Sexual Activity, Function, and Satisfaction in Reproductive-Aged Females Living with Chronic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Assessment of Sexual Activity, Function, and Satisfaction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Reporting of Sex and Gender

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

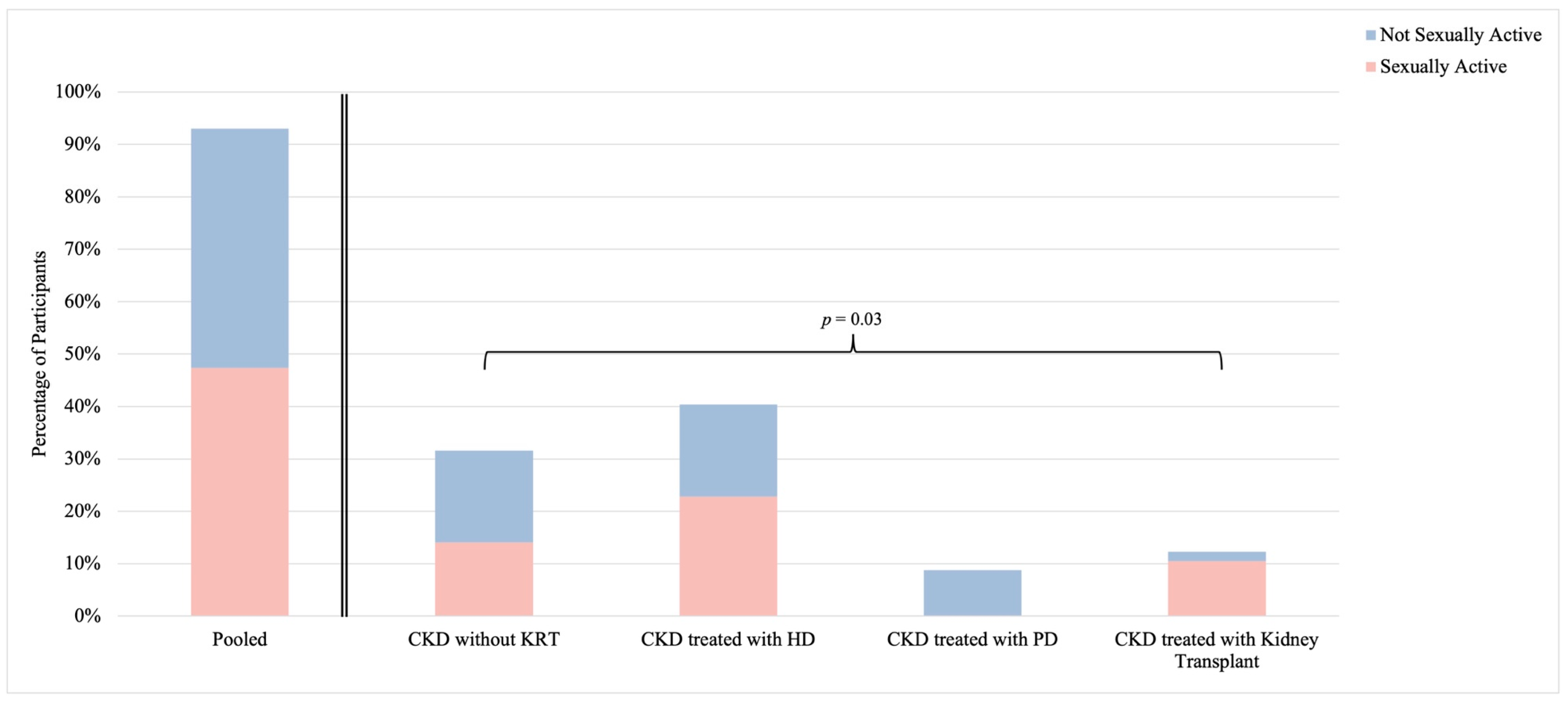

3.2. Sexual Activity

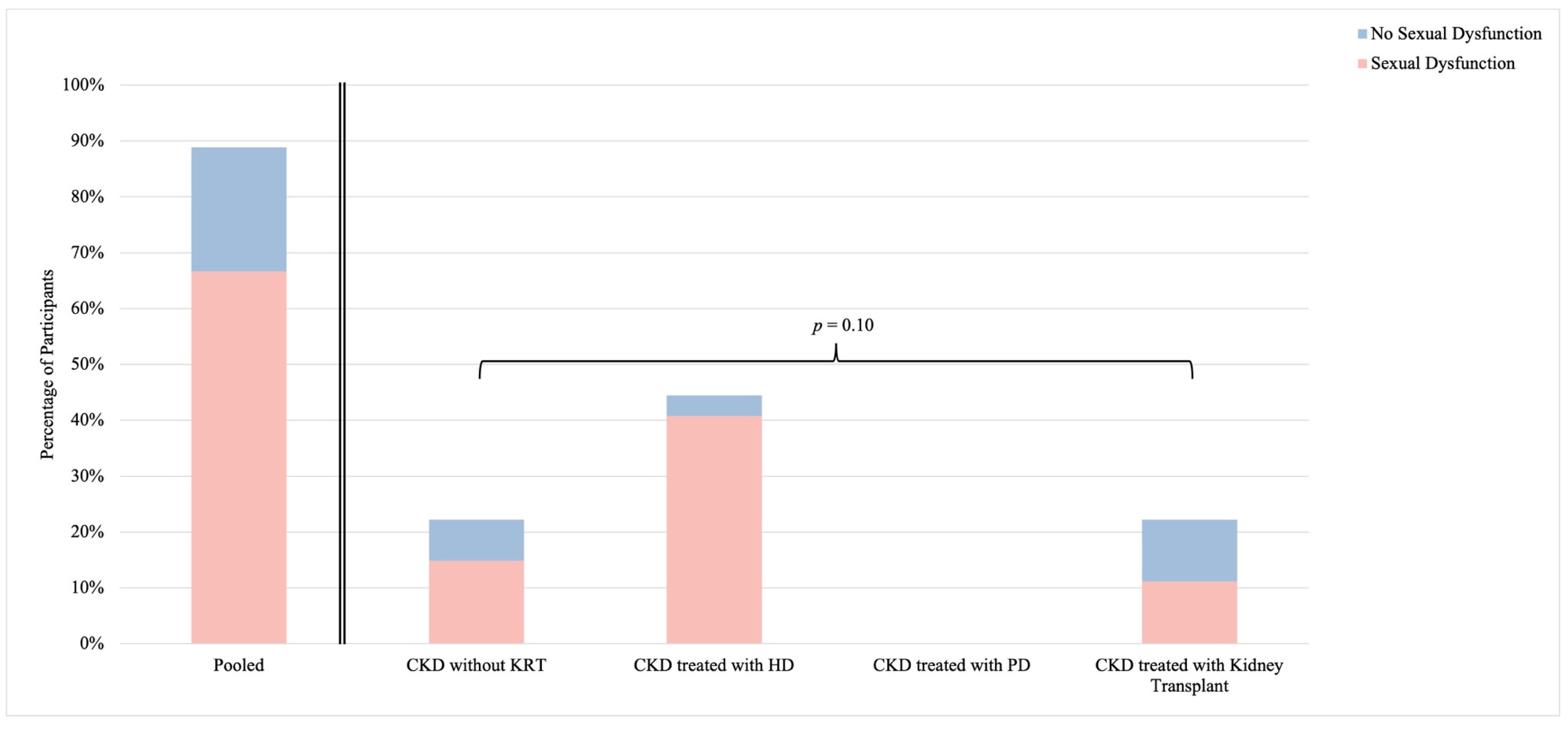

3.3. Sexual Function

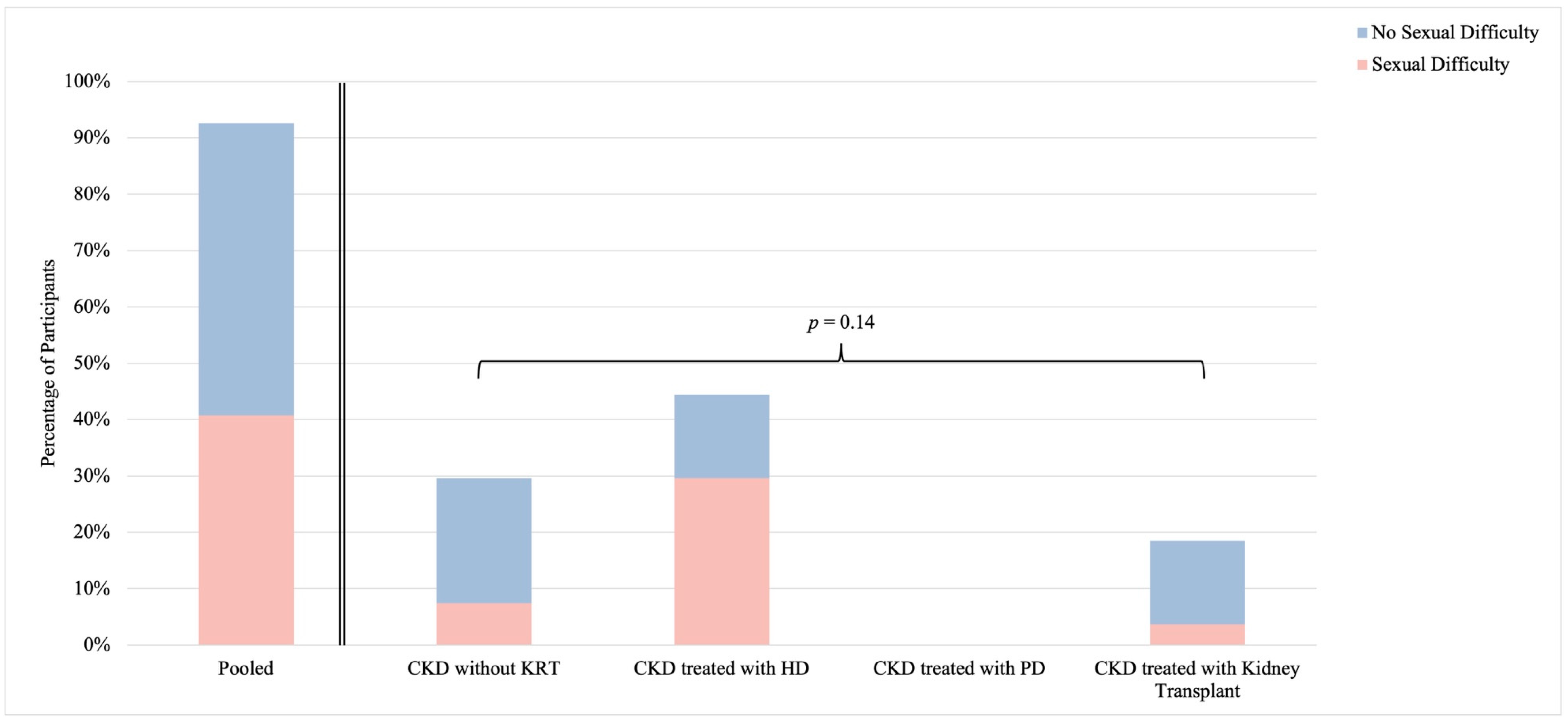

3.4. Self-Identified Sexual Difficulty

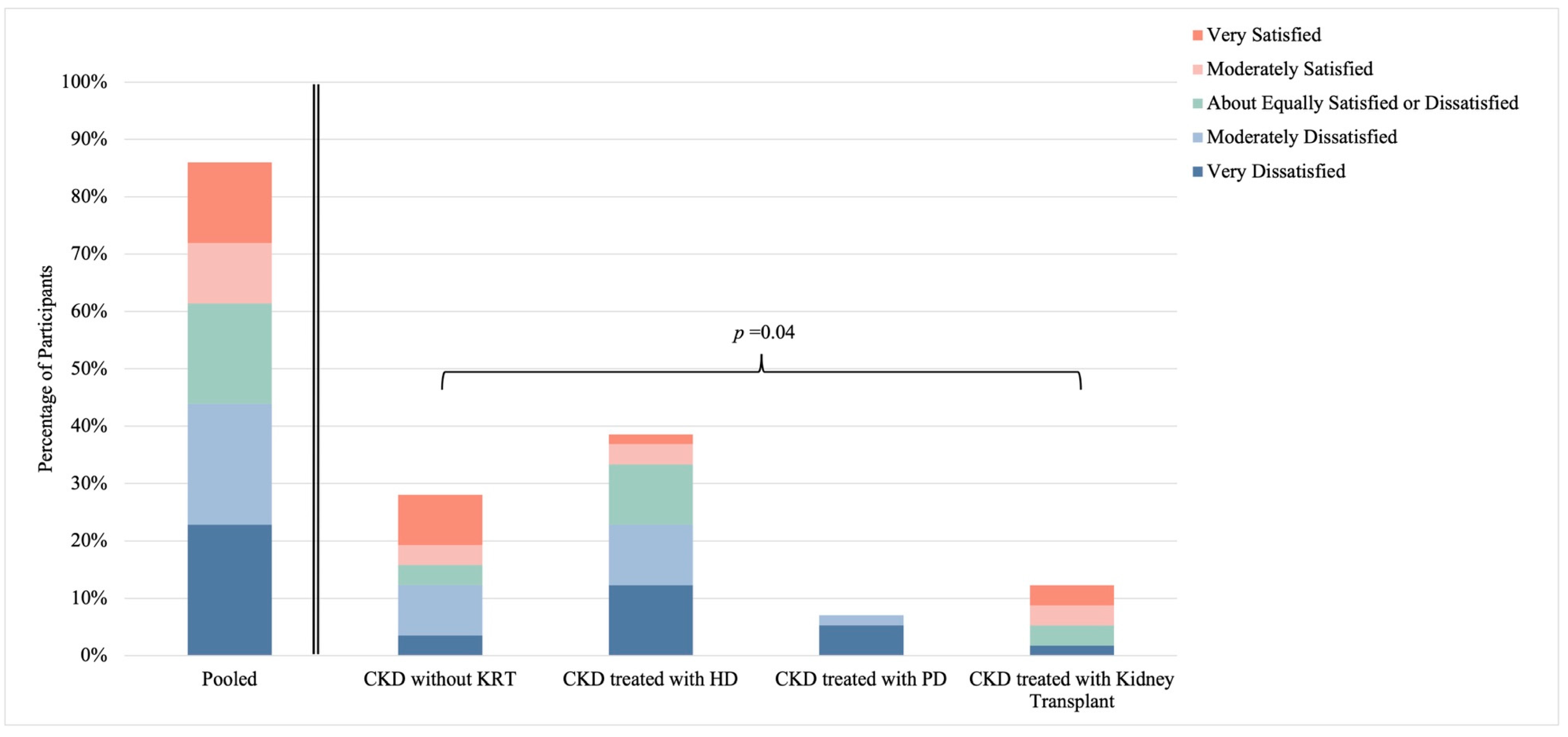

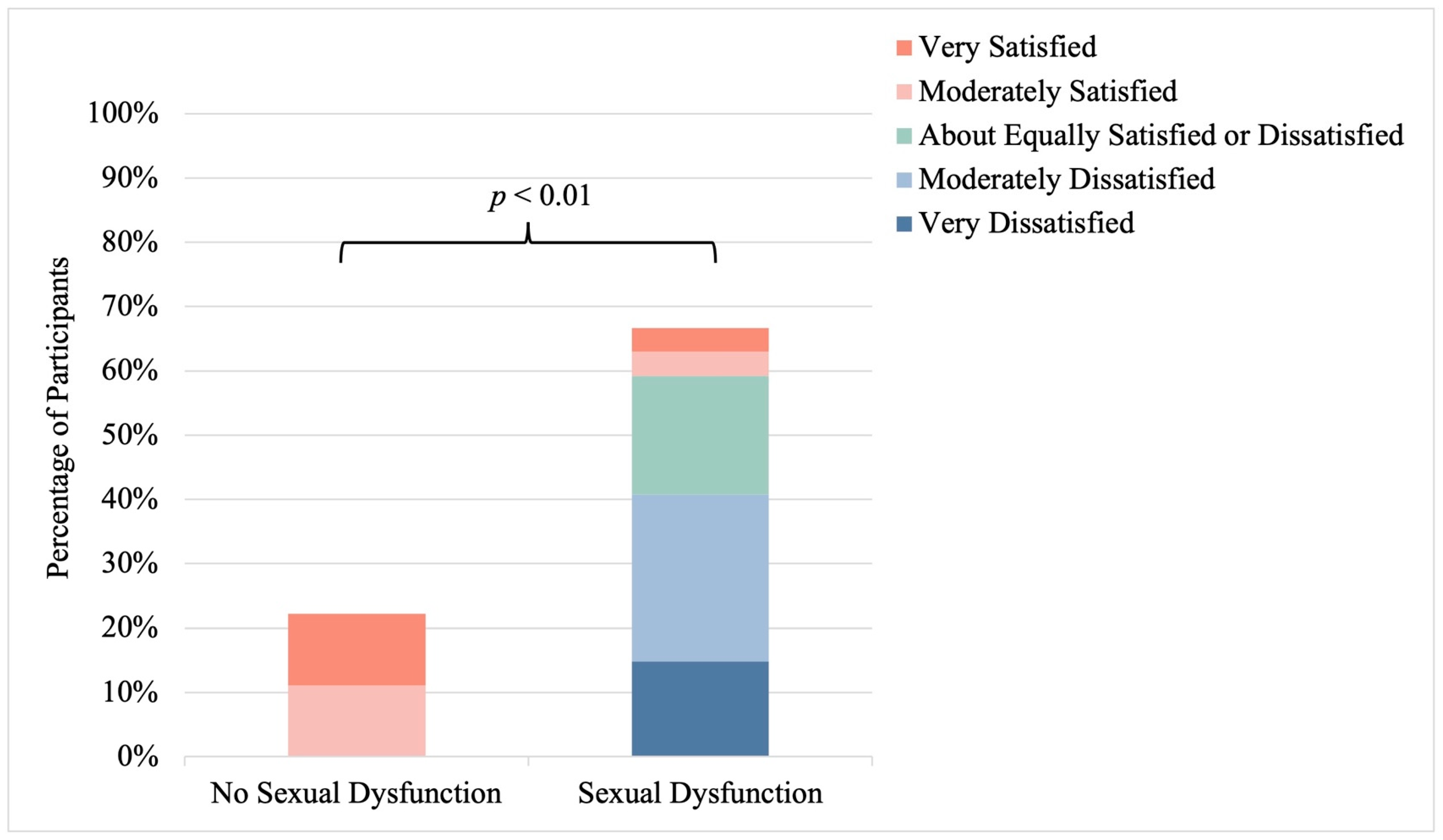

3.5. Sexual Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Bundy, J.D.; Chen, C.-S.; Kelly, T.N.; Chen, J.; He, J. A systematic analysis of worldwide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanski, S.M.; Eckersten, D.; Piccoli, G.B. Reproductive health in chronic kidney disease: The implications of sex and gender. Semin. Nephrol. 2022, 42, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Pannu, N.; Ahmed, S.B.; Elliott, M.J.; Tam-Tham, H.; Lillie, E.; Straus, S.E.; Donald, M.; Barnieh, L.; Chong, G.C.; et al. Determining the research priorities for patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyrgidis, N.; Mykoniatis, I.; Tishukov, M.; Sokolakis, I.; Nigdelis, M.P.; Sountoulides, P.; Hatzichristodoulou, G.; Hatzichristou, D. Sexual dysfunction in women with end-stage renal disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, S.D.; Vecchio, M.; Johnson, D.W.; Saglimbene, V.; Graziano, G.; Pellegrini, F. