Abstract

In the healthcare field, the effective implementation of clinical protocols is crucial to ensuring patient safety and well-being. In this context, this study evaluates nurses’ adherence to the maintenance and replacement protocol of peripheral venous catheters (PVCs) in a university hospital in Spain, examining the impact of compliance with the protocol on the loss of PVCs and on patient safety in addition to analyzing the related costs. A retrospective observational study was conducted with 590 patients who were admitted in 2018 and 2019. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was used to see the association between the study variables; with the dependent variable being the loss of PVCs (including, as a dependent variable, the loss of PVCs before 48 h). The patients’ electronic and physical medical records were reviewed to analyze nursing interventions related to the management of PVCs. A total of 24% of patients experienced PVC loss within the first 24 h after insertion. Failure to comply with the protocol resulted in 80% more catheter loss and increased the cost of cannulation by 46.84%. Low compliance with PVC care protocols significantly increases the risk of catheter loss, suggesting the need for increased training and strict protocol implementation. The findings emphasize the critical role of nursing in ensuring patient safety through adherence to evidence-based protocols. Continuing education and diligent protocol implementation are essential to reducing healthcare costs and improving patient outcomes.

Keywords:

adherence; NANDA-I; nursing interventions; patient safety; peripheral venous catheter; protocol; quality; cost 1. Introduction

In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the Global Patient Safety Alliance with the general aim of “Do No Harm” during health care, and, for this, it identified, as a common denominator, 10 lines of action for all participants of this Alliance [1]. The objective is to eliminate or reduce, to reasonable minimum levels, the preventable damage derived from patient care.

Despite healthcare having a significant impact on patient safety, the outcomes remain disheartening. According to the 2021 Prevalence Study of Nosocomial Infections (EPINE) in Spain, 1 in 10 hospitalized patients experience preventable harm, with at least 50% of these cases being avoidable [2].

In the context of nursing care, the insertion and maintenance of the peripheral venous catheter (PVC) and adherence to established protocols are crucial, constituting a routine part of nursing practice. It is crucial to consistently apply standard precautions in the management of PVCs, such as proper selection of the insertion site, maintenance of aseptic techniques during insertion, and constant monitoring of the insertion site to detect signs of infection or complications [1,3,4]. Most patients in emergency departments or hospital admissions receive a PVC. This is substantiated by the EPINE 2021 study, which indicates that 76.57% (of 49,836 patients) were fitted with a catheter [2].

Various studies and approaches exist regarding the protocols for insertion and maintenance of PVCs, yielding diverse outcomes. Estimates suggest that the incidence of phlebitis can range between 16% and 55% in the absence of preventive measures [1,3,4,5]. However, assessing patient safety costs during hospitalization, based on adherence to these protocols, offers a valuable tool for decision-making and healthcare system management. It is crucial to evaluate the actual impact of compliance with PVC management protocols on catheter loss and, consequently, on reducing potential harm and adverse effects to the patient, thereby enhancing patient safety. Also, we highlight the increase in costs. The loss of PVC implies added costs for its replacement, including materials and nursing time, increasing hospital spending [1,6]. To investigate this issue, the study aimed to assess the loss of adherence, by nurses, to the previously developed and implemented established protocol for PVC management and its subsequent impact on patient safety, in addition to analyzing the related costs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Configuration of the Study

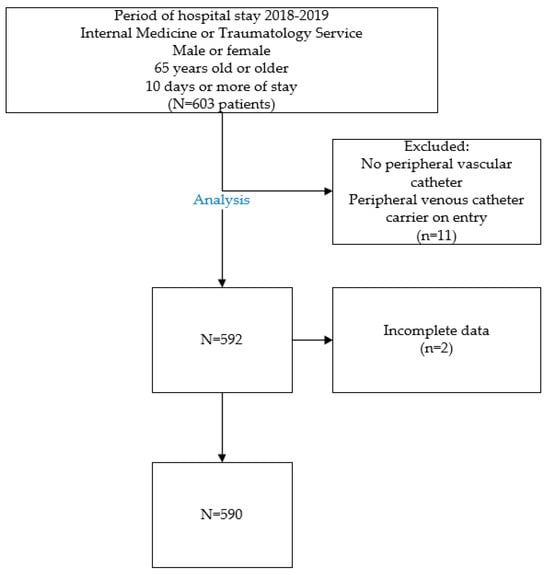

A retrospective observational descriptive study of 603 patients admitted to the HM Torrelodones University Hospital, in Madrid (Spain) was performed during the years 2018 and 2019, of which 11 patients were excluded, leaving a final sample of 590 patients.

