An Exploration of Pediatricians’ Professional Identities: A Q-Methodology Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

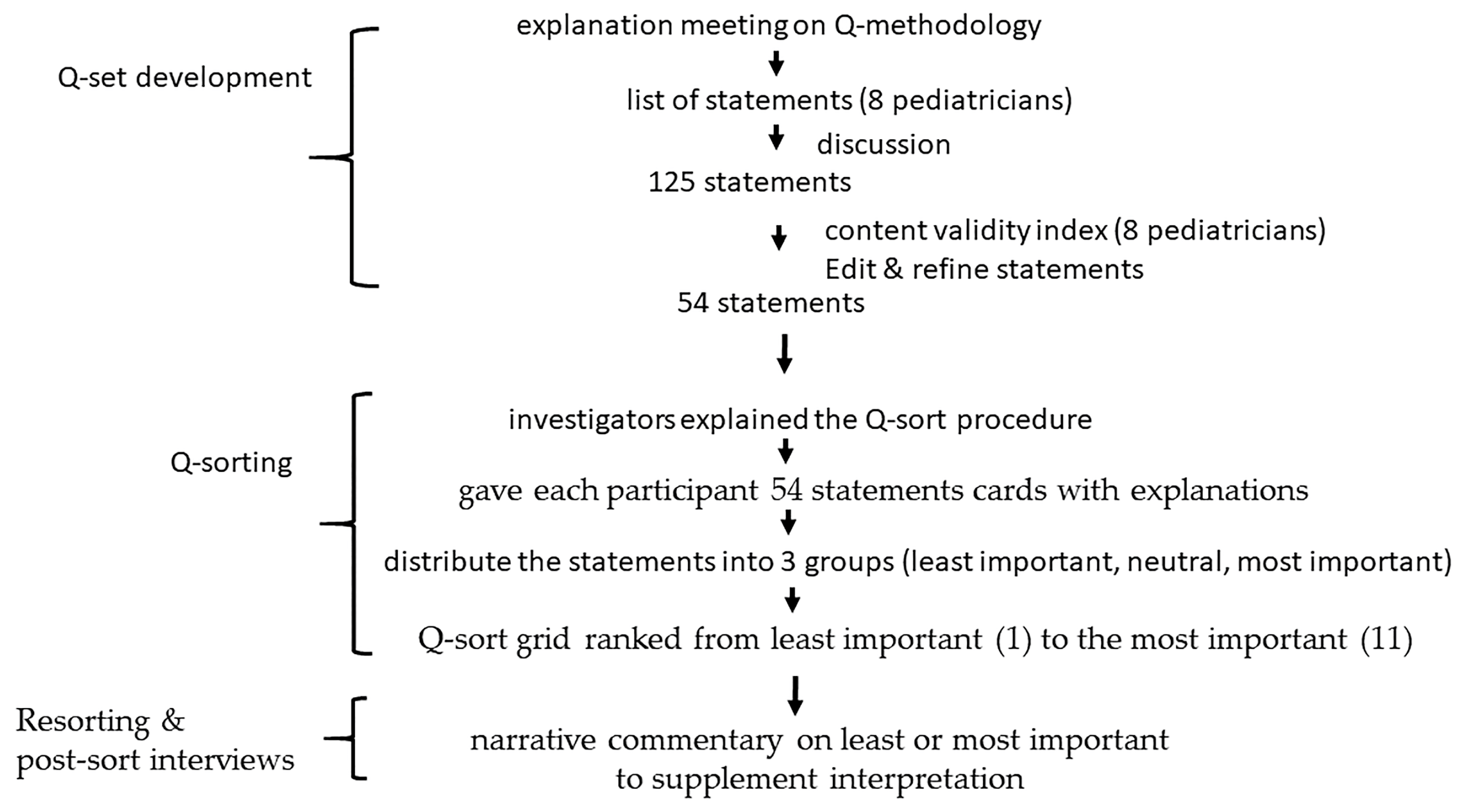

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Procedure and Collection

2.3.1. Validity

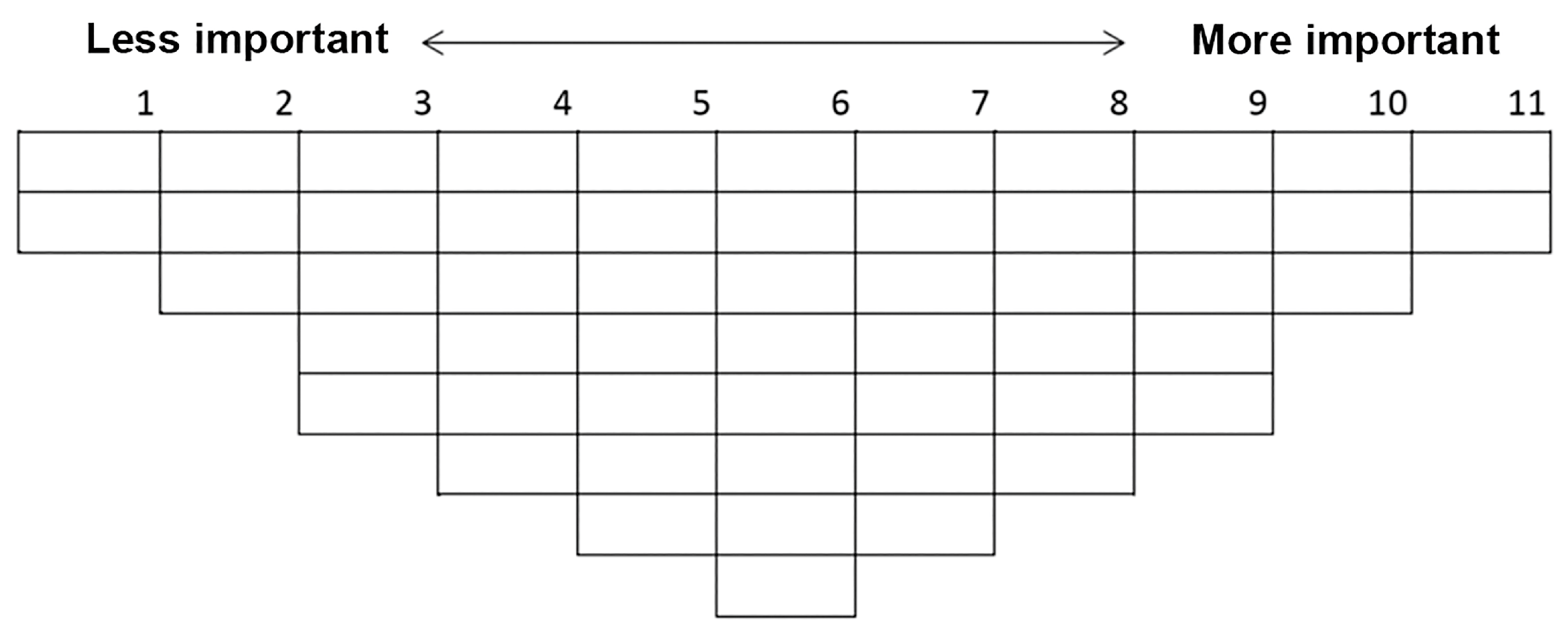

2.3.2. Q-Sorting

2.3.3. Resorting and Post-Sort Interviews

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Interpretation of Factors

3. Results

3.1. Viewpoint 1: Professional Recognition

3.2. Viewpoint 2: Patient Communication

3.3. Viewpoint 3: Empathy

3.4. Viewpoint 4: Insight

3.5. Consensus Statements

4. Discussion

4.1. Research as the Least Important

4.2. Study Implications

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnhoorn, P.C.; Houtlosser, M.; Ottenhoff-de Jonge, M.W.; Essers, G.; Numans, M.E.; Kramer, A.W.M. A practical framework for remediating unprofessional behavior and for developing professionalism competencies and a professional identity. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstein, A.H. Physician disruptive behaviors: Five year progress report. World J. Clin. Cases 2015, 3, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.M.; Hong, A.J. “Not yet a doctor”: Medical student learning experiences and development of professional identity. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.J.; Byington, C.L.; Olson, L.M.; Ramirez, K.P.G.; Zeng, S.; Lopez, A.M. A Conceptual Model for Understanding Academic Physicians’ Performances of Identity: Findings From the University of Utah. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahabi, M.; Mohammadi, N.; Koohpayehzadeh, J.; Soltani Arabshahi, S.K. The attainment of physician’s professional identity through meaningful practice: A qualitative study. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2020, 34, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.M.; Thammasitboon, S.; Ward, M.A.; Kline, M.W.; Raphael, J.L.; Turner, T.L.; Orange, J.S. Implementation of a Novel Curriculum and Fostering Professional Identity Formation of Pediatrician-Scientists. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 5–7.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, R.; Cross, V.; Moore, A. The construction of professional identity by physiotherapists: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, A.; Kamran, R.; Haroon, F.; Bano, I. Burnout among pediatric residents and junior consultants working at a tertiary care hospital. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, T.E.; Feraco, A.M.; Tuysuzoglu Sagalowsky, S.; Williams, D.; Litman, H.J.; Vinci, R.J. Pediatric Resident Burnout and Attitudes Toward Patients. