Social Support and Adherence to Treatment Regimens among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

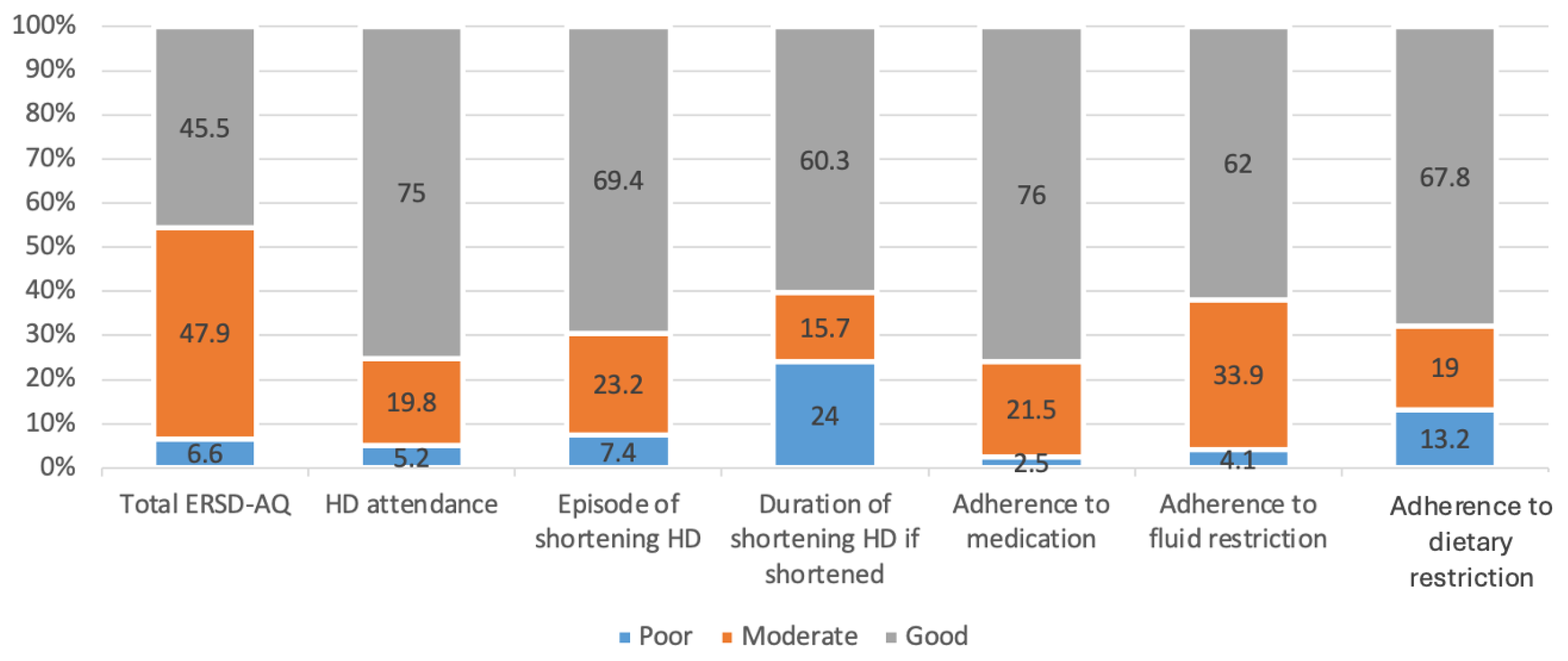

3.2. Level of Adherence to Treatment Regimens among Patients Undergoing HD

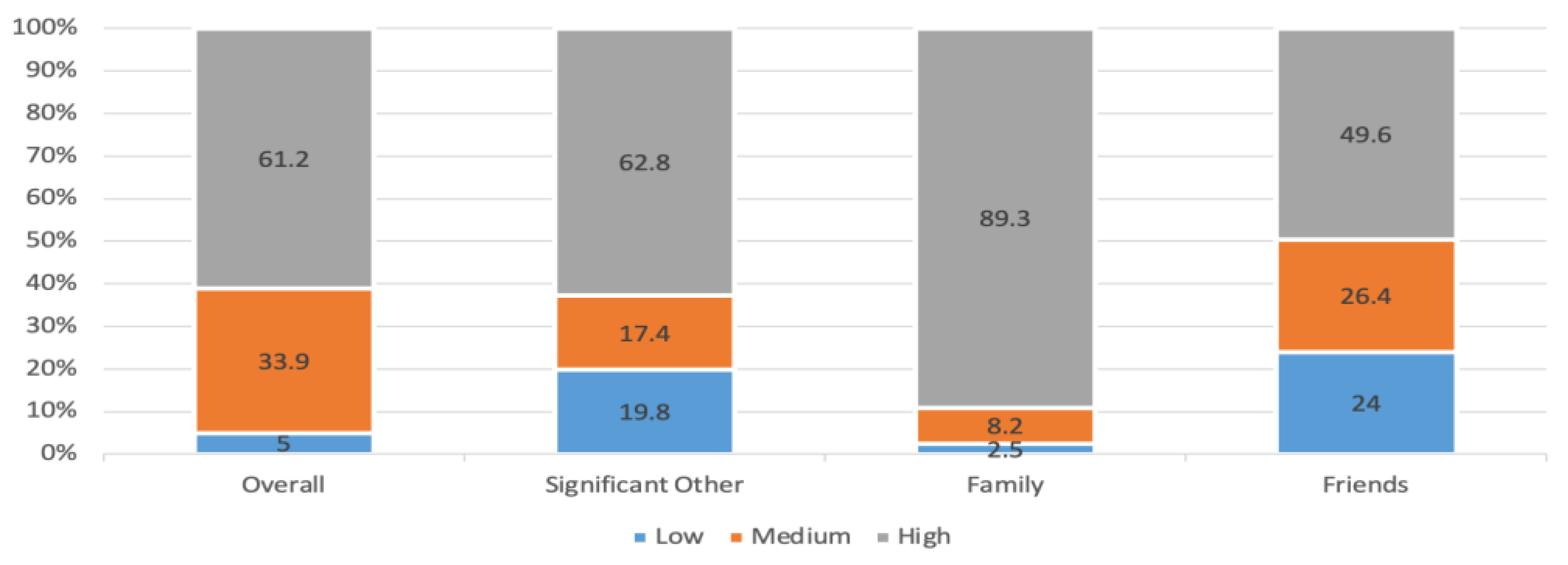

3.3. Level of Perceived Social Support among Patients Undergoing HD

3.4. Relationship between Overall Adherence to Treatment Regimens, Perceived Social Support and Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.5. Relationship between Perceived Social Support and Overall Adherence to Treatment among Patients Undergoing HD

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halle, M.P.; Nelson, M.; Kaze, F.F.; Jean Pierre, N.M.; Denis, T.; Fouda, H.; Ashuntantang, E.G. Non-adherence to hemodialysis regimens among patients on maintenance hemodialysis in sub-Saharan Africa: An example from Cameroon. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naalweh, K.S.; Barakat, M.A.; Sweileh, M.W.; Al-Jabi, S.W.; Sweileh, W.M.; Zyoud, S.H. Treatment adherence and perception in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: A cross—Sectional study from Palestine. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Hanson, C.S.; Chapman, J.R.; Halleck, F.; Budde, K.; Papachristou, C.; Craig, J.C. The preferences and perspectives of nephrologists on patients’ access to kidney transplantation: A systematic review. Transplantation 2014, 98, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Osman, M.A.; Cho, Y.; Htay, H.; Jha, V.; Wainstein, M.; Johnson, D.W. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, L.G.G.; De Seixas Rocha, M.; Junior, J.A.M.v; Paschoalin, E.L.; Paschoalin, S.R.K.P.; Sampaio Cruz, C.M. Non-adherence to haemodialysis, interdialytic weight gain and cardiovascular mortality: A cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoria, A.; Maria, T.; Vasiliki, M.; Fotoula, B.; Kalliopi, P.; Evangelos, F.; Sofia, Z. Adherence to therapeutic regimen in adults patients undergoing hemodialysis: The role of demographic and clinical characteristics. Int. Arch. Nurs. Health Care 2018, 4, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, V.R.; Kang, H.K. The worldwide prevalence of nonadherence to diet and fluid restrictions among hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2022, 32, 658–669. [Google Scholar]

