Foot Anthropometry Measures in Relation to Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

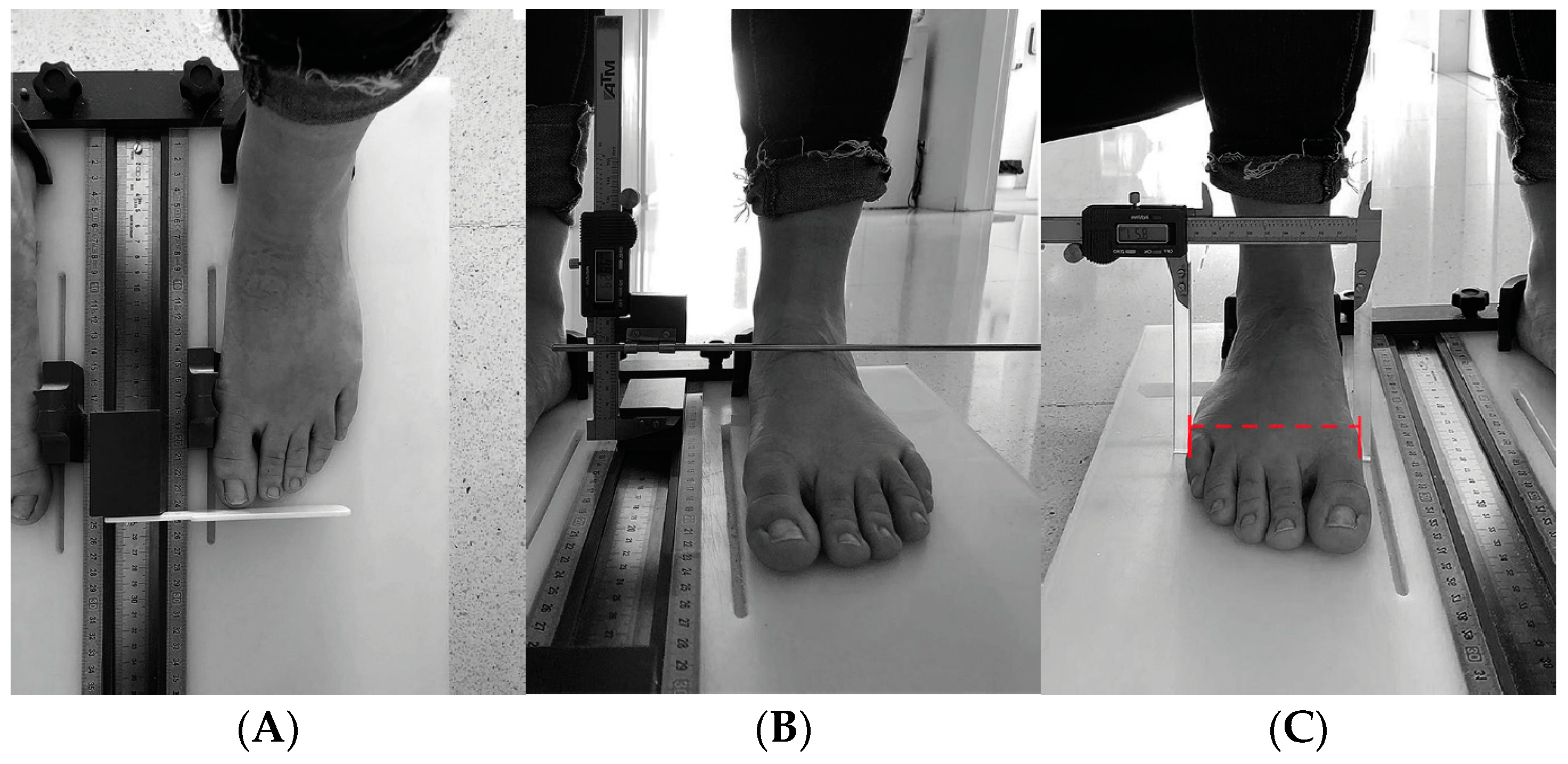

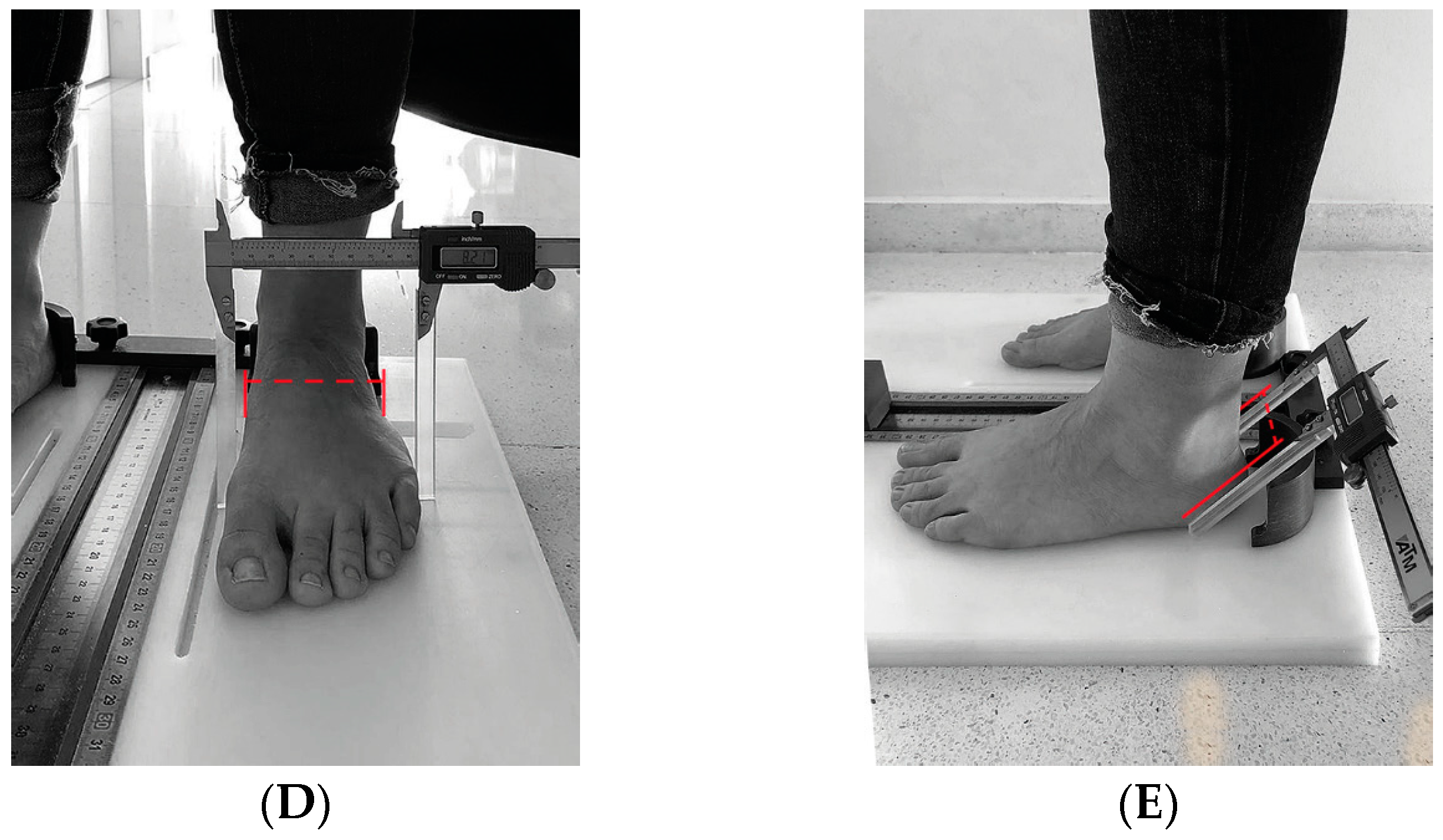

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nieves, A.T.; Holguera, R.M.; Gómez, A.P.; de Mon-Soto, M. Artritis reumatoide. Medicine 2017, 12, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, K.; Sharif, A.; Jumah, F.; Oskouian, R.; Tubbs, R.S. Rheumatoid arthritis in review: Clinical, anatomical, cellular and molecular points of view. Clin. Anat. 2018, 31, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourilovitch, M.; Galarza-Maldonado, C.; Ortiz-Prado, E. Diagnosis and classification of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 2014, 48–49, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinoso-Cobo, A.; Gijon-Nogueron, G.; Caliz-Caliz, R.; Ferrer-Gonzalez, M.A.; Vallejo-Velazquez, M.T.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Ortega-Avila, A.B. Foot health and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munchey, R.; Pongmesa, T. Health-Related Quality of Life and Functional Ability of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Study from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Thailand. Value Health Reg. Issues 2018, 15, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuidema, R.; Repping-Wuts, H.; Evers, A.; Van Gaal, B.; Van Achterberg, T. What do we know about rheumatoid arthritis patients’ support needs for self-management? A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiegel, A.; Rosenbaum, D.; Schorat, A.; Hilker, A.; Gaubitz, M. Assessment of foot impairment in rheumatoid arthritis patients by dynamic pedobarography. Gait Posture 2008, 27, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, K.; Ikari, K.; Inoue, E.; Sakuma, Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Koenuma, N.; Tobimatsu, H.; Tanaka, E.; Taniguchi, A.; Okazaki, K.; et al. Features of patients with rheumatoid arthritis whose debut joint is a foot or ankle joint: A 5479-case study from the IORRA cohort. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Xiao, H.; Li, E.; Ke, H.; Yang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z. Effect of solution-focused approach on anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A quasi-experimental study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 939586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, D.T.; Jackson, G.E.; Geary, N.P. The rheumatoid foot and ankle: Current evidence. