Social Determinants of Health and Long-Term Mortality of Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Is There an Association?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feghali, J.; Yang, W.; Huang, J. Updates in Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Epidemiology, Etiology, Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Outcome. World Neurosurg. 2020, 141, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uno, M. Chronic Subdural Hematoma-Evolution of Etiology and Surgical Treatment. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2023, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, L.B.; Braxton, E.; Hobbs, J.; Quigley, M.R. Chronic subdural hematoma in the elderly: Not a benign disease. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 114, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhala, M.; Helen, P.; Seppa, K.; Huhtala, H.; Iverson, G.L.; Niskakangas, T.; Ohman, J.; Luoto, T.M. Long-term excess mortality after chronic subdural hematoma. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 162, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, T.M.; Rughani, A.I.; Goeckes, T.; Tranmer, B.I. Chronic subdural hematoma: A sentinel health event. World Neurosurg. 2013, 80, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. The Dahlgren-Whitehead model of health determinants: 30 years on and still chasing rainbows. Public Health 2021, 199, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M. A health map for the local human habitat. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2006, 126, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjelković Apostolović, M.; Stojanović, M.; Bogdanović, D.; Apostolović, B.; Milošević, Z.; Ignjatović, A. The trend of the quality of cause-of-death data and its association with socio-economic indicators in Serbia in the period 2005–19. Longit. Life Course Stud. 2024, 15, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rauhala, M.; Helen, P.; Huhtala, H.; Heikkila, P.; Iverson, G.L.; Niskakangas, T.; Ohman, J.; Luoto, T.M. Chronic subdural hematoma-incidence, complications, and financial impact. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 162, 2033–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Huang, J. Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Epidemiology and Natural History. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 28, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, K.; Helland, C.A. How often do chronic extra-cerebral haematomas occur in patients with intracranial arachnoid cysts? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.S.; Shim, J.J.; Yoon, S.M.; Lee, K.S. Influence of Gender on Occurrence of Chronic Subdural Hematoma; Is It an Effect of Cranial Asymmetry? Korean J. Neurotrauma 2014, 10, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechli, H.; Nordmann, A.; Bucher, H.C.; Gratzl, O. Demographics and prevalent risk factors of chronic subdural haematoma: Results of a large single-center cohort study. Neurosurg. Rev. 2004, 27, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Ding, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z. Risk factors for the development of chronic subdural hematoma in patients with subdural hygroma. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlmann, E.; Giorgi-Coll, S.; Whitfield, P.C.; Carpenter, K.L.H.; Hutchinson, P.J. Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: Inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liliang, P.C.; Tsai, Y.D.; Liang, C.L.; Lee, T.C.; Chen, H.J. Chronic subdural haematoma in young and extremely aged adults: A comparative study of two age groups. Injury 2002, 33, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cho, J.-H.; Goh, D.-H.; Kang, D.-H.; Shin, I.H.; Hamm, I.-S. Postoperative subdural hygroma and chronic subdural hematoma after unruptured aneurysm surgery: Age, sex, and aneurysm location as independent risk factors. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Fan, W.; Yu, X.; Wu, L.; Liu, W. A Single-Center Analysis of Sex Differences in Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma in China. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 888526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, K.; Sorimachi, T.; Honda, Y.; Matsumae, M. Chronic Subdural Hematoma in Women. World Neurosurg. 2017, 105, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, C.; Gu, J.; Weng, W.; Hui, J.; Mao, Q.; Gao, G.; Feng, J. Risk factors of hospital mortality in chronic subdural hematoma: A retrospective analysis of 1117 patients, a single institute experience. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 67, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Suilleabhain, P.S.; Gallagher, S.; Steptoe, A. Loneliness, Living Alone, and All-Cause Mortality: The Role of Emotional and Social Loneliness in the Elderly During 19 Years of Follow-Up. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.C.; Xie, W.; Lundberg, D.J.; Glei, D.A.; Weinstein, M.A. Loneliness, social isolation, and all-cause mortality in the United States. SSM-Mental Health 2021, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koso, R.E.; Sheets, C.; Richardson, W.J.; Galanos, A.N. Hip Fracture in the Elderly Patients: A Sentinel Event. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2018, 35, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, W.; Szapiro, N.; Heisler, T.; Krasner, M.I. Sentinel health events as indicators of unmet needs. Soc. Sci. Med. (1982) 1989, 29, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Health Determinants | Preoperative Neurological Status | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological Deficit | Headache | MGS 1 | ||||||||