- Alhawery, A.; Aljaroudi, A.; Almatar, Z.; Alqudaimi, A.A.; Al Sayyari, A.A. Nonadherence to dialysis among saudi patients—Its prevalence, causes, and consequences. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2019, 30, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, S.; Moshki, M.; Bahrami, M. The Relationship Between Social Support and Adherence of Dietary and Fluids Restrictions among Hemodialysis Patients in Iran. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 3, 11–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, N.; Wright, K.B. Social Support and Health in the Digital Age; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L.; Wu, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Gao, M.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Tian, D. Association of Social Support and Medication Adherence in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadizaker, B.; Gheibizadeh, M.; Ghanbari, S.; Araban, M. Predictors of adherence to treatment in hemodialysis patients: A structural equation modeling. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran. 2022, 36, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.; Fuertes, J.N.; Moore, M.T.; Punnakudiyil, G.J.; Calvo, L.; Rubinstein, S. Psychological and relational factors in ESRD hemodialysis treatment in an underserved community. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, H.; Ribeiro, O.; Christensen, A.J.; Figueiredo, D. Mapping patients’ perceived facilitators and barriers to In-Center Hemodialysis Attendance to the Health Belief Model: Insights from a qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 30, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, H.; Ribeiro, O.; Paúl, C.; Costa, E.; Miranda, V.; Ribeiro, F.; Figueiredo, D. Social support and treatment adherence in patients with end-stage renal disease: A systematic review. Semin. Dial. 2019, 32, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.A. Social Support: An Important Factor for Treatment Adherence and Health-related Quality of Life of Patients with End-stage Renal Disease. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2018, 44, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Evangelista, L.S.; Phillips, L.R.; Pavlish, C.; Kopple, J.D. The End-Stage Renal Disease Adherence Questionnaire (ESRD-AQ): Testing the psychometric properties in patients receiving in-center hemodialysis. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2010, 37, 377–393. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R.M.; Mohamed, H.S.; Abdel Rahman, A.A.R.; Khalifa, A.M. Relation between Therapeutic Compliance and Functional Status of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 8, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukakarangwa, M.C.; Chironda, G.; Bhengu, B.; Katende, G. Adherence to Hemodialysis and Associated Factors among End Stage Renal Disease Patients at Selected Nephrology Units in Rwanda: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 4372716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, S.; Dawood, A.E.; Ibrahim, M.; Khalil, M.; Abd, N.; Ibrahim, E.F. Effect of self-care interventions on adherence of geriatric patients undergoing hemodialysis with the therapeutic regimen. Malays. J. Nurs. 2018, 9, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Kazarian, S.S. Validation of the Arabic translation of the Multidensional Scale of Social Support (Arabic MSPSS) in a Lebanese community sample. Arab J. Psychiatr. 2012, 23, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ozen, N.; Cinar, F.I.; Askin, D.; Mut, D.; Turker, T. Nonadherence in hemodialysis patients and related factors: A multicenter study. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 27, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerbass, F.B.; Correa, D.; Santos, R.G.D.; Kruger, T.S.; Sczip, A.C.; Vieira, M.A.; Morais, J.G. Perceptions of hemodialysis patients about dietary and fluid restrictions. J. Bras. Nefrol. 2017, 39, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, G.B.; Robinson, J.R.; Walker, C.A. Adherence to Treatment by African Americans Undergoing Hemodialysis. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2018, 45, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beerappa, H.; Chandrababu, R. Adherence to dietary and fluid restrictions among patients undergoing hemodialysis: An observational study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 7, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luitel, K.; Pandey, A.; Sah, B.K.; KC, T. Therapeutic Adherence among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients under Hemodialysis in Selected Hospitals of Kathmandu Valley. J. Health Allied Sci. 2020, 10, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khattabi, G.H. Factors Affecting Non-Adherence To Treatment of Hemodialysis Patients in Makkah City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Trends Mod. Trends Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.A.; Choi, K.S.; Sim, Y.M.; Kim, S.B. Comparison of dietary compliance and dietary knowledge between older and younger Korean hemodialysis patients. J. Ren. Nutr. 2008, 18, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Castelino, R.L.; Lioufas, N.M.; Peterson, G.M.; Zaidi, S.T.R. Nonadherence to medication therapy in haemodialysis patients: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhattabi, G. Prevalence of treatment adherence among attendance at hemodialysis in Makah. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public. Health 2014, 3, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, S.M.D.S.B.; Leite, J.L.; de Godoy, S.; Tavares, J.M.A.B.; Rocha, R.G.; e Silva, F.V.C. Treatment adherence of chronic kidney disease patients on hemodialysis. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2018, 31, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohya, M.; Iwashita, Y.; Kunimoto, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Mima, T.; Negi, S.; Shigematsu, T. An Analysis of Medication Adherence and Patient Preference in Long-term Stable Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients in Japan. Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundisini, F.; Vanstone, M.; Hulan, D.; Dejean, D.; Giacomini, M. Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ differing perspectives on medication nonadherence: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitouny, S.; Cheng, L.; Wong, S.T.; Tadrous, M.; McGrail, K.; Law, M.R. Prevalence and predictors of primary nonadherence to medications prescribed in primary care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2023, 195, E1000–E1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation. Available online: https://www.scot.gov.sa/en/patients-organ-failure (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Abdel-Rasol, Z.F.M.; Abdel Aziz, T.M. Adherence to therapeutic regimens among patients undergoing hemodialysis. J. Nat. Sci. Med. 2017, 15, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkatheri, A.M.; Alyousif, S.M.; Alshabanah, N.; Abdulkareem, M. Medication adherence among adult patients on hemodialysis. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2014, 25, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, H.; Nie, A.; Chen, H.; Li, J. Predictors of medication nonadherence in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in Sichuan: A cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, K.N.; Shen, J.I.; Nishio, Y.; Haneda, M.; Dadzie, K.A.; Sheth, N.R.; Kuriyama, R.; Matsuzawa, C.; Tachibana, K.; Harbord, N.B.; et al. Patient knowledge and adherence to maintenance hemodialysis: An International comparison study. J. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2018, 22, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.M. Quality of life and social support: Perspectives of Saudi Arabian stroke survivors. Sci. Prog. 2020, 103, 0036850420947603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Number in ESRD-AQ | Adherence | Score | Poor | Moderate | Good |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | HD—attendance | 0–300 | <200 | 200–<250 | 250–300 |

