The Connection between Sleep Patterns and Mental Health: Insights from Rural Chinese Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measurement of Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

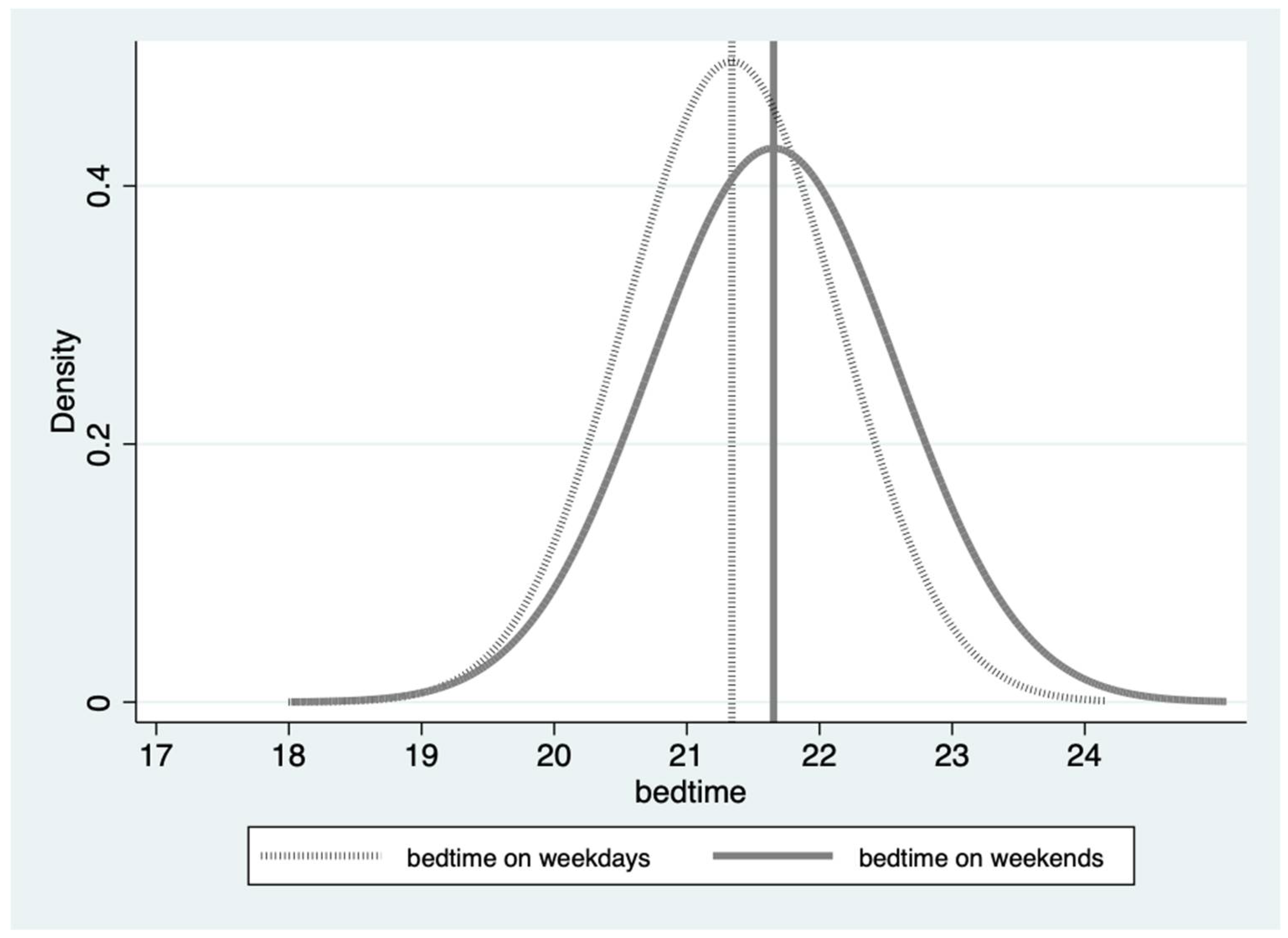

3.2. Students’ Mental Health Status and Sleep Patterns

- The average bedtimes provided for weekdays and weekends (“Bedtime on weekdays, o’clock” and “Bedtime on weekends, o’clock”) are calculated by averaging the precise minute each respondent reported going to bed. This method ensures that the calculated bedtimes accurately represent the typical sleep patterns of the study population by summarizing individual responses.