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Junior, D. The formation of citizens: The pediatrician’s role. J. Pediatr. 2016, 92, S23–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuilanoff, E. Burnout and Our Professional Identity Crisis as Clinical Educators. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 616–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triemstra, J.D.; Iyer, M.S.; Hurtubise, L.; Poeppelman, R.S.; Turner, T.L.; Dewey, C.; Karani, R.; Fromme, H.B. Influences on and Characteristics of the Professional Identity Formation of Clinician Educators: A Qualitative Analysis. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, T.R.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Crandall, S.; Wooten, R.; Gillette, C. A comparison of professional identity experiences among minoritized medical professionals. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2022, 114, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurth, S.; Sader, J.; Cerutti, B.; Broers, B.; Bajwa, N.M.; Carballo, S.; Escher, M.; Galetto-Lacour, A.; Grosgurin, O.; Lavallard, V.; et al. Medical students’ perceptions and coping strategies during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: Studies, clinical implication, and professional identity. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevino, R.; Poitevien, P. Professional identity formation for underrepresented in medicine learners. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2021, 51, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldie, J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, e641–e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternszus, R.; Slattery, N.K.; Cruess, R.L.; Cate, O.T.; Hamstra, S.J.; Steinert, Y. Contradictions and Opportunities: Reconciling Professional Identity Formation and Competency-Based Medical Education. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2023, 12, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, D.; Gough, J. Perceptions of professional identity: A story from paediatrics. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2004, 26, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandford, E.; Wang, T.; Nguyen, C.; Rassbach, C.E. Sense of Belonging and Professional Identity Among Combined Pediatrics-Anesthesiology Residents. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 22, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R. Bibliography on Q technique and its methodology. Percept. Mot. Skills 1968, 26, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; Kim, G.M. Patterns of anger expression among middle-aged Korean women: Q methodology. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2012, 42, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, J.C.; Willoughby, P.; Rosenberg, C.A.; Mrtek, R.G. Statistical methodology: VII. Q-methodology, a structural analytic approach to medical subjectivity. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1998, 5, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Xiao, X.; Nkambule, N.; Ngerng, R.Y.L.; Bullock, A.; Monrouxe, L.V. Exploring emergency physicians’ professional identities: A Q-method study. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2021, 26, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meade, L.B.; Caverzagie, K.J.; Swing, S.R.; Jones, R.R.; O’Malley, C.W.; Yamazaki, K.; Zaas, A.K. Playing with curricular milestones in the educational sandbox: Q-sort results from an internal medicine educational collaborative. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, S.Y.; Babovic, M.; Liu, G.R.; Gugel, A.; Monrouxe, L.V. Differing viewpoints around healthcare professions’ education research priorities: A Q-methodology approach. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2021, 26, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, J.B.; Morin, K.H. Q-Sample Construction: A Critical Step for a Q-Methodological Study. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramlo, S. Centroid and theoretical rotation: Justification for their use in Q methodology research. Mid-West. Educ. Res. 2016, 28, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, S.; Stenner, P. Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2005, 2, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehner, T.M. Elevating the Profession through Education, Community, and Professional Recognition. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2020, 48, 7A. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.E. A professional recognition system using peer review. J. Nurs. Adm. 1987, 17, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renger, D.; Miche, M.; Casini, A. Professional Recognition at Work: The Protective Role of Esteem, Respect, and Care for Burnout Among Employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, K.; Shumsky, C.J. Pediatric procedures. The explanation should always come first. Nursing 1975, 5, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannoni, C. Communication between nurse and hospitalized child. Soins Pediatr. Pueric. 2000, 194, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Corlett, J.; Twycross, A. Negotiation of parental roles within family-centred care: A review of the research. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, N.E. Discussing difficult issues with patients and parents. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2006, 23, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousignant, B.; Eugene, F.; Jackson, P.L. A developmental perspective on the neural bases of human empathy. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2017, 48, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, J.Y.; Arman, M.; Castren, M.; Forsner, M. Meaning of caring in pediatric intensive care unit from the perspective of parents: A qualitative study. J. Child Health Care 2014, 18, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreault, J.; Carnevale, F.A. Should I stay or should I go? Parental struggles when witnessing resuscitative measures on another child in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 13, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.; Percy, M.; Hughes, J. Nursing therapeutics: Teaching student nurses care, compassion and empathy. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e1–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, A.A.; Spijkerman, J.; Muskiet, F.D.; Sauer, P.J. Physician end-of-life decision-making in newborns in a less developed health care setting: Insight in considerations and implementation. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgren, N.; Lindecrantz, K.; Thordstein, M.; Hedstrom, A.; Wallin, B.G.; Andreasson, S.; Flisberg, A.; Kjellmer, I. Remote sessions and frequency analysis for improved insight into cerebral function during pediatric and neonatal intensive care. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2003, 7, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristori, M.V.; Mortera, S.L.; Marzano, V.; Guerrera, S.; Vernocchi, P.; Ianiro, G.; Gardini, S.; Torre, G.; Valeri, G.; Vicari, S.; et al. Proteomics and Metabolomics Approaches towards a Functional Insight onto AUTISM Spectrum Disorders: Phenotype Stratification and Biomarker Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehari, K.R.; Moore, W.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Varney, O.; Berg, K.; Leff, S.S. Cyberbullying prevention: Insight and recommendations from youths, parents, and paediatricians. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullrich, N.; Botelho, C.A.; Hibberd, P.; Bernstein, H.H. Research during pediatric residency: Predictors and resident-determined influences. Acad. Med. 2003, 78, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeton, K.; Fenner, D.E.; Johnson, T.R.; Hayward, R.A. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Varkey, P.; Boone, S.L.; Satele, D.V.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Viewpoints (N) | Eigenvalue | Explained Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Professional recognition (9) | 8.4 | 21.1 |