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012, 18, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, F.; Hariharan, K. The rheumatoid forefoot. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2013, 6, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt, M.; Suhonen, R.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Foot health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis—A scoping review. Rheumatol. Int. 2017, 37, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Chang, S.H. Prevalence of feet and ankle arthritis and their impact on clinical indices in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome, K.; Gow, P.J.; Dalbeth, N.; Chapman, J.M. Clinical audit of foot problems in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated at Counties Manukau District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2009, 2, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, P. Foot Problems in a Group of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Unmet Need for Foot Care. Open Rheumatol. J. 2012, 6, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Leeden, M.; Steultjens, M.P.M.; Terwee, C.B.; Rosenbaum, D.; Turner, D.; Woodburn, J.; Dekker, J. A systematic review of instruments measuring foot function, foot pain, and foot-related disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2008, 59, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, T.; Nakano, H.; Homan, K.; Kondo, E.; Iwasaki, N. Preoperative radiographic and clinical factors associated with postoperative floating of the lesser toes after resection arthroplasty for rheumatoid forefoot deformity. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazzam, M.; Long, J.T.; Marks, R.M.; Harris, G.F. Kinematic changes of the foot and ankle in patients with systemic rheumatoid arthritis and forefoot deformity. J. Orthop. Res. 2007, 25, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Helliwell, P.; Siegel, K.L.; Woodburn, J. Biomechanics of the foot in rheumatoid arthritis: Identifying abnormal function and the factors associated with localised disease ‘impact’. Clin. Biomech. 