Adapting and Validating a Patient Prompt List to Assist Localized Prostate Cancer Patients with Treatment Decision Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Literature Review and Selection of Patient Prompt List Questions

2.2.2. Validation of the Patient Prompt List

2.2.3. Patient Prompt List Usefulness Evaluation

2.2.4. Questions Grouping into Thematic Domains

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

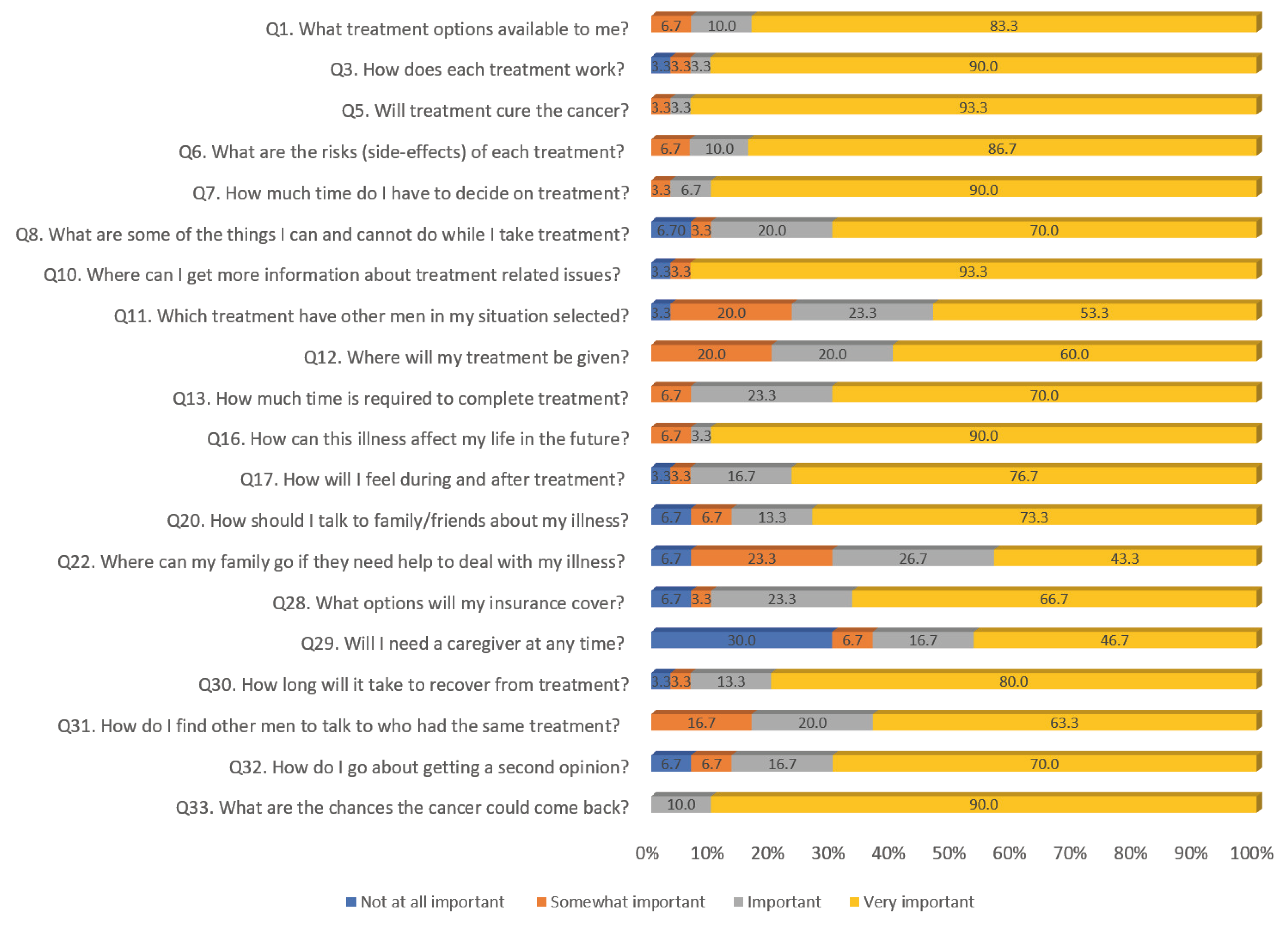

3.2. Patients’ Ratings of the Importance of Prompt List Questions

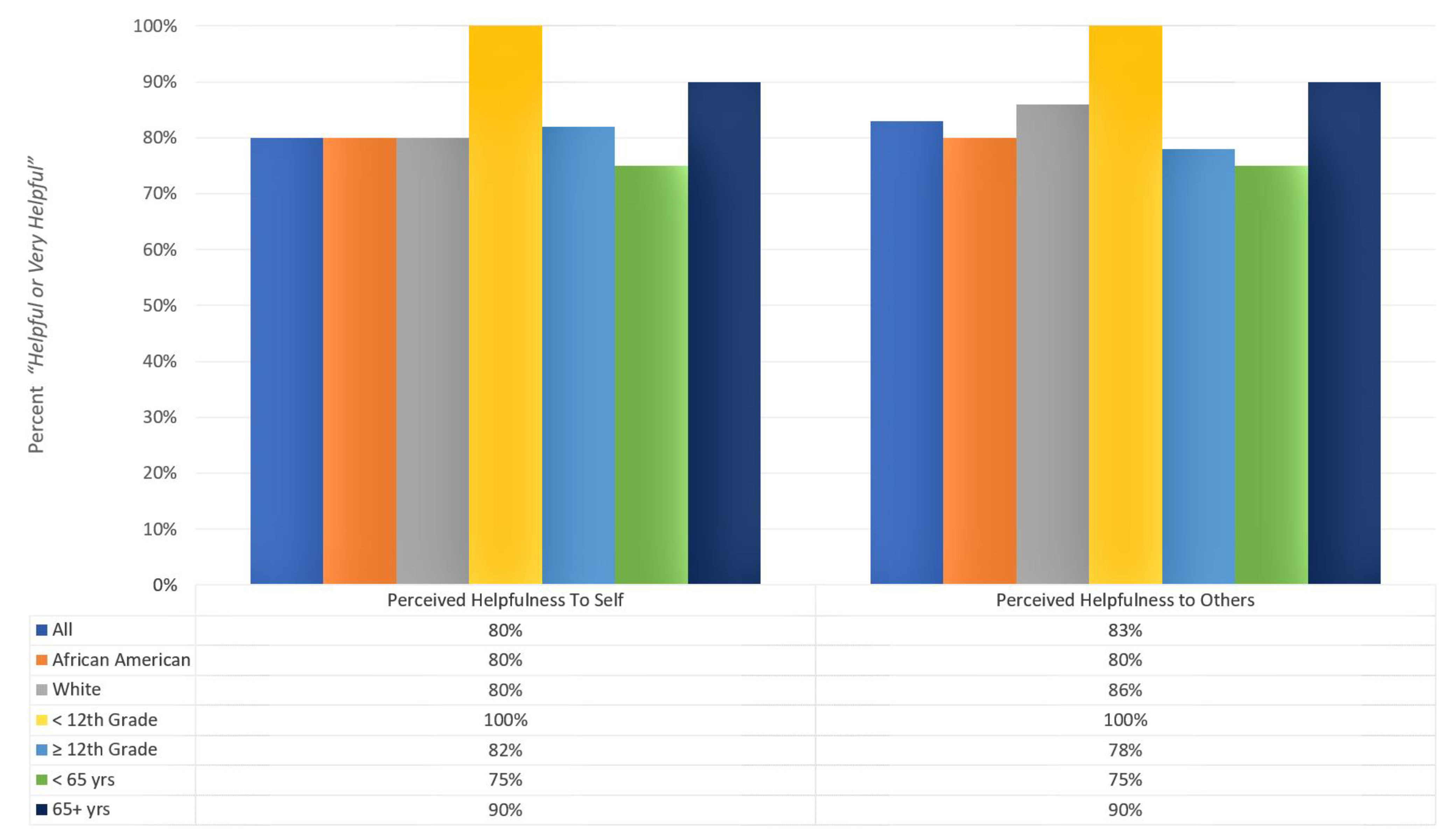

3.3. Usefulness of the Patient Prompt List to Oneself and Others

3.4. Prompt List Questions Groupings by Thematic Domains

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazer, M.W.; Bailey, D.E., Jr.; Chipman, J.; Psutka, S.P.; Hardy, J.; Hembroff, L.; Regan, M.; Dunn, R.; Crociani, C.; Sanda, M.G.; et al. Uncertainty and perception of danger among patients undergoing treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013, 111, E84–E91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, V.; McCartan, N.; Krucien, N.; Abu, V.; Ikenwilo, D.; Emberton, M.; Ahmed, H.U. Evaluating the trade-offs men with localized prostate cancer make between the risks and benefits of treatments: The COMPARE study. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, G.P., Jr.; Richardson, L.C. Visit duration for outpatient physician office visits among patients with cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 2012, 8, 2s–8s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orom, H.; Biddle, C.; Underwood, W., III; Nelson, C.J.; Homish, D.L. What is a “good” treatment decision? Decisional control, knowledge, treatment decision making, and quality of life in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 36, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.J.; Lacchetti, C.; Penson, D.F. Prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines: American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline endorsement. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, e445–e449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, M.I.; Coronado, A.C.; Schippke, J.C.; Chadder, J.; Green, E. Exploring the perspectives of patients about their care experience: Identifying what patients perceive are important qualities in cancer care. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2299–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanshawe, J.B.; Chan, V.W.S.; Asif, A.; Ng, A.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Cathcart, P.; Challacombe, B.; Brown, C.; Popert, R.; Elhage, O.; et al. Decision regret in patients with localised prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 6, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, P.N.; Dunn, S.M.; Tattersall, M.H.N.; Jones, Q.J. Patient participation in the cancer consultation: Evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Ann. Oncol. 1994, 5, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbecker, D.; Janda, M.; Yates, P. Development and piloting of a brain tumour-specific question prompt list. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.S.; Wang, C.C.; Lan, Y.H.; Tsai, H.W.; Hsiao, C.Y.; Wu, J.C.; Sheen-Chen, S.M.; Hou, W.H. Effectiveness of question prompt lists in patients with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 2984–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buizza, C.; Ghilardi, A.; Mazzardi, P.; Barbera, D.; Fremondi, V.; Bottacini, A.; Mazzi, M.A.; Goss, C. Effects of a question prompt sheet on the oncologist-patient relationship: A multi-centred randomized controlled trial in breast cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, K.; Butow, P.N.; Tattersall, M.H.; Clayton, J.M.; Davidson, P.M.; Young, J.; Walczak, A. Advanced cancer patients’ and caregivers’ use of a question prompt list. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasparian, N.A.; Mireskandari, S.; Butow, P.N.; Dieng, M.; Cust, A.E.; Meiser, B.; Barlow-Stewart, K.; Menzies, S.; Mann, G.J. “Melanoma: Questions and answers.” Development and evaluation of a psycho-educational resource for people with a history of melanoma. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4849–4859. [Google Scholar]