2.2. Subjects

The study’s patient selection criteria included those admitted to HM Torrelodones University Hospital under Internal Medicine or Traumatology services, aged 65 years or older, of either male or female gender, with a median hospital stay of 10 days or more. Exclusion criteria encompassed patients without a peripheral venous catheter and those with catheters inserted at other hospitals or healthcare centers.

The flow of inclusion of patients in the study can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection of patients based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Development of PVC Care and Maintenance Protocol

An expert committee was established, comprising the Nursing Leadership, Nursing Supervisor of Hospitalization Units, and experienced nurses with over 5 years in various departments, including Emergency and Hospitalization. This committee formulated an action protocol based on the latest international standards from the Infusion Nurses Society (INS), good clinical practice guidelines by the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO), and recent scientific evidence-based recommendations [6,7,8,9,10].

The nursing protocol established guidelines for the maintenance and care of PVCs. The training of nurses was carried out through an information session explaining the established protocol and the subsequent addressing of any doubts about it. Following a training period for the nursing staff of hospitalization units and a testing phase to address any uncertainties and errors, the protocol’s implementation formally commenced on 1 January 2018. The protocol encompasses the following specific nursing interventions:

- Hand hygiene practices.

- Selecting the puncture area and gauge of the PVC (B.Braun Medical, S.A., Madrid, Spain)

- PVC insertion and securement using a protective or self-adhesive fabric patch.

- Disinfecting the puncture zone with aqueous chlorhexidine 2% (Bohm laboratories, Madrid, Spain)

- Documenting PVC gauge, insertion date, and shift.

- Changing the PVC protective patch at 72 h for acrylate-containing self-adhesive fabric patches, and at 144 h (6 days) for clear adhesive polyurethane patches, including puncture point care.

- Routine review and replacement of PVC every 144 h (6 days), according to the protocol.

- Reinitiating the protocol for PVC care and replacement intervals in case of PVC loss, regardless of the cause.

2.4. Variables

To assess the impact of adherence to the established protocol on peripheral venous catheter (PVC) loss, the study defined dependent variables and independent variables:

2.4.1. Independent Variables

- PVC Change Planning: Dichotomous qualitative assessment of whether the catheter change is scheduled at 144 h post-insertion.

- PVC Change Execution: Dichotomous qualitative measure of whether the PVC is actually replaced at 144 h post-insertion.

- Dressing Change Planning: Dichotomous qualitative evaluation of whether the dressing change is scheduled as per the protocol.

- Dressing Change Execution: Dichotomous qualitative assessment of whether the dressing is changed at either 72 or 144 h, depending on the dressing type.

2.4.2. Dependent Variable

Lost PVCs: Dichotomous qualitative measure, excluding cases where removal is due to medical direction or patient action, focusing on PVC loss due to extravasation, phlebitis, or accidental loss.

2.4.3. Control Variable

PVC Lost Before 48 Hours: Dichotomous qualitative assessment of PVC loss within 48 h of insertion. These data may indicate initial problems in the insertion and stabilization of the catheter.

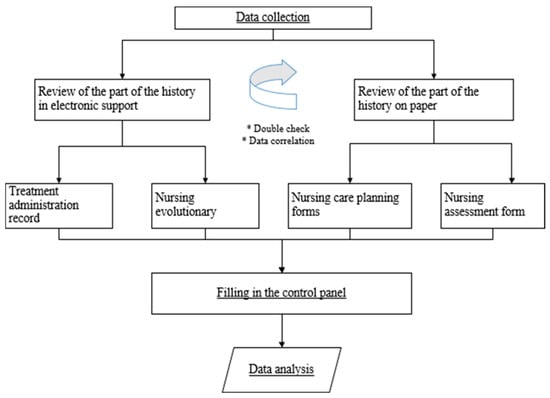

2.5. Data Collection Flow

The research team from the Quality Department of HM Hospitals Group was responsible for reviewing the medical records of study participants. To enhance the precision of the data collected and address inconsistencies in the completion of various records, the team utilized two distinct sources, ensuring comprehensive and reliable information, as can be seen in Figure 2 *.

