M.A.; Jimenez, D.E.; Safren, S.A. Factors Associated with Anti-retroviral Therapy Adherence Among a Community-Based Sample of Sexual Minority Older Adults with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 3285–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landauer, T.K.; Dumais, S.T. A solution to Plato’s problem: The latent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychol. Rev. 1997, 104, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehra, S.S.; Singh, J.; Rai, H.S. Using Latent Semantic Analysis to Identify Research Trends in OpenStreetMap. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengiste, S.A.; Antypas, K.; Johannessen, M.R.; Klein, J.; Kazemi, G. eHealth policy framework in Low and Lower Middle-Income Countries; a PRISMA systematic review and analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arachchige, I.A.N.; Sandanapitchai, P.; Weerasinghe, R. Investigating Machine Learning & Natural Language Processing Techniques Applied for Predicting Depression Disorder from Online Support Forums: A Systematic Literature Review. Information 2021, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yendewa, G.A.; Poveda, E.; Yendewa, S.A.; Sahr, F.; Quiñones-Mateu, M.E.; Salata, R.A. HIV/AIDS in Sierra Leone: Characterizing the Hidden Epidemic. Aids Rev. 2019, 20, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, M.; Wolton, A.; Crenna-Jennings, W.; Benton, L.; Kirwan, P.; Lut, I.; Okala, S.; Ross, M.; Furegato, M.; Nambiar, K.; et al. Experiences of stigma and discrimination in social and healthcare settings among trans people living with HIV in the U.K. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Grosse, A.; Zhabokritsky, A.; Sirisegaram, L. Understanding geriatric models of care for older adults living with HIV: A scoping review and qualitative analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, H.M.; Shaffer, P.M.; Nelson, S.E.; Shaffer, H.J. Changing Social Networks Among Homeless Individuals: A Prospective Evaluation of a Job- and Life-Skills Training Program. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 52, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan-Ing, M. Diversity, stigma, and social integration among older adults with HIV. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 10, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Ren, J.; Luo, Y.; Watson, R.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, L.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y. Preference for care models among older people living with HIV: Cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, G.; Plankey, M.W. Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Among People Living with HIV while Experiencing Homelessness. Georget. Med. Rev. 2023, 7, 90758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term ID | Term | Frequency | Number of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HIV | 94 | 23 |

| 2 | live | 27 | 19 |

| 3 | old | 51 | 18 |

| 4 | health | 34 | 16 |

| 5 | care | 60 | 14 |

| 6 | adult | 19 | 12 |

| 7 | study | 14 | 12 |

| 8 | age | 20 | 11 |

| 9 | older adult | 18 | 11 |

| 10 | experience | 12 | 10 |

| 11 | year | 13 | 10 |

| 12 | research | 13 | 10 |

| 13 | social | 18 | 10 |

| 14 | stigma | 15 | 10 |

| 15 | age | 16 | 9 |

| 16 | barrier | 17 | 9 |

| 17 | experience | 15 | 9 |

| 18 | finding | 10 | 9 |

| 19 | house | 13 | 9 |

| 20 | participant | 15 | 9 |

| Cluster ID | Cluster Name | Cluster Description | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Improvements to access to housing and healthcare services and policy formulation | +increase + associate + improve + policy + home + adult + ‘older adult’ + barrier care + service aids + explore research + finding + study | 16 | 70% |

| 2 | Unmet needs—social support, mental health, finance, food, and sexuality insecurities. | +woman + conduct + man + theme mental + uncertainty basic financial food qualitative social + interview + provider approach + include | 7 | 30% |

| Gategory | Topic ID | Document Cutoff | Term Cutoff | Topic | Number of Terms | Number of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple | 1 | 0.001 | 0.13 | +service, +service, treatment, +include, care | 17 | 21 |

| Multiple | 2 | 0.001 | 0.13 | +uncertainty, +woman, +man, food, basic | 17 | 20 |

