Abstract

Cognitive restructuring (CR) aims to get people to challenge and modify their cognitive distortions, generating alternative, more adaptive thoughts. Behavioral, emotional, and physiological responses are modified by analyzing and changing dysfunctional thoughts. The person must have the cognitive capacity to participate in the analysis of their thoughts. CR for people with depression has positive effects, although there is little research on how it should be structured and applied. CR is a thought modification technique presented in the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), but is not organized in a sequential approach, and there is no procedure for applying it in practice. This scoping review aims to identify the structure, contents and assessment instruments used in CR for people with depressive symptoms and to analyze the health outcomes of applying the CR technique in this population. Out of 515 articles, seven studies were included in the review, up to 2021 and without any time limitation. The studies were not guided by a consistent and sound framework of the CR technique and each study used its own framework, although they used similar techniques. We grouped CR into six steps. No specific studies were found regarding intervention by nurses. CR is effective in reducing depressive symptoms, so it is an important therapeutic tool that should be used on people with depression. With this scoping review, mental health nurses will have a more comprehensive idea of the techniques that can be used in the application of CR to patients with depressive symptoms.

1. Introduction

Depression impacts approximately 300 to 350 million people worldwide. It is a condition that affects a person’s functioning, limiting the person’s autonomy and their role in the family and community. Since depression can appear when a person is still young, it can affect more years of their life, having a high personal and social impact [1,2].

The total number of people estimated to be living with depression increased by 18.4% between 2005 and 2015. The proportion of the global population with depression in 2015 was estimated at 4.4 percent. Depression proved to be more common among women (5.1 percent) than men (3.6 percent). This disorder is widely prevalent in the human population, impacting mood and feelings. It represents a pathological condition, and it is distinct from certain feelings such as sadness, stress, or fear that one may experience at a certain period in life [1].

In consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of depression is likely to worsen in the human population [3].

Depressive disorders are characterized by sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-esteem, changes in sleep or appetite, feelings of tiredness, and poor concentration. They include two main subcategories: major depressive disorder/depressive episode, classified as mild, moderate, or severe; and dysthymia, which presents as a persistent or chronic form of mild depression. The episodes of dysthymia are similar to a depressive episode but tend to be less intense and last longer [4].

Depression can be long-lasting or recurrent, substantially impairing a person’s ability to function at work or academically, or to cope with their day-to-day life. In its most severe presentation, depression can lead to suicide [1,4,5].

Given the data presented, it is understood that it is necessary to adopt valid strategies in reducing the incidence and impact of this disease in the population.

For mild-to-moderate depression, psychological intervention such as cognitive therapy (CT) may be recommended as a first line of treatment [6]. CT is also especially recommended, as one of the first line treatments, in the treatment of depression during pregnancy and breastfeeding by women. In this group, antidepressant medication should be avoided as much as possible [6,7,8,9]. This type of therapy can be used alone, in the treatment of mild-to-moderate depressive disorders, or combined with antidepressant medications for the treatment of major depression [8].

From this perspective of cognitivist theories, the human organism responds primarily to cognitive representations of its environment and not directly to the environment itself. These cognitive representations are related to learning processes, which are mostly cognitively mediated. Thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are observed to be causally interactive. Behaviors and emotions are related to thoughts that sustain and modulate them [8].

Cognitive therapy was developed by Aaron Beck in the 1960s, who developed a theory of depression centered on cognitive aspects, in which symptoms were related to a negative profile of thinking in three domains: self, world, and future. This theory became known as Beck’s cognitive triad. In his theory, the etiology of psychological disorders is found in the way one conceptualizes reality, with emotional disorders being the consequences of maladaptive thoughts. The author defended the existence of automatic thoughts (cognitions that arise quickly to situations that we experience and remember or project, and that are usually not subject to a more structured rational analysis) and cognitive schemas (set of ideas that reflect how the person organizes information about himself and the surrounding environment) [7,8].

Other authors also contributed to the development of cognitive therapy, such as Kelly, with the Theory of Personal Constructs (core beliefs or self-schemas), which appeared in 1955, based on the understanding of the complexity of others and oneself [7]. Similarly, Albert Ellis, with rational emotive therapy, which emerged in the 1950s, assumed that thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are always interconnected. This author argues that emotions and behaviors result, not from the events themselves, but from how people interpret them [10].