Figure 2.

Data analysis. Description of the analysis flow and review of the data from the medical records in paper and computerized format.

This dual verification involved reviewing both nursing evolution and the signature records of treatment administration in the electronic medical records, as well as nursing assessment and care planning.

A dashboard was developed for recording the reviewed data. A skilled nursing team conducted the data analysis. This encompassed information such as PVC placement date, catheter change planning date, puncture site care, dressing change date, and documentation of executed interventions. Also included were details of PVC loss incidents (due to extravasation, infiltration, phlebitis, or accidental loss) if they occurred.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences International Business Machines IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 software (IBM Corporation USA, Armonk, NY, USA).

Descriptive statistics were performed by means of mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. Association between qualitative variables was carried out with the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, whichever was most suitable for each situation. Statistical significance was established with a p-value < 0.05.

2.7. Cost Estimation

The Interministerial Commission on Drug Prices establishes the costs of medical supplies [11]. The average cost of PVCs and the costs associated with patients in which the nursing staff complied with the established protocol as well as with those in which it was not complied with were calculated. The average cost of hospital stays in patients based on compliance with the protocol has been calculated. The total average cost refers to the cost of the PVC and stay of each of the patients segmented by the degree of adherence. Total costs of the analyzed procedures were estimated from the payer’s perspective, that is, including the direct healthcare costs associated with the hospital stay and the route change. The cost of the stay was calculated based on published data [12]. The consumed resources were obtained from the analytical accounting of HM Hospitals. This information comes from the Electronic Medical Records of the hospital group (Doctoris®), where health resources are charged by minimum consumption units and not by box units. The total cost is obtained by multiplying the number of resource units used by the unit cost. Direct health costs are obtained as the sum of all resources consumed in medical consultations, medical and diagnostic tests, medical material, medications, and resources consumed in surgical procedures. Incremental costs are estimated as the difference between the innovation and the standard considered technique [13]. The costs of materials and hospital stay is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Costs of materials used for PVC piping and costs of hospital stay.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data for the Study Participants

Baseline data for the study participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the patients included and sample percentage.

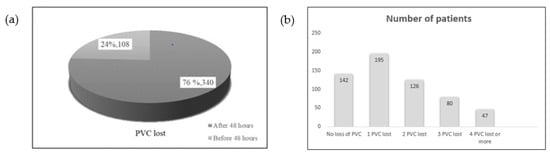

3.2. Analysis Based on the Degree of Adherence

Data from 590 patients who met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were analyzed. Among these, 75.93% (448 patients) experienced at least one loss of their PVC during hospitalization and 24.07% (142 patients) did not suffer any PVC loss. Notably, 24% (108 patients) lost their PVC within the first 48 h of placement, as detailed in Figure 3. Furthermore, 56.47% of patients with PVC loss experienced more than one catheter loss during their admission. The total number of PVCs removed due to non-permeability caused by phlebitis, infiltration, extravasation, or loss due to ineffective fixation was 875. The distribution of patients according to the number of lost PVCs is analyzed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Percentage of PVCs lost before 48 h and distribution of lost PVCs. (a) Number of PVCs, with respect to total, lost before and after 48 h from insertion, respectively. (b) Distribution by number of patients according to number of lost PVCs.