- Dimoska, A.; Butow, P.N.; Lynch, J.; Hovey, E.; Agar, M.; Beale, P.; Tattersall, M.H. Implementing patient question-prompt lists into routine cancer care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Turchyn, J.; Mukherjee, S.D.; Tomasone, J.R.; Fong, A.J.; Nayiga, B.K.; Ball, E.; Stouth, D.W.; Sabiston, C.M. Evaluating wall-mounted prompts to facilitate physical activity-related discussion between individuals with cancer and oncology health care providers: A pre-post survey study. Physioth. Can. 2024, 76, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouleuc, C.; Savignoni, A.; Chevrier, M.; Renault-Tessier, E.; Burnod, A.; Chvetzoff, G.; Poulain, P.; Copel, L.; Cottu, P.; Pierga, J.Y.; et al. A question prompt list for advanced cancer patients promoting advance care planning: A French randomized trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawak, S.; Chittem, M.; Dhillon, H.; Huligol, N.; Butow, P. Development of a question prompt list for Indian cancer patients receiving radiation therapy treatment and their primary family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology 2024, 33, e6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, M.; Shirai, Y.; Uchitomi, Y. Communication between cancer patients and oncologists in Japan. In New Challenges in Communication with Cancer Patients; Surbone, A., Zwitter, M.R., Stiefel, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Z.; Tung, M.; Yesantharao, P.; Zhou, A.; Blackford, A.; Smith, T.J.; Snyder, C. Feasibility and perception of a question prompt list in outpatient cancer care. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2019, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasekera, J.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Eggly, S.; Street, R.L., Jr.; Foster-Moore, T.; Isaacs, C.; Han, H.S.; Augusto, B.; Garcia, J.; Lopez, K.; et al. Question prompt list to support patient-provider communication in the use of the 21-gene recurrence test: Feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1085–e1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrborn, C.G.; Black, L.K. The economic burden of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, M.G.; Nossiter, J.; Morris, M.; Sujenthiran, A.; Skolarus, T.A.; Berry, B.; Nathan, A.; Cathcart, P.; Aggarwal, A.; van der Meulen, J.; et al. Comparison of the treatment of men with prostate cancer between the US and England: An international population-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023, 26, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, A. Global survey of clinical oncology workforce. J. Glob. Oncol. 2018, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, B.J.; Degner, L.F. Empowerment of men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1997, 20, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capirci, C.; Feldman-Stewart, D.; Mandoliti, G.; Brundage, M.; Belluco, G.; Magnani, K. Information priorities of Italian early-stage prostate cancer patients and of their health-care professionals. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 56, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, J.; Jatsch, W.; Hughes, N.; Pearce, A.; Meystre, C. Information needs and prostate cancer: The development of a systematic means of identification. BJU Int. 2004, 94, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, J.M.; Treloar, C.J.; Byles, J.E. Evaluation of a revised instrument to assess the needs of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2005, 13, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman-Stewart, D.; Brundage, M.D.; Hayter, C.; Groome, P.; Nickel, J.C.; Downes, H.; Mackillop, W.J. What prostate cancer patients should know: Variation in professionals’ opinions. Radiother. Oncol. 1998, 49, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman-Stewart, D.; Brundage, M.D.; Hayter, C.; Groome, P.; Curtis-Nickel, J.; Downes, H.; Mackillop, W.J. What questions do patients with curable prostate cancer want answered? Med. Decis. Mak. 2000, 20, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, H.R.; Coates, V.E. Adaptation of an instrument to measure the informational needs of men with prostate cancer. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 35, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlakhan, J.U.; Dhanani, S.; Berta, W.B.; Gagliardi, A.R. Optimizing the design and implementation of question prompt lists to support person-centred care: A scoping review. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 1404–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critiques and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, M.R. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Candidate Prompt List Questions | S-CVI (Scale) | Item-Level Agreement | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. What treatment options are available to me? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q2. Which treatment does he/she recommend for me? | 0.75 | 0.67 | Delete |

| Q3. How does each treatment option work? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q4. What are my chances of dying from this illness with each treatment? | 0.75 | 0.33 | Delete—Covered under Q6 or Q16 |

| Q5. Will treatment cure the cancer? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q6. What are the risks (side effects) of each treatment? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q7. How much time do I have to decide on treatment? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q8. What are some of the things I can and cannot do while I take treatment? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q9. What caused my problem? | 0.75 | 0.50 | Delete |