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported sexual dysfunction in CKD: A me-ta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 56, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifren, J.L. Overview of Sexual Dysfunction in Females: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Evaluation. UpToDate; May 2024. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Prescott, L.; Eidemak, I.; Harrison, A.P.; Molsted, S. Sexual dysfunction is more than twice as frequent in Danish female predialysis patients compared to age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2013, 46, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Chiu, L.H.; Chu, Y.H.; Ruan, F.F.; Liu, W.M.; Wang, P.H. Female sexual dysfunction: Definition, classification, and debates. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 52, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.; Brown, J.; Heiman, S.; Leiblum, C.; Meston, R.; Shabsigh, D.; Ferguson, R.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meston, C.M.; Freihart, B.K.; Handy, A.B.; Kilimnik, C.D.; Rosen, R.C. Scoring and interpretation of the FSFI: What can be learned from 20 years of use? J. Sex. Med. 2019, 17, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, M.K.; Sevick, M.A.; Shields, A.M.; Green, J.A.; Palevsky, P.M.; Arnold, R.M.; Weisbord, S.D. Sexual function, activity, and satisfaction among women receiving maintenance he-modialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanian, C.; McCague, H.; Tamim, H. Age at natural menopause and its associated factors in Canada: Cross-sectional analyses from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Menopause 2018, 25, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumanski, S.M.; Ahmed, S.B. Fertility and reproductive care in chronic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 2019, 32, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Fenton, K.; Johnson, A.M.; McManus, S.; Erens, B. Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2001, 77, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, S.E.; Bettencourt, R.; Barrett-Connor, E. Sexual activity and satisfaction in healthy community-dwelling older women. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.N.; Hess, R.; Thurston, R.C. Correlates of sexual activity and satisfaction in midlife and older women. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, I.B.; Eeden, S.K.V.D.; Wassel-Fyr, C.L.; Vittinghoff, E.; Brown, J.S.; Thom, D.H. Sexual activity and function in middle-aged and older women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strippoli, G.F. Collaborative Depression and Sexual Dysfunction (CDS) in Hemodialysis Working Group. Sexual dysfunction in women with ESRD requiring hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filocamo, M.T.; Zanazzi, M.; Marzi, V.L.; Lombardi, G.; Del Popolo, G.; Mancini, G.; Salvadori, M.; Nicita, G. Sexual