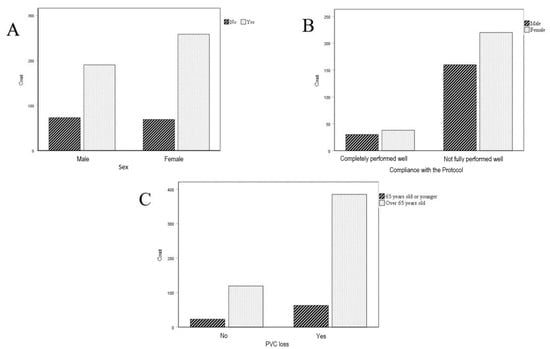

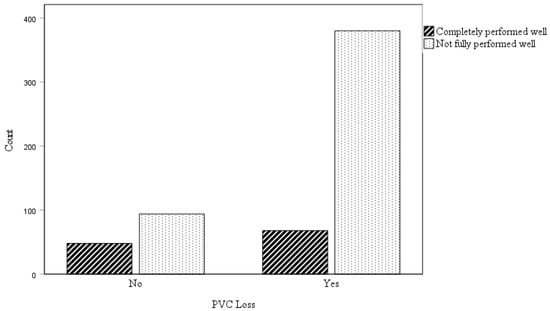

Among the 448 patients who experienced PVC loss, 190 were male and 258 were female. The loss rate for PVCs was 78.9% in women and 72.2% in men, with no significant gender difference based on the obtained p-value (0.060). Additionally, among those with PVC loss where the protocol was not fully followed, 42.1% (160) were male and 57.9% (220) were female. The p-value (0.757) indicates no significant gender difference in adherence to the protocol’s stipulations, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The analysis includes a comparative assessment of PVC loss by gender and across established age groups. It encompasses: (A) A comparison of PVC loss between female and male patients; (B) an analysis of adherence to PVC care and management protocols based on gender; (C) an evaluation of PVC loss in patients over 65 years of age versus those 65 years old or younger.

In the study sample, 85.9% (385 patients) of the patients who experienced PVC loss were over 65 years old, compared to 14.1% (63 patients) for those aged 65 or younger. However, the obtained p-value (0.530) suggests no significant difference in PVC loss between patients aged 65 or less and those older than 65, as illustrated in Figure 4.

In the patient sample, 88.8% were under the care of Internal Medicine, with 67% of these patients experiencing PVC loss. Among the 59 patients under Traumatology, 79.6% lost their peripheral venous catheter.

Table 3 presents the percentage of peripheral venous catheter loss in relation to adherence levels to PVC change and care protocols, along with their statistical significance. In patients from Internal Medicine, a significant correlation is observed between adherence to the protocol for line change, dressing change, and maintenance, and a reduced risk of PVC loss. However, in patients from Traumatology, such an association is not evident.

Table 3.

Percentage of PVC (peripheral venous catheter) loss depending on the degree of adherence to the PVC change protocol and p-value obtained. Percentage of PVC loss depending on the degree of adherence to the PVC dressing change and care protocol. Comparison of results as a function of adherence to the indications given.

In this study, protocol dictated PVC changes at 144 h post-placement. Out of the 590 patients in the sample, only 19.7% (116 patients) adhered to the guidelines, with 68 patients (15.2%) losing their catheter before 144 h. In 80.3% (474) of the patients in the sample, the nursing professional did not follow the established protocols for the care and maintenance of PVCs, resulting in 84.8% of these patients (380 patients) losing their PVCs, as indicated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of costs based on compliance or non-compliance with the PVC management protocols.

The p-value obtained (<0.05) reveals a statistically significant difference between patients who lost PVCs and adhered to the protocol versus those who lost PVCs and did not comply, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of PVC loss between patients who complied with the PVC management and care protocol and those who did not.

3.3. Cost Comparison Based on Adherence Level

Among the 590 patients in the study, 116 adhered to the protocol, and, of these, 68 patients experienced PVC loss, necessitating 125 new PVC insertions at a total cost of 2771.25 €. In contrast, for the 474 patients who did not follow the protocol, 750 new PVC cannulizations were required, costing 16,627.5 €. The average cost for PVC in patients non-compliant with the protocol was 46.84% higher.

In the study, patients who did not adhere to the PVC protocols accounted for 6423 hospital stays, in contrast to 1293 stays for those who followed the protocols. The average cost of hospital stays was 17.74% higher for patients who did not adhere to the protocols compared to those who did.

As indicated in Table 4, the average total cost for patients who did not adhere to the established protocols was 340.91 €, in comparison to 267.94 € for those who did comply with the protocol.

Table 5 and the data analyzed in this study reveal that the highest incidence of lost peripheral venous catheters (PVCs) occurs in hospital admissions ranging from 10 to 30 days, which also correspond to the periods with the highest number of hospital stays.

Table 5.

Relationship between hospital stay and lost PVCs depending on adherence or non-adherence to the established protocol.

4. Discussion

The main results obtained from this study are the following:

- In 80.3% (474) of the patients in the sample, the nursing professional did not follow the established protocols for the care and maintenance of PVCs, resulting in 84.8% of these patients (380 patients) losing their PVCs.