- This category includes any students who reported symptoms of depression. The mean value of 0.327 indicates that 32.7% of students reported varying levels of depression symptoms. These symptoms are further classified into mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe categories, based on their severity levels. Percentages for mild (9.7%), moderate (14.3%), severe (5.1%), and extremely severe (3.6%) categories are calculated from the subset of students who reported experiencing depression symptoms, constituting 32.7% of the total sample. This breakdown helps to understand the distribution of symptom severity among students reporting depression. Similarly, this interpretation applies to the anxiety and stress scales of the DASS.

3.3. Correlating Factors of Sleep Patterns for Rural Students: Weekdays vs. Weekends

3.4. Correlation between Students’ Sleep Patterns and Mental Health

3.4.1. OLS Regression of Student Sleep Patterns and Mental Health

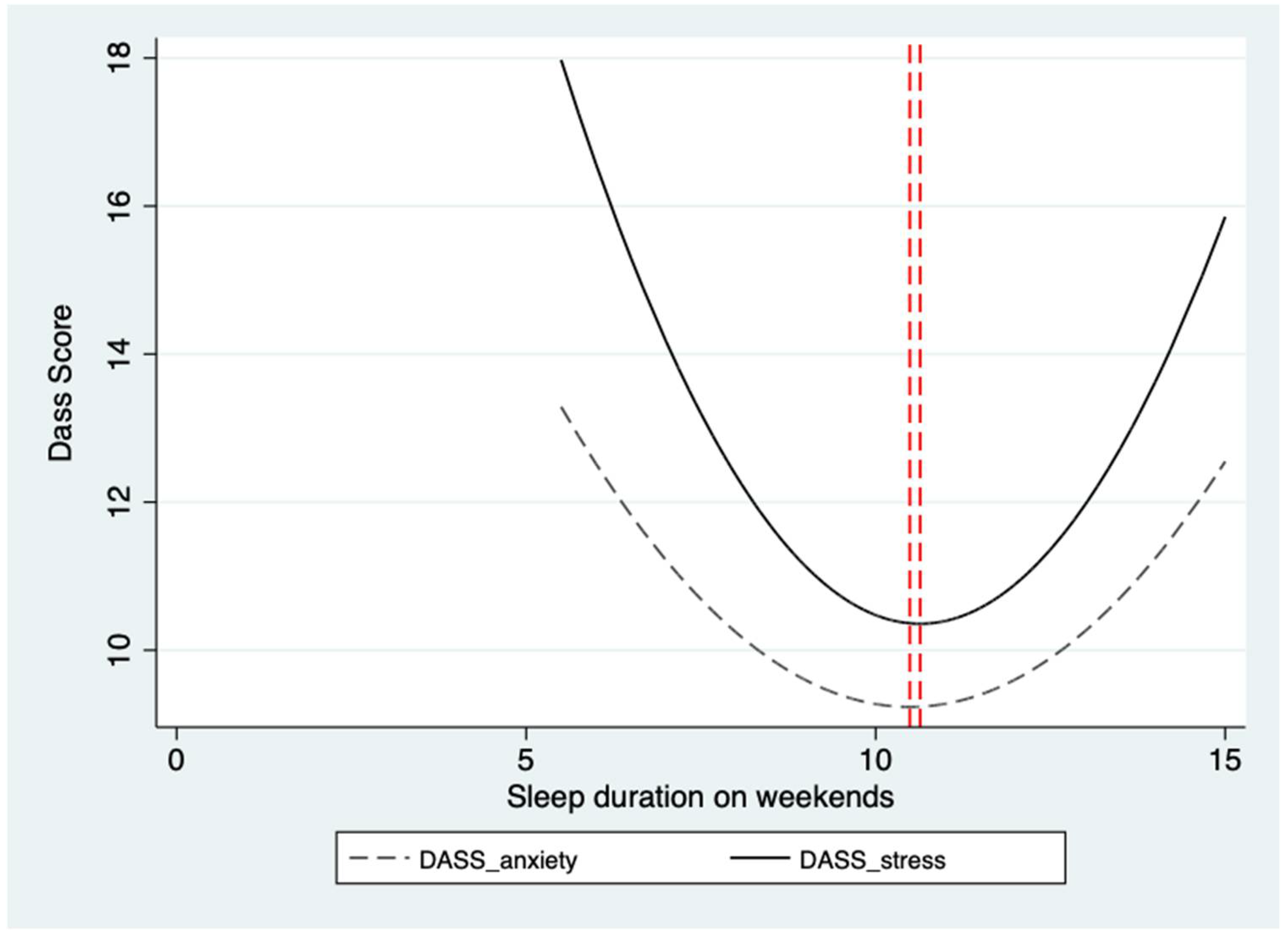

3.4.2. The “U-Shaped” Relationship between Student Sleep Patterns and Mental Health

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Sleep Patterns and Mental Health in Young Students