| 17 | Episode of shortening HD | 0–200 | <100 | 100–<150 | 150–200 |

| 18 | Duration of shortening HD if shortened | 0–100 | <50 | 50–<75 | 75–100 |

| 26 | Adherence to medication | 0–200 | <100 | 100–<150 | 150–200 |

| 31 | Adherence to fluid restriction | 0–200 | <100 | 100–<150 | 150–200 |

| 46 | Adherence to dietary restriction | 0–200 | <100 | 100–<150 | 150–200 |

| Study Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 18–40 years | 38 (31.4%) |

| 41–50 years | 29 (24.0%) |

| 51–60 years | 23 (19.0%) |

| >60 years | 31 (25.6%) |

| Mean, SD | 48.74 ± 17.07 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 68 (56.2%) |

| Female | 53 (43.8%) |

| Educational level | |

| Not educated | 22 (18.2%) |

| Elementary school | 26 (21.5%) |

| Intermediate | 10 (08.3%) |

| High school | 46 (38.0%) |

| Bachelor or higher | 17 (14.0%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 31 (25.6%) |

| Married | 60 (49.6%) |

| Divorced or widowed | 30 (24.8%) |

| Occupational status | |

| Employed | 26 (21.5%) |

| Unemployed | 60 (49.6%) |

| Student | 08 (06.6%) |

| Retired | 27 (22.3%) |

| Monthly income (SR) | |

| <3000 SR | 67 (55.4%) |

| ≥3000 SR | 54 (44.6%) |

| Factor | Level of Adherence to Treatment Regimens | p-Value § | Level of Perceived Social Support | p-Value § | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor N (%) (n = 8) | Moderate N (%) (n = 58) | Good N (%) (n = 55) | Low N (%) (n = 6) | Medium N (%) (n = 41) | High N (%) (n = 74) | |||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 18–40 years | 04 (50.0%) | 22 (37.9%) | 12 (21.8%) | 0.026 ** | 03 (50.0%) | 14 (34.1%) | 21 (28.4%) | 0.260 |

| 41–50 years | 02 (25.0%) | 14 (24.1%) | 13 (23.6%) | 01 (16.7%) | 08 (19.5%) | 20 (27.0%) | ||

| 51–60 years | 02 (25.0%) | 13 (22.4%) | 08 (14.5%) | 01 (16.7%) | 12 (29.3%) | 10 (13.5%) | ||

| >60 years | 0 | 09 (15.5%) | 22 (40.0%) | 01 (16.7%) | 07 (17.1%) | 23 (31.1%) | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 04 (50.0%) | 30 (51.7%) | 34 (61.8%) | 0.505 | 04 (66.7%) | 19 (46.3%) | 45 (60.8%) | 0.275 |

| Female | 04 (50.0%) | 28 (48.3%) | 21 (38.2%) | 02 (33.3%) | 22 (53.7%) | 29 (39.2%) | ||