- A total of 75.93% of the patients who participated in the study lost at least one PVC, and 24% of these lost it before 48 h.

This study evaluated the effect of protocol adherence on catheter loss, including accidental loss, extravasation, infiltration, and phlebitis, in PVC care. Over 70% of patients, and up to 81% of those in internal medicine, use PVCs [2,14].

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend implementing effective strategies and thoroughly advocate for effective strategies and thorough documentation to ensure safe care and reduce adverse events. However, data on the impact of adherence to these standards is limited, as highlighted by the Venous Thromboembolism Zero Program. The ENEAS (2005) study further indicates that recommended practices are not fully implemented in hospitals, with the avoidability of adverse effects ranging from 50% to 70% [4,5,15].

The study underscores the significant impact of training, experience, and evidence-based practice by healthcare professionals on the incidence of adverse effects and complications related to PVC cannulation. It highlights the unacceptably high rate of PVC loss, impacting patient safety. The observed variability in care delivery underscores the lack of effective measures and evidence of compliance with and adherence to established recommendations and standards [5,6].

PVC loss occurred in 75% of cases, with phlebitis identified as one of the potential causes. This rate aligns with findings from other published studies but is higher than some reports which indicate PVC loss rates between 57.8% and 54.05% [15,16,17].

Phlebitis is recognized as the primary cause of catheter failure, with incidence rates ranging between 30.7% and 44% in various studies [18,19,20]. Despite some studies reporting lower phlebitis rates, all significantly exceed the 5% prevalence rate recommended by the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) [3,21]. The findings of this study indicate that 14% of PVC loss occurred within the first 24 h and 25% within 48 h. These figures are lower compared to other studies, which report PVC loss exceeding 55% within these time frames. The average duration of PVC usage noted in this research ranges between 2.5 to 4 days (60 to 96 h) [14,15,16,19,20,22].

While most studies indicate an average hospital stay of no more than 3.5 days, the specific risks and common complications beyond this period remain unclear [23]. Current standards and recommendations, including those for detecting microorganisms in case of infection, aim to ensure safe practice and promote a culture of safety, emphasizing daily monitoring to reduce adverse effects [6,7,24,25]. Studies have shown a significant difference in catheter failure rates within the first 38 h, decreasing over time, highlighting the importance of daily follow-up [6,7,16,24]. Adequate nurse training in the latest guidelines and scientific evidence is crucial, as is the implementation of standards [26]. Monitoring staff interventions is essential to ensuring adherence to standards and early complication detection [27]. Compliance with standards significantly impacts the PVC loss rate, potentially reducing it by up to 11% [28].

The study emphasizes that implementing best practice guidelines is crucial for risk management and reducing phlebitis rates [7,29,30,31]. The effectiveness of these guidelines’ implementation is a key factor. PVC loss significantly affects patient safety, potentially causing treatment delays, repeated cannulation pain, and increased costs and nursing time. In this study, 10.5% of patients required four or more new cannulations due to PVC loss, compared to other studies reporting up to 18.2% of patients needing five to nine cannulations for the same reason [31].

While some studies suggest an increased rate of catheter loss with clinically indicated removal versus routine replacement, numerous publications indicate no significant difference in PVC complications between the two methods [8,20,21,22,32,33,34]. More research is needed to understand the impact of these practices on bloodstream infection rates. Implementing and adhering to good practice guidelines for PVC management is essential to reducing bloodstream infections associated with PVC use [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Establishing concrete quality indicators for monitoring, along with maintaining training and evidence-based care, is crucial [40,42,43]. This study demonstrates the need for accurately recording nursing interventions, which in some cases were less than 50%. Such meticulous record keeping is vital for adequate follow-up in the care and maintenance of PVCs [34,44,45,46].

Designing effective training and reviewing adherence to standards based on current evidence is crucial, as is understanding nurse adherence rates to established protocols [34]. Deviations in nursing interventions, such as the use of transparent dressings or the daily review of puncture sites, have been noted [47]. This study’s findings align with these observations, revealing that in 68% of cases where PVCs were lost, the recommendations for follow-up and dressing change were not followed.