2008, 23, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.E.; Woodburn, J.; Helliwell, P.S.; Cornwall, M.W.; Emery, P. Pes planovalgus in RA: A descriptive and analytical study of foot function determined by gait analysis. Musculoskelet. Care 2003, 1, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubbeldam, R.; Baan, H.; Nene, A.V.; Drossaers-Bakker, K.W.; van de Laar, M.A.F.J.; Hermens, H.J.; Buurke, J.H. Foot and ankle kinematics in rheumatoid arthritis: Influence of foot and ankle joint and leg tendon pathologies. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiegel, A.; Vieth, V.; Gaubitz, M.; Rosenbaum, D. Pedography and radiographic imaging for the detection of foot deformities in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Biomech. 2008, 23, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radner, H.; Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis:Benefit over low disease activity in patient-reported outcomes and costs. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014, 16, R56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuijper, T.M.; Lamers-Karnebeek, F.B.; Jacobs, J.W.; Hazes, J.M.; Luime, J.J. Flare Rate in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Low Disease Activity or Remission When Tapering or Stopping Synthetic or Biologic DMARD: A Systematic Review. J. Rheumatol. 2015, 42, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Castillo, J.A.; Reinoso-Cobo, A.; Gijon-Nogueron, G.; Caliz-Caliz, R.; Exposito-Ruiz, M.; Ramos-Petersen, L.; Ortega-Avila, A.B. Symmetry Criterion for Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Foot: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Leeden, M.; Steultjens, M.P.; van Schaardenburg, D.; Dekker, J. Forefoot disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients in remission: Results of a cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, R3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPoil, T.G.; Vicenzino, B.; Cornwall, M.W.; Collins, N. Can foot anthropometric measurements predict dynamic plantar surface contact area? J. Foot Ankle Res. 2009, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscontini, D.; Bocci, E.B.; Gerli, R. Analysis of foot structural damage in rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical evaluation by validated measures and serological correlations. Reumatismo 2009, 61, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuryliszyn-Moskal, A.; Kaniewska, K.; Dzięcioł-Anikiej, Z.; Klimiuk, P.A. Evaluation of foot static disturbances in patients with rheumatic diseases. Reumatologia 2017, 55, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Turner, D.E.; Woodburn, J. Characterising