| Q10. Where can I get more information about treatment-related issues? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q11. Which treatment have other men in my situation selected? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q12. Where will my treatment be given? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q13. How much time is required to complete each treatment? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q14. What are the chances my illness might spread with no treatment right away? | 0.75 | 0.50 | Delete—Covered under Q5 |

| Q15. What treatment can I receive later if my first treatment choice is unsuccessful? | 0.75 | 0.50 | Delete—Covered under Q3 |

| Q16. How can this illness affect my life in the future? | 0.75 | 0.83 | Retain |

| Q17. How will I feel during and after treatment? | 0.75 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q18. Who should I call if I have any concerns during treatment? | 0.75 | 0.33 | Delete—Covered under Q12 |

| Q19. What side effects should I report to the doctor/nurse? | 0.75 | 0.67 | Delete—Covered under Q6 |

| Q20. How should I talk to family and friends about my illness? | 0.75 | 0.83 | Retain |

| Q21. Can I continue with my usual activities (e.g., hobbies)? | 0.75 | 0.67 | Delete—Covered under Q8 |

| Q22. Where can my family go if they need help to deal with my illness? | 0.75 | 0.83 | Retain |

| Q23. Who do I talk to about alternative treatments? | 0.75 | 0.50 | Delete—Covered under Q10 |

| Q24. What do the results of blood tests mean? | 0.75 | 0.67 | Delete—Covered under Q5 |

| Q25. Will there be changes in the usual things I can do with and for my family? | 0.75 | 0.67 | Delete—Covered under Q8 |

| Q26. Are there groups available to talk to other people who had prostate cancer? | 0.75 | 0.50 | Delete—Will cover under recommended addition |

| Q27. Are there ways to prevent/ease treatment side effects? | 0.75 | 0.67 | Delete—Covered under Q6 |

| Candidate Prompt List Questions | S-CVI (Scale) | Item-Level Agreement | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. What treatment options are available to me? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q3. How does each treatment option work? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q5. Will treatment cure the cancer? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q6. What are the risks (side effects) of each treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q7. How much time do I have to decide on treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q8. What are some of the things I can and cannot do while I take treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q10. Where can I get more information about treatment-related issues? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q11. Which treatment have other men in my situation selected? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q12. Where will my treatment be given? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q13. How much time is required to complete each treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q16. How can this illness affect my life in the future? | 0.96 | 0.83 | Retain |

| Q17. How will I feel during and after treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q20. How should I talk to family and friends about my illness? | 0.96 | 0.83 | Retain |

| Q22. Where can my family go if they need help to deal with my illness? | 0.96 | 0.83 | Retain |

| Q28. What options will my insurance cover? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q29. Will I need a caregiver at any time? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q30. How long will it take to recover from treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q31. How do I find other men to talk to who had the same treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q32. How do I go about getting a second opinion? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

| Q33. What are the chances the cancer could come back after treatment? | 0.96 | 1.00 | Retain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ross, L.; Collins, L.; Uzoaru, F.; Preston, M.A. Adapting and Validating a Patient Prompt List to Assist Localized Prostate Cancer Patients with Treatment Decision Making. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191981

Ross L, Collins L, Uzoaru F, Preston MA. Adapting and Validating a Patient Prompt List to Assist Localized Prostate Cancer Patients with Treatment Decision Making. Healthcare. 2024; 12(19):1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191981

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoss, Levi, Linda Collins, Florida Uzoaru, and Michael A. Preston. 2024. "Adapting and Validating a Patient Prompt List to Assist Localized Prostate Cancer Patients with Treatment Decision Making" Healthcare 12, no. 19: 1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191981

APA StyleRoss, L., Collins, L., Uzoaru, F., & Preston, M. A. (2024). Adapting and Validating a Patient Prompt List to Assist Localized Prostate Cancer Patients with Treatment Decision Making. Healthcare, 12(19), 1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191981