Formative intervention and training of nurses, coupled with ensuring their awareness of the latest scientific evidence, leads to better adherence to the most current guidelines. This approach results in a notable improvement in practices based on established evidence and adherence to set standards [48,49]. Adherence to protocols for PVC insertion varies across different hospital services. Despite similar rates of complications, varying factors in different services affect adherence, often leading to a failure in meeting patient safety principles and standards established by recent scientific evidence [6,7,14,45]. This study concludes that adherence to evidence-based standards significantly impacts PVC loss. While the results exceed INS guidelines, the emphasis is not solely on instructing best practices but also on implementing and monitoring these practices to identify and rectify deviations in deployment and compliance [6]. Based on this study’s findings, it is crucial to pay special attention to and further investigate the evolution and complications of PVCs between 96 and 144 h. Considering the average PVC duration ranges from 2.5 to 4 days, this research suggests the need for specific measures to reduce PVC loss and extend its average lifespan.

The lack of identification of the specific causes of PVC loss makes it difficult to implement effective preventive measures, and could be a line of research for future studies. In addition, possible staff turnover must be taken into account as well as the training and education of nurses adapted to PVC maintenance and care protocols.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant impact of protocol adherence on peripheral venous catheter loss and patient safety. It reveals that non-adherence to PVC care protocols leads to a higher rate of catheter loss and increased healthcare costs. The findings underscore the need for rigorous implementation and monitoring of established catheter care protocols, emphasizing the role of nursing in improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare expenses. These conclusions point towards the importance of ongoing education and protocol compliance in nursing practice to enhance patient safety. It is crucial to establish an integrated, continuous, in-service training program that withstands personnel fluctuations and ensures constant updating of knowledge and skills, as well as adherence to good practice protocols and guides.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.G., J.M.C.-R. and Á.A.-S.; Formal analysis, M.B.G., J.N.-A. and Á.A.-S.; Investigation, M.B.G.; Methodology, M.B.G. and Á.A.-S.; Software, J.M.C.-R.; Validation, M.B.G., J.T.R. and Á.A.-S.; Writing—original draft, M.B.G.; Writing—review & editing, M.B.G., J.M.C.-R. and Á.A.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was not supported by any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review of the study was approved by the Ethics Committee board of the HM Hospitals Group (CEIm) (Decision: 27 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results and findings of this study are available from the corresponding author. These data, due to confidentiality and ethical considerations, are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank HM Hospital and Universidad CEU San Pablo for providing the resources to carry out this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. World Alliance for Patient Safety: Forward Programme 2005. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43072 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- EPINE. Study the Prevalence of Infections (Healthcare-Related and Community-Acquired) and Antimicrobial Use in Acute Care Hospitals in Spain 2021. EPINE-EPPS Studio nº 31: 2021. Ministry of Health, Government of Spain; Spanish Society of Preventive Medicine, Public Health ang Hygiene. Madrid, Spain 2021. Available online: https://epine.es (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Martínez Ortega, C.; Suárez Mier, B.; Del Río Pisabarro, C.; Cantero, M.; Llinás, M. Zero Phlebitis Program; Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS): Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- National Study of Adverse Effects Linked to Hospitalization; ENEAS 2005; Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs: Madrid, Spain, 2006.