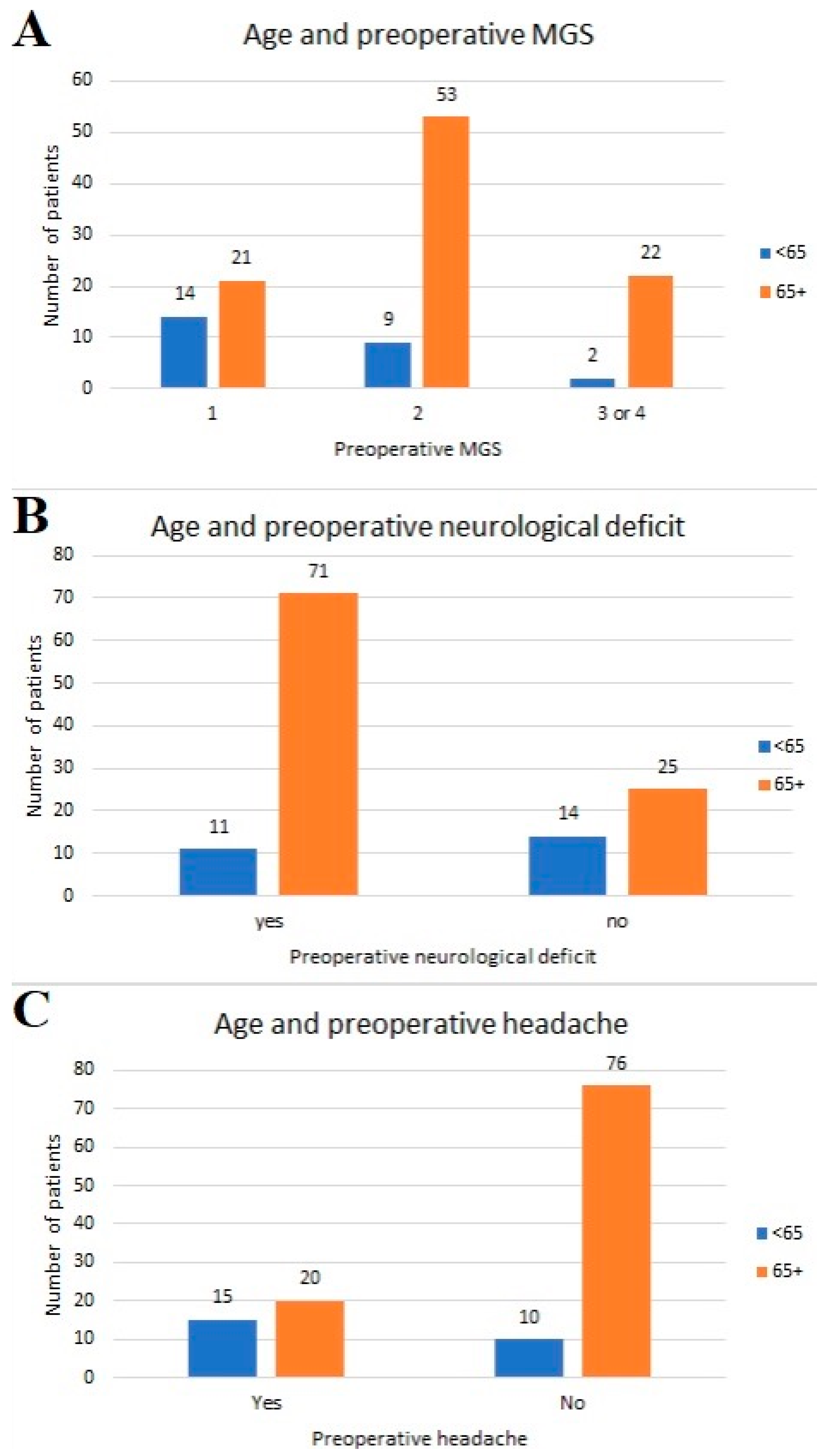

| (n = 121) | Yes | No | p Value | Yes | No | p Value | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | p Value |