One of the cognitive intervention techniques is cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring (CR) aims to identify negative and unrealistic interpretations (cognitive distortions/dysfunctional thinking) of an event and replace them with more realistic interpretations [11]. Like most CT techniques, it assumes that perception and experience are active processes of internal and external cognitive analysis [7,8]. This intervention aims to modify the behavioral response, changing automatic thinking and consequent emotions, creating alternative behavioral responses. It aims to lead the person to question the validity of their beliefs, analyzing, and modifying them [8,12,13,14].

Throughout their personal and cognitive development, people form brain connections and core beliefs that regulate their attitude and conduct. These beliefs are behind the thoughts that arise in specific situations, such as automatic thoughts. These are interconnected with behaviour in each situation and with the emotional experience. Dysfunctional core beliefs lead to dysfunctional automatic thoughts and maladaptive behaviours, which can lead to the onset of depressive symptoms. With the help of a professional, CR aims to help people change their dysfunctional beliefs and thoughts to a more appropriate form and consequently reduce their depressive symptoms [7,12,14].

Cognitive restructuring is the most essential and theoretically the main mechanism of change [15]. CR presents itself as a useful intervention because of its practical and objective applicability, having concrete results in developing skills to cope with negative emotions and generate more adaptive responses [16,17].

The purpose of CR is based on the relief of the person’s psychological suffering by changing the way they think, as well as the way they interpret and reflect about their experiences, helping users to assess their cognitions not as indisputable facts, but as hypotheses to be tested against logical evidence [7,8,18]. CR is defined in the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), with code 4700, meaning a “challenge to the patient to alter distorted patterns of thinking and perceive themselves and the world more realistically”. Although a set of nursing activities corresponding to CR are defined in the NIC, they are not organized in a sequential approach, and there is no procedure for applying CR in practice [19].

Taking into account the above, the need arose to conduct detailed research on the application of CR to people with depressive symptoms to analyze the contents and the procedures used in the application of this therapy, and for the interest and usefulness it has in practice as a specialized intervention in mental health nursing. For this purpose, a scoping review (ScR) on the CR applied to people with depressive symptoms was conducted.

The main aims of this review were to identify the structure, contents, and assessment instruments used in cognitive restructuring for people with depressive symptoms and to analyze the health outcomes of applying the cognitive restructuring technique to people with depressive symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the updated scoping review guidance of Pollock et al. [20], this scoping review followed the JBI ScR framework and the PRISMA-ScR extension. The following steps were followed: (1) identify the research questions, (2) identify pertinent studies, (3) select the studies, (4) map the data obtained, (5) gather, summarize, and report the data [21,22].

The scoping review protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/jyqsv (accessed on 13 December 2020).

As recommended in the guidelines for scoping reviews, we formulated the research questions based on the ‘PCC’ format: Population, Concept, and Context [23].

Question 1: What are the characteristics (structure, contents, and assessment instruments) of cognitive restructuring used in people with depressive symptoms?

- -

- Population: people with depressive symptoms,

- -

- Concept: the structure, contents and assessment instruments of cognitive restructuring,

- -

- Context: all clinical settings where the target population undergoes cognitive restructuring.

Question 2: What are the health outcomes of applying the cognitive restructuring technique to people with depressive symptoms?

- -

- Population: people with depressive symptoms,

- -

- Concept: the health outcomes of applying the cognitive restructuring technique,

- -

- Context: all clinical settings where the target population undergoes cognitive restructuring.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criterion for inclusion were studies on cognitive restructuring (CR) applied to people with depressive symptoms, which included the structure and content of the intervention. Initially, we searched for primary and secondary studies on the subject in a 10-year timeframe. Due to the small amount of specific information available on the subject under study, we changed the search to an open-ended one to map the largest amount of information.

The languages defined as criteria were English, Portuguese, and Spanish, due to the vast amount of information they allow us to map. These languages are the ones most fluently mastered by the reviewers in the study. This ensured that the selection and analysis of the ScR process had the utmost rigor.

Studies involving children were excluded, due to the specificity of the interventions in this age group. Psychotherapeutic interventions with children differ in structure and content, because children are at a very different stage of cognitive development from the adult population. It was decided not to exclude the adolescent age group, due to the similarity of some interventions, in original or adapted form, used in both adults and adolescents. Adolescents have a more developed understanding of cognitive processes than children.

By adolescent we mean a person between the ages of 13 and 18, and by adult we mean a person over the age of 18 [24].

2.2. Search Strategy

To minimize bias in the ScR results, the screening and data extraction process was performed by two independent reviewers and a third reviewer to analyze discrepancies.

The databases included MEDLINE with full text (via EBSCOhost); CINAHL plus with full text (via EBSCOhost); Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection (via EBSCOhost); Academic Search Complete (via EBSCOhost); SPORTDiscus with full text (via EBSCOhost); RCAAP; ARROW; Australian National University-open research; and OpenGrey.

