Information Support or Emotional Support? Social Support in Online Health Information Seeking among Chinese Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Older Adult OHIS

2.2. Social Support and Older Adult Health

2.3. Objectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Resource

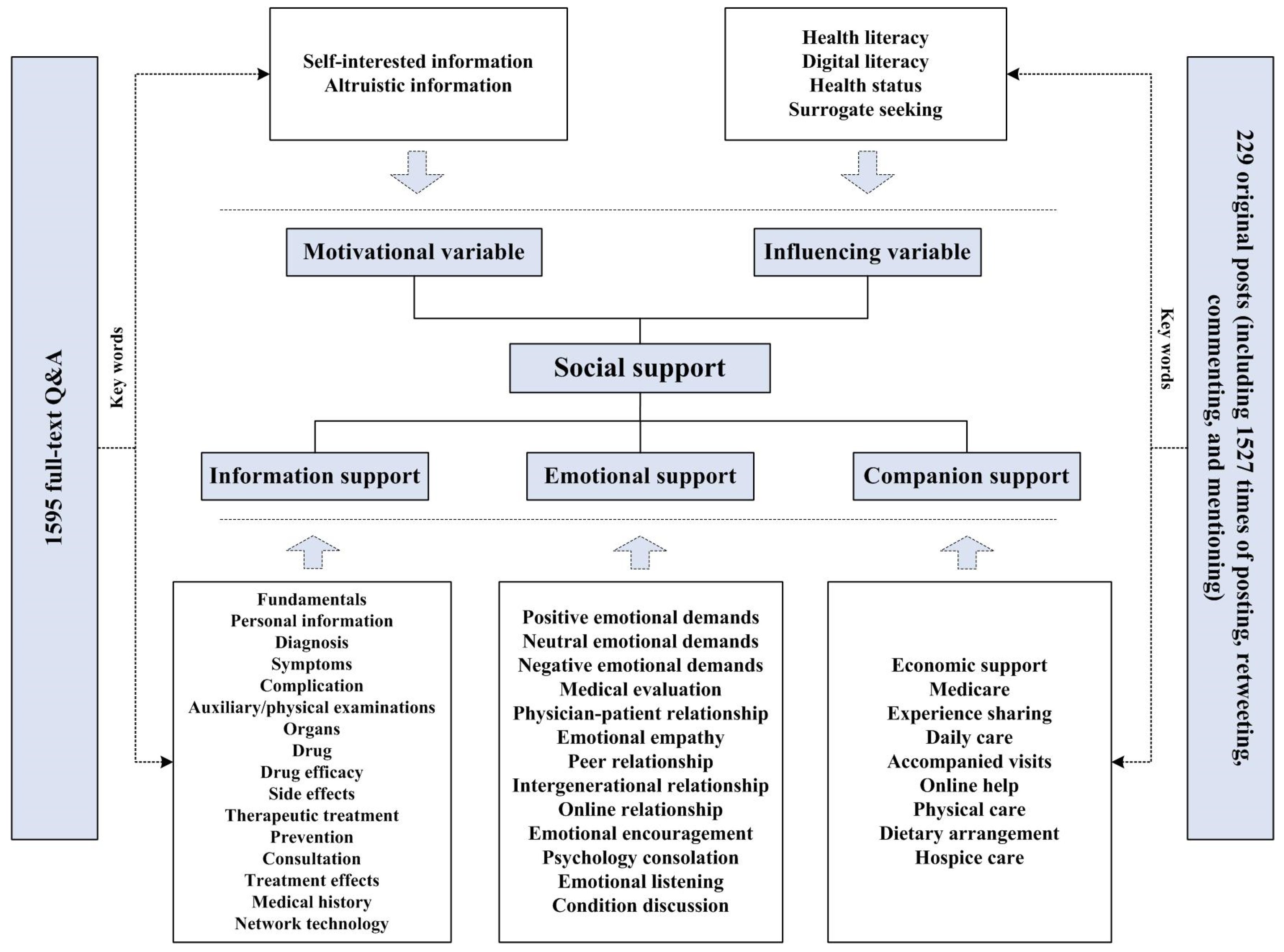

3.2. Coding Framework

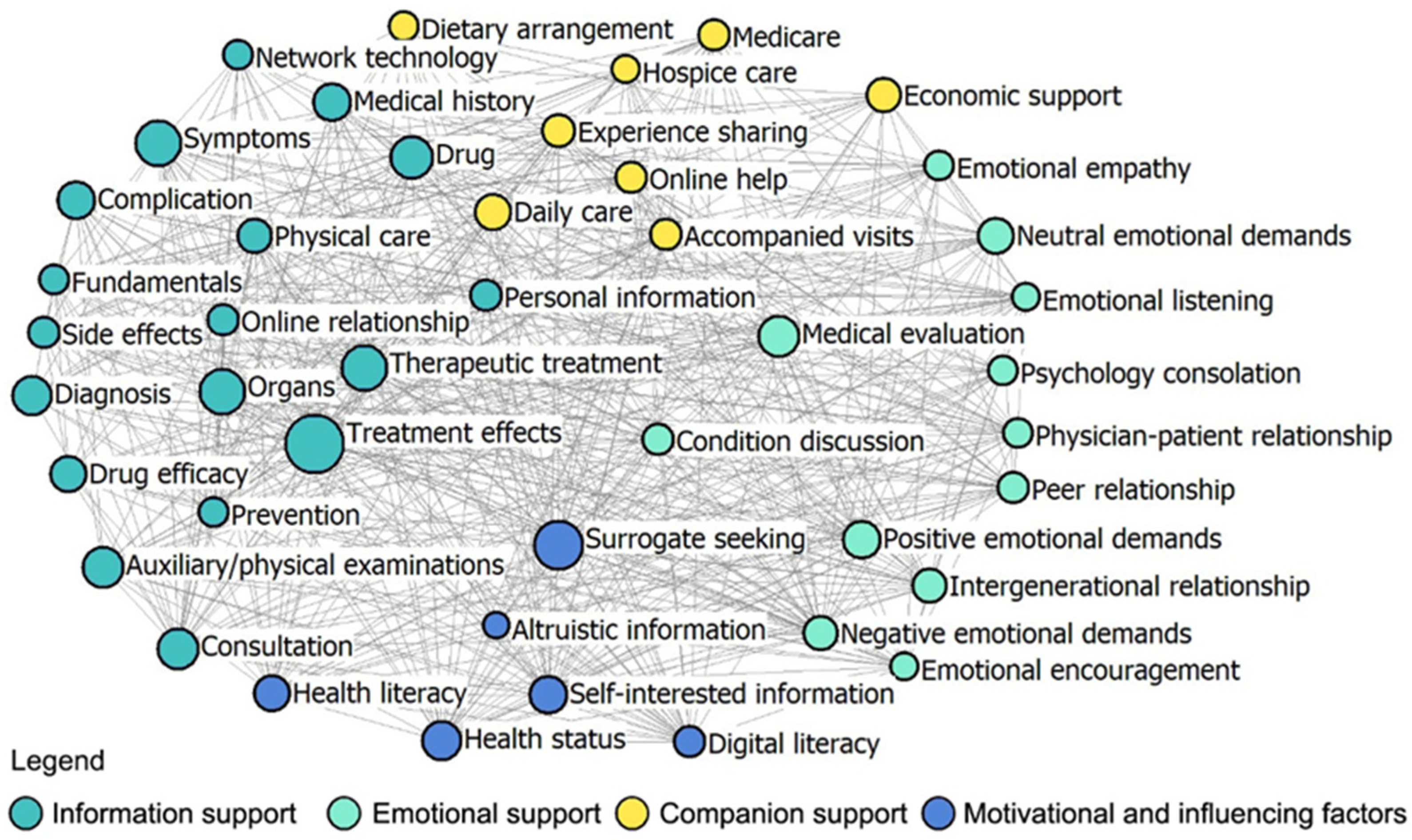

3.3. Social Network Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Similarities and Differences of Social Support in OHIS on Two Platforms

