Long-Term Care Insurance for Older Adults in Terms of Community Care in South Korea: Using the Framework Method

Abstract

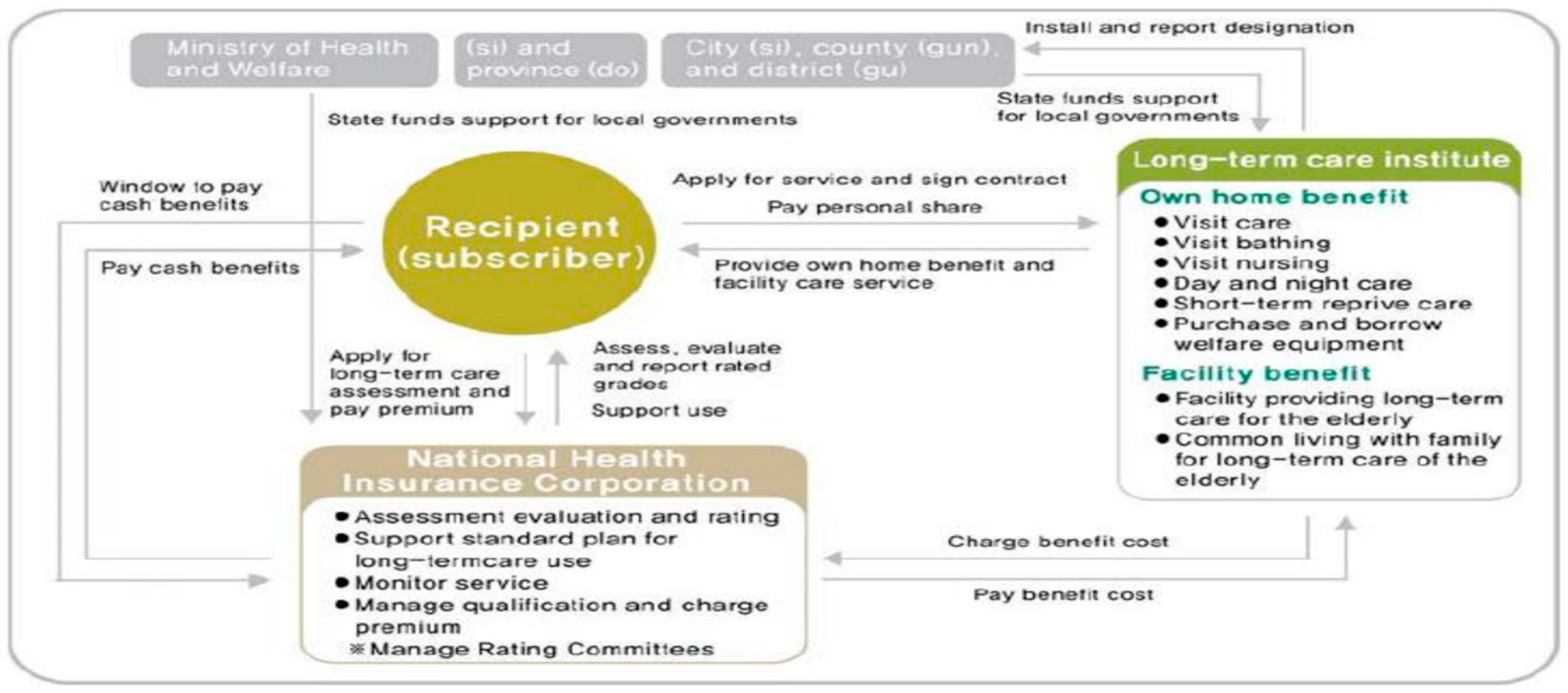

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Target of the Research

2.2. Framework Method

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Comprehensiveness Analysis

3.2. Results of the Adequacy Analysis

3.3. Results of Integration Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Implementing ‘community care’—At home community based social service provision. Press Release, 20 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Guidebook for Autonomous Implementation of Integrative Community Care; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Choi, H. The Current Status and Implications of the Elderly Long Term Care Policy in Korea. Health Welf. Policy Forum 2022, 12, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chon, Y. The meaning and challenges of the introduction of the Customized Care Services for Older Adults. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2018, 38, 10–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, M.; Chon, Y.; Lee, M.; Lee, E. Elderly Welfare Theory; Sapyoung Academy: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Insurance Service. 2021 Annual Statistics on Long-Term Care Insurance for the Elderly; National Health Insurance Service: Wonju-si, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.D. Deinstitutionalization and Building Community-Based Personal Social Services: Community Care that Connects Independence and Interdependence. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2018, 38, 492–520. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, H. Directions and Regional Zoning Strategies to Implement Community Care; Korea Social Welfare Policy Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare & Health Insurance Research Institute. Quantitative and Qualitative Surveys for Monitoring and Efficacy Analysis of Pioneering Integrative Community Care Project Monitoring and Efficacy Analysis; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare & Health Insurance Research Institute. Pioneering Integrative Community Care Project Monitoring and Efficacy Analysis (Year 3); Ministry of Health and Welfare & Health Insurance Research Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022.

- Park, D.; Cha, S. A Study on the long-term care Insurance System for the Elderly for Stable Integrated Care in the Local Community Role Recognition: Focusing on Health and Medical Welfare Workers. J. Soc. Occup. Ther. Aged Dement. 