The methodological strategy of the search, to include information from the grey literature, was due to the existence of various types of documents of practical and scientific interest (at the private or organizational level), increasing the relevant information to map [21].

The database search was performed in April 2021.

With support from the selected databases, the keywords were determined based on vocabulary terms from the medical subject heading (MeSH), which best translated the focus of the search to allow a consistent means of searching for the information [24]. The following terms were identified: “cognitive restructuring”, “depression”, and “depressive symptoms”.

The term cognitive restructuring does not appear as an exact term in the descriptors in DeSC or MeSH, being, however, a relevant term for our search. It was thus considered relevant by the researchers to include this term, allowing for more precise information to be sought. We also agree that the inclusion of this term in the Boolean phrase would not limit the search in scientific databases, due to the way it is constructed.

The search was performed with the following Boolean phrase: (“cognitive restructuring” OR “cognitive therapy”) AND (“depression” OR “depressive symptoms”) NOT “child”.

All types of studies found were included, with the rationale that the ScR should be based on data from any type of evidence and research methodology and is not restricted to only quantitative studies (or any other study design) [25].

2.3. Study Selection and Extraction

Data selection and extraction was done based on the template instrument presented by JBI for extracting details, characteristics, and outcomes [25]. These instruments were adapted based also on the objectives of the review. The title and abstract were read, according to the previously established search and inclusion criteria. A full text analysis of the articles was performed on those that met the selected criteria as described in the study protocol.

Articles in which both reviewers agreed on their interest for the research were included. Whenever there was no agreement between the reviewers, a discussion with a third reviewer was used. From the selected articles, an analysis of the reference lists was performed, first by the title, followed by an analysis of the abstracts considered relevant, and then by an analysis of the full text. Additional relevant articles that were not duplicated were included in the ScR.

