Abstract

Background: Twenty years after the “To Err Is Human” report, one in ten patients still suffer harm in hospitals in high-income countries, highlighting the need to strengthen the culture of safety in healthcare. This scoping review aims to map patient safety culture strengthening strategies described in the literature. Method: This scoping review follows the JBI methodology. It adhered to all scoping review checklist items (PRISMA-ScR) with searches in the Lilacs, MedLine, IBECS, and PubMed databases and on the official websites of Brazilian and North American patient safety organizations. The research took place during the year 2023. Results: In total, 58 studies comprising 52 articles and 6 documents from health organizations were included. Various strategies were identified and grouped into seven categories based on similarity, highlighting the need for a comprehensive organizational approach to improve patient care. The most described strategies were communication (69%), followed by teamwork (58.6%) and active leadership (56.9%). Conclusion: The identified strategies can promote the development of a culture in which an organization can achieve patient safety, involving practices and attitudes that reduce risks and errors in healthcare. However, the identification of strategies is limited because it is restricted to certain databases and websites of international organizations and does not cover a broader spectrum of sources. Furthermore, the effectiveness of these strategies in improving patient safety culture has not yet been evaluated.

1. Introduction

The updated definition of patient safety by the World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the importance of adopting preventative measures to consistently reduce risks and prevent harm, as well as minimize the consequences of that harm when it occurs. This definition highlights the need for a proactive and systematic approach to safety in healthcare [1]. The relevance of this issue is further highlighted when considering the Institute of Medicine’s landmark report from 2000, entitled “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System”. This report was a landmark, raising awareness of the severity of errors and ushering in a new era of focus on patient safety as an essential component of quality healthcare [2,3]. Despite significant progress since the publication of this report, challenges persist. Some two decades later, it is still estimated that approximately one in ten patients in high-income countries suffer some type of harm while receiving hospital care. This statistic underscores the complexity of completely eradicating risks associated with healthcare and the importance of ongoing, effective strategies to improve patient safety, highlighting the need for a global, integrated approach to addressing these challenges. Therefore, patient safety remains a critical issue that requires continuous attention, research and implementation of best practices worldwide [2,3].

There is currently consensus in the literature on the need to support these initiatives to develop and improve patient safety culture to reduce the occurrence of incidents [4,5]. This culture encompasses attitudes, perceptions, values, individual and group competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine commitment, style, and proficiency regarding patient safety issues [4,5].

Therefore, health organizations worldwide advocate implementing practices and programs to strengthen patient safety culture. These strategies are used in experiences from high-reliability organizations, such as the nuclear and aviation industries, which involve high-risk operations but with few occurrences of events [6].

In this context, the objective of this scoping review is justified, which aims to map strategies for strengthening the patient safety culture described in the literature—a complex, multifaceted, and multidimensional topic that spans safety policies, healthcare professional training, and patient involvement, among other aspects. This review can provide valuable information for decision-making in healthcare services and patient safety policies, aiming to summarize the current state of knowledge and highlight promising strategies [7].

Furthermore, the novelty of this study lies in the compilation and analysis of contemporary and innovative strategies, which offers a unique contribution to the field of health security. This review adds value by consolidating practices and interventions that have not been widely discussed or integrated in previous reviews [7].

Strategies for strengthening patient safety culture refer to planned and targeted approaches to promote an organizational culture where safety is valued, incorporated, and practiced by all members of an organization. These strategies aim to create an environment in which safety is a priority and is integrated into daily processes, behaviors, and decisions [8,9,10,11].

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review followed the JBI methodology following the PRISMA-ScR Checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews): problem and research question formulation; data collection; data analysis and interpretation; data categorization; and presentation of results and conclusions [7].

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The protocol was developed and registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository in June 2023, available at: https://osf.io/edtc6/, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EDTC6 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The PCC strategy—an acronym for population (all health professionals, such as doctors, nurses, nursing assistants, among others), concept (strategies for strengthening the patient safety culture), and context (health services, such as primary healthcare, hospitals, and long-term care, among others)—was used to define the research question. The guiding question for this review was “What are the strategies for strengthening the patient safety culture in healthcare services described in the literature?” The review aimed to map the strategies for strengthening patient safety culture described in the literature.

A prior review was carried out on the OSF platform with the aim of identifying completed or ongoing review protocols on this topic, but no results were obtained.

Regarding the studies, those that addressed the guiding question were included, if they were without language restrictions, published in the last ten years, in full, freely available in journals accessible through the selected databases, and consistent with the proposed objective and with the descriptors listed in the search. Restricted-access databases can be accessed through computers at the Federal University of Paraná or via home connection through the CAFe Network and VPN/UFPR Remote Connection. Studies related to patient safety culture that did not describe strategies and/or tools for strengthening patient safety culture were excluded.

The inclusion criteria for documents from Brazilian and North American health organizations (patient safety organizations in these regions are leaders in innovation and safety policy development, which can provide valuable insights into best practices and emerging trends) were as follows: documents available on the researched websites, with content specifically focused on the proposed theme, in leading organizations or that influenced the thematic areas of the review, contributed to innovative research, policies, or practices and were relevant. The exclusion criteria comprised documents that did not describe strategies and/or tools for strengthening patient safety culture, including those related to patient safety but not those related to patient safety culture.

2.3. Search Strategy

The research was carried out in three stages. In the first stage, a search was carried out in the PubMed database to identify descriptors and keywords related to the topic. In the second stage, these were applied to the databases consulted, with due adaptation. The third phase consisted of analyzing the bibliographic references of the selected documents to retrieve potentially relevant documents.