2022, 16, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Park, C. A Study on the Role of Integrated Local Community Care in the Elderly Care System in Korea in the Age of Aging. J. Community Welf. 2022, 80, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Challenges in Long-Term Care in Europe: A Study of National Policies; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, L.J. Using Framework Analysis in Applied Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; So, S. A Study on the Improvement Plan of Family Welfare Delivery System. Korean J. Local Gov. Stud. 2016, 20, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.S.; Lee, J.S. A Study on the Influential Factors of the Effectiveness of Welfare Service Delivery System for Elders. Korean Policy Sci. Rev. 2011, 15, 53–81. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Kang, E.; Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Ha, T.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Noh, S.; Lee, M.; Lim, J.; et al. A Forecast and Future Tasks for Supply Models of Care-Healthcare Joined-Up Services; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. Current Status of and Barriers to Home and Community Care in the Long-term Care System. Health Welf. Policy Forum 2018, 5, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger, T.; Puthenparambil, J.M.; Van Aerschot, L. Care poverty: Unmet care needs in a Nordic welfare state. Int. J. Care Caring 2019, 3, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Muir Health. 2022: Community Health Needs Assessment. 2022. Available online: https://www.johnmuirhealth.com/content/dam/jmh/Documents/Community/John%20Muir%20Health%20CHNA%20Report%2012.14.2022_Final.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Park, K.-S.; Lee, H.Y. Comparison of Coordinative Function between the “Hope Care Centers” in Namyangjoo Si and the “Unlimited Care Centers” in Gyeonggi Do As the Social Welfare Delivery Systems. GRI Rev. 2014, 16, 233–263. [Google Scholar]

- Leutz, W.N. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: Lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q. 1999, 77, 77–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chon, Y. The Use and Coordination of the Medical, Public Health and Social Care Services for the Elderly in Terms of Continuum of Care. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2018, 38, 10–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, B. Debate on the Topic of ‘10 Years Since Establishing a Guarantee of Long-Term Care for the Elderly and the Next 10 Years’; The Korean Academy of Long-Term Care Autumn Symposium Debate Transcript, 21 April 2017; Seoul Kim Koo Museum and Library: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Insurance Service. NHIC expands family counseling support project again in 2020. Press Release, 3 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Chon, Y.; Jo, M.; Jeon, S.; Choi, K. A Study on Measures to Re-Establish the Functions of Short-Stay Coverage; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2015.