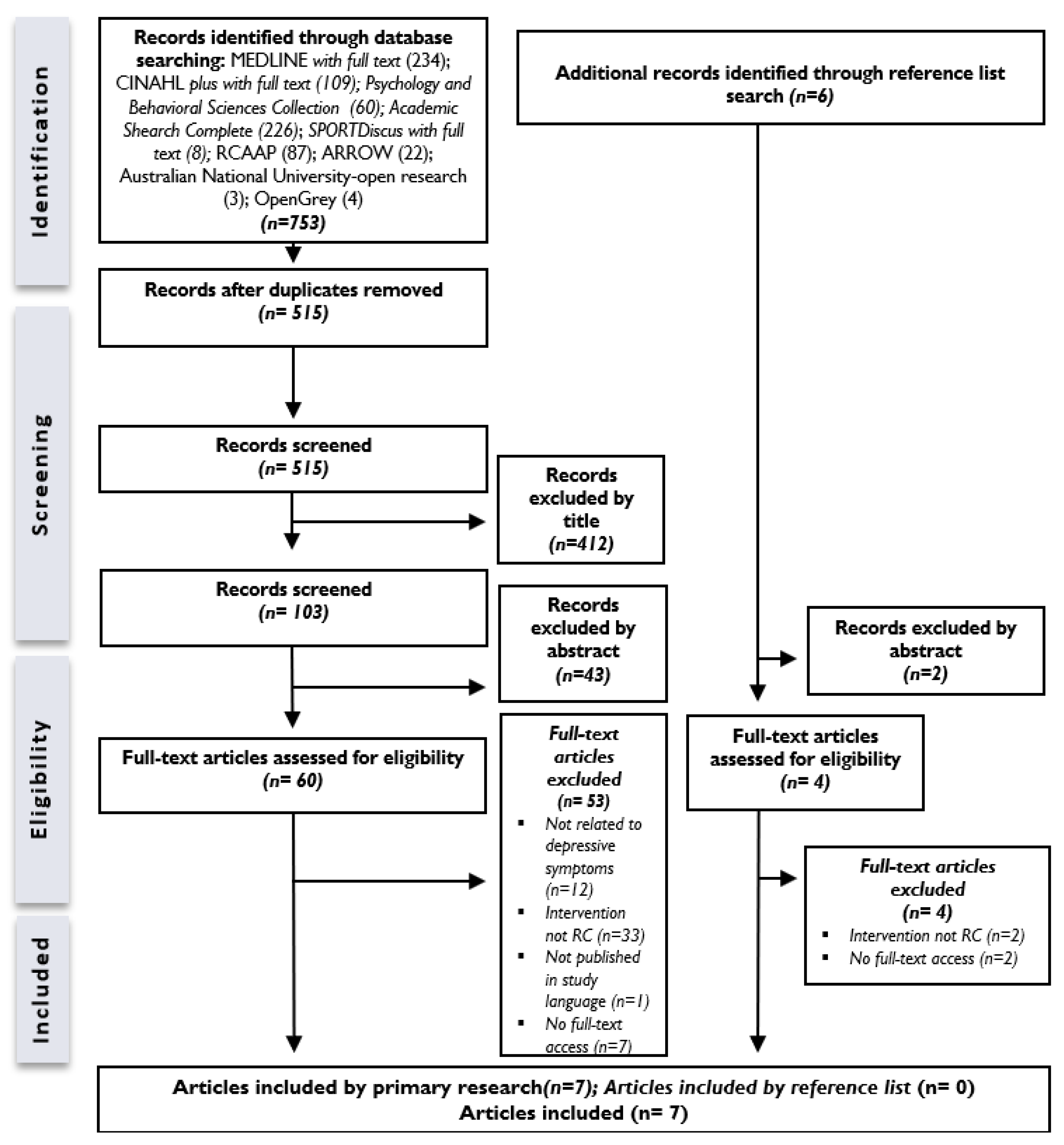

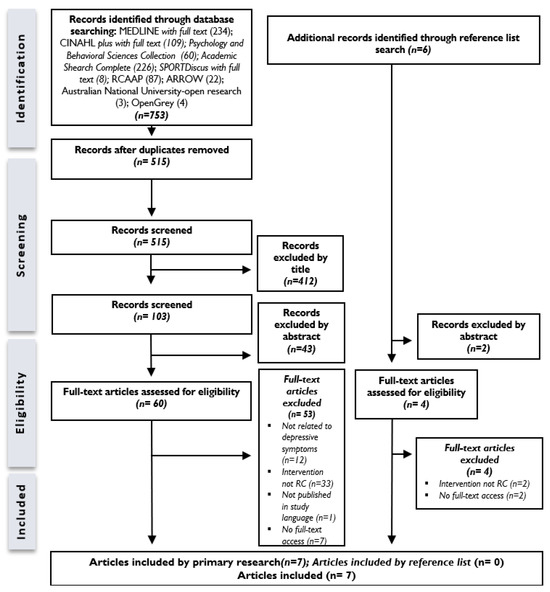

In the search, after removing duplicate records, 515 records were found. After the screening process, 60 articles were selected for full-text analysis. By the eligibility criteria, 7 articles were selected for inclusion in the ScR.

The information search and selection process are summarized in Figure 1—PRISMA, a flow chart demonstrating search the strategy.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart demonstrating search strategy.

3. Results

According to the mapped studies, CR sessions range from micro-interventions of one session [26,27] to three sessions [28], longer interventions of eight sessions [29], and nine to twelve sessions [30] or sixteen sessions [31]. Shorter interventions were conducted on consecutive days [28] and longer interventions were conducted on a weekly [31] or bi-weekly basis [29]. The duration of each session ranged from 60 min [29] to 90 min [12] or 120 min [30]. Only one of the studies performed a follow up, which took place after 6 months [32]. In all studies, the reference technician was the psychologist.

One exploratory study aimed to identify the evolution of cognitive restructuring techniques, with results indicating that in the most successful cases of CR, a greater number and frequency of techniques are used [31].

Three articles are experimental studies, with two of these studies demonstrating the usefulness of CR in reducing depressive symptoms [29,32], and one finding that a combination of emotional processing (EP) and CR was the most effective intervention, compared with the single use of each of these two interventions [28].

One study is a pilot study with a sample of female cancer patients and proved the effectiveness of CR in reducing depressive symptoms [27].

Another two articles are randomized controlled trials (RCT), which also obtained therapeutic improvements with CR in people with depressive symptoms [26,30]. Table 1 describes a summary of the included articles.

Table 1.

Studies, aims and main results.

The assessment instruments used in the studies are shown in Table 2. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) was the most used instrument to assess depressive symptoms [26,27,28,30,31], with the remaining instruments not repeated in any of the other studies.

Table 2.

Assessment Instrument.