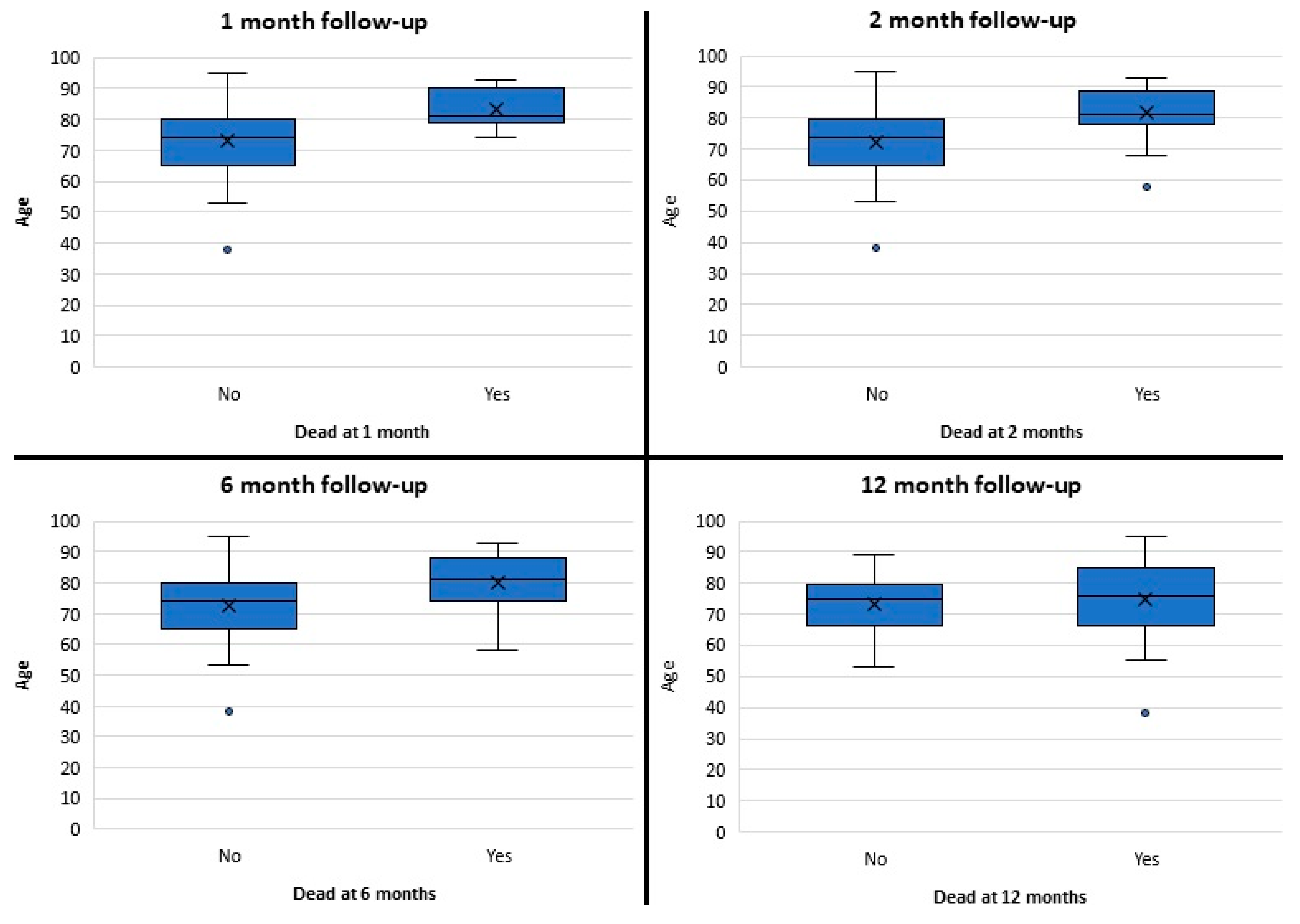

| Age | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| <65 years | 11 | 14 | 15 | 10 | 14 | 9 | 2 | |||