dysfunction in women during dialysis and after renal transplantation. J. Sex. Med. 2009, 6, 3125–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, R.A.; Kershaw, V.; Radley, S. Systematic review of sexual function in older women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 267, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.G.; Skrtic, M.; Verdin, N.E.; Lanktree, M.B.; Elliott, M.J. Improving sexual function in people with chronic kidney disease: A narrative review of an unmet need in nephrology research. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2020, 7, 2054358120952202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lev-Wiesel, R.; Sasson, L.; Scharf, N.; Abu Saleh, Y.; Glikman, A.; Hazan, D.; Shacham, Y.; Barak-Doenyas, K. “Losing faith in my body”: Body image in individuals diagnosed with end-stage renal disease as reflected in drawings and narratives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M.A.; Lalonde, C.E.; Bain, J.L. Body image perceptions: Do gender differences exist? Psi Chi J. Undergrad. Res. 2012, 15, 130–138. Available online: https://web.uvic.ca/~lalonde/manuscripts/2010-Body%20Image.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H.; Arber, S. The role of the body in end-stage kidney disease in young adults: Gender, peer and intimate relationships. Chronic Illn. 2015, 11, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, R.E.; Cucinella, L.; Martella, S.; Rossi, M.; Tiranini, L.; Martini, E. Female sexual dysfunction: Prevalence and impact on quality of life. Maturitas 2016, 94, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifren, J.L.; Monz, B.U.; Russo, P.A.; Segreti, A.; Johannes, C.B. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: Prevalence and correlates. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cea Garcia, J.; Marquez Maraver, F.; Rubio Rodríguez, M.C. Cross-sectional study on the impact of age, menopause and quality of life on female sexual function. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basok, E.K.; Atsu, N.; Rifaioglu, M.M.; Kantarci, G.; Yildirim, A.; Tokuc, R. Assessment of female sexual function and quality of life in predialysis, peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, and renal transplant patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2009, 41, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytz, C.L.; Kochaksaraei, G.S.; Skeith, L.; Ronksley, P.E.; Dumanski, S.M.; Robert, M.; Ahmed, S.B. Menstrual abnormalities and reproductive lifespan in females with CKD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 1742–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, P.; Yalin, A.S.; Tiryakioglu, O.; Gazioglu, N.; Oral, G.; Sanli, O.; Onem, K.; Kadioglu, A. Sexual dysfunction in women with hyperprolactinemia: A pilot study report. J. Urol. 2005, 174, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysiak, R.; Szkróbka, W.; Okopień, B. The effect of bromocriptine treatment on sexual functioning and depressive symptoms in women with mild hyperprolactinemia. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018, 70, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszkiewicz-Rowinska, J.; Skórzewska, K.; Radowicki, S.; Sokalski, A.; Przedlacki, J.; Niemczyk, S.; Włodarczyk, D.; Puka, J.; Switalski, M. The benefits of hormone replacement therapy in pre-menopausal women with oestrogen deficiency on haemodialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1999, 14, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K.E.; Lin, L.; Bruner, D.W.; Cyranowski, J.M.; Hahn, E.A.; Jeffery, D.D.; Reese, J.B.; Reeve, B.B.; Shelby, R.A.; Weinfurt, K.P. Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to quality of life throughout the life course of U.S. adults. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, M.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Sierra, J.C. A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2014, 14, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ek, G.F.; Krouwel, E.M.; Nicolai, M.P.; Bouwsma, H.; Ringers, J.; Putter, H.; Pelger, R.C.; Elzevier, H.W. Discussing sexual dysfunction with chronic kidney disease patients: Practice patterns in the office of the nephrologist. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2350–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ek, G. Towards Adequate Care for Sexual Health and Fertility in Chronic Kidney Disease: Perspective of Patients, Partners and Care Providers. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/80204 (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Hendren, E.M.; Reynolds, M.L.; Mariani, L.H.; Zee, J.; O’shaughnessy, M.M.; Oliverio, A.L.; Moore, N.W.; Hill-Callahan, P.; Rizk, D.V.; Almanni, S.; et al. Confidence in women’s health: A cross border survey of adult nephrologists. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; James, M.T.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Wilton, S.B.; Seely, E.W.; Wheeler, D.C.; Ahmed, S.B. Sex hormone status in women with chronic kidney disease: Survey of neph-rologists’ and renal allied health care providers’ perceptions. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2017, 4, 2054358117734534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, P.; Schmidt, R.J. Sexual function in chronic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007, 14, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, O.A.; Edeki, I.R.; Oyedepo, D.S.; Falade, J.; Yisau, O.E.; Ige, O.O.; Adesida, A.O.; Palencia, H.D.; Moussa, A.S.; Abdulmalik, J.; et al. Global prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nephrol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pooled (n = 57) | CKD without KRT (n = 20) | CKD Treated with HD (n = 25) | CKD Treated with PD (n = 5) | CKD Treated with Kidney Transplant (n = 7) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38 (32, 47) a | 40 (32, 47) | 37 (32, 47) b | 35 (25, 40) | 37 (36, 41) | 0.81 |