In national and international publication databases, the search took place in November 2022, with study selection in the following databases: the Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (Lilacs), the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MedLine), the Spanish Bibliographic Index in Health Sciences (IBECS), and the National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health (PubMed). LILACS and IBECS specialize in the scientific literature from Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain. This choice ensured that the research included a regional perspective that may be less represented in other broader international databases, providing a more complete view of patient safety practices in these specific regions. The selection of these databases allows access to studies published in Spanish and Portuguese, the predominant languages in Latin America and Spain. This is crucial for capturing cultural and linguistic nuances that can influence patient safety practices and public health policies in these areas. The temporal cutoff was the last ten years to track the evolution of strategies used and identify the most recent and effective ones because patient safety is a field in constant evolution, with new research, discoveries, and practices emerging over time. Thus, it is convenient to identify and analyze the most current strategies that have been successfully implemented to strengthen patient safety culture. These strategies likely reflect current best practices and provide valuable insights for improving patient safety in the present and future.

The search strategy was developed with the assistance of a librarian (Table 1). MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) descriptors were used in four languages, Portuguese, English, Spanish, and French, along with Boolean operators represented by “AND” (restrictive combination) and/or “OR” (additive combination).

Table 1.

Search strategies with the use of descriptors, entry terms, and Boolean operators, according to the databases.

The search was conducted in November 2022 and updated in December 2023 on the Virtual Health Library (BVS) platform, applying filters from the following databases: Lilacs, MedLine, IBECS, and a search on PubMed.

In the search in PubMed, we did not insert any keywords relating to health services or health professionals because the search expression mainly used MesH descriptors, which are, by definition, specific to the health area, for example, the descriptor “organizational culture”, which is within the category “Organization and Administration” and is within the broader category “Health Services Administration”. The descriptor “safety management” belongs to the “risk management” category, which is also within the “Health Services Administration” category.

Searches on the official websites of patient safety organizations were conducted for organizations pioneering the topic of patient safety, including the World Alliance for Patient Safety (WAPS/WHO), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the National Steering Committee for Patient Safety (NSC), Joint Commission International (JCI), and the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), in addition to Brazilian organizations such as the Brazilian Institute for Patient Safety (IBSP), the Brazilian Society for Quality of Care and Patient Safety (SOBRASP), and the Patient Safety Foundation (FSP).

In healthcare organizations, the research period was between October and November 2022, with an update in December 2023, using the term “strategies for strengthening the patient safety culture” in the search field of the websites. Furthermore, document searches were initially conducted in Portuguese and later in English.

2.4. Study Selection

All articles were imported into Rayyan (a tool specifically developed to support the selection and inclusion of studies in reviews) for study selection based on titles and abstracts [12]. Two independent reviewers read and analyzed the data to identify those potentially eligible for the study, and a third independent reviewer resolved any conflicts of opinion.

To confirm the relevance of the research question, two reviewers read the selected studies in full.

2.5. Data Extraction

For data extraction, two Excel spreadsheets were created following the JBI data extraction model. The first comprised the following synthesis columns: title, author, year, language, and journal. The second synthesized the selected strategies, arranged in rows, while the columns represented the articles and organizations that were sources of these strategies.

To identify the strategies, the concept of an implementation strategy from the Taxonomy of Interventions in Health Systems of Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) was used, which defined implementation strategies as interventions designed to bring about changes in health organizations, the behavior of health professionals, or the use of health services by healthcare recipients [13].

This approach allowed for a clear and systematic organization of information, facilitating the analysis and understanding of the proposed strategies in each source. By structuring the strategies in a spreadsheet, it became easier to identify trends, similarities, and differences in the recommended strategies and proposed actions. Additionally, it provided an overview of the different perspectives and approaches adopted by various authors and organizations, contributing to a more comprehensive and informed analysis.

2.6. Evidence Analysis

For the analysis of the results and the final interpretation of the obtained data, the content analysis (CA) method proposed by Bardin was utilized [14].

Through preanalysis, superficial reading of all included articles and documents from databases and organizations was conducted to organize the selected material. Subsequently, there was an exploration of the material and data treatment, involving an exhaustive reading of the materials, breaking down the texts into categories due to the diversity of strategies found. This included identifying keywords for categorizing the strategies.

The selected strategies were listed and grouped based on similarities, such as training for leaders and team training grouped under the strategy of education/training system. The list of strategies was organized into two categories: (1) recommendations and (2) actions.

Recommendations in patient safety culture refer to guidelines based on evidence or expert consensus intended to guide practices, policies, or behaviors to promote patient safety within healthcare organizations. Actions refer to specific measures, strategies, or interventions implemented to meet the recommendations. These actions are practical and targeted and are designed to effect concrete changes to patient safety culture. They include implementing training programs for healthcare professionals on how to report and learn from errors, developing incident reporting systems that support open and nonpunitive communication, and promoting initiatives that strengthen management support for safe practices [15].

To construct groups of strategies based on their proximity, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied using R 4.2.2 software. This methodology allows the measurement of phenomena that are not directly observable, such as the importance of strategies according to the frequency with which they were used in the articles. PCA is used to identify latent constructs and aims to reduce the original information to a smaller set of factors, known as “loadings”. These loadings represent the latent dimensions (constructs) that summarize the original set of variables while maintaining the representativeness of the characteristics of the original variables [16].

In this study, PCA resulted in sets of loadings. This method constructs a cluster tree, also known as a “dendrogram”, in which objects are organized in hierarchical levels, reflecting their similarity to each other. Finally, grouping was performed based on the level of similarity among the located strategies, identifying groups of strategies that are more similar to each other at different levels of granularity.