| >65 years | 71 | 25 | 20 | 76 | 21 | 53 | 22 | |||

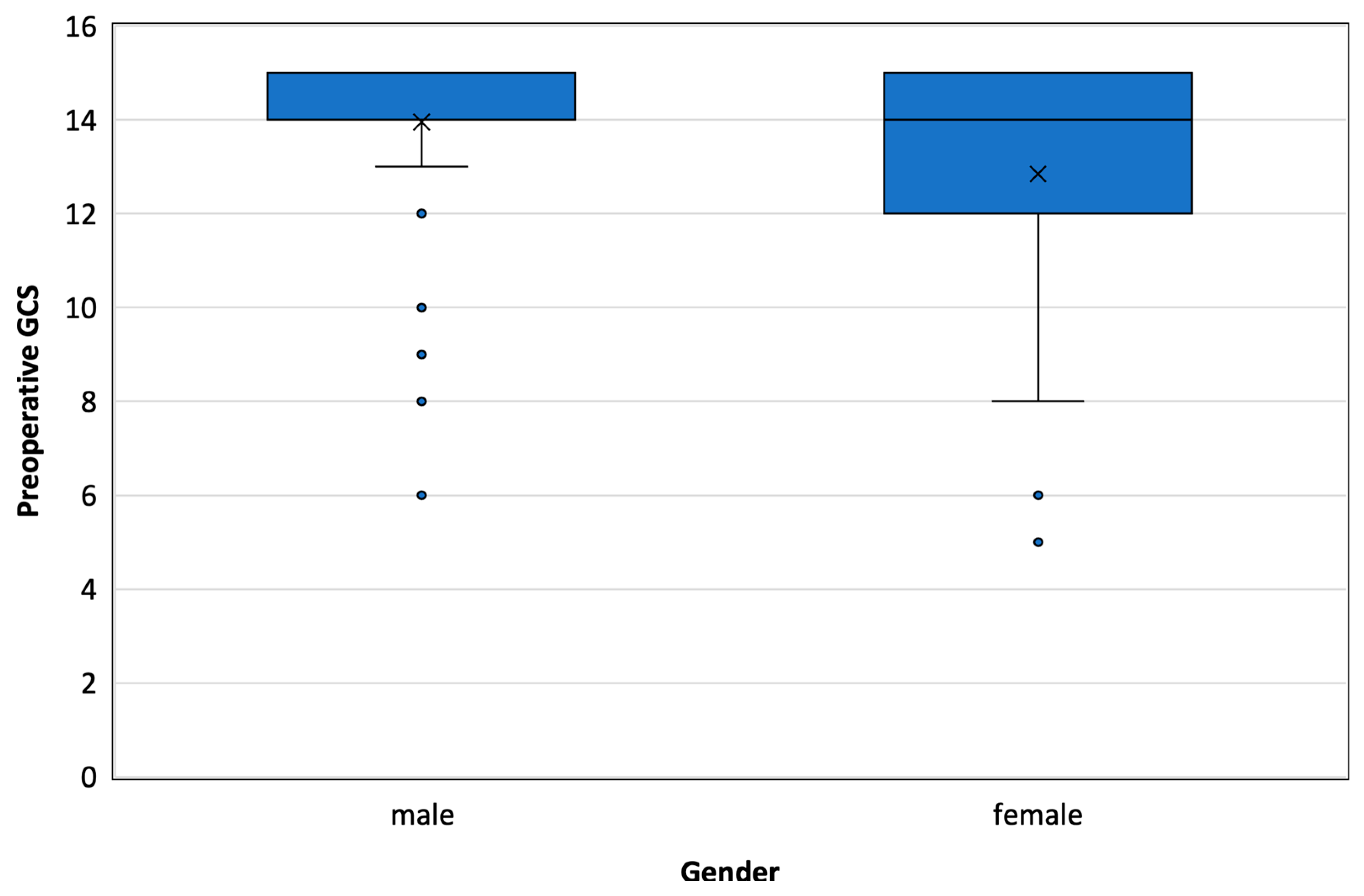

| Gender | 0.874 | 0.487 | 0.432 | |||||||

| Male | 60 | 28 | 27 | 61 | 27 | 46 | 15 | |||

| Female | 22 | 11 | 8 | 25 | 8 | 16 | 9 | |||

| Place of residence | 0.325 | 0.022 | 0.908 | |||||||

| Urban | 68 | 35 | 34 | 69 | 30 | 52 | 21 | |||

| Rural | 14 | 4 | 1 | 17 | 5 | 10 | 3 | |||

| Presence of associated disease | 0.124 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Yes | 72 | 30 | 20 | 82 | 23 | 57 | 22 | |||