4.2. The “U-Shaped” Relationship on Weekends

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kopasz, M.; Loessl, B.; Hornyak, M.; Riemann, D.; Nissen, C.; Piosczyk, H.; Voderholzer, U. Sleep and memory in healthy children and adolescents—A critical review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, B.; Taveras, E.; Allender, S.; Strugnell, C. Sleep and obesity among children: A systematic review of multiple sleep dimensions. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potkin, K.T.; Bunney, W.E. Sleep improves memory: The effect of sleep on long term memory in early adolescence. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosi, A.; Calestani, M.V.; Parrino, L.; Milioli, G.; Palla, L.; Volta, E.; Brighenti, F.; Scazzina, F. Weight status is related with gender and sleep duration but not with dietary habits and physical activity in primary school Italian children. Nutrients 2017, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.C.; Meldrum, R.C. The Impact of Sleep Duration on Adolescent Development: A Genetically Informed Analysis of Identical Twin Pairs. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzierzewski, J.M.; Ravyts, S.G.; Dautovich, N.D.; Perez, E.; Schreiber, D.; Rybarczyk, B.D. Mental health and sleep disparities in an urban college sample: A longitudinal examination of White and Black students. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1972–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghrouz, A.K.; Noohu, M.M.; Dilshad Manzar, M.; Warren Spence, D.; BaHammam, A.S.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Physical activity and sleep quality in relation to mental health among college students. Sleep Breath. 2019, 23, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, M.A.; Gradisar, M.; Lack, L.C.; Wright, H.R. The impact of sleep on adolescent depressed mood, alertness and academic performance. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agathaõ, B.T.; Lopes, C.S.; Cunha, D.B.; Sichieri, R. Gender differences in the impact of sleep duration on common mental disorders in school students. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneita, Y.; Yokoyama, E.; Harano, S.; Tamaki, T.; Suzuki, H.; Munezawa, T.; Nakajima, H.; Asai, T.; Ohida, T. Associations between sleep disturbance and mental health status: A longitudinal study of Japanese junior high school students. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, L.; Olds, T.; Petkov, J. In search of lost sleep: Secular trends in the sleep time of school-aged children and adolescents. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Chen, S.; Quan, S.F.; Silva, G.E.; Ackerman, C.; Powers, L.S.; Roveda, J.M.; Perfect, M.M. Sleep patterns and sleep deprivation recorded by actigraphy in 4th-grade and 5th-grade students. Sleep Med. 2020, 67, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, O.; Malorgio, E.; Doria, M.; Finotti, E.; Spruyt, K.; Melegari, M.G.; Villa, M.P.; Ferri, R. Changes in sleep patterns and disturbances in children and adolescents in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Sleep Med. 2022, 91, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, J.; Axelsson, J.; Gerhardsson, A.; Tamm, S.; Fischer, H.; Kecklund, G.; Åkerstedt, T. Mood impairment is stronger in young than in older adults after sleep deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loessl, B.; Valerius, G.; Kopasz, M.; Hornyak, M.; Riemann, D.; Voderholzer, U. Are adolescents chronically sleep-deprived? An investigation of sleep habits of adolescents in the Southwest of Germany. Child Care Health Dev. 2008, 34, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Hay, E.L. Risk and Resilience Factors in Coping with Daily Stress in Adulthood: The Role of Age, Self-Concept Incoherence, and Personal Control. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1132–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.; McKelvie, S. Self-esteem and body satisfaction in male and female elementary school, high school, and university students. Sex Roles 2004, 51, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, S.; Musich, S.; Hawkins, K.; Alsgaard, K.; Wicker, E.R. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2016, 37, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Stewart, D. Age and Gender Effects on Resilience in Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2007, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.; Dong, Q.; Xia, Y. Age and gender differences in the self-esteem of Chinese children. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 137, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.Y.; Mo, H.Y.; Potenza, M.N.; Chan, M.N.M.; Lau, W.M.; Chui, T.K.; Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.Y. Relationships between severity of internet gaming disorder, severity of problematic social media use, sleep quality and psychological distress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Xia, N.; Zou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Y. Smartphone addiction may be associated with adolescent hypertension: A cross-sectional study among junior school students in China. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Peng, S.; Barnett, R.; Wu, D.; Feng, X.; Oliffe, J.L. Association between bedtime and self-reported illness among college students: A representative nationwide study of China. Public Health 2018, 159, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, K.; Gao, X.; Wang, G. The role of sleep quality in the psychological well-being of final year undergraduatestudents in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Dimitriou, D.; Halstead, E.J. Sleep, Anxiety, and Academic Performance: A Study of Adolescents from Public High Schools in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 678839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.J.; Baek, S.H.; Chu, M.K.; Yang, K.I.; Kim, W.J.; Park, S.H.; Thomas, R.J.; Yun, C.H. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and lower body mass: Population-based study. Sleep 2017, 40, zsx089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemieux, T.; Milligan, K.; Schirle, T.; Skuterud, M. Initial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Canadian labour market. Can. Public Policy 2020, 46, S55–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ling, J.; Zhu, X.; Lee, T.M.C.; Li, S.X. Associations of weekday-to-weekend sleep differences with academic performance and health-related outcomes in school-age children and youths. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 46, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armand, M.A.; Biassoni, F.; Corrias, A. Sleep, Well-Being and Academic Performance: A Study in a Singapore Residential College. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 672238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Deng, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, G.; Gao, X.; Li, P.; Wu, H.; Pan, S.; Zhang, W.H.; et al. Association between sleep duration, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempts among Chinese adolescents: The moderating role of depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Mao, Z.; Wang, F.; Huo, W.; Liu, R.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Z.; Liu, X.T.; Zhang, X.; et al. Abnormal night sleep duration and poor sleep quality are independently and combinedly associated with elevated depressive symptoms in Chinese rural adults: Henan Rural Cohort. Sleep Med. 2020, 70, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.P.; Wang, X.T.; Liu, Z.Z.; Wang, Z.Y.; An, D.; Wei, Y.X.; Jia, C.X.; Liu, X. Depressive symptoms are associated with short and long sleep duration: A longitudinal study of Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 263, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemola, S.; Perkinson-Gloor, N.; Brand, S.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.F.; Grob, A. Adolescents’ Electronic Media Use at Night, Sleep Disturbance, and Depressive Symptoms in the Smartphone Age. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovato, N.; Gradisar, M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: Recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med. Rev. 2014, 18, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, F.; Gregory, A.M.; Gradisar, M.; Reynolds, S. Self-reported sleep patterns and quality amongst adolescents: Cross-sectional and prospective associations with anxiety and depression. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2020, 61, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Duong, H.T. Depression and insomnia among adolescents: A prospective perspective. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 148, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China). The 2015 1% National Population Sample Survey of the People’s Republic of China; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China). China Statistical Yearbook 2018; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Golley, J.; Kong, S.T. Inequality in Intergenerational Mobility of Education in China. China World Econ. 2013, 21, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ye, J.; Li, Z.; Xue, S. How and why do Chinese urban students outperform their rural counterparts? China Econ. Rev. 2017, 45, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Education Development in China: Education Return, Quality, and Equity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shao, S.; Li, L. Agricultural inputs, urbanization, and urban-rural income disparity: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 55, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Wang, H.; Huan, J.; Du, K.; Zhao, J.; Boswell, M.; Shi, Y.; Iyer, M.; Rozelle, S. Health seeking behavior among rural left-behind children: Evidence from Shaanxi and Gansu provinces in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y. The effect of boarding on the mental health of primary school students in western rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Review of China’s agricultural and rural development: Policy changes and current issues. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2009, 1, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.H.; Woronov, T.E. Demanding and resisting vocational education: A comparative study of schools in rural and urban. China Comp. Educ. 2013, 49, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, A.; Tang, B.; Shi, Y.; Tang, J.; Shang, G.; Medina, A.; Rozelle, S. Rural education across China’s 40 years of reform: Past successes and future challenges. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Employment, emerging labor markets, and the role of education in rural China. Rev. Econ. Dev. 2002, 16, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Thompson, R.G.; Seiter, N.S.; Miller, R.L.; Crain, T.L. Does dispositional mindfulness buffer the links of stressful life experiences with adolescent adjustment and sleep? Stress Health 2021, 37, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Xie, X.; Xu, R.; Yuejia, L. Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 18, 443–446. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.N.; Lau, J.T.; Mak, W.W.; Zhang, J.; Lui, W.W. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale among Chinese adolescents. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.; Adolescent Sleep Working Group; Committee on Adolescence; Au, R.; Carskadon, M.; Millman, R.; Wolfson, A.; Braverman, P.K.; Adelman, W.P.; Breuner, C.C.; et al. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: An update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e921–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, A.G.; Jones, S.E.; Cooper, A.C.; Croft, J.B. Short Sleep Duration Among Middle School and High School Students—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwisch, J.E.; Babiss, L.A.; Malaspina, D.; Turner, J.B.; Zammit, G.K.; Posner, K. Earlier parental set bedtimes as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation. Sleep 2010, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, B.; Harvey, A.G.; Lundervold, A.J.; Hysing, M. Sleep problems and depression in adolescence: Results from a large population-based study of Norwegian adolescents aged 16-18 years. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Paksarian, D.; Lamers, F.; Hickie, I.B.; He, J.; Merikangas, K.R. Sleep Patterns and Mental Health Correlates in US Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2017, 182, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claussen, A.H.; Dimitrov, L.V.; Bhupalam, S.; Wheaton, A.G.; Danielson, M.L. Short Sleep Duration: Children’s Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders and Demographic, Neighborhood, and Family Context in a Nationally Representative Sample, 2016–2019. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, 220408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Morales-Muñoz, I. Associations between sleep and mental health in adolescents: Results from the UK millennium cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Gao, T.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ren, H.; Liang, L.; Li, C.; Mei, S. Clustering of lifestyle factors and the relationship with depressive symptoms among adolescents in Northeastern China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, M.; Courtney, M.K.; Vergara, J.; McIntyre, D.; Nix, S.; Marion, A.; Shergill, G. Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact. Child Youth Care Forum 2021, 50, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chen, S. Associations of Time Spent on Study and Sleep with Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Junior High School Students: Report from the Large-Scale Monitoring of Basic Education Data in China. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2023, 25, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.H.; Tran, T.D.; Holton, S.; Nguyen, H.T.; Wolfe, R.; Fisher, J. Reliability, convergent validity and factor structure of the DASS-21 in a sample of Vietnamese adolescents. PLoS ONE 2017, 277, 110456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, P.J.; Zajac, I.T.; Venning, A.J. The structure of anxiety and depression in a normative sample of younger and older Australian adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Mill, J.G.; Vogelzangs, N.; Van Someren, E.J.W.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Sleep duration, but not insomnia, predicts the 2-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.; Anjum, A.; Uddin, M.E.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, M.F. Impacts of socio-cultural environment and lifestyle factors on the psychological health of university students in Bangladesh: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Insomnia, sleep duration, and risk of anxiety: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 155, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Cai, L.; Zeng, X.; Gui, Z.; Lai, L.; Tan, W.; Chen, Y. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and executive functions in Chinese school-aged children. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Langberg, J.M.; Byars, K.C. Advancing a Biopsychosocial and Contextual Model of Sleep in Adolescence: A Review and Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, A.; Dresch, F.; Martins, A.C.; Levandovski, R.M.; Adan, A.; Natale, V.; Martoni, M.; Hidalgo, M.P. The influence of school time on sleep patterns of children and adolescents. Sleep Med. 2016, 19, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Du, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Teopiz, K.M.; Shi, J.; Guo, L.; Lu, C.; McIntyre, R.S. The associations between sleep situations and mental health among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal study. Sleep Med. 2021, 82, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadie, A.; Shafto, M.; Leng, Y.; Kievit, R.A.; Cam-CAN. How are age-related differences in sleep quality associated with health outcomes? An epidemiological investigation in a UK cohort of 2406 adults. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Oh, K.S.; Shin, D.W.; Lim, W.J.; Jeon, S.W.; Kim, E.J.; Cho, S.J.; Shin, Y.C. The association of physical activity and sleep duration with incident anxiety symptoms: A cohort study of 134,957 Korean adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heissel, J.A.; Norris, S. Rise and shine: The effect of school start times on academic performance from childhood through puberty. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 53, 957–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, H.E.; O’Rourke, F.; Dahl, R.E.; Goldstein, T.R.; Rofey, D.L.; Forbes, E.E.; Shaw, D.S. Young adolescent sleep is associated with parental monitoring. Sleep Health 2019, 5, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Guerrero, M.D.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Barbeau, K.; Barbeau, K.; Birken, C.S.; Chaput, J.P.; Faulkner, G.; Janssen, I.; Madigan, S.; et al. Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabrowska-Galas, M.; Ptaszkowski, K.; Dabrowska, J. Physical activity level, insomnia and related impact in medical students in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Sun, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, S. Structural validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in Chinese undergraduate students. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappier, M.T.; Bartl-Wilson, L.; Shoop, T.; Borowski, S. Sleep quality and sleepiness among veterinary medical students over an academic year. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std.Dev. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 1592 | 11.535 | 1.618 | 7.833 | 15.583 |