3. Results

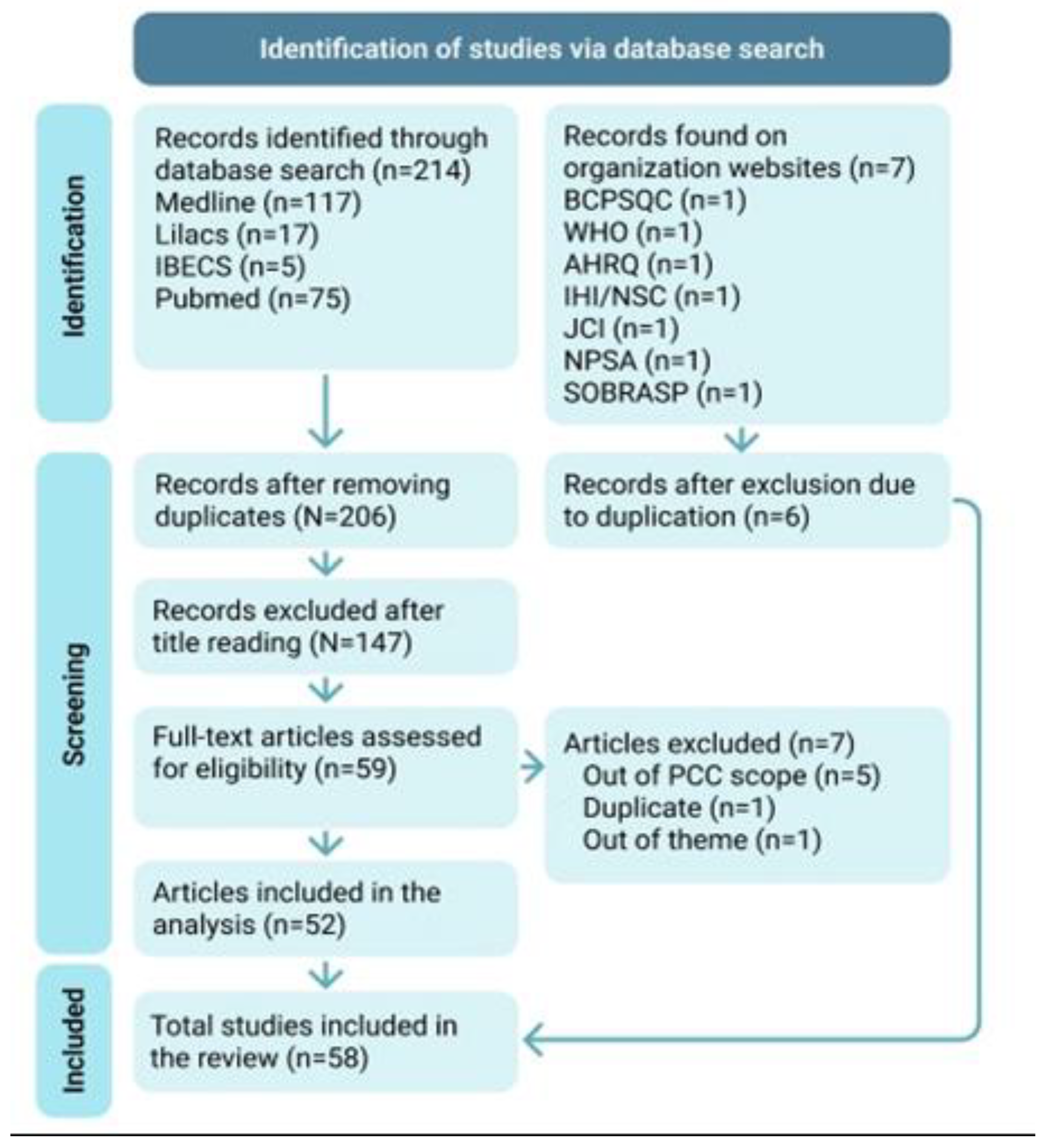

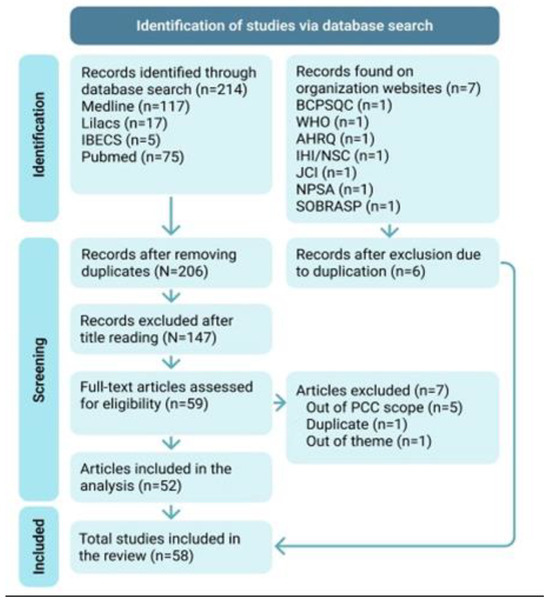

The search resulted in 139 articles in BVS (with 117 in MEDLINE, 17 in LILACS, and 5 in IBCS) and 75 articles in PubMed, totaling 214 articles. Of these, 8 duplicate articles were excluded. In the preselection phase, 129 articles were excluded based on title reading, and 20 had conflicting opinions. A third reviewer was invited for resolution, and 18 articles were excluded, leaving 59 articles for full-text reading.

After reading the complete texts, five articles that did not present any strategies for strengthening patient safety culture were excluded. One duplicated article that needed to be manually excluded after reading, as the duplicate was not identified in the preselection due to publication in two languages (English and Portuguese), and one article that did not address patient safety culture was excluded, for a total of 52 articles.

On the websites of healthcare organizations, seven documents addressing strategies for strengthening patient safety culture were found. The document from the BC Patient Safety & Quality Council (BCPSQC) was excluded as a duplicate, as it was translated into Portuguese on the SOBRASP website, totaling six documents.

Thus, 58 documents were included in the review for analysis and data extraction. No further documents were recovered through the analysis of bibliographic references.

Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the publication selection process included in this review.

Figure 1.

Modified PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for studies included within this scoping review. Subtitle: AHRQ—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; IBECS—Spanish Bibliographic Index in Health Sciences; IHI—Institute for Healthcare Improvement; JCI—Joint Commission International; Lilacs—Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; MedLine—Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; NSC—National Steering Committee for Patient Safety; NPSA—National Patient Safety Agency; PubMed—National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health; SOBRASP—Brazilian Society for Quality of Care and Patient Safety; WHO—World Health Organization.

Characteristics of the Studies

The 52 selected scientific articles were identified and labeled with the numbers 6 and 17 to 67 (Table 2), while the 6 documents from national and international patient safety organizations are listed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Identification of all selected articles in the review.

Table 3.

Documents from organizations selected for the review.