| 2. Patient communication (9) | 8.1 | 20.3 |

| 3. Empathy (6) | 5.9 | 14.8 |

| 4. Insight (4) | 3.8 | 9.4 |

| Total | Professional Recognition | Patient Communication | Empathy | Insight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. responder | 28 (100%) | 9 (32%) | 9 (32%) | 6 (22%) | 4 (14%) |

| Age | |||||

| Range | 27–62 | 28–36 | 27–57 | 38–62 | 34–52 |

| Average | 39.9 | 31.4 | 40.8 | 48.2 | 44.8 |

| Years in Pediatrics (Average) | 12.74 | 5.78 | 13.4 | 20.5 | 15.25 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 11 (39.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| Female | 17 (60.7%) | 5 (55.6%) | 7 (77.8%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 8 (28.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 5 (55.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Married | 20 (71.4%) | 6 (66.7%) | 4 (44.5%) | 6 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| Non-clinical work | |||||

| Teaching | 19 (67.9%) | 6 (66.7%) | 6 (66.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 3 (75%) |

| Research | 26 (92.9%) | 9 (100%) | 8 (88.9%) | 6 (100%) | 3 (75%) |

| Rank | |||||

| Attending | 16 (57.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 5 (55.6%) | 6 (100%) | 3 (75%) |

| Resident | 12 (42.9%) | 7 (77.8%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

| Professional Recognition | Patient Communication | Empathy | Insight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Professional recognition | 1 | |||

| 2. Patient communication | 0.61 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. Empathy | 0.38 *** | 0.58 *** | 1 | |

| 4. Insight | 0.41 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.60 *** | 1 |

| Viewpoints | Statements | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Professional recognition | (1) Keen observation as a professional | 11 |

| (20) At the right time to give family a peace of mind | 10 | |

| (22) Discuss with family as a work partner | 9 | |

| (6) Pediatric patient-centered care | 8 | |

| (10) Things that kids care about | 6 | |

| (33) Can know what emotional response or wording is | 3 | |

| (38) Be patient with family members and sick children | 3 | |

| (49) Learned knowledge and spiritual satisfaction from sisters | 2 | |

| (51) Centered on lifestyle and well-being | 2 | |

| (48) Communication skills with the family | 1 | |

| 2. Patient communication | (16) The ability to soothe children | 11 |

| (22) Discuss with family as a work partner | 9 | |

| (49) Learned knowledge and spiritual satisfaction from sisters | 8 | |

| (38) Be patient with family members and sick children | 6 | |

| (10) Things that children care about | 6 | |

| (31) Communicate with colleagues for patients | 5 | |

| (51) Centered on lifestyle and well-being | 5 | |

| (41) Extensive with general knowledge | 3 | |

| 3. Empathy | (34) Resilience | 9 |

| (23) Safety climate for patient care | 8 | |

| (48) Communication skills with the family | 5 | |

| (16) The ability to soothe children | 5 | |

| (22) Discuss with family as a work partner | 5 | |

| (6) Pediatric patient-centered care | 3 | |

| 4. Insight | (16) The ability to soothe children | 11 |

| (1) Keen observation as a professional | 9 | |

| (33) Can know what emotional response or wording is | 8 | |

| (6) Pediatric patient-centered care | 8 | |

| (23) Safety climate for patient care | 8 | |

| (38) Be patient with family members and sick children | 6 | |

| (51) Centered on lifestyle and well-being | 5 | |

| (48) Communication skills with the family | 5 | |

| (10) Things that kids care about | 4 |

| Viewpoints | High Priority | Low Priority |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Professional recognition | F-R-29: [Medical knowledge] Since I am a pediatrician, I feel that even though I put that affinity, comforting ability, observation ability and other things to the back, I don’t think I can diagnose the disease. Hmm! Yes! So, I always felt more knowledgeable with things before, that is, at least the training process may be quite important to me, right. (resident physician) | F-A-42C: Unexpected assigned teaching; it is something that you will have as a doctor. It has nothing to do with the pediatrician, right. (resident physician) |

| F-R-30C: [Quality of care] Then comes the abilities related to health and education diseases, because many family are worried as they don’t understand the disease, or if they happen to read some information on the Internet, they will see possible complications, etc. You’ll be more worried, yes, so it may be very important to educate the family on the disease whether it is now or later, on the impact or what will happen may also be quite important. (resident physician, CGU) | M-A-38: Research ability, in this matter, I think, this is not an ability that a pediatrician must have. (attending physician, CGU)F-R-30: Well, I think all of them are important at the moment, but not important to have the ability to do research, and it is difficult to have the credibility of research at the moment. Maybe this is very important to medical center physicians, but I think it is not clinically important at present. (resident physician) | |