the clinical and biomechanical features of severely deformed feet in rheumatoid arthritis. Gait Posture 2008, 28, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantalaiho, V.; Kautiainen, H.; Korpela, M.; Hannonen, P.; Kaipiainen-Seppänen, O.; Möttönen, T.; Kauppi, M.; Karjalainen, A.; Laiho, K.; Laasonen, L.; et al. Targeted treatment with a combination of traditional DMARDs produces excellent clinical and radiographic long-term outcomes in early rheumatoid arthritis regardless of initial infliximab. The 5-year follow-up results of a randomised clinical trial, the NEO-RACo trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, T.; Hirao, M.; Tsuji, S.; Ebina, K.; Tsuboi, H.; Etani, Y.; Akita, S.; Hashimoto, J. Association of Decreased Physical Activity with Rheumatoid Mid-Hindfoot Deformity/Destruction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakubo, Y.; Wanezaki, Y.; Oki, H.; Naganuma, Y.; Shibuya, J.; Honma, R.; Suzuki, A.; Satake, H.; Takagi, M. Forefoot Deformities in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Mid- to Long-Term Result of Joint-Preserving Surgery in Comparison with Resection Arthroplasty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodburn, J.; Helliwell, P.S. Foot problems in rheumatology. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1997, 36, 932–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scott, D.L.; Wolfe, F.; Huizinga, T.W.J. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010, 376, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermoso, R.B.; Lozano, M.R.M.; Cordero, M.N.; Rincón, C.M.; García-Fernández, P.; Fernández, M.L.G. Differences and Similarities in the Feet of Metatarsalgia Patients with and without Rheumatoid Arthritis in Remission. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Petersen, L.; Nester, C.J.; Reinoso-Cobo, A.; Nieto-Gil, P.; Ortega-Avila, A.B.; Gijon-Nogueron, G. A Systematic Review to Identify the Effects of Biologics in the Feet of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medicina 2020, 57, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina-Bueno, M.; Munuera-Martínez, P.V.; Pérez-García, S.; Vázquez-Bautista, M.d.C.; Domínguez-Maldonado, G.; Palomo-Toucedo, I.C. Foot Pain and Morphofunctional Foot Disorders in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2018 | 2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | CI 95% | SD | Mean | CI 95% | SD | |||