- Ko Young-in’s Office. Dementia Family Vacation for Vacations, Less than 1% Utilization Rate. Press Releases of the State Audit, 7 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Theobald, H.; Chon, Y. Home care development in Korea and Germany: The interplay of long-term care and professionalization policies. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, 54, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Insurance Service. Regular Evaluation Results for Long-Term Care Organizations (Covered At-Home Services) in 2020; National Health Insurance Service: Wonju, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Seo, D.; Choi, T.; Kim, Y.; Kyoung, S. Development of Policy Tasks to Improve Treatment and Stabilize Supply of Caregivers; Ministry of Health and Welfare & Incheon Development Institute: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2015.

- Seo, D.M. A Study on the Stabilization of Care Workers Supply in Korea. J. Korean Long Term Care 2012, 1, 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, C.; Luppi, M. Cost-containment long-term care policies for older people across the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: A scoping review. Ageing Soc. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jeong, H.; Seok, J.; Song, H.; Seo, D.; Lee, J.; Yoo, A.; Lee, H.; Kwon, J.; Han, E.; et al. Study on the Establishment of the 2nd Basic Plan for Long-Term Care; Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2017.

| Category | Definition |

| Comprehensiveness | -Provision of ‘various types’ of home care services to meet the LTC needs of older adults. |

| Adequacy | -Provision of adequate ‘time’ and ‘quality’ of services to meet the LTC needs of older adults. |

| Integration | -‘Linkage’ of various home care services at the regional level to meet the LTC needs of older adults. |

| Category | Total | A (Excellent) | B (Good) | C (Fair) | D (Poor) | E (Fail) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Score | N | % | Score | N | % | Score | N | % | Score | N | % | Score | N | % | Score | |

| Total | 5891 | 84.6 | 2009 | 34.1 | 94.3 | 2014 | 34.2 | 85.7 | 1024 | 17.3 | 77.8 | 442 | 7.2 | 69.4 | 422 | 7.2 | 64.2 |

| Visiting care | 3540 | 85.3 | 1304 | 36.8 | 94.3 | 1214 | 34.3 | 85.7 | 594 | 16.8 | 77.7 | 253 | 7.1 | 69.2 | 175 | 4.9 | 64.4 |

| Visiting bath | 664 | 85.7 | 247 | 37.2 | 94.6 | 227 | 34.2 | 85.8 | 114 | 17.2 | 77.7 | 52 | 7.8 | 69.8 | 24 | 3.6 | 65.9 |

| Visiting nursing | 131 | 88.4 | 67 | 51.1 | 94.5 | 41 | 31.3 | 86.0 | 14 | 10.7 | 79.1 | 3 | 2.3 | 72.8 | 6 | 4.6 | 64.3 |

| Day/night care | 1053 | 84.2 | 311 | 29.5 | 94.3 | 401 | 38.1 | 85.7 | 194 | 18.4 | 77.6 | 82 | 7.8 | 68.6 | 65 | 6.2 | 65.8 |

| Short stay | 23 | 79.0 | 1 | 4.3 | 90.0 | 6 | 26.1 | 87.5 | 12 | 52.2 | 78.7 | 1 | 4.3 | 70.0 | 3 | 13.0 | 62.3 |

| Welfare devices | 480 | 77.9 | 79 | 16.5 | 94.0 | 125 | 26.0 | 86.0 | 96 | 20.0 | 78.7 | 31 | 6.5 | 72.8 | 149 | 31.0 | 63.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chon, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-Y. Long-Term Care Insurance for Older Adults in Terms of Community Care in South Korea: Using the Framework Method. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131238

Chon Y, Lee S-H, Kim Y-Y. Long-Term Care Insurance for Older Adults in Terms of Community Care in South Korea: Using the Framework Method. Healthcare. 2024; 12(13):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131238

Chicago/Turabian StyleChon, Yongho, Seok-Hwan Lee, and Yun-Young Kim. 2024. "Long-Term Care Insurance for Older Adults in Terms of Community Care in South Korea: Using the Framework Method" Healthcare 12, no. 13: 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131238

APA StyleChon, Y., Lee, S.-H., & Kim, Y.-Y. (2024). Long-Term Care Insurance for Older Adults in Terms of Community Care in South Korea: Using the Framework Method. Healthcare, 12(13), 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131238