- Helm, R.E.; Klausner, J.D.; Klemperer, J.D.; Flint, L.M.; Huang, E. Accepted but Unacceptable: Peripheral IV Catheter Failure. J. Infus. Nurs. 2019, 42, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, L.A.; Hadaway, L.; Hagle, M.E.; Broadhurst, D.; Clare, S.; Kleidon, T.; Meyer, B.M.; Nickel, B.; Rowley, S.; Sharpe, E.; et al. Infusion Practice Standards Therapy, 8th Edition. J. Infus. Nurs. 2021, 44, S1–S224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). Vascular Access, 2nd ed.; RNAO: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Hu, Y.; Huang, X.; Fu, J.; Zhang, J. Clinically indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters in adults: A nonblinded, cluster-randomized trial in China. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 23, e12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Fernández, L.; Suérez-Mier, B.; Martínez-Ortega, M.D.C.; Lana, A. Incidence and risk factors of phlebitis associated to peripheral intravenous catheters. Enferm. Clin. 2017, 27, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattox, E.A. Complications of Peripheral Venous Access Devices: Prevention, Detection, and Recovery Strategies. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Council of Official Colleges of Pharmacists. Bot Plus Web (Internet Database). Available online: https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Bartra, A.; Caeiro, J.-R.; Mesa-Ramos, M.; Etxebarría-Foronda, I.; Montejo, J.; Carpintero, P.; Sorio-Vilela, F.; Gatell, S.; Canals, L. Cost of osteoporotic hip fracture in Spain by autonomous community. Span. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2019, 63, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Y.; Núñez-Alfonsel, J.; Ielpo, B.; Ferri, V.; Caruso, R.; Durán, H.; Díaz, E.; Malavé, L.; Fabra, I.; Pinna, E.; et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: A comparative cost-effectiveness study. Tech. Coloproctol. 2020, 2, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, C.; Collados-Gómez, L.; García-Manzanares, M.E.; Segura-Paz, A.M.; López-Gutierrez, A.M.; Pérez-García, S. Prospective cohort study on the management and complications of peripheral venous catheter in patients hospitalised in internal medicine. Span. Clin. J. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 221, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Gladfelter, T. Peripheral intravenous catheters in hospitalized patients: Practice, Dwell times, and factors impacting the dwell times: A single center retrospective study. J. Vasc. Access 2022, 23, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, X.; Yue, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Lin, Q.; Tan, Y.; Peng, S.Y.; Li, X.F. Catheter dwell time and risk of catheter failure in adult patients with peripheral venous catheters. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4488–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fan, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Su, Y. Risk factors for peripheral venous catheter failure: A prospective cohort study of 5345 patients. J. Vasc. Access 2022, 23, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zhang, J. The incidence and risk of infusion phlebitis with peripheral intravenous catheters: A meta-analysis. J. Vasc. Access 2020, 21, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, S.; Sen, S.; Cukurlu, D. Phlebitis-related peripheral venous catheterization and the associated risk factors. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simin, D.; Milutinović, D.; Turkulov, V.; Brkić, S. Incidence, severity and risk factors of peripheral intravenous cannula-induced complications: An observational prospective study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Kong, D.; Lyu, F.; Luan, L.; Yang, L. Incidence, risk factors and medical cost of peripheral intravenous catheter-related complications in hospitalised adult patients. J. Vasc. Access 2022, 23, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, L.M.; Parreira, P.M.; Oliveira, A.d.S.S.; Mónico, L.D.S.M.; Arreguy-Sena, C.; Henriques, M.A. Phlebitis and infiltration: Vascular trauma associated with the peripheral venous catheter. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2018, 26, e3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, S.G.; Green, A.K.; Hewitt, B.E.; Grace, S.A. Short Peripheral Catheter Dwell Time and Associated Complications: A Systematic Review. J. Infus. Nurs. 2020, 43, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safety in the Care of Hospitalized Patients; SENECA Project; Ministry of Health and Social Policy: Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- Aldea Mansilla, C.; Martínez-Alarcón, J.; Gracia Ahufinger, I.; Guembe Ramírez, M. Microbiological diagnosis of catheter-related infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 37, 668–672. [Google Scholar]