The studies were mostly published between 2015 and 2019, with the highest number occurring in 2017. English was the predominant language (48), followed by Portuguese (2), Spanish (1), and German (1). The main journals that published them were the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety (2), J. Healthc Risk Manag. (2), BMJ Open (2), The Journal of Nursing Administration (2), BMJ Quality & Safety (2), and J. Healthc Risk Manag. (2).

The results revealed 57 strategies, which were identified and categorized into 21 recommendations and 36 actions that are presented in Table 4, with their respective concepts and frequencies appearing in the documents.

Table 4.

Presentation of strategies mapped in the literature.

The most frequently mentioned strategies were related to communication (40), followed by teamwork (34) and active leadership (33). Regarding the frequency of strategies cited in each article, on average, each article mentioned approximately seven different strategies.

In the recommendations category, 21 strategies were listed in the 58 analyzed studies, with communication being the most prevalent at 69%, followed by teamwork at 58.6%, and active leadership at 56.9%.

In the actions category, 36 strategies were described, with 21 types of strategies having only one citation, corresponding to 1.72% each, meaning that 58.3% appeared in only one study. The most prevalent action strategy was team engagement at 20.6%, followed by meetings/group dynamics at 15.5% and realistic simulation at 13.7%.

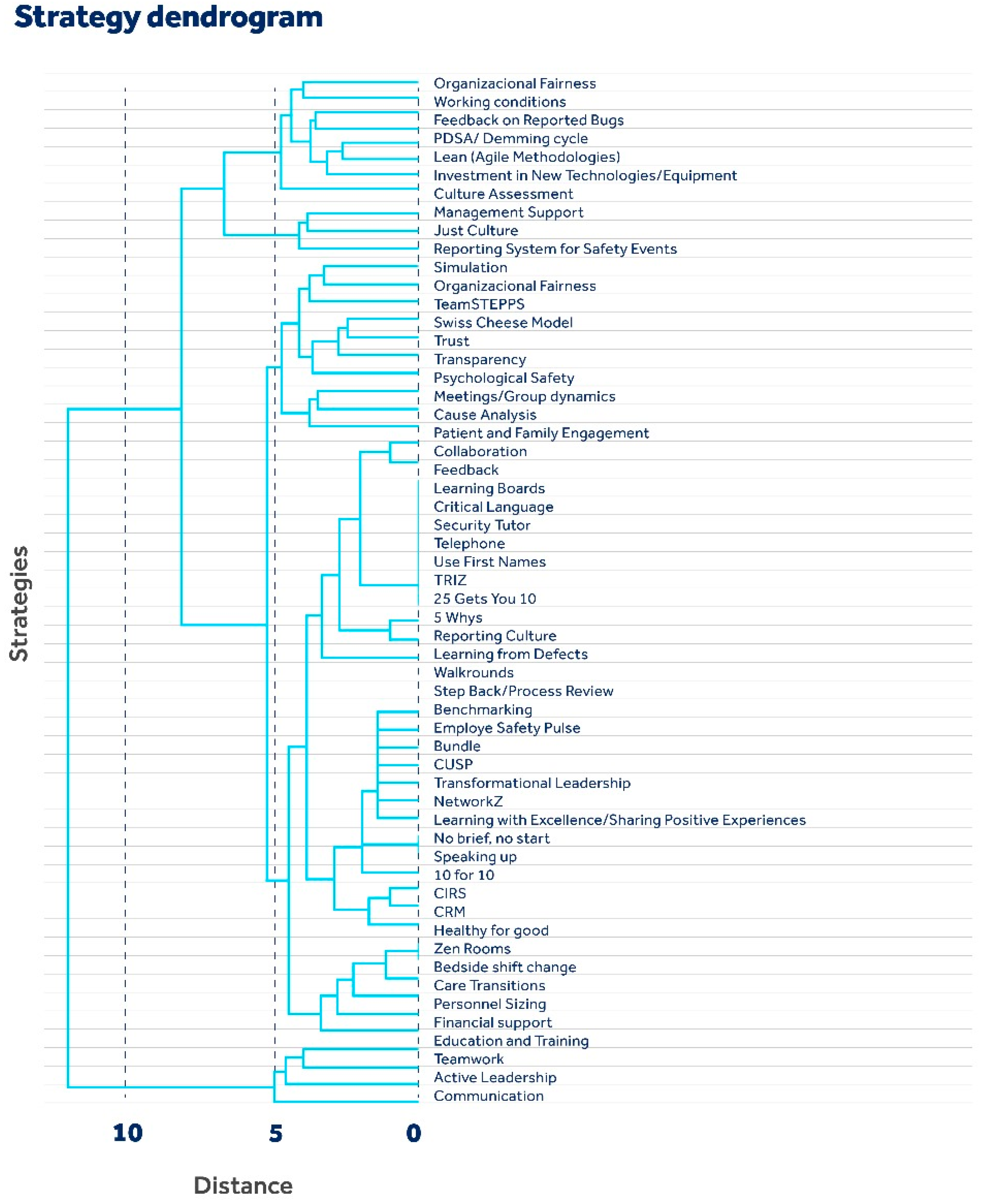

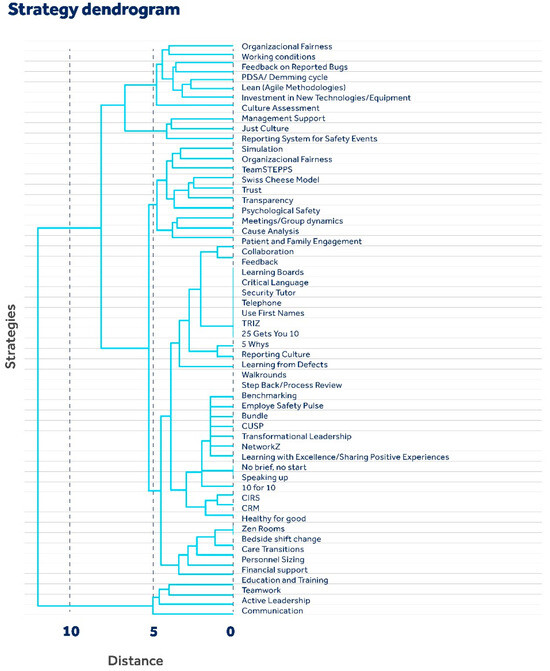

In the analysis to group the strategies based on their similarities, i.e., to determine how many articles they appear together in, the hierarchical dendrogram serves as a fundamental visual and analytical tool, as shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of strategies.