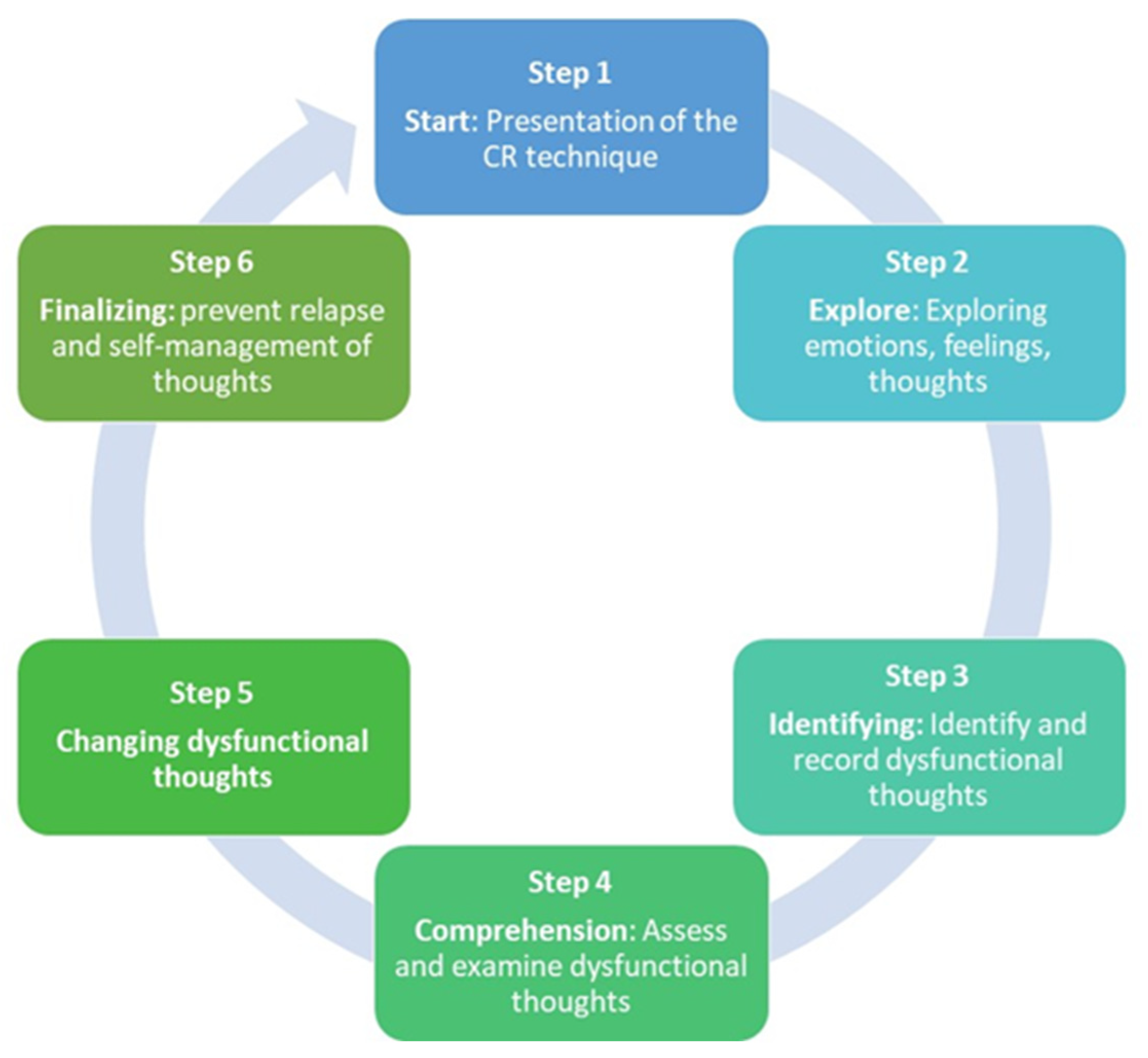

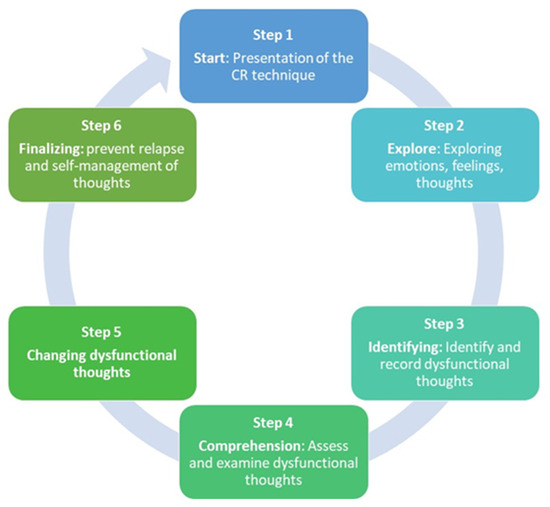

Table 3 shows the structure and techniques used in the studies when using CR. For better structuring and organization of the sessions we grouped the techniques into the following steps: Start; Explore; Identifying; Comprehension; Changing Beliefs; and Finalizing. We also present conducts that should be present in all sessions.