| Multiple | 3 | 0.001 | 0.129 | PLWH, home, +home, art, access | 10 | 15 |

| Multiple | 4 | 0.001 | 0.13 | homelessness, HIV-related, +outcome, +associate, care | 20 | 19 |

| Topic ID | Topic | Theme | Number of Terms | Number of Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | +service, +service, treatment, +include, care | Holistic Care Approach elements | 17 | 21 |

| 2 | +uncertainty, +woman, +man, food, basic | Insecurities—Food, financial, sexuality, and other basic needs | 17 | 20 |

| 3 | PLWH, home, +home, art, access | Access to housing and treatment/care | 10 | 15 |

| 4 | homelessness, HIV-related, +outcome, +associate, care | Homelessness and HIV-related health outcomes | 20 | 19 |

| Cluster ID | Cluster Name | Topic ID; Terms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Improvements to access to housing and healthcare services and policy formulation | Topic 1; +service, +service, treatment, +include, care Topic 3; PLWH, home, +home, art, access Topic 4; homelessness, HIV-related, +outcome, +associate, care |

| 2 | Unmet needs—social support, mental health, finance, food, and sexuality insecurities. | Topic 2; +uncertainty, +woman, +man, food, basic |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvements to access to housing and healthcare services and policy formulation | Unmet needs—social support, mental health, and finance and food insecurities. | |||||

| # | Author | Date | Topic 1. +service, treatment, +include, care | Topic 3; PLWH, home, +home, art, access | Topic 4; homelessness, HIV-related, +outcome, +associate, care | Topic 2; +uncertainty, +woman, +man, food, basic |

| 1 | Furlotte et al., 2012 [15] | Mar-12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Lane et al., 2013 [14] | Jan-13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | Solomon et al., 2014 [17] | Feb-14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Arnold et al., 2017 [18] | Jan-17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | Cox and Brennan-Ing, 2017 [19] | Jan-17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | Siou et al., 2017 [20] | May-17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | Tobin et al., 2018 [21] | Jan-18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | Solomon et al., 2018 [22] | Apr-18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | Sok et al., 2018 [23] | May-18 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | Nguyen et al., 2019 [24] | Feb-19 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | Baguso et al., 2019 [25] | Apr-19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | Olivieri-Mui, 2019 [26] | May-19 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 13 | Justice and Akgün, 2019 [27] | Jul-19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | Whittle et al., 2020 [28] | Jan-20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 15 | Wainwright et al., 2020 [29] | Jun-20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | Yoo-Jeong et al., 2020 [30] | Jul-20 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 17 | Chayama et al., 2020 [31] | Aug-20 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | Koehn et al., 2021 [32] | Jan-21 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 19 | Cherry et al., 2021 [33] | Jun-21 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 20 | Murzin et al., 2022 [34] | Sep-22 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 21 | Vorobyova et al., 2022 [35] | Oct-22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | Mitchell et al., 2023 [36] | Feb-23 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 23 | Weinstein et al., 2023 [37] | Mar-23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 15 | 19 | 20 | ||

| Frequency % | 91 | 65 | 83 | 87 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaminuka, A.S.; Prybutok, G.; Prybutok, V.R.; Senn, W.D. Systematic Review: HIV, Aging, and Housing—A North American Perspective, 2012–2023. Healthcare 2024, 12, 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12100992

Chaminuka AS, Prybutok G, Prybutok VR, Senn WD. Systematic Review: HIV, Aging, and Housing—A North American Perspective, 2012–2023. Healthcare. 2024; 12(10):992. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12100992

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaminuka, Arthur S., Gayle Prybutok, Victor R. Prybutok, and William D. Senn. 2024. "Systematic Review: HIV, Aging, and Housing—A North American Perspective, 2012–2023" Healthcare 12, no. 10: 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12100992

APA StyleChaminuka, A. S., Prybutok, G., Prybutok, V. R., & Senn, W. D. (2024). Systematic Review: HIV, Aging, and Housing—A North American Perspective, 2012–2023. Healthcare, 12(10), 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12100992