| Female, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.448 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| Board at school, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.149 | 0.357 | 0 | 1 |

| Only child, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.137 | 0.344 | 0 | 1 |

| Rural hukou, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.915 | 0.280 | 0 | 1 |

| Family Characteristics | |||||

| Migrant father, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.576 | 0.494 | 0 | 1 |

| Migrant mother, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.253 | 0.435 | 0 | 1 |

| Father’s education level, 1 = high school or above | 1592 | 0.241 | 0.428 | 0 | 1 |

| Mother’s education level, 1 = high school or above | 1592 | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0 | 1 |

| Father age, years | 1592 | 41.094 | 6.149 | 23 | 71 |

| Mother age, years | 1592 | 38.279 | 5.769 | 21 | 66 |

| Divorced parents, 1 = yes | 1592 | 0.085 | 0.279 | 0 | 1 |

| Family asset index | 1590 | −0.015 | 1.239 | −2.241 | 2.909 |

| Time Usage on Extracurricular activities | |||||

| Screen time, minutes | 1591 | 23.578 | 32.547 | 0 | 180 |

| Sport time, minutes | 1591 | 13.301 | 21.504 | 0 | 130 |

| Read time, minutes | 1591 | 26.792 | 19.031 | 0 | 120 |

| Students Abilities | |||||

| Resilience (Total CD-RISC scores) | 1592 | 59.872 | 14.139 | 0 | 100 |

| Standardized math test score | 1591 | 0.012 1 | 0.959 | −4.016 | 1.902 |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std.Dev. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Patterns | |||||

| Sleep duration on weekdays, hours | 1589 | 9.049 | 1.050 | 5.170 | 13.000 |

| Sleep duration on weekends, hours | 1565 | 10.181 | 1.211 | 5.500 | 15.000 |

| Gain adequate sleep on weekdays, 1 = yes | 1589 | 0.717 | 0.450 | 0 | 1 |

| Gain adequate sleep on weekends, 1 = yes | 1565 | 0.928 | 0.258 | 0 | 1 |

| Bedtime on weekdays, o’clock 1 | 1591 | 21:00 | 0.803 | 18:00 | 24:00 |

| Bedtime on weekends, o’clock | 1590 | 21:30 | 0.929 | 18:00 | 1:00 |

| Sleep late on weekdays, 1 = yes | 1589 | 0.193 | 0.395 | 0 | 1 |

| Sleep late on weekends, 1 = yes | 1571 | 0.380 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 |