Table 3.

CR Structure and Techniques.

The steps shown in Table 3 are summarized in Figure 2. This figure shows the structure that emerges from the results analyzed in the studies included in the ScR.

Figure 2.

Cognitive Restructuring Structure.

4. Discussion

The results of applying CR demonstrate a reduction in depressive symptoms [26,27,28,29,31,33]. In addition to reducing depressive symptoms, CR has also been shown to be effective in improving self-esteem and reducing stress levels [29]. One study indicates that clinical improvement usually comes after the 6th–8th session [34]. However, one study indicates that even with a single session, positive effects can already be detected [32]. CR is an important non-pharmacological intervention for people with depression.

The application of CR requires a complete mastery of the focus of intervention, as well as dynamic skills and therapeutic creativity, in order to maintain the fluidity of the sessions and a relationship of trust with the person assisted. Given the diversity of techniques applied in CR, the therapist must have a high level of mastery of them. Results indicate that in the most successful cases of CR, a greater number and frequency of techniques are used [31]. The number of strategies increases in frequency between the 1st and 8th sessions and, consequently, in the last sessions (12th and 16th). In these sessions, the number of strategies is no longer so evident, since the process is being completed and the therapist no longer needs to frequently use the different strategies [31].

The diversity and flexibility in the application of CR is related to the need to adapt the techniques to each person [13], although the results of this scoping review also point to a standard structure and goals defined in the sequence of sessions. The sessions are linked by a logical sequence, which allows cognitive and behavioral modifications to be integrated. CR also appears to have a greater number of conventional presentations [35]. More structured and objective psychotherapeutic interventions bring very satisfactory and shorter-term results than longer and subjective interventions [36]. However, in some situations, the CR intervention may require a larger number of sessions than usual [37]. The number and duration of the CR sessions was variable, which shows flexibility in its applicability, with CR seeming to move away from more rigid and lengthy models. Decreased cognitive flexibility and executive ability can lead to difficulty integrating CR and achieving positive results [38]. Thus, in addition to the importance of structuring the CR technique, it is also important to carry out an individual cognitive conceptualization treatment plan [7]. A recent integrative literature review concluded that care plans for people with depression should be individualized, dynamic, flexible, and participatory [39], which is in line with this perspective.

Psychotherapeutic intervention, including CR, should focus on adapting the techniques to each person, their internal processes, and personal experiences. The need to establish an empathic and trusting relationship is emphasized to achieve success in CR [40].

Through analysis of the various articles in this scoping review, we were able to group CR by steps, the first step being the presentation of the therapist and participant and an explanation of the intervention, as well as its goals. This first step is fundamental for the beginning of the relationship and the success of the intervention and will support step 2, which is the exploration phase where the problem is explored, being crucial for the catharsis and the identification of emotions, feelings, and thoughts. If we think of Peplau’s theory [41], we can make a link and say that these first two steps correspond to the orientation phase. Step 3 is the identification and recording of dysfunctional thoughts (automatic thoughts, rumination, negative thoughts, irrational beliefs, etc.). We can say that it would correspond to the identification phase of Peplau’s theory. In step 4, it is intended that there is an understanding of dysfunctional thoughts through their evaluation and analysis, making the person aware of cognitive errors. This step could correspond to the exploration phase of Peplau’s theory. In step 5, the goal is to change the beliefs and cognitive errors, that is, through the analysis performed in step 4, it is intended that the person becomes aware of their thoughts and dysfunctional beliefs and changes attitudes and behaviors. The completion phase is intended to prepare the person to prevent relapse and to self-manage their dysfunctional thoughts in their daily life. Steps 5 and 6 would correspond to the resolution phase of Peplau’s theory.

The need to establish a structure for psychotherapeutic interventions, such as CR, is highlighted by some authors [42,43].

For the assessment of CR outcomes in relation to depressive symptoms, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) was the most commonly used instrument [26,27,28,30,31]. However, other authors have used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [32], the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) and the Geriatric Depression Scale of Yesavage (GDS) [29]. Instruments were also used to assess Self-Esteem [29], Resilient level [29], Subjective discomfort; Interpersonal relationships; Social role performance [31], Social support, Cognitive Symptoms, Basic activities of daily life [29], Satisfaction with Life [28,29] and Pet-Related Distress [28].