The dendrogram is a visual representation of the similarities between different strategies for strengthening safety culture. It is built using a hierarchical clustering algorithm, which groups strategies based on their similarities, forming a tree-like structure.

The horizontal axis (distance) represents the distance or dissimilarity between strategies. The greater the distance on the horizontal axis is, the less similar the strategies are. Vertical lines connect strategies at different levels of similarity. The vertical axis (strategies) lists the specific strategies that have been grouped. Each leaf of the dendrogram represents an individual strategy.

According to the dendrogram structure, strategies appearing together in many articles are linked by lower branches, indicating a strong relationship or a common pattern of strategy adoption within the studied field.

There are distinct levels of grouping visible, where some strategies are more closely related to each other than others. For example, “Trust”, “Transparency”, and “Psychological Safety” are grouped together at a low level of the dendrogram, which suggests that these strategies share greater similarity or are more often implemented together. Strategies that come together at the top of the dendrogram, such as “Bedside shift change” and “Care transitions”, indicate that although they share some similarity, they have significant differences compared to groups that come together more closely below.

Organizational protocols, feedback on reported errors, and patient and family engagement appear to be key strategies. These are fundamental to creating a culture in which patient safety is prioritized. The proximity of these strategies in the dendrogram suggests a strong interconnection between them.

The chart can also help determine which strategies could be adopted together or which could require different approaches. For example, when looking to improve communication within an organization, strategies that are close together on the dendrogram, such as “Telephone” and “Use First Names”, may be more effective when implemented together.

When analyzing the articles with the aim of grouping the strategies based on their similarities, that is, to determine how many articles they appear together, it is noted that articles 37 and 40 are directly connected. It is inferred that the strategies (teamwork, communication, active leadership, psychological safety, and educational systems) discussed in these articles have a high incidence of co-occurrence, suggesting that, in the literature, these strategies are often considered together or perhaps complement each other.

The strategies discussed in organization 1 (transparency, communication, active leadership, fair working conditions, and just culture) and in article 48 (teamwork, active leadership, shift transfer and transition issues, patient and family engagement, culture assessment, financial support, meetings/group dynamics, PDSA cycle, and bedside passage) occur at greater distances than most other pairs, which allows us to infer that there is a distinct relationship between patient safety strategies discussed in this article and those adopted or recommended by organization document 1.

Additionally, the presence of articles or documents from organizations such as organization 69 may indicate unique or new approaches to patient safety culture that are not widely discussed or have not yet been integrated into mainstream literature. This may point to emerging areas of research or innovative strategies that deserve additional attention.

Articles 46 and 57 show a strong positive correlation, suggesting that the strategies discussed are frequently mentioned or used together, both bringing to light communication strategies, fair culture, and notification systems. Articles 47 and 64 also mention common strategies.

The analysis of articles 18 and 33 suggested that the strategies discussed in these two articles are not strongly related or may even be inversely related.

A negative correlation may suggest that practices or strategies from one article are rarely implemented in conjunction with those from another or that the organizations’ approaches differ significantly.

Finally, in the grouping by the level of similarity between located strategies, seven groups were described, represented below:

Group 1: Organizational Principles and Culture: This group includes key principles such as organizational justice, transparency, trust, a Zen room, and just culture. These elements are fundamental to creating a healthy and ethical organizational culture. They establish the foundation for an environment where healthcare professionals can feel valued, respected, and confident in their ability to perform their duties. A just and transparent culture promotes accountability and reliability, which is crucial for patient safety.

Group 2: Leadership and Personal Development: Strong leadership is a central component of safety culture. This group addresses the development of leadership skills and the promotion of a learning culture in which professionals are encouraged to learn from their mistakes and report incidents openly and responsibly. This group includes the strategies security tutor, reporting culture, teamwork, learning from defects, active leadership, psychological safety, learning boards, working conditions, feedback, management support, NetworkZ, transformational leadership, and patient and family engagement.

Group 3: Education and Continuous Improvement: This group encompasses elements such as education/training systems, assessment of culture/strategies, cause analysis, feedback on reported bugs, organizational protocols, meetings/group dynamics, and speaking up. The continuous education of healthcare professionals is crucial for keeping them up-to-date and skilled. Culture assessment and root cause analysis help to identify problematic areas and opportunities for improvement. Feedback on errors allows learning from failures and implementing changes to avoid repeating mistakes in the future.

Group 4: Technology and Resources: Topics related to investments in technology and financial resources are included. The incorporation of new technologies and equipment can improve process efficiency and treatment accuracy. Adequate financial support is essential to ensure that the necessary resources are available to provide the best possible care to patients. The strategies included in this group are investment in new technologies/equipment, financial support, and reporting systems for safety events.

Group 5: Process improvement and safety: This group addresses specific tools and strategies to improve patient safety. Standardizing processes, identifying care transition issues, and implementing safety protocols are vital to minimizing errors and adverse events. Lean practices and other continuous improvement methodologies also help optimize processes and reduce waste. The following strategies are included: CRM, CIRS, simulation, staff sizing, care transitions, bedside handover, bundle, CUSP, step back and lean.

Group 6: Communication and Decision-Making: Effective communication is essential in all aspects of patient care. This group covers tools and techniques to improve communication, such as the use of first names and assertive communication techniques. These approaches help ensure that critical information is conveyed clearly and that decisions are made based on accurate data. This group includes communication, critical language, telephoning, using first names, TRIZ, 25 gets you 10, 5 whys, and collaboration.