| Student Mental Health Risks | |||||

| Depression (1 = yes) 2 | 1592 | 0.327 | 0.469 | 0 | 1 |

| no depression symptoms | 1592 | 0.673 | |||

| mild | 1592 | 0.097 | |||

| moderate | 1592 | 0.143 | |||

| severe | 1592 | 0.051 | |||

| extremely severe | 1592 | 0.036 | |||

| Anxiety (1 = yes) | 1592 | 0.512 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| no anxiety symptoms | 1592 | 0.488 | |||

| mild | 1592 | 0.090 | |||

| moderate | 1592 | 0.187 | |||

| severe | 1592 | 0.099 | |||

| extremely severe | 1592 | 0.136 | |||

| Stress (1 = yes) | 1592 | 0.287 | 0.453 | 0 | 1 |

| no stress symptoms | 1592 | 0.713 | |||

| mild | 1592 | 0.114 | |||

| moderate | 1592 | 0.108 | |||

| severe | 1592 | 0.048 | |||

| extremely severe | 1592 | 0.017 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | Gain Adequate Sleep on Weekdays, 1 = Yes | Gain Adequate Sleep on Weekends, 1 = Yes | Go to Sleep Late on Weekdays, 1 = Yes | Go to Sleep Late on Weekends, 1 = Yes | ||||

| Mean | Diff. | Mean | Diff. | Mean | Diff. | Mean | Diff. | |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 0.721 | 0.006 | 0.957 | 0.052 *** | 0.196 | 0.006 | 0.365 | −0.028 |

| Male | 0.715 | 0.905 | 0.191 | 0.392 | ||||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≥12 | 0.458 | −0.439 *** | 0.907 | −0.037 *** | 0.077 | −0.196 *** | 0.190 | −0.322 *** |

| <12 | 0.897 | 0.944 | 0.273 | 0.512 | ||||

| Board at School | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.553 | −0.194 *** | 0.910 | −0.021 | 0.051 | −0.168 *** | 0.166 | −0.252 *** |

| No | 0.746 | 0.932 | 0.218 | 0.418 | ||||

| Extracurricular activities | ||||||||

| Screen Time Exceeds 1 h/Day | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.625 | −0.108 *** | 0.895 | −0.039 ** | 0.254 | 0.071 ** | 0.504 | 0.146 *** |

| No | 0.733 | 0.934 | 0.183 | 0.359 | ||||

| Family Characteristics | ||||||||

| Migrant Father | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.717 | 0 | 0.928 | −0.002 | 0.187 | −0.015 | 0.390 | 0.025 |

| No | 0.718 | 0.929 | 0.202 | 0.366 | ||||

| Migrant Mother | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.728 | 0.014 | 0.931 | 0.004 | 0.170 | −0.032 | 0.367 | −0.017 |

| No | 0.714 | 0.927 | 0.201 | 0.384 | ||||

| Father’s Education > 9 Years | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.755 | 0.049 | 0.936 | 0.009 | 0.261 | 0.089 *** | 0.481 | 0.133 *** |

| No | 0.706 | 0.926 | 0.172 | 0.348 | ||||

| Mother’s Education > 9 Years | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.801 | 0.098 *** | 0.928 | 0 | 0.277 | 0.098 *** | 0.566 | 0.218 *** |

| No | 0.703 | 0.928 | 0.179 | 0.349 | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASS Mild Depression | DASS Mild Anxiety | DASS Mild Stress | DASS Moderate Depression | DASS Moderate Anxiety | DASS Moderate Stress | |

| Adequate Sleep | −0.061 * | −0.074 ** | −0.036 | −0.088 *** | −0.062 * | −0.023 |

| (Weekdays) | (−1.974) | (−2.131) | (−0.996) | (−3.304) | (−1.960) | (−1.080) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 |

| adj. R2 | 0.108 | 0.069 | 0.038 | 0.111 | 0.095 | 0.029 |

| Adequate Sleep | 0.006 | −0.047 | −0.011 | −0.040 | −0.049 | −0.024 |

| (Weekends) | (0.111) | (−0.764) | (−0.237) | (−0.932) | (−0.810) | (−0.499) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 |