In the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) manual, cognitive restructuring emerges as a relevant technique in nursing care that supports psychosocial functioning and facilitates life changes [19]. However, no studies emerged in our research in which the therapist was a nurse. These results indicate the need for a greater focus on evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions by specialist nurses in mental health and psychiatry, as well as the dissemination of research studies. This scoping review aims to be a first step towards the increased use of this type of interventions by specialist nurses, as a basis for the application of CR to people with depression.

According to the Psychotherapeutic Intervention Model in Nursing, cognitive restructuring can be used as a psychotherapeutic intervention by the nurse specialist in mental health and psychiatric nursing, always based on a nursing diagnosis [42,43]. There are several nursing diagnoses in which the psychotherapeutic intervention of cognitive restructuring can be used, but its use requires specialized knowledge in this diagnostic assessment.

There are very few research studies that have used the cognitive restructuring technique with people with depression and we have only found two RCTs. We did not find any studies where the therapist was a mental health nurse specialist. This ScR reflects the need for primary research into CR carried out by mental health nurses on people with depressive symptoms.

5. Conclusions

CR is effective in reducing depressive symptoms, improving self-esteem, and reducing stress levels, so it is an important therapeutic tool that should be used on people with depression. The few research studies that have applied CR suggest that there is a need for greater investment in this type of non-pharmacological intervention to help people manage their dysfunctional thoughts and thereby reduce depressive symptoms and disability.