| No | 30 | 9 | 15 | 4 | 12 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Living alone | 0.027 | 0.216 | 0.067 | |||||||

| Yes | 57 | 19 | 19 | 57 | 20 | 36 | 20 | |||

| No | 25 | 20 | 16 | 29 | 15 | 26 | 4 | |||

| Health insurance | 0.537 | 0.977 | 0.456 | |||||||

| Civil | 67 | 30 | 28 | 69 | 30 | 47 | 20 | |||

| Military | 15 | 9 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 15 | 4 | |||

| Work status | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Employed | 9 | 13 | 14 | 8 | 13 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Retired | 73 | 26 | 21 | 78 | 22 | 54 | 23 | |||

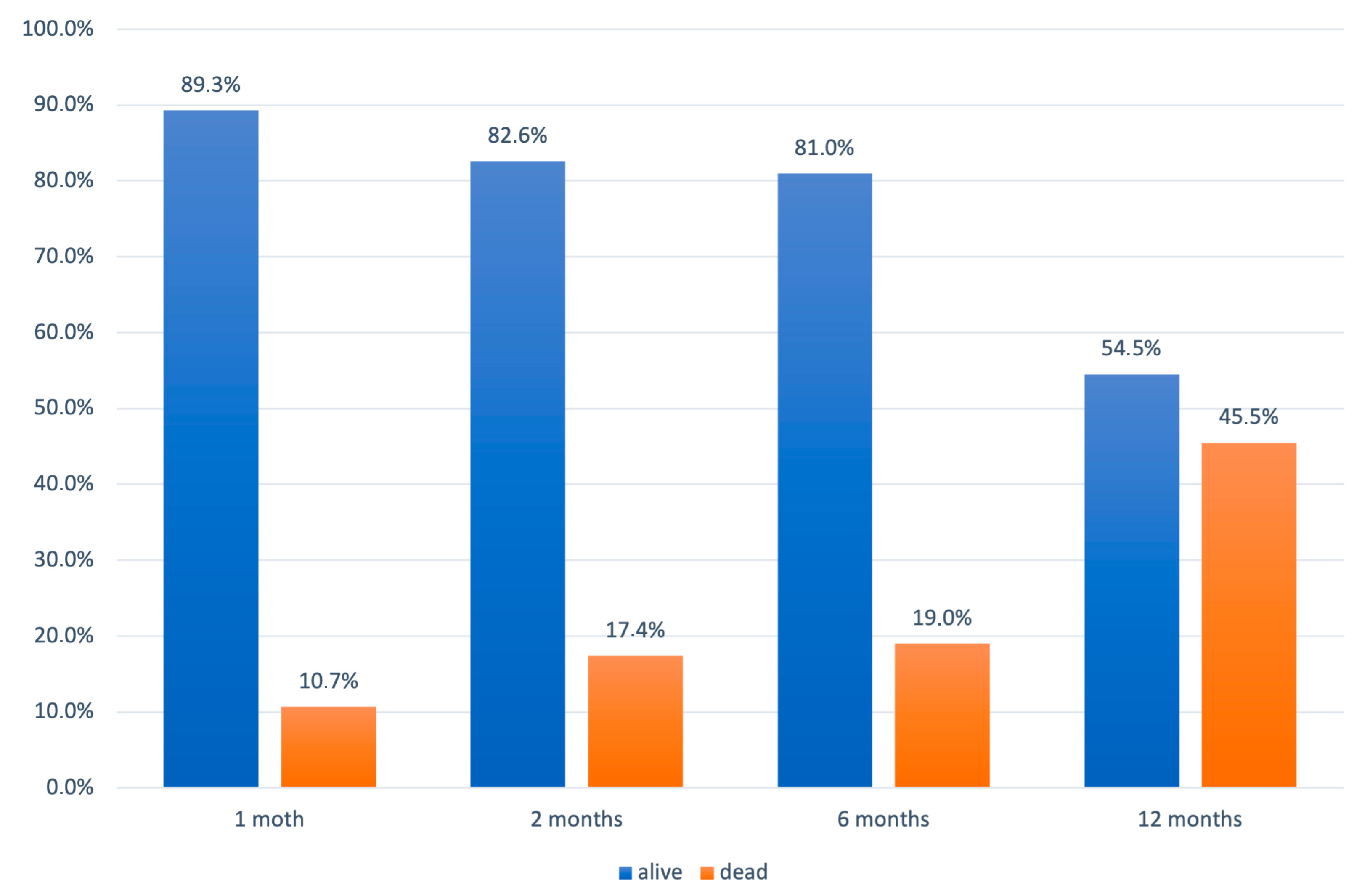

| N of Patients = 121 | Total | 1 Month | 2 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | Total Mortality (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Dead | Mortality (%) | Alive | Dead | Mortality (%) | Alive | Dead | Mortality (%) | Alive | Dead | Mortality (%) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 88 | 78 | 10 | 10 (24%) | 71 | 17 | 7 (17%) | 71 | 17 | / | 46 | 42 | 25 (60%) | 42 (47%) |

| Female | 33 | 30 | 3 | 3 (23%) | 29 | 4 | 1 (8%) | 27 | 6 | 2 (15%) | 20 | 13 | 7 (54%) | 13 (39%) | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 103 | 93 | 10 | 10 (21%) | 86 | 17 | 7 (15%) | 84 | 19 | 2 (4%) | 56 | 47 | 28 (60%) | 47 (42%) |

| Rural | 18 | 15 | 3 | 3 (38%) | 14 | 4 | 1 (13%) | 14 | 4 | / | 10 | 8 | 4 (50%) | 8 (44%) | |

| Work status | Employed | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0 (0%) | 21 | 1 | 1 (11%) | 20 | 2 | 1 (11%) | 13 | 9 | 7 (78%) | 9 (41%) |

| Retired | 99 | 86 | 13 | 13 (28%) | 79 | 20 | 7 (15%) | 78 | 21 | 1 (2%) | 53 | 46 | 25 (54%) | 46 (46%) | |

| Insurance | Civil | 97 | 88 | 9 | 9 (20%) | 80 | 17 | 8 (18%) | 78 | 19 | 2 (4%) | 52 | 45 | 26 (58%) | 45 (46%) |

| Military | 24 | 20 | 4 | 4 (40%) | 20 | 4 | / | 20 | 4 | / | 14 | 10 | 6 (60%) | 10 (42%) | |