| Self-identified Ethnicity n (%) c | 0.67 | |||||

| Black | 3 (6) | 1 (6) | 1 (4) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Caribbean | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| East Asian | 2 (4) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Filipinx | 1 (2) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Indigenous or Metis | 5 (9) | 1 (6) | 3 (13) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Latinx | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| South Asian | 4 (6) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Southeast Asian | 5 (9) | 2 (11) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| White | 32 (60) | 8 (44) | 16 (70) | 3 (60) | 5 (71) | |

| Gender Identity n (%) d | 0.49 | |||||

| Cisgender woman | 52 (96) | 19 (95) | 22 (100) | 5 (100) | 6 (86) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Cause of CKD n (%) e | 0.87 | |||||

| Acute kidney injury | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Congenital/hereditary | 6 (11) | 3 (16) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Diabetes | 11 (21) | 3 (16) | 6 (26) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 9 (17) | 3 (16) | 4 (17) | 1 (25) | 1 (14) | |

| Hypertension | 4 (8) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3 (6) | 1 (5) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Reflux nephropathy | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Unknown/other | 16 (30) | 8 (42) | 5 (22) | 1 (25) | 2 (29) | |

| Stage of CKD (among “CKD without KRT” participants only) n (%) f | N/A | |||||

| Stage 3a | 5 (28) | 5 (28) | - | - | - | |

| Stage 3b | 6 (33) | 6 (33) | - | - | - | |

| Stage 4 | 2 (11) | 2 (11) | - | - | - | |

| Stage 5 | 4 (22) | 4 (22) | - | - | - | |

| Unsure | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | - | - | - | |

| Menstruation n (%) a | <0.01 | |||||

| Current menstrual cycles | 36 (64) | 18 (90) | 10 (40) | 2 (50) | 6 (86) | |

| Secondary amenorrhea | 5 (9) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| Post-menopausal | 14 (25) | 2 (10) | 11 (44) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Unsure | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Menopausal Symptoms (among “post-menopausal” participants only) n (%) g | 0.04 | |||||

| Genitourinary | 6 (43) | 0 (0) | 6 (55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Vasomotor | 7 (50) | 0 (0) | 7 (64) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| None | 6 (43) | 2 (100) | 3 (27) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |

| Use of HRT (among “post-menopausal” participants only) n (%) h | N/A i | |||||

| Yes | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 12 (92) | 2 (100) | 9 (90) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | |

| Other Gynecologic Diagnosis n (%) e | 0.50 | |||||

| Endometriosis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Gynecologic malignancy | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Uterine fibroids | 2 (4) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| None | 47 (89) | 18 (90) | 19 (86) | 4 (100) | 6 (86) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corbett, K.S.; Chang, D.H.; Riehl-Tonn, V.J.; Ahmed, S.B.; Rao, N.; Kamar, F.; Dumanski, S.M. Sexual Activity, Function, and Satisfaction in Reproductive-Aged Females Living with Chronic Kidney Disease. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171728

Corbett KS, Chang DH, Riehl-Tonn VJ, Ahmed SB, Rao N, Kamar F, Dumanski SM. Sexual Activity, Function, and Satisfaction in Reproductive-Aged Females Living with Chronic Kidney Disease. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171728

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorbett, Kathryn S., Danica H. Chang, Victoria J. Riehl-Tonn, Sofia B. Ahmed, Neha Rao, Fareed Kamar, and Sandra M. Dumanski. 2024. "Sexual Activity, Function, and Satisfaction in Reproductive-Aged Females Living with Chronic Kidney Disease" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171728

APA StyleCorbett, K. S., Chang, D. H., Riehl-Tonn, V. J., Ahmed, S. B., Rao, N., Kamar, F., & Dumanski, S. M. (2024). Sexual Activity, Function, and Satisfaction in Reproductive-Aged Females Living with Chronic Kidney Disease. Healthcare, 12(17), 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171728