Although the information on CR was scattered and not standardized, it was possible to map and characterize the intervention. The studies were not guided by a consistent and sound framework of the CR technique and each study used its own framework, although they used similar techniques. This suggests the need for a structured manual to support the interventions to make their application more rigorous and less subjective. It is our intention to continue researching this subject in order to draw up a support manual with different steps and strategies to help implement CR. In practice, a manual will help provide specific training on the CR technique. The different stages, structure, and content of CR resulting from this research could contribute to define further steps of more advanced research. We emphasize, however, the importance of adapting the techniques to each person’s individuality and needs. The existence of a manual of RC, does not eliminate the need for personalized adjustments to meet people’s specific needs, ensuring a more effective and person-centered approach. Although CR is documented in the NIC, there is no structured CR intervention for nursing intervention based on focus nursing. Besides that, no specific studies were found referring to the intervention of nurses. This suggests the need to group and structure the data obtained for the construction of a psychotherapeutic intervention in CR nursing through consultation with mental health nursing experts so that nurses can then use evidence-based CR. This ScR was the first step in a broader investigation that we intend to carry out, namely the conduct of a focus group, a pilot study, and a randomized controlled trial, to obtain a scientifically validated and structured CR intervention aimed at differentiated intervention for mental health nurses. The identification of seven records for analysis in the ScR also suggests the need for primary research into CR in people with depressive symptoms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S., C.S. and P.M.-C.; formal analysis, B.S., L.P. and P.M.-C.; investigation, B.S., L.P., R.P. and P.M.-C.; methodology, B.S., L.P., R.P., C.S. and P.M.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S., R.P., M.J.N. and L.P.; writing—review and editing, B.S., L.P., M.J.N., C.S. and P.M.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; No. WHO/MSD/MER/2017.2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and Columbia University. Group Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) for Depression, version 1.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; No. WHO/MSD/MER/16.4. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, L.G.; Correia, T.; Lopes, M.; Fonseca, C.; Marques, M.C.; Sampaio, F.; Reis, A. Patient-Centered Care for People with Depression and Anxiety: An Integrative Review Protocol. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Manual de Diagnóstico e Estatística das Perturbações Mentais, 5th ed.; Climepsi Editores: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, B.; Lutz, W. The state of nursing science—Cultural and lifespan issues in depression: Part I: Focus on adults. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 28, 707–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Humanitarian Intervention Guide (mhGAP-HIG): Clinical Management of Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Conditions in Humanitarian Emergencies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548922 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Beck, J. Terapia Cognitiva: Teoria e Prática; Artes Médicas: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sadock, B.J.; Sadock, V.A.; Ruiz, P. Compêndio de Psiquiatria: Ciência do Comportamento e Psiquiatria Clínica, 11th ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Uguz, F.; Ak, M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in pregnant women with generalized anxiety disorder: A retrospective cohort study on therapeutic efficacy, gestational age and birth weight. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 43, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.J. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy and Individual Psychology. J. Individ. Psychol. 2017, 73, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowlan, J.; Wuthrich, V.; Rapee, R.; Kinsella, J.; Barker, G. A Comparison of Single-Session Positive Reappraisal, Cognitive Restructuring and Supportive Counselling for Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2016, 40, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Rush, A.J.; Shaw, B.F.; Emery, G. Terapia Cognitiva da Depressão; Artes Médicas: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnco, C.; Wuthrich, V.M.; Rapee, R.M. The Impact of Late-Life Anxiety and Depression on Cognitive Flexibility and Cognitive Restructuring Skill Acquisition. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, O. Terapias Cognitivas: Teoria e Prática; Edições Afrontamento: Porto, Portugal, 1993; ISBN 9789723602852. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, J.D. The building blocks of treatment in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Israel J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2009, 46, 245–250. Available online: https://cdn.doctorsonly.co.il/2011/12/2009_4_2.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Marquart, A.L.; Overholser, J.C.; Peak, N.J. Mood regulation beliefs in depressed psychiatric inpatients: Examining affect, behavior, cognitive, and social strategies. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2009, 13, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddimath, B. Effectiveness of rational emotive behavior therapy on depression and general health among literate unemployed. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2014, 5, 698–701. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=a9h&AN=97600647&site=ehost-live&scope=site (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Clark, D.M. Anxiety disorders: Why they persist and how to treat them. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 37, S5–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulechek, G.M.; Butcher, H.K.; Dochterman, J.M.; Wagner, C. Classification of Nursing Interventions, 6th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, D.; Davies, E.; Peters, M.; Tricco, A.C.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; Zachary, M. Undertaking a scoping review: A practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Science Descriptors. Available online: http://decs.bvsalud.org (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Baldini Soares, C.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. Scoping Reviews. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deldin, P.J.; Chiu, P. Cognitive restructuring and EEG in major depression. Biol. Psychol. 2005, 70, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asuzu, C.C.; Akin, O.E.O.; Philip, E.J. The effect of pilot cognitive restructuring therapy intervention on depression in female cancer patients. Psycgo-Oncology 2015, 25, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.; Schloss, H.; Moonat, S.; Poulos, S.; Wieland, J. Emotional processing versus cognitive restructuring in response to a depressing life event. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2007, 31, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.; Atiénzar, A.P.A.; Mayordomo, T.; Satorres-Pons, E.; Meléndez, J.C. Efectos de la terapia cognitivo-conductual sobre la depresión en personas mayores institucionalizadas. Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clín. 2015, 20, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderka, I.M.; Gillihan, S.J.; McLean, C.P.; Foa, E.B. The Relationship Between Posttraumatic and Depressive Symptoms During Prolonged Exposure With and Without Cognitive Restructuring for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T. Therapist Interventions in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Exploratory Study on the Use of Cognitive Restructuring. Master’s Thesis, Maia University Institute, Maia, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zaunmüller, L.; Lutz, W.; Strauman, T.J. Affective impact and electrocortical correlates of a psychotherapeutic microintervention: An ERP study of cognitive restructuring. Psychother. Res. 2014, 24, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, C.; Rogers, J.; Wood, A. Depression: Cognitive Behaviour Therapy with Children and Young People, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Filimon, L. Cognitive restructuring and improvement of symptoms with cognitive-behavioural therapy and pharmacotherapy in patients with depression. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréchette-Simard, C.; Plante, I.; Bluteau, J. Strategies included in cognitive behavioral therapy programs to treat internalized disorders: A systematic review. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018, 47, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, L.L.; Padesky, C.A.; Hollon, S.D.; Mancuso, E.; Laposa, J.M.; Brozina, K.; Segal, Z.V. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression using mind over mood: CBT skill use and differential symptom alleviation. Behavior Ther. 2017, 48, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, V.B.; Abreu, N.; Oliveira, I.R.D.; Sudak, D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2008, 30, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnco, C.; Wuthrich, V.M.; Rapee, R.M. The role of cognitive flexibility in cognitive restructuring skill acquisition among older adults. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, L.G.; Lopes, M.; Correia, T.; Sampaio, F.; Arco, H.R.d.; Mendes, A.; Marques, M.d.C.; Fonseca, C. Patient-Centered Care for Patients with Depression or Anxiety Disorder: An Integrative Review. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; Artmed: São Paulo, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau, H. Relaciones Interpersonales en Enfermeira; Salvat Editores: Barcelona, Spain, 1990; pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, F.M.C.; Sequeira, C.; Lluch Canut, T. Content Validity of a Psychotherapeutic Intervention Model in Nursing: A Modified e-Delphi Study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C.; Sampaio, F. Mental Health Nursing: Diagnoses and Interventions; LIDEL: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).