Group 7: Improvement Strategies and Interventions: This group describes strategies and interventions that can be used to drive continuous improvement. This includes benchmarking, PDSA, and team involvement in the improvement process. There are also 10 respondents in this group: Walkrounds, TeamSTEPPS, the Swiss cheese model, Employee Safety Pulse, learning with excellence, and the health for good program. Such strategies provide a framework for identifying areas of opportunity and implementing effective changes.

4. Discussion

Patient safety culture refers to the organizational environment in a healthcare institution, where emphasis is placed on patient safety and well-being. An effective safety culture promotes a proactive approach to identifying, reporting, and preventing errors, adverse incidents, and adverse events, aiming to provide high-quality healthcare and minimize risks [73].

Therefore, culture is how we collaborate; collaboration is not just an activity but an expression of shared values, norms, and behaviors that define and are defined by the cultural environment in question [1]. Although it may seem challenging, the good news is that each of us, both individually and collectively, can promote it [68].

When we map strategies to strengthen patient safety culture, the objective of this review, we take an important step in improving healthcare safety. This involves the identification and categorization of practices and approaches that can be implemented to promote a strong safety culture. This is demonstrated in the study carried out in 2020 by Armutlu et al., in which a set of evidence-based practices was constructed that must be applied collectively to establish and maintain a culture of quality and safety in order to provide safe care [58].

In this research, scientific database searches and web-based activities tracked information relevant to the search results. Healthcare organizations and their publications on patient safety have been an enriching research environment, as they aim to contribute to improving healthcare decision-making based on the best available information, as we can see in the documents Culture Change Toolbox [68], Action Planning Tool for the AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture [69], Safer Together: A National Action Plan to Advance Patient Safety [70], Sentinel Event Alert 57: The essential role of leadership in developing a safety culture [71], The Incident Decision Tree: Guidelines for Action Following Patient Safety Incidents [72] and the Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030 [1].

Both research methods involved strategies targeting a diverse range of issues, including organizational principles, leadership, teamwork, continuous education, communication, and technologies. These areas are crucial for promoting a safe and collaborative environment in healthcare contexts. For example, effective communication is fundamental for avoiding errors, while teamwork and active leadership are essential for the efficient implementation of safety procedures and fostering a culture of shared responsibility and continuous learning.

Categorizing strategies into recommendations and actions is important for a future practical implementation approach. Recommendation strategies may include general principles or guidelines to enhance safety culture, while action strategies are specific practices that can be applied to achieve these objectives.

The correlation analyses carried out help to identify which strategies are commonly adopted together, which can be valuable for developing more integrated and comprehensive policies and training programs. For example, if strong leadership and effective communication are frequently correlated, focusing on both simultaneously may be an effective practice.

The fact that 21 strategies were mentioned only once, representing 58.3% of the total strategies appearing in only one study, suggests a wide range of specific or punctual approaches within the field, highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of patient safety culture and suggesting that these can be explored in future research.

The representativeness of the group with the seven strategic groups provided a comprehensive approach to improving patient care. Implementing these strategies may contribute to prioritizing patient safety across all areas of healthcare. This will help create an environment where healthcare professionals feel empowered to report issues, learn from past incidents, and take measures to prevent errors.

The strength of this review lies in the innovative analysis of the literature, citing important recommendations for strategies to improve patient safety culture. The identified strategies can promote the development of a culture in which an organization can achieve patient safety, involving practices and attitudes that reduce risks and errors in healthcare. This makes the study relevant and useful for health professionals and managers.

Limitations

This research was limited to identifying strategies and did not assess the effectiveness of these strategies in improving patient safety culture. Many studies in the literature present these strategies as recommendations, but their effectiveness in practice may vary.

Research is recommended to verify the effectiveness of the strategies listed in the literature in clinical practice. This suggests that research should not be limited to identifying strategies but should be accompanied by practical efforts to incorporate them into healthcare routines.

5. Final Considerations

The scoping review identified 57 strategies that can be used to support management in strengthening patient safety culture, involving practices and attitudes that reduce risks and errors in healthcare. This highlights the diversity of approaches available in the field of patient safety, indicating that there is no single or universally applicable approach, and healthcare organizations can choose from a wide range of strategies to meet their specific needs and the context in which they operate.

The strategies were divided into two main categories: recommendations and actions. In the recommendations group, 21 strategies were mentioned, with significant emphasis on those related to communication, teamwork, and active leadership. In the actions group, 36 strategies were listed, with a focus on team engagement, which reflects the importance of involving healthcare professionals in promoting patient safety, thereby encouraging active participation and commitment to safety practices.

The research results provide a valuable overview of current practices and have the potential to guide future research and practical implementations in the field of patient safety. This, in turn, can contribute to creating a safer and more efficient healthcare environment, benefiting both patients and healthcare professionals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.d.L.P. and K.C.F.; methodology, C.d.L.P. and K.C.F.; software, C.d.L.P.; validation, C.d.L.P., K.C.F., E.N., P.C. and P.L.; formal analysis, C.d.L.P. and K.C.F.; investigation, C.d.L.P.; resources, C.d.L.P., K.C.F., E.N., P.C. and P.L.; data curation, C.d.L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.d.L.P.; writing—review and editing, C.d.L.P., K.C.F., E.N., P.C. and P.L.; visualization, C.d.L.P., K.C.F., E.N., P.C. and P.L.; supervision, C.d.L.P., K.C.F., E.N., P.C. and P.L.; project administration, C.d.L.P., K.C.F., E.N., P.C. and P.L.; funding acquisition, E.N., P.C. and P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is funded by the Nursing Research, Innovation and Development Centre of Lisbon (CIDNUR), the Escola Superior de Enfermagem de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal (051/2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Patient Safety. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030: Toward Zero Patient Harm in Health Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; 108p. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.; Donaldson, M.S. (Eds.) Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. In To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System; Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, Health System: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; 312p. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Patient Safety. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/patient-safety (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Morello, R.T.; Lowthian, J.A.; Barker, A.L.; McGinnes, R.; Dunt, D.; Brand, C. Strategies for improving patient safety culture in hospitals: A systematic review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Surveillance Agency. Patient Safety Culture; Ministry of Health: Brasilia, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/servicosdesaude/seguranca-do-paciente/cultura-de-seguranca-do-paciente (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Lorenzini, E.; Oelke, N.D.; Marck, P.B.; Dall’agnol, C.M. Researching safety culture: Deliberative dialog with a restorative lens. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; pp. 406–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. The relationship between safety climate and safety performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health and Safety Executive-HSE. Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17; Crown: London, UK, 2016; 71p.