- Guanche-Sicilia, A.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B.; Castro-Peraza, M.E.; Rodríguez-Gómez, J.Á.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Duarte-Clíments, G. Prevention and Treatment of Phlebitis Secondary to the Insertion of a Peripheral Venous Catheter: A Scoping Review from a Nursing Perspective. Healthcare 2021, 9, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Shelly, M.; Nersinger, S.; Cai, X.; Olsan, T. Implementing Clinical Practice Guidelines for Replacing Peripheral Intravenous Catheters. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2020, 35, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollar, C. Optimizing the Effectiveness of Short Peripheral Catheters. J. Infus. Nurs. 2021, 44, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmar, A.; Guell, M.; Chaparro, J.; Grinspun, D. Implementation of good nursing practices: BPSO program as a main tool. Rev. Médica Clínica Condes 2018, 29, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz-Torres, M.; Corcuera Martínez, M.I.; Sancho Sena, E.; Aldonza-Torres, M.; Maali Centeno, S.; Martínez-Ortega, M.C.; Suárez-Mier, M.B. Randomized experimental study to evaluate the effectiveness of the Flebitis Zero project in Navarre. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2021, 44, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Catarino, F.; Lourenço, C.; Correia, C.; Dória, J.; Dixe, M.; Santos, C.; Sousa, J.; Mendonça, S.; Cardoso, D.; Costeira, C.R. Nursing Care in Peripheral Intravenous Catheter (PIVC): Protocol of a Best Practice Implementation Project. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yang, Q.; Nor, H.M.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xin, X.; Feng, A.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. The safety of clinically indicated replacement or routine replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters: A randomized controlled study. J. Vasc. Access 2022, 23, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Osborne, S.; Rickard, C.M.; Marsh, N. Clinically-indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Mavillard, I.; Parra-García, G.; Fernández-Fernández, I.; Rodríguez-Calero, M.Á.; Personat-Labrador, C.; Castro Sánchez, E. Care of peripheral intravenous catheters in three hospitals in Spain: Mapping clinical outcomes and implementation of clinical practice guidelines. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buetti, N.; Abbas, M.; Pittet, D.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; Teixeira, D.; Chraiti, M.; Sauvan, V.; Sauser, J.; Harbarth, S.; Zingg, W. Comparison of Routine Replacement with Clinically Indicated Replacement of Peripheral Intravenous Catheters. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Lai, C.; Wei, Y. Comparison of clinically indicated replacement and routine replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 964096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D. To Replace or Not to Replace? Replacing Short Peripheral Catheters Based on Clinical Indication. J. Infus. Nurs. 2019, 42, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendramim, P.; Avelar, A.F.M.; Rickard, C.M.; Pedreira, M.d.L.G. The RESPECT trial–Replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters according to clinical reasons or every 96 hours: A randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 107, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ding, Y.; Lu, Q.; Jin, S.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Lyu, Y.; Lin, F. Routine replacement versus replacement as clinical indicated of peripheral intravenous catheters: A multisite randomised controlled trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2959–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Víctor, D.R.; Ider Bat-Erdene Gupta, D.; Rajhans, P.; Sheila, N.M.; Muralidharan, S.; Mehta, Y.; Rai, V.; Hung, N.V.; Luxsuwong, M.; Tapang, A.R.D.; et al. Six-year study on peripheral venous catheter–associated BSI rates in 262 ICUs in eight countries of South-East Asia: International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium findings. J. Vasc. Access 2021, 22, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Vivas, S.; Micó-Esparza, J.; García-Abad, I.; Hevilla-Cucarella, E.; Ballestar-Tarin, M.; Blasco, J.; García-Molina, P. Training, management, and quality of nursing care of vascular access in adult patients: The INCATIV project. J. Vasc. Access 2021, 24, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Mavillard, I.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; De Pedro-Gómez, J.E.; Moya-Suarez, A.B.; Parra-Garcia, G.; Rodríguez-Calero, M.Á.; Castro-Sánchez, E. Implementation of a knowledge mobilization model to prevent peripheral venous catheter-related adverse events: PREBACP study-a multicenter cluster-randomized trial protocol. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høvik, L.H.; Gjeilo, K.H.; Lydersen, S.; Solligård, E.; Damås, J.K.; Gustad, L.T. Use of peripheral venous catheters in two Norwegian hospitals. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro-Oliveira, A.d.S.; Basto, M.L.; Braga, L.M.; Arreguy-Sena, C.; Melo, M.N.; Parreira, P.M.d.S.D. Nursing practices in peripheral venous catheter: Phlebitis and patient safety. Text Contexto Enferm. 2019, 28, e20180109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, M.M.M.; Khonji, L.M.A.; Gabr, W.F.M. Changes in nurses’ knowledge and clinical practice in managing local IV complications following an education intervention. Br. J. Nurs. 2022, 31, S24–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.; Milner, K.A.; Trudeau, J. Routine Versus Clinically Indicated Short Peripheral Catheter Replacement: An Evidence-based Practice Project. J. Infus. Nurs. 2018, 41, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Tella, S.; ALogan, P.; Khakurel, J.; Vizcaya-Moreno, F. Nurses’ Adherence to Patient Safety Principles: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, N.P.; Alexander, M.; Burns, L.A.; Dellinger, E.P.; Garland, J.; Heard, S.O.; Lipsett, P.A.; Masur, H.; Mermel, L.A.; Pearson, M.L.; et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-related Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e162–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.; Winchester, K.; Principe, R.B.; Culverwell, E. Prevalence of peripheral intravenous catheters and policy adherence: A point prevalence in a tertiary care university hospital. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).