| Age (years) | 56.59 | 54.47 | 58.72 | 10.87 | 61.88 | 59.74 | 64.03 | 10.97 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.92 | 68.85 | 74.99 | 15.70 | 71.36 | 69.8 | 73.1 | 13.67 |

| Height (cm) | 163.15 | 161.69 | 164.60 | 7.44 | 162.65 | 161.24 | 164.06 | 7.20 |

| Evolution (years) | 13.84 | 11.86 | 15.83 | 10.17 | 20.04 | 17.78 | 22.30 | 11.56 |

| ESR | 19.10 | 15.64 | 22.56 | 17.70 | 18.25 | 14.96 | 21.54 | 16.83 |

| CRP | 1.20 | 0.82 | 1.58 | 1.94 | 3.61 | 2.30 | 4.91 | 6.68 |

| DAS28 | 2.15 | 1.96 | 2.34 | 0.97 | 2.66 | 2.45 | 2.86 | 1.04 |

| 2018 | 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Treatment (N) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p Value | |

| Length right foot | MTX (42) | 240.48 (9.7) | 239.24 (9.8) | 0.888 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 245.09 (13.2) | 243.26 (13.6) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 243.50 (14.9) | 242.10 (15) | ||

| Other (16) | 247.56 (13.4) | 246 (14.4) | ||

| Length left foot | MTX (42) | 242.29 (10.6) | 242.48 (10.5) | 0.05 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 246.04 (13.5) | 245.06 (13) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 245.7 (15.6) | 245.75 (14.7) | ||

| Other (16) | 248.33 (14.3) | 245.67 (15.6) | ||

| Maximum height Medial Arch Right | MTX (42) | 51.94 (5.3) | 54.58 (6.9) | 0.641 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 54.34 (6.5) | 56.10 (8.3) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 54.17 (4.8) | 54.54 (7.5) | ||

| Other (16) | 50.65 (5.9) | 53.02 (7.7) | ||

| Maximum height Medial Arch Left | MTX (42) | 53.77 (5.3) | 55.50 (7.9) | 0.447 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 56.51 (6.3) | 58.35 (8.5) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 56.56 (4.7) | 56.85 (8.3) | ||

| Other (16) | 52.09 (7.2) | 56.64 (7.5) | ||

| Midfoot width Right | MTX (42) | 74.48 (5.8) | 77.01 (5.5) | 0.56 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 78.68 (6.4) | 81.77 (6.3) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 79.17 (5.8) | 82.98 (6) | ||

| Other (16) | 77.74 (5.7) | 80.38 (8.2) | ||

| Midfoot width Left | MTX (42) | 75.71 (5.3) | 76.19 (6.1) | 0.483 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 79.58 (6.7) | 79.90 (6.6) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 79.72 (5.1) | 80.98 (5.4) | ||

| Other (16) | 78.79 (5.5) | 80.33 (7.0) | ||

| Forefoot width right | MTX (42) | 89.40 (5.6) | 92.44 (5.6) | 0.345 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 92.47 (5.5) | 96.47 (6.2) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 92.15 (4.6) | 95.92 (6.3) | ||

| Other (16) | 90.84 (6.2) | 96.30 (6.9) | ||

| Forefoot width Left | MTX (42) | 89.06 (4.9) | 92.99 (5.5) | 0.958 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 92.33 (6.6) | 96.39 (6.2) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 91.16 (4.7) | 95.09 (5.8) | ||

| Other (16) | 90.01 (7) | 94.63 (8.7) | ||

| Heel width Right | MTX (42) | 64.69 (4.5) | 66.77 (6.8) | 0.867 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 67.97 (4.9) | 70.37 (5.7) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 67.12 (5.1) | 70.07 (5.9) | ||

| Other (16) | 66.74 (4.7) | 69.16 (6.8) | ||

| Heel width Left | MTX (42) | 64.64 (5.3) | 67.64 (7.1) | 0.026 |

| bDMARDs (115) | 68.20 (5) | 70.14 (5.3) | ||

| MTX+ bDMARDs (33) | 68.50 (5.1) | 71.43 (5.6) | ||

| Other (16) | 65.17 (5.1) | 70.11 (6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gamez-Guijarro, M.; Reinoso-Cobo, A.; Perez-Galan, M.J.; Ortega-Avila, A.B.; Ramos-Petersen, L.; Torrontegui-Duarte, M.; Gijon-Nogueron, G.; Lopezosa-Reca, E. Foot Anthropometry Measures in Relation to Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161656

Gamez-Guijarro M, Reinoso-Cobo A, Perez-Galan MJ, Ortega-Avila AB, Ramos-Petersen L, Torrontegui-Duarte M, Gijon-Nogueron G, Lopezosa-Reca E. Foot Anthropometry Measures in Relation to Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(16):1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161656

Chicago/Turabian StyleGamez-Guijarro, Maria, Andres Reinoso-Cobo, Maria Jose Perez-Galan, Ana Belen Ortega-Avila, Laura Ramos-Petersen, Marcelino Torrontegui-Duarte, Gabriel Gijon-Nogueron, and Eva Lopezosa-Reca. 2024. "Foot Anthropometry Measures in Relation to Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Longitudinal Study" Healthcare 12, no. 16: 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161656

APA StyleGamez-Guijarro, M., Reinoso-Cobo, A., Perez-Galan, M. J., Ortega-Avila, A. B., Ramos-Petersen, L., Torrontegui-Duarte, M., Gijon-Nogueron, G., & Lopezosa-Reca, E. (2024). Foot Anthropometry Measures in Relation to Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare, 12(16), 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12161656