4.2. Network Nodes

4.3. Motivational and Influencing Variables for Older Adults in OHIS on Two Platforms

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Wang, X.; Liu, H. Actively coping with population aging of Chinese model. J. Popul. 2023, 45, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Magsamen-Conrad, K.; Dillon, J.M.; Billotte Verhoff, C.; Faulkner, S.L. Online health-information seeking among older populations: Family influences and the role of the medical professional. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manafo, E.; Wong, S. Exploring older adults’ health information seeking behaviors. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S. The characteristics and motivations of health answerers for sharing information, knowledge, and experiences in online environments. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrazavi, S.; Kouzekanani, K.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Bazargan-Hejazi, S.; Hashemiparast, M.; Allahverdipour, H. Correlates of older adults’ e-health information-seeking behaviors. Gerontology 2022, 68, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, S. Research on hierarchical multi-label classification of user information demand in online health community. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2023, 46, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R. Making health information accessible to patients. Aslib. Proc. 2003, 55, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wu, P. Topic Analysis of patients’ health consultation based on evidence-based decision-making theory. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2022, 45, 198–203+190. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, S.; Chauhan, S.; Gupta, P. Users’ response toward online doctor consultation platforms: SOR approach. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 1990–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, P.; Image, O.; Massagli, M.; Frost, J.; Brownstein, C.; Okun, S.; Vaughan, T.; Image, O.; Bradley, R.; Heywood, J. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ji, X. Research on emotional expression characteristics based on user portrait in online health community. Inf. Stud. Theory Appl. 2022, 45, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A.K.; Bernhardt, J.M.; Dodd, V. Older adults’ use of online and offline sources of health information and constructs of reliance and self-efficacy for medical decision making. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, B.; Stellefson, M.; Dodd, V.; Chaney, B.; Chaney, D.; Paige, S.; Alber, J. eHealth literacy and Web 2.0 health information seeking behaviors among baby boomers and older adults. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapova, L.; Klocek, A.; Elavsky, S. The role of psychological factors in older adults’ readiness to use eHealth technology: Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e14670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, B.; Nelson, D.; Kreps, G.L.; Croyle, R.; Arora, N.; Rimer, B.; Viswanath, K. Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: Findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 22, 2618–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Simpson, P.M. Health Care information seeking and seniors: Determinants of internet use. Health Mark. Q. 2015, 32, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, B.C.; Collins, N.L. A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 19, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, B.H.; Bergen, A.E. Social support concepts and measures. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Sudano, J.; Patterson, M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. J. Gerontol. B-Psychol. 2000, 55, S368–S374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.; Powell, L.; Blumenthal, J.; Norten, J.; Ironson, G.; Pitula, C.; Froelicher, E.; Czajkowski, S.; Youngblood, M.; Huber, M.; et al. A short social support measure for patients recovering from myocardial infarction: The ENRICHD social support inventory. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. 2003, 23, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsom, J.; Schulz, R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychol. Aging 1996, 11, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, H.; Shachaf, P. A structuration approach to online communities of practice: The case of Q&A communities. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 9, 1933–1944. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Dorman, S.M. Receiving social support online: Implications for health education. Health Educ. Res. 2001, 16, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerson, L.; Viswanath, K. The social context of interpersonal communication and health. J. Health Commun. 2009, 14, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.S.; Kim, K.-A.; Kim, M.; Oh, J.; Chu, S.H.; Choi, J. Measurement of digital literacy among older adults: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, D. NLPIR: A theoretical framework for applying natural language processing to information retrieval. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2003, 54, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hether, H.J.; Murphy, S.T.; Valente, T.W. A social network analysis of supportive interactions on prenatal sites. Digit. Health 2016, 2, 2055207616628700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedkin, N. The development of structure in random networks: An analysis of the effects of increasing network density on five measures of structure. Soc. Netw. 1981, 3, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.S.; Lim, J. Patient-provider communication and online health information seeking among a sample of US older adults. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilleard, C.; Higgs, P. Internet use and the digital divide in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Eur. J. Ageing 2008, 5, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hormans, G. Social behavior as exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.; Kao, K. Mother, baby and Facebook makes three: Does social media provide social support for new mothers. Media Int. Aust. 2018, 168, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz-Costa, C.; Howard, E.P.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C.; Iriarte, A.D.V.; Lachman, M.E. Peer-based strategies to support physical activity interventions for older adults: A typology, conceptual framework, and practice guidelines. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebland, S. The importance of being expert: The quest for cancer information on the Internet. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson-Lang, L.; Major, S.; Hemming, H. An exploration of search patterns and credibility issues among older adults seeking online health information. Can. J. Aging 2011, 30, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ji, X.; Guo, F. Research on the emotional expression characteristics of online health community key users in public health emergencies. J. Mod. Inform. 2021, 41, 85–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Hornik, S.; Salas, E. An empirical examination of factors contributing to the creation of successful e-learning environments. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. The information aged: A qualitative study of older adults’ use of information and communications technology. J. Aging Stud. 2004, 18, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, J.H.; Hollis-Sawyer, L. Older adults seeking healthcare information on the internet. Educ. Gerontol. 2007, 33, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; Jordan-Marsh, M. Internet use intention and adoption among Chinese older adults: From the expanded technology acceptance model perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient-to-Doctor | Patient-to-Peer | |

|---|---|---|

| Information support |  |  |

| Emotional support |  |  |

| Companion support |  |  |

| The Density Matrix | Fitness Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core–Core | Core–Periphery | Periphery–Periphery | ||

| Patient-to-Doctor | 56.955 | 13.427 | 8.468 | 0.542 |

| Patient-to-Peer | 24.57 | 4.64 | 0.000 | 0.026 |

| Degree Centrality | Closeness Centrality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | p | t | p | |

| Overall | −4.951 | <0.001 | −5.103 | <0.001 |

| Information support | −2.081 | 0.050 | −2.940 | 0.010 |

| Emotional support | −5.352 | <0.001 | −4.332 | <0.001 |

| Companion support | −2.370 | 0.045 | −3.292 | 0.011 |

| Factor | Pearson Correlation Test | Paired t-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | t | p | |

| Self-interested information | 0.377 | 0.018 | −1.835 | 0.074 |

| Altruistic information | 0.025 | 0.879 | −7.274 | <0.001 |

| Health literacy | 0.509 | <0.001 | −1.343 | 0.187 |

| Digital literacy | −0.284 | 0.080 | −2.814 | 0.008 |

| Health status | −0.173 | 0.292 | −0.548 | 0.587 |

| Surrogate seeking | 0.087 | 0.599 | 4.348 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, X.; Li, C. Information Support or Emotional Support? Social Support in Online Health Information Seeking among Chinese Older Adults. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171790

Zhu X, Li C. Information Support or Emotional Support? Social Support in Online Health Information Seeking among Chinese Older Adults. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171790

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Xiaowen, and Chang Li. 2024. "Information Support or Emotional Support? Social Support in Online Health Information Seeking among Chinese Older Adults" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171790

APA StyleZhu, X., & Li, C. (2024). Information Support or Emotional Support? Social Support in Online Health Information Seeking among Chinese Older Adults. Healthcare, 12(17), 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171790