| adj. R2 | 0.105 | 0.068 | 0.036 | 0.105 | 0.091 | 0.031 |

| Sleep Duration | −0.049 *** | −0.038 | −0.015 | −0.060 *** | −0.040 * | −0.015 |

| (Weekdays) | (−3.341) | (−1.526) | (−0.741) | (−4.910) | (−1.716) | (−1.083) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 |

| adj. R2 | 0.110 | 0.069 | 0.037 | 0.115 | 0.096 | 0.030 |

| Sleep Duration | −0.008 | −0.001 | −0.005 | −0.010 | −0.003 | −0.004 |

| (Weekends) | (−0.814) | (−0.056) | (−0.478) | (−1.099) | (−0.251) | (−0.419) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 | 1563 |

| adj. R2 | 0.106 | 0.067 | 0.037 | 0.105 | 0.091 | 0.031 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASS Mild Depression | DASS Mild Anxiety | DASS Mild Stress | DASS Moderate Depression | DASS Moderate Anxiety | DASS Moderate Stress | |

| Going to Sleep Late | 0.049 ** | 0.046 | 0.061 * | 0.074 *** | 0.069 *** | 0.027 |

| (Weekdays) | (2.354) | (1.684) | (2.040) | (3.229) | (2.953) | (1.030) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 | 1586 |

| adj. R2 | 0.107 | 0.067 | 0.039 | 0.110 | 0.096 | 0.030 |

| Going to Sleep Late | 0.089 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.095 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.104 *** | 0.055 ** |

| (Weekends) | (3.236) | (3.338) | (3.709) | (2.871) | (4.491) | (2.597) |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1569 | 1569 | 1569 | 1569 | 1569 | 1569 |

| adj. R2 | 0.113 | 0.073 | 0.046 | 0.111 | 0.100 | 0.033 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASS Score (Depression) | DASS Score (Anxiety) | DASS Score (Stress) | ||||

| Sleep duration | −2.823 | −1.314 | −3.958 | |||

| (Weekdays) | (−1.067) | (−0.560) | (−1.478) | |||

| Sleep duration squared | 0.111 | 0.035 | 0.188 | |||

| (Weekdays) | (0.731) | (0.265) | (1.214) | |||

| Sleep duration | −3.120 | −3.863 ** | −5.896 *** | |||

| (Weekend) | (−1.408) | (−2.353) | (−3.174) | |||

| Sleep duration squared | 0.142 | 0.175 ** | 0.276 *** | |||

| (Weekend) | (1.382) | (2.256) | (3.116) | |||

| U-test (p-value) | 0.484 | 0.109 | - | 0.030 | 0.253 | 0.004 |

| Extreme point | 12.752 | 10.982 | - | 11.016 | 10.520 | 10.689 |

| Control Variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Class FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 1586 | 1563 | 1586 | 1563 | 1586 | 1563 |

| adj. R2 | 0.119 | 0.118 | 0.062 | 0.061 | 0.043 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lyu, J.; Jin, S.; Ji, C.; Yan, R.; Feng, C.; Rozelle, S.; Wang, H. The Connection between Sleep Patterns and Mental Health: Insights from Rural Chinese Students. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12151507

Lyu J, Jin S, Ji C, Yan R, Feng C, Rozelle S, Wang H. The Connection between Sleep Patterns and Mental Health: Insights from Rural Chinese Students. Healthcare. 2024; 12(15):1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12151507

Chicago/Turabian StyleLyu, Jiayang, Songqing Jin, Chen Ji, Ru Yan, Cindy Feng, Scott Rozelle, and Huan Wang. 2024. "The Connection between Sleep Patterns and Mental Health: Insights from Rural Chinese Students" Healthcare 12, no. 15: 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12151507

APA StyleLyu, J., Jin, S., Ji, C., Yan, R., Feng, C., Rozelle, S., & Wang, H. (2024). The Connection between Sleep Patterns and Mental Health: Insights from Rural Chinese Students. Healthcare, 12(15), 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12151507