| 2. Patient communication | F-A-49: The ability to communicate with doctors and patients, um, when some of our pediatricians communicate, he communicates from his own perspective completely, and the family does not understand it at all. Well, he didn’t care whether his family members could understand him or not, anyway, he just left after speaking like the anchor. Therefore, he actually didn’t care about the anxiety caused by his family members because he couldn’t understand it. That would not work. Well, I have seen this kind of doctor with my own eyes. (attending physician) | F-A-42: It is better to communicate with peer for patients’ related information, because there are other things that are necessary. I will rank other thing first if necessary. (attending physician) |

| F-R-30: In addition, it is a broad and comprehensive knowledge and ability. The main reason is that although I think it may not really be a very specialization, it is because the sentence is comprehensive. It doesn’t necessarily require so much specialization, but in fact, it must be at each contact point. There is a way and most of them are to understand that most of the parents are like they are mastered. Hey, I think about how to explain it. It just doesn’t need to be very specialized, but it’s a little bit of contact for each and every field, that’s like it Is very extensive, but, at least the part that can communicate with family members may have a way to do one with them. Communication, at least we can know what they are talking about, and then we have a better way to pick out some language or something from it, there is a way to explain to the family, and to what extent th”y ca’ understand, hey. (resident physician) | ||

| F-A-36: Then discuss, yes! Because you will need a lot of time for children to discuss with their family, so I think this is very important. (attending physician) | ||

| 3. Empathy | M-A-36: Then comes the abilities related to health and education diseases, because many family are worried because they don’t understand the disease, or if they read some information on the Internet, they will see some possible complications. You’ll be more worried, yes, so it may be very important to educate the family on the disease whether it is now or later, the impact and what will happen may also be quite important. (attending physician) | F-A-49: Well, I don’t think I can ignore the cry of the kid! Yes! If he cries, children’s mother and I can’t continue, and the mother’s attention will be on him. So if there is a cry, we should make a decision, that is, whether to suspend first or what to do. (attending physician) |

| M-A-56: It is because the family members who are engaged in pediatrics care with children patients, but in fact the real dominates is dependent on the family. The kids cannot have their own decision. (attending physician) | ||

| 4. Insight | F-A-44: It is because the family members who are engaged in pediatrics and to face their children patients, but in fact, the family are the real dominates. The pay attention to the patients’ expression even the face and extremities are more important. (attending physician) | F-A-49: The ability to discuss is important because what I know is still limited. I often say that I need to discuss the patient’s condition with my peers, so I can expand my limitations. Of course, the most important thing is to give the patient a correct diagnosis not only alert observation the patients. (attending physician) |

| M-A-56: Because children don’t know how to talk! So sometimes the orders come from family members, but his general posture expression will be able to tell us the overtones. So you should have an extraordinary power of observation to be able to see what his overtones are. Because it is very important, they can’t speak, huh. (attending physician) | ||

| F-A-42: Because I think the pediatrician is less able to talk to the family, the facing of the children patients, so your observation skills are very important. (attending physician) | ||

| F-R-32: I think that keen observation is very important to the pediatrician, that is, you have to be like me in the previous cases of domestic violence, which is what you want to see, which is actually very important to him. (resident physician) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tiao, M.-M.; Chang, Y.-C.; Ou, L.-S.; Hung, C.-F.; Khwepeya, M. An Exploration of Pediatricians’ Professional Identities: A Q-Methodology Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020144

Tiao M-M, Chang Y-C, Ou L-S, Hung C-F, Khwepeya M. An Exploration of Pediatricians’ Professional Identities: A Q-Methodology Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(2):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020144

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiao, Mao-Meng, Yu-Che Chang, Liang-Shiou Ou, Chi-Fa Hung, and Madalitso Khwepeya. 2024. "An Exploration of Pediatricians’ Professional Identities: A Q-Methodology Study" Healthcare 12, no. 2: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020144

APA StyleTiao, M.-M., Chang, Y.-C., Ou, L.-S., Hung, C.-F., & Khwepeya, M. (2024). An Exploration of Pediatricians’ Professional Identities: A Q-Methodology Study. Healthcare, 12(2), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020144