- Guldenmund, F.W. The nature of safety culture: A review of theory and research. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Thirty years of safety climate research: Reflections and future directions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy. 2015. Available online: https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições 70: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016; 230p. [Google Scholar]

- Liukka, M.; Hupli, M.; Turunen, H. Differences between professionals’ views on patient safety culture in long-term and acute care? A cross-sectional study. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2021, 34, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Análise Multivariada de Dados, 6th ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009; 688p. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, R.A. What interventionalists can learn from the aviation industry. Euro Interv. 2018, 13, 1977–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rall, M.; Oberfrank, S. Human factors und crisis resource management: Improving patient safety. Unfallchirurg 2013, 116, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabona, C.R.; Mora, A.U.; Callizo, E.P.; Cano, F.A.; Barbera, M.G.; Aristu, I.I.; Busto, C.S.; Astier-Peña, M.P. ¿Qué normativas han desarrollado las comunidades autónomas para avanzar en cultura de seguridad del paciente en sus organizaciones sanitarias? J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2019, 34, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyratsis, Y.; Ahmad, R.; Iwami, M.; Castro-Sánchez, E.; Atun, R.; Holmes, A.H. A multilevel neo-institutional analysis of infection prevention and control in English hospitals: Coerced safety culture change? Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 41, 1138–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, K.; Hochberg, E.; Cheng, J.J.; Lavette, L.B.; Merkeley, K.; Fahey, L.; Shah, R.K. Apparent Cause Analysis: A Safety Tool. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20191819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimenes, F.R.E.; Torrieri, M.C.G.R.; Gabriel, C.S.; Rocha, F.L.R.; Silva, A.E.B.D.C.; Shasanmi, R.O.; Cassiani, S.H.D.B. Applying an ecological restoration approach to study patient safety culture in an intensive care unit. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.W.; Silvera, G.A.; Kazley, A.S.; Diana, M.L.; Huerta, T.R. Assessing the relationship between patient safety culture and EHR strategy. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2016, 29, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.; Galla, C. Building a culture of safety through team training and engagement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, R. Building Safe, Highly Reliable Organizations: CQO Shares Words of Wisdom. Biomed. Instrum. Technol. 2017, 51, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, S.T.; Wang, D.D.; Rutledge, W.C.; Lau, D.; Berger, M.S.; Sankaran, S.; Lau, C.Y.; Imershein, S.G. Changing Operating Room Culture: Implementation of a Postoperative Debrief and Improved Safety Culture. World Neurosurg. 2017, 107, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, P.; Morgan, L.; New, S.; Catchpole, K.; Roberston, E.; Hadi, M.; Pickering, S.; Collins, G.; Griffin, D. Combining Systems and Teamwork Approaches to Enhance the Effectiveness of Safety Improvement Interventions in Surgery: The Safer Delivery of Surgical Services (S3) Program. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chera, B.S.; Mazur, L.; Adams, R.D.; Kim, H.J.; Milowsky, M.I.; Marks, L.B. Creating a Culture of Safety Within an Institution: Walking the Walk. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.F.B.; Lorenzini, E.; Schmidt, C.R.; Dal Pai, S.; Cavalheiro, K.A.; Kolankiewicz, A.C.B. Patient safety culture from the perspective of the multiprofessional team: An integrative review. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. Fundam. 2021, 13, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, J.L.; Hilligoss, B.; Knupp, A.; Bournique, J.; Sullivan, J.; Adkins, E.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.D. Cultural Transformation After Implementation of Crew Resource Management: Is It truly Possible? Am. J. Med. Qual. 2017, 32, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, B.D.; Roy, L.T. Developing a culture of safety in an imaging department. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2015, 12, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, P.; Linkson, L.; Evans, T.; Clausen, H.; Hothi, D. Developing person-centered analysis of harm in a pediatric hospital: A quality improvement report. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, S.L.; Fitzpatrick, J.J.; Siedlecki, S.L.; Dolansky, M.A. Employee Engagement and a Culture of Safety in the Intensive Care Unit. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 46, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flott, K.; Nelson, D.; Moorcroft, T.; Mayer, E.K.; Gage, W.; Redhead, J.; Darzi, A.W. Enhancing Safety Culture Through Improved Incident Reporting: A Case Study In Translational Research. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, F.T.L.D.S.; Callou, R.C.M.; Albuquerque, G.A.; Oliveira, R.M. Estratégias de comunicação efetiva no gerenciamento de comportamentos destrutivos e promoção da segurança do paciente. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2019, 40, e20180308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulibarrena, M.Á.; de Vicuña, L.S.; García-Alonso, I.; Lledo, P.; Gutiérrez, M.; Ulibarrena-García, A.; Echenagusia, V.; de la Parte, B.H. Evolution of Culture on Patient Safety in the Clinical Setting of a Spanish Mutual Insurance Company: Observational Study between 2009 and 2017 Based on AHRQ Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, L.; Shaw, L.; Jordan, J.E.; Alexander, M.; O’Brien, M.; Singer, S.J.; Manias, E. Factors Influencing the Implementation of a Hospital-wide Intervention to Promote Professionalism and Build a Safety Culture: A Qualitative Study. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2019, 45, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwappach, D.L.; Gehring, K. Withholding patient safety concerns. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 24, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshia, S.S.; Bryan Young, G.; Makhinson, M.; Smith, P.A.; Stobart, K.; Croskerry, P. Gating the holes in the Swiss cheese (part I): Expanding professor Reason’s model for patient safety. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, S.M.; Lanham, H.J.; Leykum, L.K.; McDaniel, R.R., Jr.; Pugh, J. Health care huddles: Managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, B.S.; Hagins, M., Jr.; Picciano, G.; King, J.A.; Marshall, D.A.; Nelson, B.; Deao, C. High reliability in healthcare: Creating the culture and mindset for patient safety. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, L.E.; Nippita, S.; Hacker, M.R.; Intondi, E.M.; Ozcelik, G.; Paul, M.E. Impact of teamwork improvement training on communication and teamwork climate in ambulatory reproductive health care. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2019, 38, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbakel, N.J.; Langelaan, M.; Verheij, T.J.; Wagner, C.; Zwart, D.L. Improving Patient Safety Culture in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. J. Patient Saf. 2016, 12, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paine, L.A.; Holzmueller, C.G.; Elliott, R.; Kasda, E.; Pronovost, P.J.; Weaver, S.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Mathews, S.C. Latent risk assessment tool for health care leaders. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2018, 38, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, C.L.; Krugman, M.; Schloffman, D.H. Leading Change to Create a Healthy and Satisfying Work Environment. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2013, 37, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, R.; Saulnier, T.; Campbell, A.; Godambe, S.A. Leveraging a Safety Event Management System to Improve Organizational Learning and Safety Culture. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.H.W.; Gang, M.; Szyld, D.; Mahoney, H. Making an “Attitude Adjustment”: Using a Simulation-Enhanced Interprofessional Education Strategy to Improve Attitudes Toward Teamwork and Communication. Simul. Healthc. 2016, 11, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frush, K.; Chamness, C.; Olson, B.; Hyde, S.; Nordlund, C.; Phillips, H.; Holman, R. National Quality Program Achieves Improvements in Safety Culture and Reduction in Preventable Harms in Community Hospitals. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2018, 44, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Spall, H.; Kassam, A.; Tollefson, T.T. Near-misses are an opportunity to improve patient safety: Adapting strategies of high reliability organizations to healthcare. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 23, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernan, A.L.; Giles, S.J.; Beks, H.; McNamara, K.; Kloot, K.; Binder, M.J.; Versace, V. Patient feedback for safety improvement in primary care: Results from a feasibility study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutlu, M.; Davis, D.; Doucet, A.; Down, A.; Schierbeck, D.; Stevens, P. Patient Safety Culture Bundle for CEOs and Senior Leaders. Healthc. Q. 2020, 22, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bishop, A.C.; Cregan, B.R. Patient safety culture: Finding meaning in patient experiences. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2015, 28, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.S.; Silveira, M.S.; Hoffmann, L.M.; Peres, M.A.; Breigeiron, M.K.; Wegner, W. Percepção da equipe multiprofissional quanto à segurança do paciente pediátrico em áreas críticas. Rev. Enferm. UFSM 2021, 1, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerven, E.; Deweer, D.; Scott, S.D.; Panella, M.; Euwema, M.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Personal, situational and organizational aspects that influence the impact of patient safety incidents: A qualitative study. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2016, 31 (Suppl. S2), 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, J.T.; Terry Fairbanks, R.J.; Gaba, D.M. Priorities Related to Improving Healthcare Safety Through Simulation. Simul. Healthc. 2018, 13 (Suppl. S1), S41–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, C. Remembering to learn: The overlooked role of remembrance in safety improvement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynor, K. Safety culture includes “good catches”. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2015, 72, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendlhofer, G.; Brunner, G.; Tax, C.; Falzberger, G.; Smolle, J.; Leitgeb, K.; Kober, B.; Kamolz, L.P. Systematic implementation of clinical risk management in a large university hospital: The impact of risk managers. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2015, 127, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, D. Targeting the Fear of Safety Reporting on a Unit Level. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2019, 49, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.; Boyd, M.; Cumin, D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad. Med. J. 2014, 90, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, F.; Schick, C.; Schwappach, D.; Kornilov, E.; Orbach-Zinger, S.; Katz, D.; Heesen, M. The Impact of a 22-Month Multistep Implementation Program on Speaking-Up Behavior in an Academic Anesthesia Department. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e1036–e1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.; Campbell, S.M. Tools for primary care patient safety: A narrative review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowsey, T.; Beaver, P.; Long, J.; Civil, I.; Garden, A.L.; Henderson, K.; Merry, A.; Skilton, C.; Torrie, J.; Weller, J. Toward a safer culture: Implementing multidisciplinary simulation-based team training in New Zealand operating theatres—A framework analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.A. Transformational leadership in nursing: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2644–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.M.; Li, J.; Oyewole-Eletu, S.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Gass, B.; Hirschman, K.B.; Mitchell, S.; Hudson, S.M.; Williams, M.V.; Project ACHIEVE Team. Understanding Facilitators and Barriers to Care Transitions: Insights from Project ACHIEVE Site Visits. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2017, 43, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.; Ozieranski, P.; Willars, J.; McKee, L.; Charles, K.; Minion, J.; Dixon-Woods, M. Walkrounds in practice: Corrupting or enhancing a quality improvement intervention? A qualitative study. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2014, 40, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echevarria, I.M.; Thoman, M. Weaving a culture of safety into the fabric of nursing. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 48, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BC Patient Safety & Quality Council (BCPSQC). Culture Change Toolbox; Health Quality BC: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017; 74p. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, N.; Edelman, S.; Sorra, J.; Gray, L. Action Planning Tool for the AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture™(SOPS®); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016; 18p.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Safer Together: A National Action Plan to Advance Patient Safety; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Boston, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission International (JCI). Sentinel Event Alert 57: The Essential Role of Leadership in Developing a Safety Culture; JCI: Oakbrook Terrace, IL, USA, 2017; Revised 2021, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, S.; Baker, K.; Butler, J. The Incident Decision Tree: Guidelines for Action Following Patient Safety Incidents. In Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation; Henriksen, K., Battles, J.B., Marks, E.S., Lewin, D.I., Orgs, Eds.; National Patient Safety Agency/Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Patients Safety Culture Surveys; AHRQ: Rockville, MD, USA, 2010.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).