| Associated diseases | Yes | 102 | 89 | 13 | 13 (27%) | 81 | 21 | 8 (16%) | 79 | 23 | 2 (4%) | 53 | 49 | 26 (53%) | 49 (48%) |

| No | 19 | 19 | 0 | / | 19 | 0 | / | 19 | 0 | / | 13 | 6 | 6 (100%) | 6 (32%) | |

| Alcohol abuse or dementia | Yes | 17 | 11 | 6 | 6 (100%) | 11 | 6 | / | 11 | 6 | / | 11 | 6 | / | 6 (35%) |

| No | 104 | 97 | 7 | 7 (14%) | 89 | 15 | 8 (16%) | 87 | 17 | 2 (4%) | 55 | 49 | 32 (65%) | 49 (47%) | |

| Living | Alone | 76 | 67 | 9 | 9 (21%) | 60 | 16 | 7 (17%) | 59 | 17 | 1 (2%) | 42 | 34 | 25 (60%) | 42 (55%) |

| With someone | 45 | 41 | 4 | 4 (31%) | 40 | 5 | 1 (8%) | 39 | 6 | 1 (8%) | 42 | 13 | 7 (54%) | 13 (29%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lepić, S.; Mićić, A.; Lepić, M.; Rasulić, L.; Mandić-Rajčević, S. Social Determinants of Health and Long-Term Mortality of Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Is There an Association? Healthcare 2024, 12, 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161627

Lepić S, Mićić A, Lepić M, Rasulić L, Mandić-Rajčević S. Social Determinants of Health and Long-Term Mortality of Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Is There an Association? Healthcare. 2024; 12(16):1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161627

Chicago/Turabian StyleLepić, Sanja, Aleksa Mićić, Milan Lepić, Lukas Rasulić, and Stefan Mandić-Rajčević. 2024. "Social Determinants of Health and Long-Term Mortality of Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Is There an Association?" Healthcare 12, no. 16: 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161627

APA StyleLepić, S., Mićić, A., Lepić, M., Rasulić, L., & Mandić-Rajčević, S. (2024). Social Determinants of Health and Long-Term Mortality of Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Is There an Association? Healthcare, 12(16), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161627