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Not educated | 01 (12.5%) | 10 (17.2%) | 11 (20.0%) | 0.335 | 01 (16.7%) | 09 (22.0%) | 12 (16.2%) | 0.754 |

| Elementary school | 01 (12.5%) | 11 (19.0%) | 14 (25.5%) | 01 (16.7%) | 10 (24.4%) | 15 (20.3%) | ||

| Intermediate | 01 (12.5%) | 08 (13.8%) | 01 (01.8%) | 01 (16.7%) | 03 (07.3%) | 06 (08.1%) | ||

| High school | 04 (50.0%) | 19 (32.8%) | 23 (41.8%) | 01 (16.7%) | 15 (36.6%) | 30 (40.5%) | ||

| Bachelor or higher | 01 (12.5%) | 10 (17.2%) | 06 (10.9%) | 02 (33.3%) | 04 (09.8%) | 11 (14.9%) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 03 (37.5%) | 17 (29.3%) | 11 (20.0%) | 0.336 | 02 (33.3%) | 11 (26.8%) | 18 (24.3%) | 0.679 |

| Married | 02 (25.0%) | 26 (44.8%) | 32 (58.2%) | 03 (50.0%) | 17 (41.5%) | 40 (54.1%) | ||

| Divorced or widowed | 03 (37.5%) | 15 (25.9%) | 12 (21.8%) | 01 (16.7%) | 13 (31.7%) | 16 (21.6%) | ||

| Occupational status | ||||||||

| Employed | 02 (25.0%) | 13 (22.4%) | 11 (20.0%) | 0.050 ** | 02 (33.3%) | 09 (22.0%) | 15 (20.3%) | 0.770 |

| Unemployed | 05 (62.5%) | 27 (46.6%) | 28 (50.9%) | 03 (50.0%) | 23 (56.1%) | 34 (45.9%) | ||

| Student | 01 (12.5%) | 07 (12.1%) | 0 | 0 | 01 (02.4%) | 07 (09.5%) | ||

| Retired | 0 | 11 (19.0%) | 16 (29.1%) | 01 (16.7%) | 08 (19.5%) | 18 (24.3%) | ||

| Monthly income (SAR) | ||||||||

| <3000 | 05 (62.5%) | 35 (60.3%) | 27 (49.1%) | 0.443 | 04 (50.0%) | 23 (56.1%) | 40 (54.1%) | 0.863 |

| ≥3000 | 03 (37.5%) | 23 (39.7%) | 28 (50.9%) | 02 (33.3%) | 18 (43.9%) | 34 (45.9%) | ||

| MSPSS | ESRD-AQ | p-Value § | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor N (%) (n = 8) | Moderate N (%) (n = 58) | Good N (%) (n = 55) | ||

| Low perceived support | 02 (25.0%) | 04 (06.9%) | 0 | 0.019 ** |

| Medium perceived support | 03 (37.5%) | 22 (37.9%) | 16 (29.1%) | |

| High perceived support | 03 (37.5%) | 32 (55.2%) | 39 (70.9%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alatawi, A.A.; Alaamri, M.; Almutary, H. Social Support and Adherence to Treatment Regimens among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191958

Alatawi AA, Alaamri M, Almutary H. Social Support and Adherence to Treatment Regimens among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Healthcare. 2024; 12(19):1958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191958

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlatawi, Amnah A., Marym Alaamri, and Hayfa Almutary. 2024. "Social Support and Adherence to Treatment Regimens among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis" Healthcare 12, no. 19: 1958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191958

APA StyleAlatawi, A. A., Alaamri, M., & Almutary, H. (2024). Social Support and Adherence to Treatment Regimens among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Healthcare, 12(19), 1958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191958